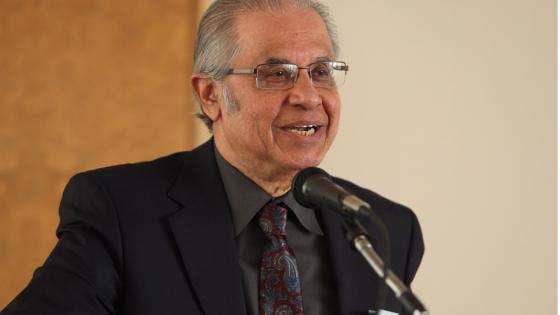

The field of international trade lost one of its giants on 27 September 2022 with the passing of Ron Jones. He played a central role in the development of general equilibrium models of international trade with perfect competition. He was the author of more than 180 articles, and his work appeared in the profession’s most prestigious journals. He received many honours, including being named a fellow of the Econometric Society, a distinguished fellow of the American Economic Association, and a member of the National Academy of Sciences and the American Academy of Arts and Sciences.

Ronald Winthrop Jones was born in Louisville, Kentucky, in 1931. He received a BA from Swarthmore College in 1952 and a PhD from MIT in 1956. After spending a year as an instructor at Swarthmore, he received an offer to join the faculty at the University of Rochester. Lionel McKenzie had been hired to build a PhD programme in economics, and his philosophy was to hire faculty in applied fields with an interest in theory. That approach, combined with the opportunity to teach a graduate course in international trade, led Jones to choose Rochester over Princeton (Jones 2012). He served a brief stint in the army before joining the faculty at Rochester in 1958. Ron was one of McKenzie’s first hires and played a key role in building the department into one of the profession’s top programmes.

Starting with his PhD thesis, Jones made seminal contributions to the central competitive models of international trade: the Ricardian model, the Heckscher-Ohlin model and the specific factor model. For example, the concept of comparative advantage in a two-good, two-country Ricardian model is well known to undergraduate students, but how does that concept extend to a world with many commodities and many countries?

It was known that allocating production on the basis of bilateral comparisons could lead to inefficient outcomes, but a general rule had not been derived. Ron’s 1961 paper in the Review of Economic Studies answered that question by showing that characterising the pattern of efficient specialisations in a many-country, many-commodity world involved minimising the product of the unit labour requirements. He also derived the range of inefficient allocations that could arise in the presence of tariffs.

Ron’s 1965 paper in the Journal of Political Economy laid out an elegant approach to two-sector, two-factor (2x2) models using what would later become known as the ‘hat calculus’ (Jones 1965). He showed how this approach provided a simple way to derive the Stolper-Samuelson and Rybczynski theorems of the Heckscher-Ohlin model, as well as providing insights on economic growth and technological change. He subsequently extended this framework to provide insights on trade models with factor market distortions and Marshallian external economies of scale.

One of the special (and striking) features of the 2x2 model of trade is that it generates what Jones termed a ‘magnification effect’: a change in an exogenous variable (price or factor endowment) has a more than proportional impact on one endogenous variable (factor income or output) and a decline in the other. In the 2x2 model, the identity of the gainer from the magnification effect is the factor intensity of the sector: a price increase in the labour-intensive good benefits labour and harms capital.

A literature subsequently developed to identify the extent to which this magnification effect would generalise to higher dimension models. How does one think about relative factor intensities of sectors in a many-factor, many-good world? Under what conditions will the increase in the price of a good benefit one factor while harming all others?

In generalising the 2x2 model, Jones emphasised the difference between even (nxn) and uneven (mxn) cases. He generated insight into this issue by examining a simple three-factor, two-good model where one of the factors was mobile between sectors and the other two (sector-specific) factors were trapped in their respective sectors.

His 1973 paper (Jones 1973) showed the differential impact of changes in market conditions on mobile factors and specific factors. The magnification effect of price changes on factor incomes applied to the specific factors but not the mobile factors. Similarly, changes in endowments of the specific factors resulted in magnified effects on outputs, whereas changes in the endowment of the mobile factor did not.

The specific factor model has been particularly useful in the literature on the political economy of trade policy, since the fact that the incomes of specific factors are tied to the price of a particular good gives them an interest in organising in order to influence trade policy regarding that good. It also can be interpreted as a short-run version of the Heckscher-Ohlin model, in which labour is mobile in the short run while sector-specific capital only becomes mobile between sectors in the long run.

In subsequent work with Jose Scheinkman (Jones and Scheinkman 1977), Ron examined what can be said about magnification effects in a general m-factor and n-good model. They showed that in the absence of joint production, a good must be a ‘natural friend’ of some factor in the economy, in the sense that raising its price will raise the factor’s return more than proportionally. A good will also be a natural enemy of some factor. But a particular factor does not necessarily have a friend or enemy.

Jones’ work frequently used low dimensional model of international trade to provide insights about the general equilibrium impact of changes in prices, technologies and factor supplies. But as the above examples illustrate, he was also interested in identifying what elements of the low dimensional models generalised to higher dimensions.

Ron was one of the first to focus on the expanding role of global supply chains, a process he referred to as ‘fragmentation’. In a series of papers with Henryk Kierzkowski, beginning in 1990, he emphasised the role of local service links in making it possible for pieces of the production process to be offshored. Jones’ book Globalization and the Theory of Input Trade showed how traditional models of international trade could be expanded to capture the movement of factors of production and the expansion of input trade.

In addition to being a prolific scholar, Jones was a great teacher and expositor. His presentations were clear and insightful, and he always had an elegant way to express an idea. As a result, his graduate international trade class at Rochester was extremely popular, and students were eager to work with him and to seek his advice.

Alan Deardorff’s family tree of trade economists lists 29 students and 119 ‘grandstudents’ of Jones. He was also generous with his time with younger faculty in the profession. His talents also extended to the writing and production of musicals to honour various members of the faculty at Rochester.

Ron was a great advocate for the field of international trade. His textbook World Trade and Payments (with Richard Caves and later Jeffrey Frankel) was one of the leading textbooks in the field, and its popularity is reflected in the fact that it went through ten editions. Ron travelled extensively, giving lectures on his work on international trade, and one would not be surprised to run into him anywhere in the world.

The greater availability of data on international trade and production has led to the ability to quantify trade models with data, and the general equilibrium modelling approach developed by Jones and others has provided building blocks for the development of the field.

References

Caves, R E, J A Frankel, and R W Jones (1990), World Trade and Payments: An Introduction, Scott, Foresman.

Jones, R W (1961), “Comparative advantage and the theory of tariffs: A multi-country, multi-commodity model”, Review of Economic Studies 28(3): 161-75.

Jones, R W (1965), “The structure of simple general equilibrium models”, Journal of Political Economy 73(6): 557-72.

Jones, R W (1971), “A three factor model in theory, trade, and history”, in Bhagwati et al. (eds), Trade, Balance of Payments and Growth, North Holland.

Jones, R W (2000), Globalization and the Theory of Input Trade, Vol. 8, MIT Press.

Jones, R W (2012), “Lionel McKenzie: A recruit's view of the early Rochester days”, International Journal of Economic Theory 8(1): 9-12.

Jones, R W, and H Kierzkowski (1990), “The role of services in production and international trade: A theoretical framework”, in R Jones and A Krueger (eds), The Political Economy of International Trade, Blackwell.

Jones, R W and J A Scheinkman (1977), “The relevance of the two-sector production model in trade theory”, Journal of Political Economy 85(5): 909-35.