In order to avoid the destructive beggar-thy-neighbour strategies that emerged during the Great Depression, the post-war Bretton Woods regime attempted to prevent countries from depreciating their currencies to gain an unfair and sustained competitive advantage. It required fixed, but occasionally adjustable, exchange rates and restricted cross-border capital flows. Elaborate rules for when a country could move its exchange rate peg gave way, in the post-Bretton Woods world of largely flexible exchange rates, to a free-for-all where the only proscribed activity was sustained uni-directional intervention in one’s exchange rate. A widely held view at that time was that each country, doing what was best for itself in a regime of mobile capital, would end up doing what was best for the global equilibrium. For instance, a country trying to unduly depreciate its exchange rate through aggressive monetary policy would see inflation rise to offset any temporary competitive gains. However, even if such automatic adjustment did ever work, the global environment has changed due to (i) weak aggregate demand, in part because of poorly understood consequences of population ageing and productivity slow down; (ii) long-term unemployment; (iii) a more integrated and open world with large capital flows; (iv) significant government and private debt burdens; and (v) sustained low inflation.

The pressure to avoid a consistent breach of the lower inflation bound and the need to restore growth to reduce domestic unemployment could cause a country’s authorities to place more of a burden on unconventional monetary policies, as well as on exchange rate or financial market interventions and repression. These may have large adverse spillover effects on other countries. The domestic mandates of most central banks may not legally allow them to take spillovers into account, and may force them to undertake aggressive policies so long as they have some small positive domestic effect. Consequently, the world may embark on a sub-optimal collective path. We need to re-examine rules of the game for responsible policy in such a context.

Problems with the current system

All monetary policies have external spillover effects. If a country reduces domestic interest rates, its exchange rate also typically depreciates, helping exports. The key, however, is that under normal circumstances, the ‘demand-creating’ effects of lower interest rates on domestic consumption and investment may not be small relative to the ‘demand-switching’ effects of the lower exchange rate in enhancing external demand for the country’s goods. However, this may not be true under abnormal circumstances, e.g. if there is debt overhang, low interest rates might not induce consumers and corporates to spend. Similarly, if capacity utilisation is low, low interest rates may not increase investment.

Other countries can react to the consequences of unconventional monetary policies, and some economists argue that it is their unwillingness to react appropriately that is the fundamental problem (e.g. Bernanke 2015). Yet concerns about monetary and financial stability may prevent those countries, especially less institutionally developed ones, from reacting to offset the disturbance emanating from the initiating country. It seems reasonable that a globally responsible assessment of policies should take the world as it is, rather than as a hypothetical ideal.

If all countries engage in demand switching policies, it can lead to a race to the bottom. Countries may find it hard to get out, requiring a serious appreciation, and a fall in domestic activity.

Principles for setting new rules

If countries agree on a set of new rules or principles, which describe the limits of acceptable behaviour, it can reduce the inefficiencies arising from spillovers, and lead to higher welfare in all the countries. This does not mean that countries have to coordinate policies, only that they have to become better global citizens – provided we can find clear and mutually acceptable rules.

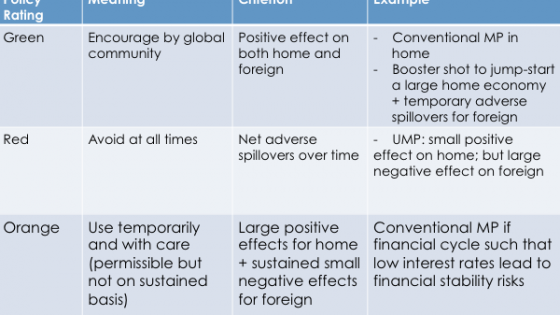

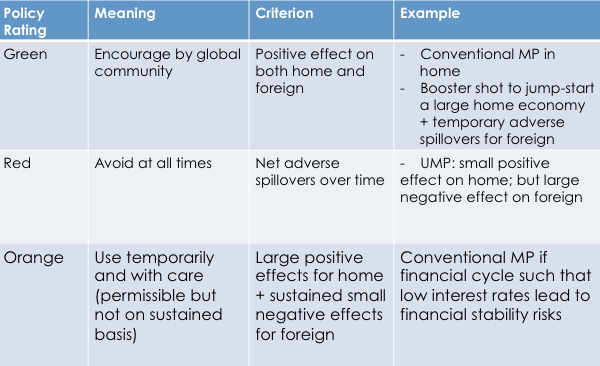

What would be the basis for the new rules? As a start, policies could be broadly rated based on analytical inputs and discussion. To use a driving analogy, polices that have few adverse spillovers, and are even to be encouraged by the global community should be rated green, policies that should be used temporarily and with care could be rated orange, and policies that should be avoided at all times could be rated red. To establish such ratings, the effects of any policy have to be seen over time, rather than at a point in time (Table 1).

Table 1. Principles for setting new rules

At first pass, it may be reasonable to consider some general principles to rate policies:

- Focus on spillover over time. For example, what is red in a static sense may be green in a dynamic sense.

- Foreign countries can respond. Welfare without the policy in question can be compared with welfare after the policy is implemented and response initiated. For example, country A at the zero lower bound initiates quantitative easing (QE). Country B may response by cutting interest rates to avoid capital inflows. The spillover effect could be measured by B’s welfare if QE was not implemented compared to B’s welfare with QE with the policy response in B.

- One could make the argument that economies that are stuck in a rut with few other options should be allowed policies even though they might have adverse spillovers. For example, let us consider the use of unconventional monetary policy in the short term to jump-start an economy? But what if the policy starts getting used in the medium term? Should we carve out exceptions for certain countries? If a stagnant rich country is allowed a free pass, should a historically stagnant, and therefore poor country have a permanent pass to do whatever is in its best interest. It may be difficult to carve out exceptions for rich countries based on relative stagnation without admitting a lot of other exceptions.

- Poor countries have weaker institutions – their central banks have limited credibility, their budgetary frameworks are not constrained by rules and watchdogs, their ability to respond is limited, and they have weaker safety nets. Therefore, there may be a case for weighting spillovers to them more.

- Dollar terms or in utilities. Measuring utilities may be hard, therefore spillovers can be measured in dollar terms.

Overall, whether policies are rated red, green, or orange would depend on a number of factors such as the time dimension; stage of the financial and business cycle in the home and foreign countries; whether the policy action constitutes a booster shot to jump start the economy or gives only a mild boost and has to be employed for a sustained period; whether standard transmission channels are clogged to warrant the use of unconventional policies; whether the foreign country has room to adopt buffering policies; and whether the spillovers impact poor countries which have weak institutions and less room to respond.

State of the literature

Of course, even if we have agreement on broad principles of rating, we need to measure the effects of policies. Unfortunately, the state of the art here is more art than science. Models may reflect the policy biases (unconscious or otherwise) of those devising them, and are at a sufficiently early stage that it would be difficult to draw strong conclusions from them. Perhaps, therefore, more empirical analysis (rather than theoretical models) on the lines of Kamin (2016) (see below) should be emphasised, and seen as an input to a dialogue, with the analysis being refined as we understand actual outcomes better.

How to proceed?

There is much that needs to be pinned down on the international spillovers from domestic policies, especially as regards to the international monetary system. Given the undoubted importance of cross-border trade and capital flows, and the disruptions created by financial market volatility, it does seem an important issue to discuss. Nevertheless, with economic analysis of these issues at an early stage, it is unlikely we will get strong policy prescriptions soon, let alone international agreement on them, especially given that a number of country authorities like central banks have explicit domestic mandates.

We suggest a period of focused discussion, first outside international meetings, then within international meetings. There can be no more important issue to understand and discuss than the international spillovers of domestic policies. Such a discussion need not take place in an environment of finger pointing and defensiveness, but as an attempt to understand what can be reasonable, and not overly intrusive, rules of conduct.

As consensus builds on the rules of conduct, we can contemplate the next step of whether to codify them through international agreement, see how the Articles of multilateral watchdogs like the IMF will have to be altered, and how country authorities will interpret or alter domestic mandates to incorporate international responsibilities.

Author’s note: This article is based on Mishra and Rajan (2016). The views represent those of the authors and not of the Reserve Bank of India, or any of the institutions to which the authors belong.

References

Bernanke, B. S. (2015)., “Federal Reserve Policy in an International Context”, Paper presented at the 16th Jacques Polak Annual Research Conference, IMF, November 5-6, 2015.

Kamin, S. B. (2016), “Cross Border Spillovers from Monetary Policy”, Presentation for the 2016 PBoC-FRBNY Joint Symposium.

Mishra, P. and R. Rajan (2016), “Rules of the Monetary Game”, Reserve Bank of India Working Paper. March 2016.