Editors' note: This column is part of the Vox debate on the economic consequences of war.

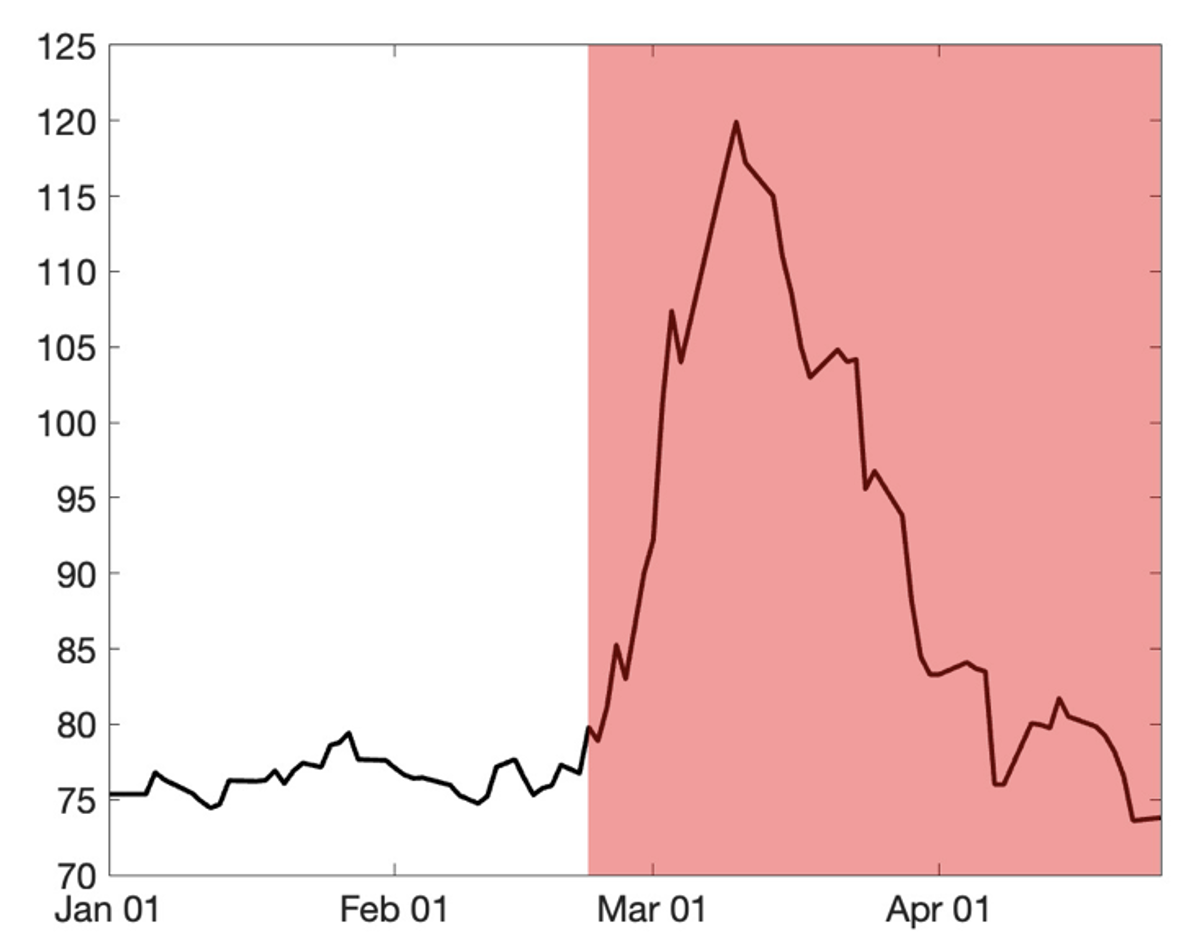

A record number of economic sanctions have been imposed on the Russian economy since the invasion of Ukraine in February 2022. Given that the impact of these restrictions on the real economy will be gradual, observed perhaps only after months or even years, many commentators and policymakers are attempting to infer the effects of sanctions from the short-term dynamics of the ruble exchange rate (see Pestova et al. 2022). In the immediate aftermath of the invasion and the imposition of sanctions, the Russian ruble quickly lost nearly half of its value (Figure 1). However, a few weeks later the value of the ruble started to appreciate and, at the beginning of May, was higher than before the war.

Figure 1 Daily ruble exchange rate (per US dollar) in 2022

These puzzling dynamics lead to several contradictory and misleading interpretations. Some commentators conclude that the imposed sanctions are not working. Similarly, state media in Russia uses the reversion of the exchange rate as an indicator of the resilience of the economy and the short-lived effects of sanctions. Other commentators went to a different extreme, suggesting that given all the policy measures and restrictions imposed to stabilise the exchange rate, it has lost its relevance as an allocative price and has become inconsequential from the perspective of welfare.

Swings in the exchange rate

What explains the puzzling swings in the exchange rate over the last months? To answer this question, we first note that the value of the ruble is determined on the Moscow Exchange, which has become largely disconnected from international financial markets since the beginning of the war. Western sanctions constrain foreign banks from trading rubles and Russian capital controls limit access of Russian residents to foreign markets. As a result, the local supply of foreign currency comes from export revenues and government reserves, while local demand is shaped by import expenditure, foreign liabilities of Russian firms (to the limited extent they exist despite 2014 sanctions), and the use of foreign currency as a store of value. The equilibrium exchange rate equilibrates the local supply and demand of currency and also adjusts to monetary inflation.

In Itskhoki and Mukhin (2022b), we show that a simple equilibrium model of exchange rate determination can explain the ruble dynamics from Figure 1. The overnight freeze of a significant fraction of government foreign reserves, the exclusion of major banks and corporations from international borrowing markets, and a threat of blocking commodity exports led to a sharp depreciation of the ruble on impact. These factors were exacerbated by a sharp increase in the home precautionary demand for foreign currency driven by the rise in inflationary expectations and a collapse in the supply of alternative vehicles for savings.

The exchange rate reversed in mid-March and appreciated gradually over the next month to the pre-war level. First, tougher sanctions on Russia’s imports than on its exports over this period led to a sizable current account surplus and an inflow of foreign currency into the economy (see also Lorenzoni and Werning 2022). Second, with limited access to foreign reserves, the central bank used extensive financial repression, which included strict limits on foreign currency deposit withdrawals, capital outflows, and a 12% tax on local currency conversion to dollars and euros. This constrained the domestic demand for foreign currency. Third, the record-high commodity export revenues allowed the Russian government to enjoy a considerable fiscal surplus, thus far avoiding the need to monetise its fiscal obligations and to induce a monetary-driven depreciation. These three factors are arguably more important in stabilising the exchange rate than conventional monetary tools such as the hike in the policy rate to 20%, which was mostly aimed at stopping a bank run on the ruble deposits and at preventing monetary inflation. Nonetheless, going forward, the prospect of export sanctions and fiscal problems driven by a domestic recession can result in both inflation and devaluation.

Are sanctions failing?

The appreciation of the ruble to the pre-war level has been widely interpreted as a sign that so far sanctions have had a limited effect on the Russian economy. As mentioned above, this argument misses the fact that most restrictions were imposed on Russia’s imports, which lowered demand for foreign currency, thus creating a force for the ruble appreciation. This appreciation, however, cannot offset the increase in the effective costs of imports, particularly in view of their limited availability, or compensate the associated welfare losses and increased real costs of living.

More generally, there is no one-to-one relationship between the exchange rate and welfare, and hence the effectiveness of sanctions cannot be inferred from the exchange rate. On the one hand, sanctions on imports and exports are equivalent in terms of their effect on the consumption of foreign goods — the former increase their relative prices, while the latter lower the amount of resources available to purchase foreign goods — and thus have the same welfare implications. On the other hand, the effect on the exchange rate goes in opposite directions in the two cases — import sanctions decrease the demand for dollars and appreciate the ruble, while export sanctions lower the supply of dollars and depreciate the ruble.

Importantly, the equivalence extends to fiscal revenues: although import restrictions have no direct effect on government income, the associated change in the exchange rate lowers nominal and real fiscal revenues in the same way as export restrictions (Amiti et al. 2017). The fact that exports constitute an important source of government revenues does not change the result and thus cannot be used as an argument in favour of export over import sanctions. Instead, the use of export restrictions can be justified if import sanctions are considered insufficient, are limited by the trade share of sanctioning countries, or minimise the costs to sanctioning countries (Sturm 2022).

Is the exchange rate irrelevant?

Equally misleading is the common view that the policy restrictions make the exchange rate irrelevant for the economy. Despite the large interventions of the government in the foreign exchange market, including multiple restrictions on purchasing and managing foreign currency, the value of the ruble affects the economy via two channels. First, the appreciation of the exchange rate increases the purchasing power of households and boosts consumption of foreign goods mitigating the negative effects of import sanctions. Importantly, this comes at the expense of the households that want to hold foreign currency as a safe asset and thus are subject to the measures of financial repression that are used to strengthen the ruble. In other words, the policy of financial repression creates redistributive effects from savers (who tend to be richer households) to consumers of foreign goods (many of whom are poorer ‘hand-to-mouth’ households).

Second, the nominal exchange rate is a signal about monetary policy, which is especially valuable in an environment with high uncertainty and low trust in policymakers. Budget deficit pushes the government to monetise its nominal liabilities. Even before this happens, uncertainty about the monetary policy can lower demand for local currency deposits, leading to higher inflation and a run on the banks. To regain credibility, anchor inflation expectations, and stabilise the financial system, the central bank can adopt a nominal peg to communicate its policy priorities (Athey et al. 2005, Itskhoki and Mukhin 2022a).

In sum, a strong appreciation of the ruble over the last two months was driven by import sanctions and the financial repression, both of which lowered demand for foreign currency. This does not mean that the sanctions are not working - in fact, there is an important equivalence between import and export restrictions in terms of welfare effects and government fiscal losses. Stabilising the exchange rate allows the Russian government to anchor inflation expectations and support consumption but comes at the cost of financial repression of domestic savers.

References

Amiti, M, E Farhi, G Gopinath and O Itskhoki (2017), “The border adjustment tax”, VoxEU.org, 19 June.

Athey, S, A Atkeson and P J Kehoe (2005), “The optimal degree of discretion in monetary policy”, Econometrica 73(5): 1431–1475.

Itskhoki, O and D Mukhin (2022a), “The Mussa puzzle and the optimal exchange rate policy”, VoxEU.org, 17 January.

Itskhoki, O and D Mukhin (2022b), “Sanctions and the Exchange Rate”, NBER Working Paper No 30009.

Lorenzoni, G and I Werning (2022), “A Minimalist Model for the Ruble During the Russian Invasion of Ukraine”, NBER Working Paper No. 29929.

Pestova, A, M Mamonov and S Ongena (2022), “The price of war: Macroeconomic effects of the 2022 sanctions on Russia”, VoxEU.org, 15 April.

Sturm, J (2022), “The simple economics of a tariff on Russian energy imports”, VoxEU.org, 13 April.