Traditionally, services have not been thought to hold much promise for driving development. The simultaneity of production and consumption and limited opportunities for machinery to augment labour precluded scale economies in the provision of services. In contrast, the manufacturing-led model was characterised by scale economies based on the production of tradable goods in large plants where capital embedded in machinery allows workers to be productive. Today, the services sector employs half of workers in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs), and these shares have been steadily growing. If these jobs do not have the same productivity potential, it is understandable that ‘premature de-industrialisation’ (Rodrik 2016) is seen as worrisome.

This narrative is starting to change. On the one hand, the diffusion of labour-saving technologies has significantly reduced the potential of manufacturing industries to absorb low-skill workers (Rodrik 2021). On the other hand, new evidence suggests that productivity growth underlies the expansion of the services sector in developing economies, such as India, where most jobs have been created since the 1990s (Fan et al. 2021). In a new book (Nayyar et al. 2021), we use census and administrative data covering more than 10 million firms across 20 LMICs, supplemented with aggregated statistical data from high-income countries (HICs), to examine the productivity and job creating potential of services firms. We establish several stylised facts underscoring that the services sector deserves more attention for the contributions its firms can make. People may picture large factories as a model of success, but more than size it is productivity that matters. And here, many services firms perform well.

Services establishments are small and have lower growth

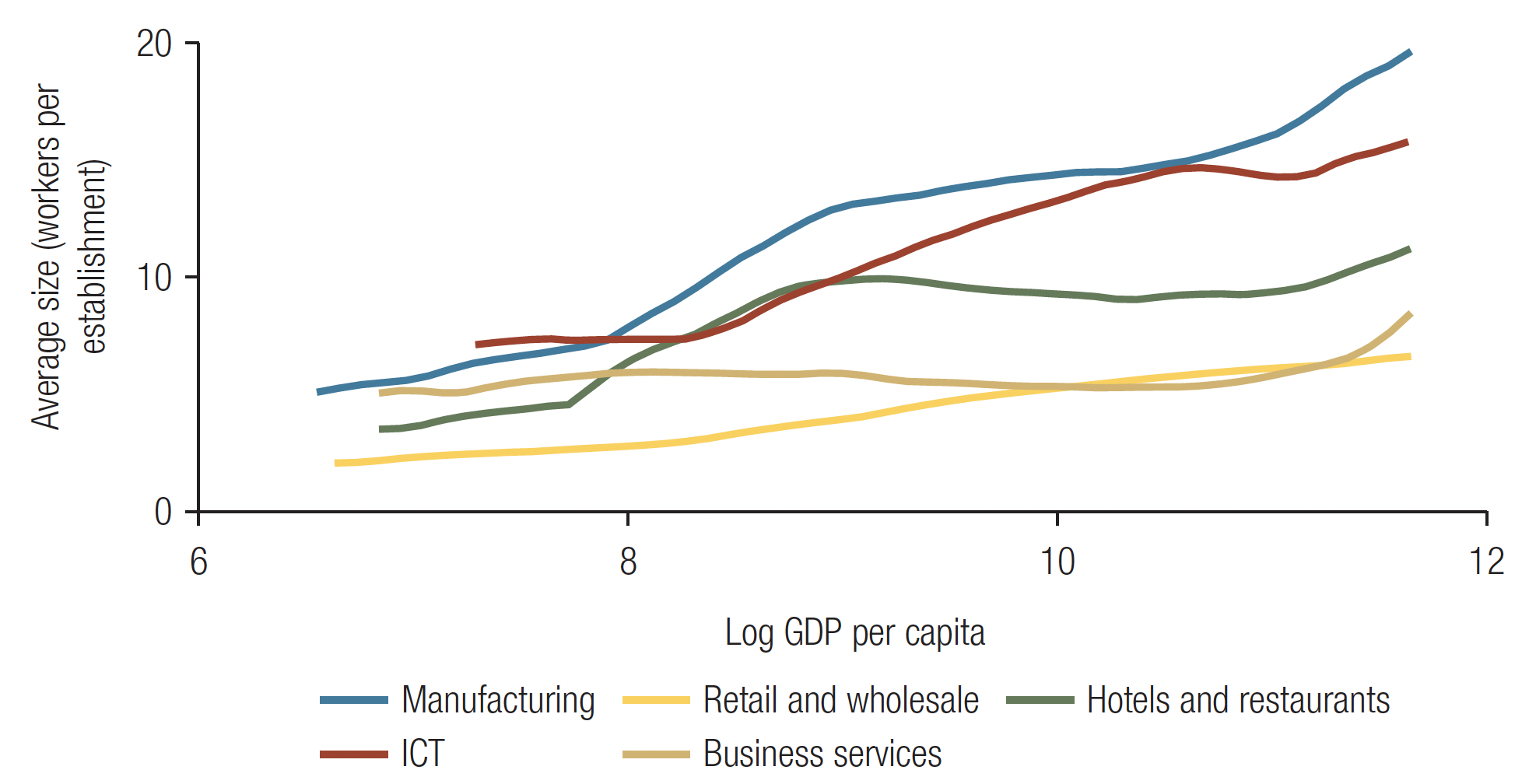

Services establishments tend to be smaller, on average, than manufacturing firms. In LMICs the average service establishment employs only three workers, compared with 11 workers in the average manufacturing establishment. The establishment size of firms in lower-skill services, such as retail, is particularly small (see Figure 1) and may be attributable to the presence of a large informal sector.

Figure 1 Comparing the average size of manufacturing with services

Average establishment size, average of latest available years, 2000-12

Source: Nayyar et al. (2021)

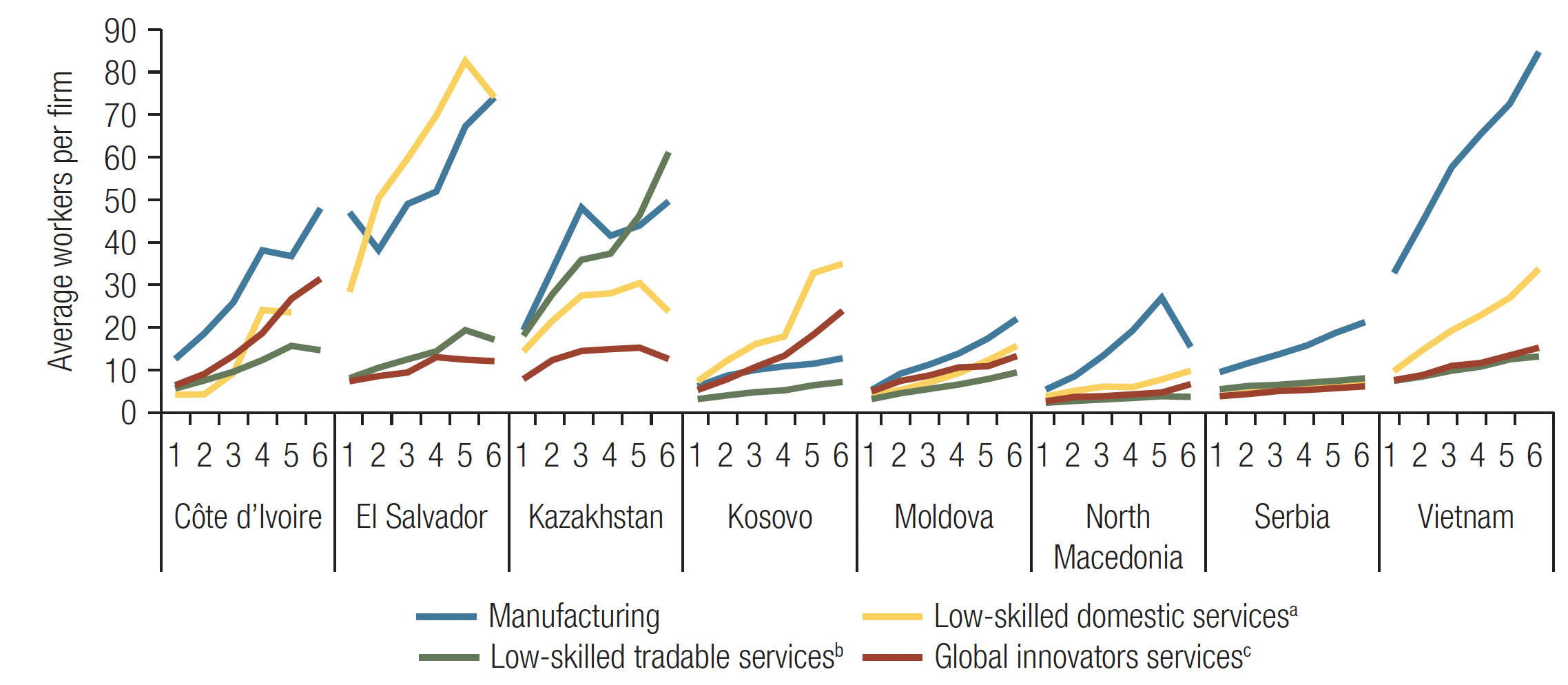

Services firms are also less likely to grow over their lifetimes (Figure 2). In the group of countries with suitable panel data, we see that a manufacturing firm triples in size over their first six years (growing by 26 employees on average), compared to only a doubling in services (growing by only three employees). This pattern can be seen across different services subsectors, regardless of whether they are relying on low or high levels of skill or are tradable, although some country differences remain.

Figure 2 Employment growth during an establishment’s initial six years tends to be lower in services

Average number of employees in selected LMICs, available years 2003-17

Source: Nayyar et al. (2021).

Note: Low-skilled domestic services include retail, personal services, and entertainment; low-skilled tradeables include food and accommodation, wholesale, and transportation services; global innovator services include Information and Communications Technology (ICT), finance, and professional services.

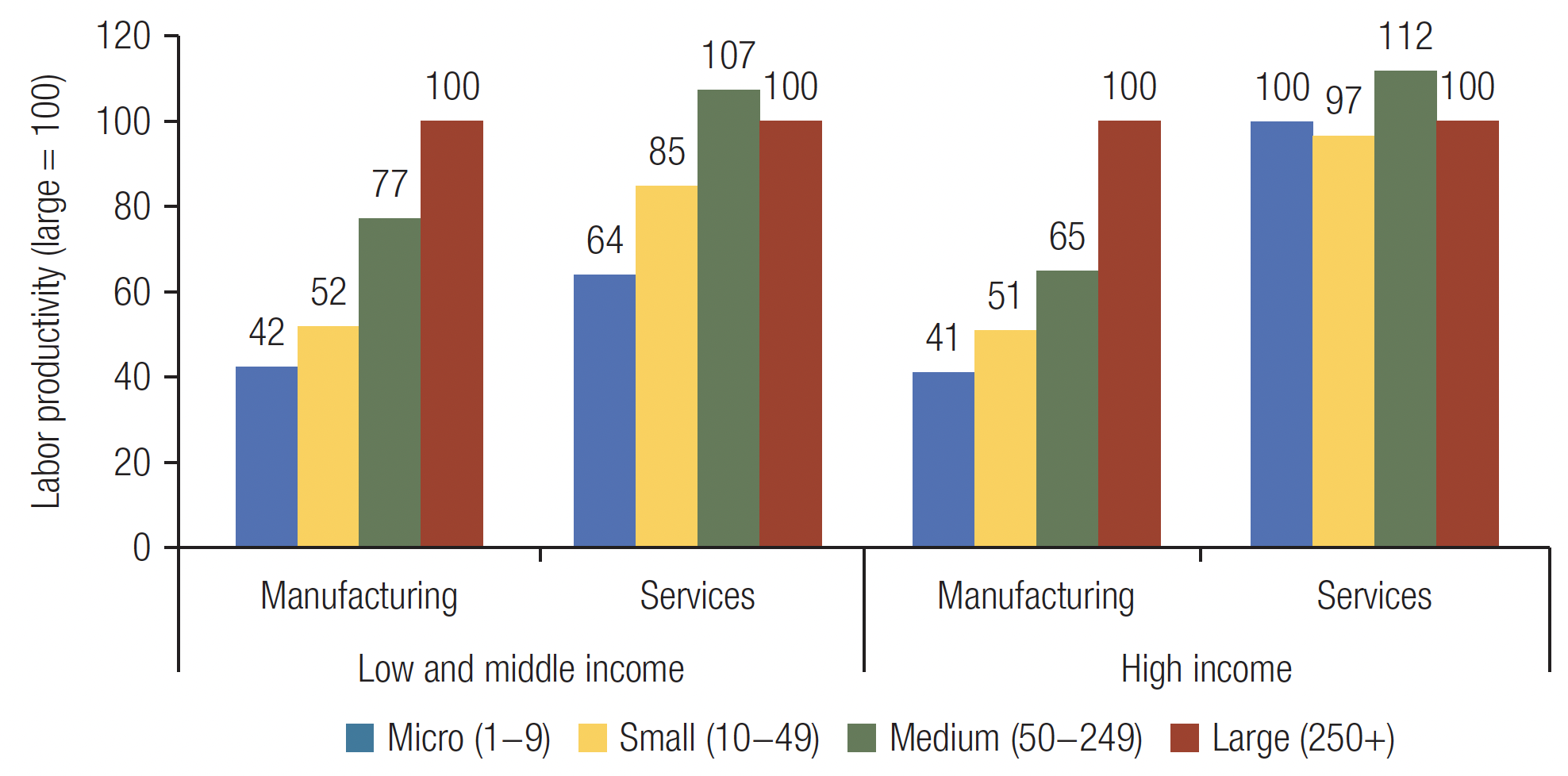

But this matters less for productivity than expected

The small size of services establishments does not preclude them from being productive. In high-income countries, a small services firm can just be as productive as a large firm (Figure 3). This stands at a stark contrast to manufacturing firms, where productivity is strongly correlated with size. The result corroborates earlier findings from OECD countries (Berlingieri et al. 2018). In LMICs, the relationship between size and productivity is weaker for services firms compared to manufacturing firms, albeit not as weak as in high-income countries.

Figure 3 Especially in high-income countries, small services firms are just as productive as larger ones

Labour productivity relative to large firms, latest available year, 2010-17

Source: Nayyar et al. (2021), based on data from 20 LMICs, supplemented with OECD/Eurostat Structural Business Survey data.

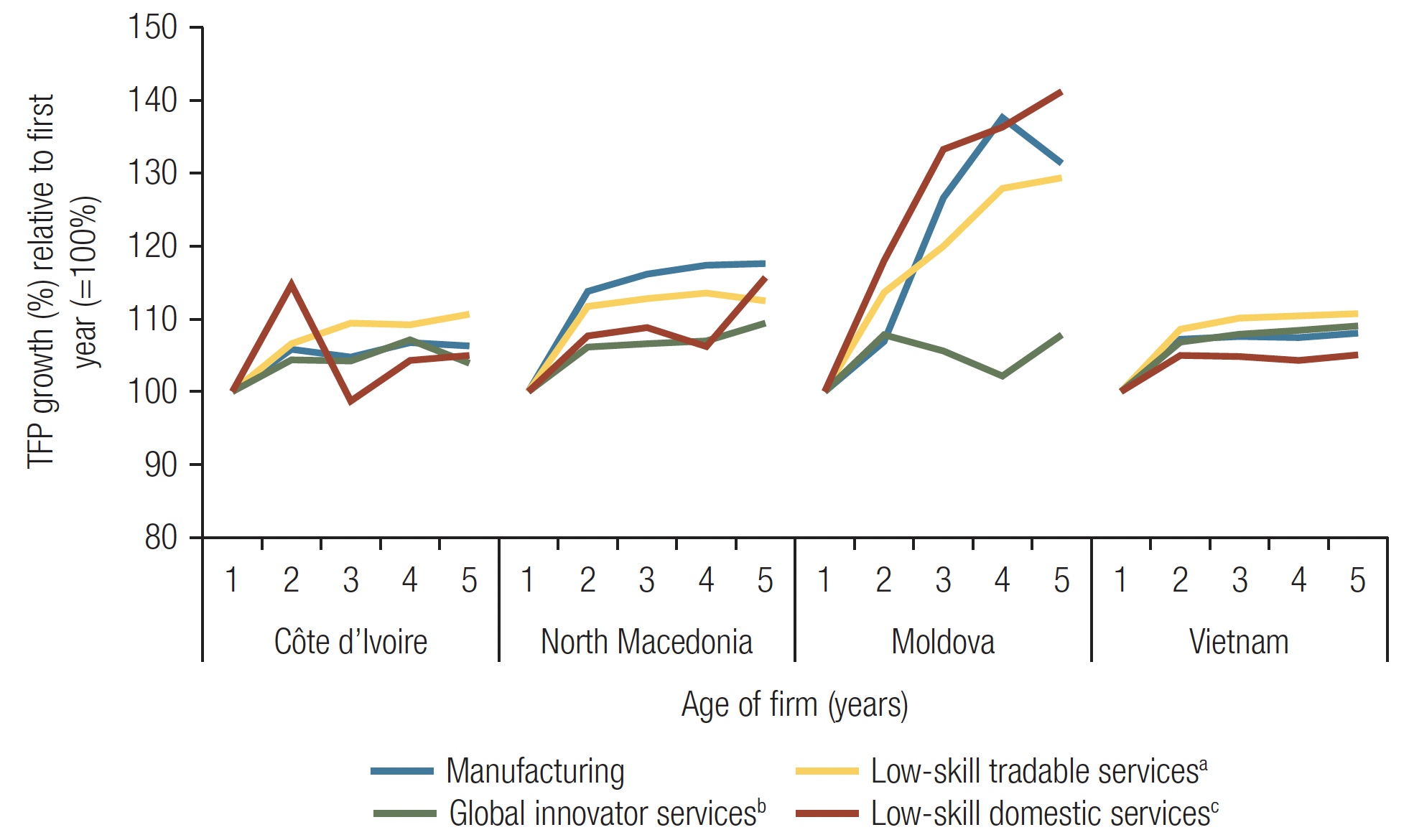

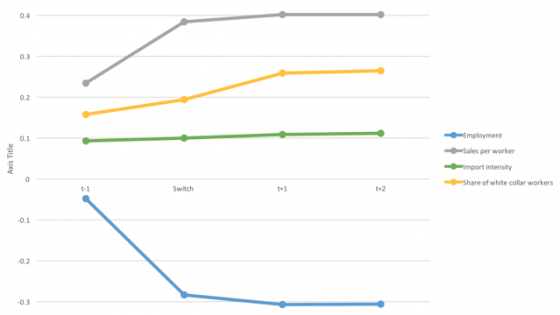

Furthermore, the lack of growth in terms of employment does not mean that services cannot become more productive over their lifetimes. A similar analysis of firm entrants, but now on productivity instead of size, shows that the productivity growth is very similar to that of manufacturing firms in their first five years (Figure 4). So, while services firms do not get large in this period, they still become more productive.

Figure 4 The productivity growth of services firms in their first five years often matches that of manufacturing firms

TFP growth of services and manufacturing firms in four LMICs, by sector or sector group, available years, 2003–17

Source: Nayyar et al. (2021).

Note: see Figure 2 for the definitions of service sector groupings.

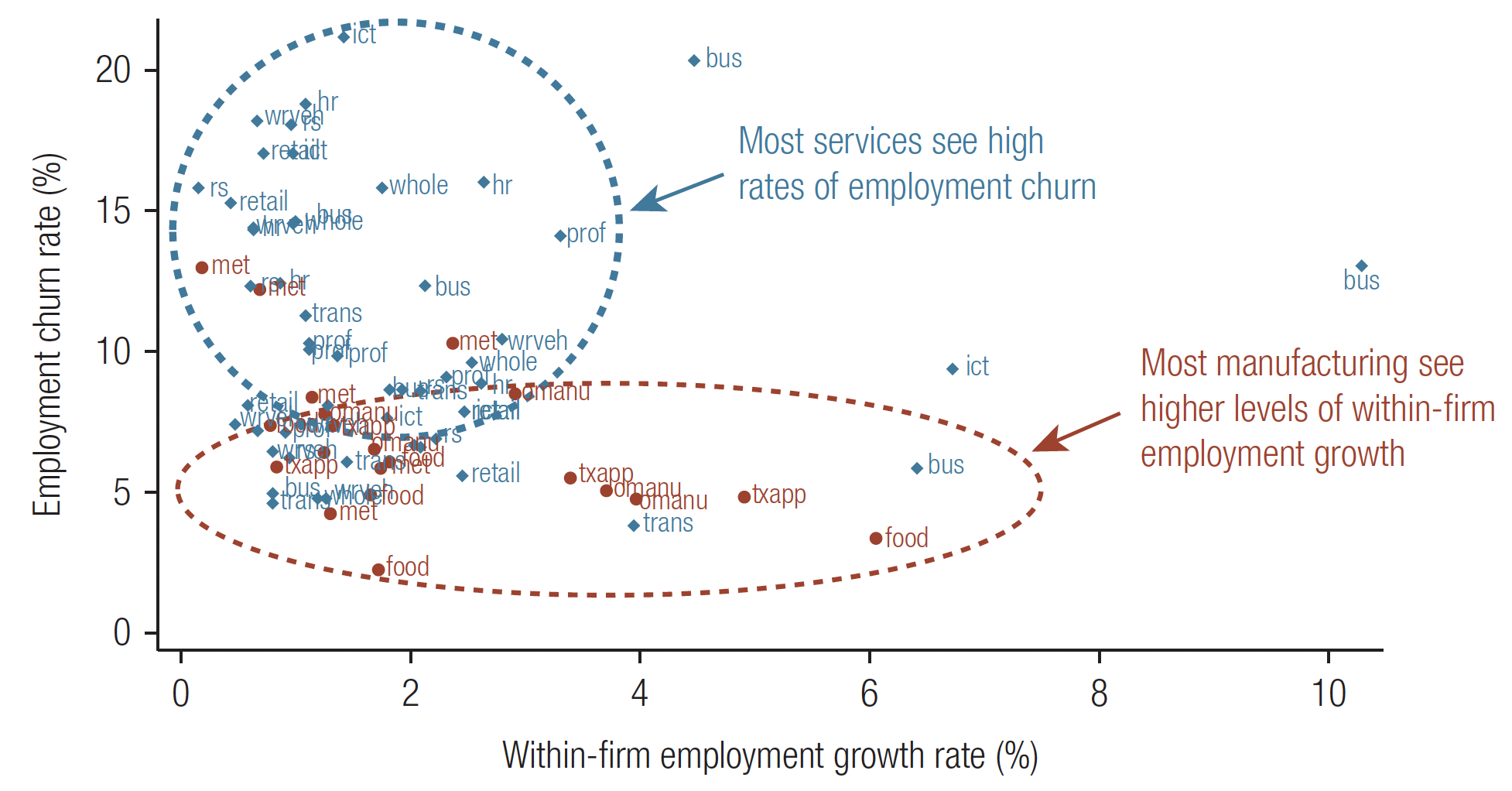

The employment dynamism of the services sector is manifested through market ‘churn’ rather than firm growth. Services workers are much more likely than manufacturing workers to be in a firm that has just been entered or is about to exit. For example, in Cambodia one in five services workers was in a business that was established less than a year ago. This is in line with findings from the US, where close to 20% of workers in services were employed in a firm younger than five years, compared with about 7% of workers in manufacturing (Decker et al. 2014). Young, and often small, firms are therefore crucial for the performance of the services sector.

Figure 5 Among services firms, employment changes are driven more by entry and exit than by firm growth

Employment changes during firms’ first five years and the employment churn rate, latest available year, 2010–17

Source: Nayyar et al. (2021), based on data from six LMICs with suitable panel data.

Scaling up – but not sizing up – through intangible and human capital

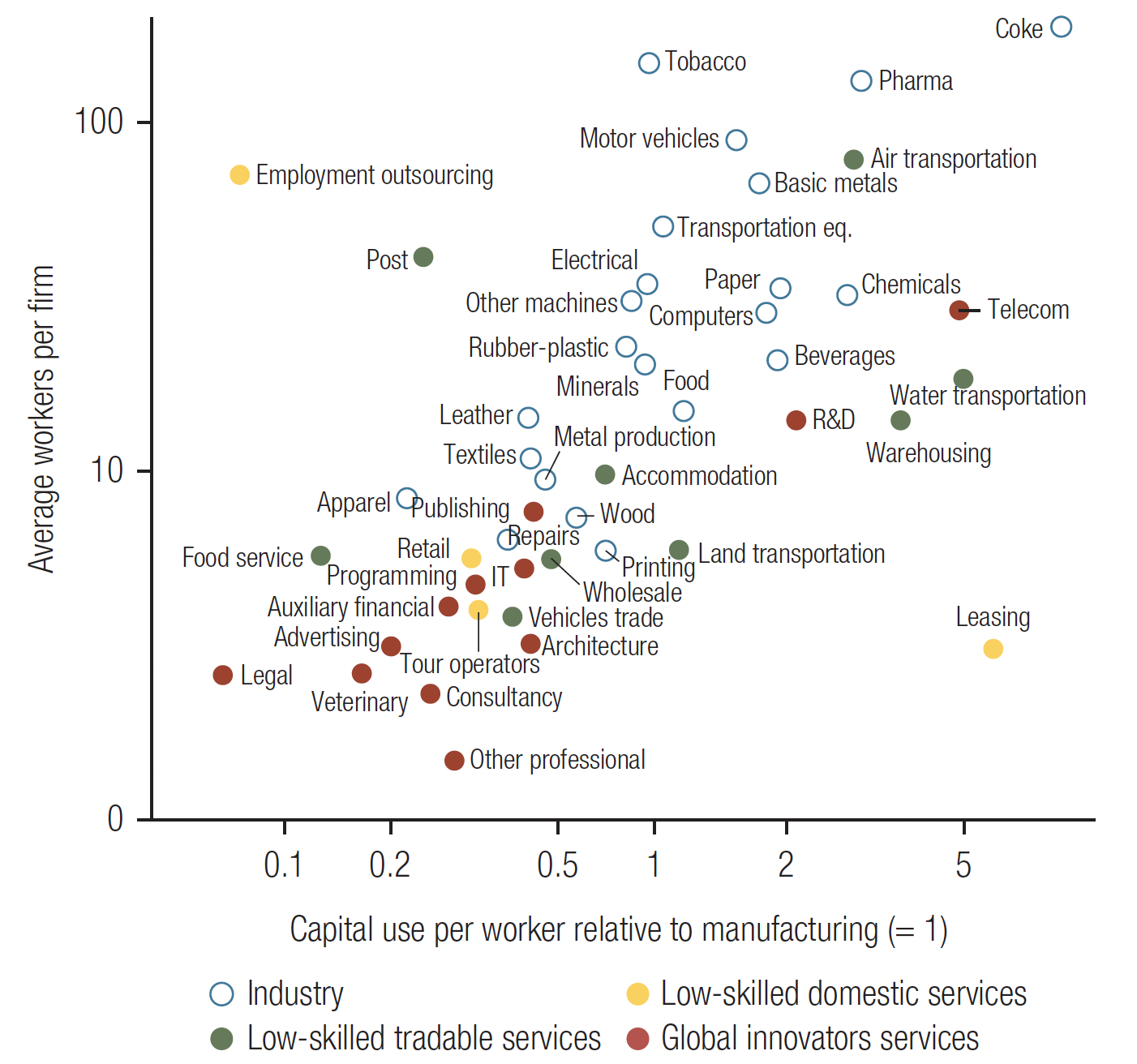

A key factor driving the differences observed in scale between manufacturing and services establishments is the role of capital. Most services sectors are much less intensive in the use of machinery and other physical capital compared to manufacturing, with a few notable exceptions such as transportation, warehousing, and telecommunications. This has implications for size and growth. Cross-sectoral data from OECD countries suggests that industries that are less capital-intensive also tend to have a smaller average firm size (Figure 6).

Figure 6 Lower capital-intensity is associated with smaller average firm size

Source: Nayyar et al. (2021), based on OECD STAN and SBS data.

This raises the question of how services firms can be scaled up if it is not ‘sizing up’ in the traditional sense. At the extensive margin, services firms can achieve scale in setting up multiple establishments, for example through branching or franchising, sharing valuable intangible capital such as organisational know-how, brand value and intellectual property. The diffusion of digital technologies has greatly expanded the potential here. Investments in ICT and the related intangible capital such as data analytics and management practices help standardize optimal staffing, daily food purchases, and the introduction of new menu items in restaurants, enabling them to replicate the same production process in multiple locations near consumers (Hsieh and Rossi-Hansberg 2020).

Digital platforms are another example of achieving scale without necessarily increasing the size of the firm by relying on many individual providers. Take the example of highly skilled online freelancers for computer programming and other professional services in developing economies who can reach multiple customers located far away, limiting the ‘proximity burden’ traditionally associated with services (Baldwin 2019). Such telemigration has only increased with the COVID-19 pandemic (Baldwin and Forslid 2020).

Opportunities for productivity growth at the intensive margin too should not be discounted. Deepening human capital and other more intangible forms of capital can raise quality and productivity, without increasing the number of workers in the same firm. Increasingly, therefore, service establishments can achieve greater scale economies and higher productivity without increasing size. In services, small can be beautiful.

References

Baldwin, R (2019), The globotics upheaval: Globalization, robotics and the future of work, Oxford University Press.

Baldwin, R and R Forslid (2020), “Covid 19, globotics, and development”, VoxEU.org, 16 July.

Berlingieri, G, S Calligaris, and C Criscuolo (2018), “The productivity-wage premium: Does size still matter in a service economy?”, AEA Papers and Proceedings 108: 328-33 (see also the Vox column here).

Decker, R, J Haltiwanger, R Jarmin, and J Miranda (2014), “The role of entrepreneurship in US job creation and economic dynamism”, Journal of Economic Perspectives 28 (3): 3–24.

Fan, T, M Peters, and F Zilibotti (2021), “Service-led or service-biased growth? Equilibrium development accounting across Indian districts”, NBER working paper 28551.

Hsieh, C-T and E Rossi-Hansberg (2020), “The industrial revolution in services”, NBER working paper 25968, National Bureau of Economic Research, Cambridge: Massachusetts.

Nayyar, G, M Hallward-Driemeier, and E Davies (2021), At your service? The promise of services-led development, The World Bank.

Rodrik, D (2016), “Premature deindustrialization”, Journal of Economic Growth 21 (1): 1–33 (see also the Vox column here).

Rodrik, D (2021), “The metamorphosis of growth policy”, Project Syndicate, 11 October.