For services trade negotiations, comprehensive information on trade in services by mode of supply has been a longstanding priority for many governments as part of their multilateral or regional trade negotiations (see for instance DFAT 2007:5). The US Bureau of Economic Analysis has been at the forefront of detailed services trade statistics for many years, including on issues pertaining to modes of supply.[1] Meehan (2014) offers an assessment of New Zealand's services exports by modes of supply based on balance of payment data (modes 1, 2, and 4). The Reserve Bank of India also conducts an annual survey of computer software and IT enabled services exports that includes a split by modes of supply.

Services by modes of supply: A long overdue policy priority

Although the need for better services trade statistics to inform services trade negotiations was clearly identified early on (e.g. Karsenty 2000, Chang et al. 1999), the growing economic importance of services trade is still not matched by the level of statistical details needed by policymakers. Notable exceptions are the efforts to produce services by modes of supply estimates by Karsenty (2000), Maurer et al. (2008), Magdelaine and Maurer (2008), and the WTO (2016).

In parallel, a large body of literature was concerned with a whole range of other key services issues such as mapping and quantifying the various trade restrictions affecting services trade (e.g. the longstanding work programme carried out by the OECD and World Bank on services restrictiveness indexes), assessing the nature of services commitments in various trade agreements. For instance, based on the World Bank Services Trade Restrictions database, countries vary widely in the level of their cross-sectoral restrictiveness index across modes. An even greater degree of variation is found when breaking down services trade restrictions by country, sector, and mode of supply.

A similar effort to chart the landscape of trade restrictions faced by services trade in a wide range of countries and sectors has been carried out over the years by the OECD Secretariat, leading to a rich database and a Services Trade Restrictiveness Index.

Despite these major analytical advances, the current services trade statistics and the analytical tools available are not well equipped to capture all the negotiating parameters. In the absence of such data, the task of trade negotiators is made more difficult. There is a lot at stake if trade negotiations are delayed or lead to a suboptimal outcome. To put things into perspective, the overall EU trade policy agenda has the potential to deliver up to 2% additional growth to the EU economy (European Commission 2013). A big chunk of this will come from successful services negotiations as part of EU free trade agreements. Optimising the 2% long-term additional growth potential stemming from the current EU trade negotiating agenda by speeding up the overall negotiating process and ensuring a better liberalisation outcome in the area of services therefore seems a pressing policy priority.

Beyond the EU agenda, given the growing importance of services for many developing countries, it would be extremely important to ensure an optimal negotiating outcome at global level. Having a services trade dataset by modes of supply will not only improve the negotiating process, but also other critical trade policy priorities, such as monitoring and implementation of existing trade agreements, ex post evaluations, and so on. Providing clear evidence not only that trade agreements work well in terms of boosting trade in goods from tariff removal but that they are also beneficial for services companies and their customers is of paramount importance, at a time where many sceptical voices call into question the benefits of trade liberalisation.

EU services by modes of supply: A new Eurostat initiative

Given the policy relevance of improved service statistics, Eurostat has launched a project to estimate services trade flows by modes of supply, using the existing UN methodological guidelines and the available balance of payments (BoP) and foreign affiliates trade statistics (FATS) for 2013 between the EU and the rest of the world. Rueda et al. (2016) offer a comprehensive description of the Eurostat methodology and data sources.

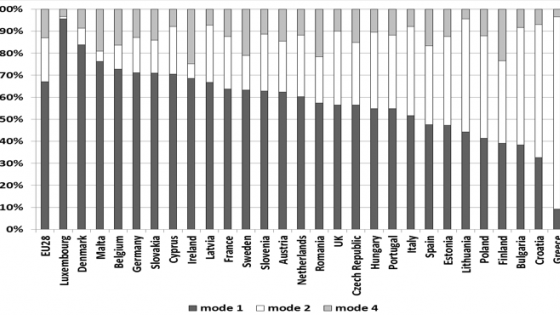

One of the key messages confirmed by the new Eurostat database is the overwhelming importance of mode 3 (commercial presence) for EU services trade (Figure 1). Since mode 3 services statistics are not included in the standard BoP services trade data, the size of EU services trade has been so far severely underestimated. In fact, when mode 3 services are included, EU services trade becomes three times larger than previously reported.

Figure 1 EU total services exports by modes of supply

Note: Mode 1 is cross-border supply, Mode 2 consumption abroad, Mode 3 commercial presence, and Mode 4 is the presence of natural persons.

Source: Rueda et al. (2016).

As shown in Figure 1, our results on the EU total services exports by mode of supply indicate that mode 3 is the largest mode of service delivery abroad (69% of the total), followed by mode 1and mode 2 services. These EU estimates are in line with the other services modes of supply at global level and obtained for other trading partners (e.g. the US, Australia).

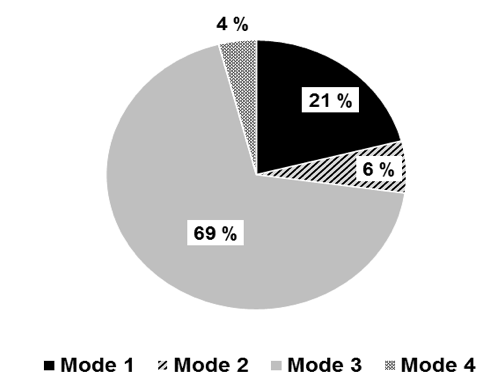

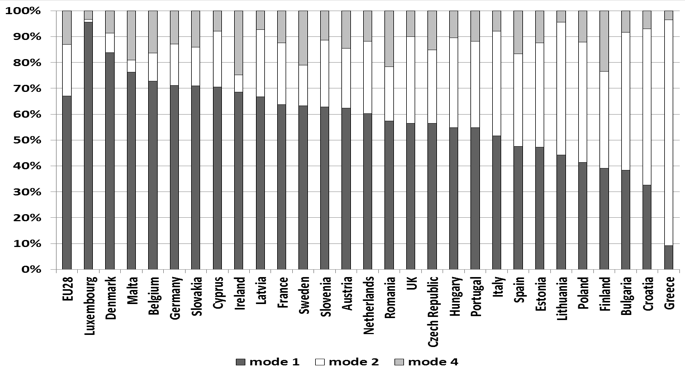

Figure 2 EU28 services exports by modes of supply

Note: Mode 3 data not included, due to methodological limitations.

Source: Rueda et al. (2016).

However, although at the EU level the results are similar to previous global estimates, a second important finding by Eurostat is the considerable variation across EU member states in terms of the importance of the various modes of supply (Figure 2). Disregarding mode 3, for which methodological limitations still exist, we notice that countries like Luxembourg and Denmark rely to a very large extent on mode 1. In contrast, Greece, Croatia and Bulgaria export a great deal under mode 2, whereas Ireland, Finland and Romania had the highest shares among EU countries in terms of mode 4 services exports.

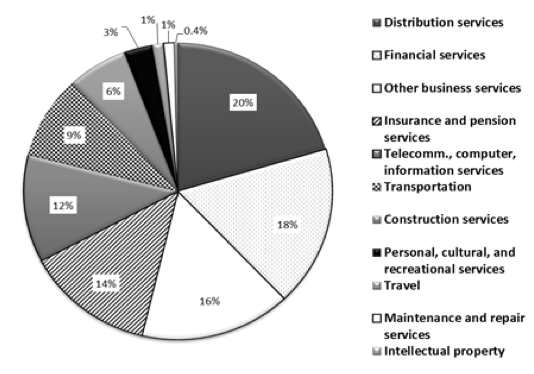

A further breakdown of EU mode 3 exports indicates that more than two thirds of the total value of EU services exports supplied under mode 3 were associated to distribution services, other business services, and financial and insurance services (Figure 3). Telecommunication and information services, as well as transport activities follow in order of importance.

Figure 3 EU28 mode 3 services exports: Sectoral breakdown

Source: Rueda et al. (2016).

Towards a global services dataset by modes of supply: Next steps

The academic community and trade negotiators need a global services trade dataset by modes of supply to formulate their trade negotiating strategies and respond to their analytical questions. To support the process of creating a global database in trade in services with modes of supply for future use in trade negotiations, the European Commission has launched a new initiative, in cooperation with the WTO, other interested institutional partners (OECD, UN agencies), and the research community (the GTAP community, input-output experts, national statisticians, etc.). When modes of supply will be part of the analytical toolbox available to policymakers, trade negotiators will be finally equipped with a state-of-the-art analytical platform that can guide them towards a more optimal outcome of bilateral, plurilateral or multilateral services negotiations.

Author’s note: This column is based on a longer version published as part of DG TRADE Chief Economist Notes series. The views expressed therein are those of the author and do not necessarily represent the views of the European Commission.

References

Baldwin, R and F Kimura (1998) “Measuring U.S. International Goods and Services Transactions", NBER Working Paper No. 5516, National Bureau of Economic Research: Cambridge.

Borchert, I, B Gootiiz and A Mattoo (2012) "Guide to the Services Trade Restrictions Database", World Bank Policy Research Working Paper no. 6108, The World Bank: Washington, DC.

Chang, P, G Karsenty, A Mattoo, and J Richtering (1999) "GATS, the Modes of Supply and Statistics on Trade in Services", Journal of World Trade 33(3): 93-115.

DFAT (2007) "Trade in services statistics – the Australian experience", Australian Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade.

European Commission (2013) Trade, Growth and Jobs: Commission contribution to the European Council, European Commission: Brussels, February.

Karsenty, G (2000) "Assessing Trade in Services by Modes of Supply", in P Sauvé and R M Stern (eds.), GATS 2000: New Directions in Services Trade Liberalization, Washington, DC: Brookings Institution Press, pp. 33-56.

Maurer, A, Y Marcus, J Magdeleine, and B d’Andrea (2008) "Measuring Trade in Services" in A Mattoo, R M Stern and G Zanini (eds.) (2008) A Handbook of International Trade in Services, Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Magdeleine, J and A Maurer (2008) "Measuring GATS Mode 4 Trade Flows", WTO Staff Working Paper 5/2008, Geneva.

Meehan, L (2014) "New Zealand's international trade in services: A background note", Research Note 1/2014, New Zealand Productivity Commission.

Rueda-Cantuche, J M, R Kerner, L Cernat and V Ritola (2016) “Trade in services by GATS modes of supply: Statistical concepts and first EU estimates”, DG Trade Chief Economist Note No. 3/2016, November.

Endnotes

[1] For an early attempt to offer a comprehensive assessment of US services trade from balance of payment and foreign affiliates trade in services, see Baldwin and Kimura (1998).