The gloom and doom about goods trade has obscured the quiet resilience of services trade. Services account for over one-fifth of global cross-border trade; for countries such as India and the US, it is close to one-third of all exports. Data on cross-border trade from the US reveals that since mid-2008, trade in goods declined drastically but trade in some services held up remarkably well.1 More aggregate data available for other OECD countries also suggests that services trade suffered less from the crisis than goods trade.

Within services, trade in goods-related transport services and crisis-related financial services shrank, as did expenditure on tourism abroad. But trade in a range of business, professional, and technical services remained largely unscathed. Hence, developing countries like India, which are relatively specialised in business process outsourcing and information technology services, suffered much smaller declines in total exports to the US than countries like Brazil or regions like Africa which are specialised in exports of goods, transport services, or tourism services.

US services imports and exports

In what follows, we focus mainly on the markedly different behaviour of goods and services trade flows between the onset of the crisis and the point in time when the impact of the crisis seemed to have bottomed out. (See Borchert and Mattoo 2009 for a broader analysis.)

Both goods and services trade peaked in July 2008, after which both declined until the trough was reached in May 2009.2 While monthly US imports of goods fell by nearly 40%, service imports fell by 17%. Similarly, while US monthly US goods exports declined by 32%, its services exports declined by 15%.3

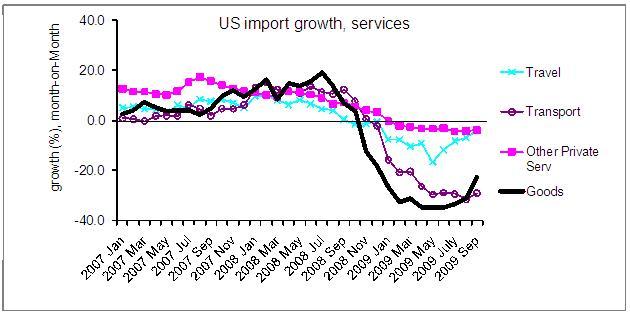

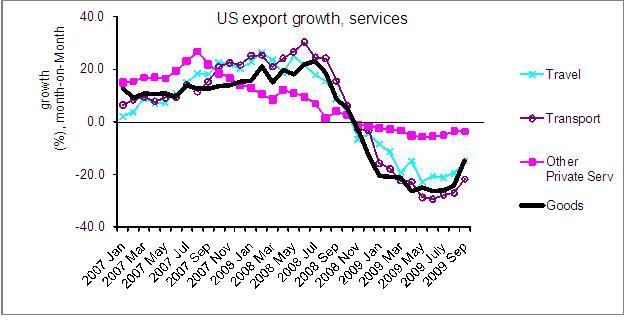

Within services trade, interesting patterns emerge (Figures 1 and 2):

- The value of imports and exports of goods-related services such as international transport shrank by 39% (on an annual basis) between peak and trough, very much in line with goods trade as one would expect.

- Expenditure on US tourism abroad (a US import of services) and foreign tourists in the US (a US service export) contracted as well by 18%, and 29% respectively.

- Trade in ‘Other Private Services’ – mainly business services, declined by only 7% on both the import and export sides.

Figure 1 Year-on-year growth rates of US monthly imports of goods and services, January 2007 – September 2009

Source: BEA, US International Trade in Goods and Services, months seasonally adjusted.

Figure 2 Year-on-year growth rates of US monthly exports of goods and services, January 2007 – September 2009

Source: BEA, US International Trade in Goods and Services, months seasonally adjusted.

There are contrasting trends within ‘Other Private Services’. On the one hand, trade in financial services contracted sharply in the first quarter of 2009 (year-on-year imports by 32% and exports by 17%). On the other hand, trade in a range of other services continued to grow, with US exports growing even faster than US imports. This pattern is evident in insurance (imports by 12%, exports by 19%) and in a range of business, professional and technical services (imports were virtually unchanged while exports grew by 2%).

Trade of other OECD countries

The US accounts for 17% of all OECD imports of services and 20% of all OECD exports of services. How far does its experience reflect that of the OECD countries more generally?

Trade data covering the first quarter of 2009 shows that services trade flows were also more robust across a number of OECD countries, although this data is only available for services trade as a whole and not for its subcomponents.

Figure 3 compares changes in goods and services trade. The chart displays data for OECD nations plus Brazil, Indonesia, India, Russia, and South Africa. For each country, the annual growth rate during the crisis of goods imports is plotted on the vertical axis while the growth in services imports is plotted on the horizontal axis. Both rates are negative for all countries but, interestingly, imports of goods are contracting faster for all countries except for Norway and India (these are just slightly above the 45 degree line).

Until more detailed data becomes available, we can only conclude that evidence from other OECD countries does not contradict the picture of the relative resilience of services trade emerging from US data.

Figure 3 Growth of goods and services imports of 29 OECD and 2 non-OECD countries, annual growth rates, 2009-Q1.

Source: OECD, Balance of Payments Statistics, Trade in Services by Partner Country, millions of dollars, seasonally adjusted. Iceland has been dropped.

The impact on developing countries

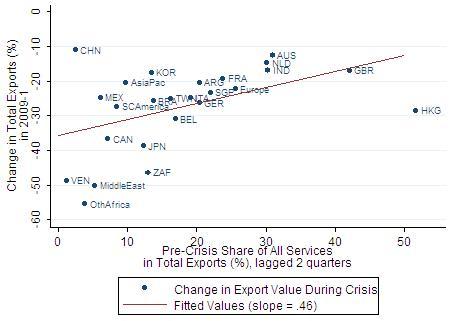

Overall exports to the US from developing-countries that are specialised in services, like India (31% share of services in total exports), declined less than exports of countries and regions for which services are less important, such as Brazil (14% share) and Africa (4% share, excluding South Africa, the share of which is 13%).

Figure 4 makes the point. The contractions in their total exports (goods and services) to the US in the first quarter 2009 were:

- India (17%),

- Brazil (26%),

- Africa (55%; South Africa: 46%).

- China is an exception to this pattern as the share of services in its exports to the US is rather low (2.5%) yet its overall exports declined by only 11%.

Figure 4 Change in the value and growth rates of exports to the US and share of services in exports, selected countries and regions, 2009-Q1.

Source: BEA, US International Transactions Accounts Data, Tab.12: US International Transactions by Area, millions of dollars, not seasonally adjusted. The slope coefficient in the graph is significant at the 2% level.

For India, the relatively positive outlook is corroborated by Indian industry sources, which suggest that employment in the export-oriented IT and business process outsourcing services was expected to grow by about 5% (around 100,000 jobs) in 2009. Thus even during the crisis the industry continues to be a net hirer. While growth rates of both sales and employment are expected to be cut in half, this still leaves the sector with growth rates that would be considered buoyant in many manufacturing sectors.

Understanding the resilience of services trade

Based on new evidence from Indian services exporters, we find that services trade is buoyant for two reasons; low dependence on external finance and limited cyclicality of demand.

Differences on the supply side

On the supply side, services trade was less affected than goods trade by the crisis-induced scarcity of finance. In stark contrast to the manufacturing sector, tightening credit conditions did not noticeably constrain the production and export of services, for three reasons.

- First, the fact that many services are delivered electronically across borders, as digitised products, and occasionally through the movement of individuals to provide consulting onsite, obviates the need for traditional trade finance, the deteriorating availability of which hurt goods trade.

- Second, and apart from trade finance, when external funds are needed, e.g. working capital, factoring as a financial instrument continues to help meet financing needs for small and large firms alike.

Receivables in business process outsourcing are fungible and easily factorised because they typically involve a short-term transaction, a buyer who is creditworthy, and disputes over the service rendered are rare.

- Third, even before turning receivables into cash, many IT firms are able to leverage contracts in order to pre-finance working capital at the time when the order is placed, provided the contract involves a recognised party or government.

Generally, services-producing firms have even in normal times tended to be less dependent on external finance than goods production because they have limited tangible collateral. For example, two of India’s largest exporters of software and business-process services, Infosys and Tata Consultancy Services, have no external debt at all and rely completely on retained earnings for their operations.

Differences on the demand side

On the demand side, services exporters are still vulnerable to adverse demand shocks. However, demand for a range of traded services seems to have contracted less than demand for goods.

- One reason is that services are not storable and so are less subject to the big declines in demand in downturns that affect durable goods like shoes and televisions.

This is because many services suffer neither from the “vintage effect” – i.e. the willingness to wear an older pair of shoes or drive an older car – nor from the “inventory effect” – i.e. the fact that cuts in final demand translate into bigger immediate cuts in demand for factory output because of inventory adjustment.

- Another reason is that a larger part of international demand for services – e.g. outsourced back-office services – is less discretionary than demand for goods such as computers.

It is estimated that 70-80% of business in IT-enabled services can be characterised as non-discretionary. Trade in these services is likely to be insulated from negative demand shocks because they involve activities that must be carried on even during a crisis. For instance, in health care, a system-upgrading project (IT) is discretionary whereas the processing of claims (IT-enabled) has to continue. In banking, a project to realise end-to-end automation of payments (IT) is discretionary even though it might be cost saving, whereas transaction processing is non-discretionary.

- A third reason for the relative stability of services trade flows turns on the fact that a larger part of services trade seems to involve long-term relationships (e.g. because of relationship-specific investments by buyers and sellers).

There are also signs that the crisis is itself generating new tasks to be outsourced, such as legal process outsourcing or debt processing, as well as creating pressure generally to reduce costs through outsourcing.4

The subtle threat of protectionism

The relative buoyancy of services trade cannot be taken for granted. Over it too hangs the Damocles sword of protectionism. But protection is taking a subtle form, perhaps in deference to the invisibility of services and the fact that they are increasingly delivered electronically. First, explicit discrimination through preferential procurement seems at this stage less damaging than the implicit social and political disapproval of outsourcing. Developing country service exporters argue that it is the latter that has in some instances had a chilling effect on demand for their services. Similarly, the few visible explicit restrictions on employing or contracting foreign services providers in specific areas (e.g. financial services) are not as costly for both host and source as the increasing social and political aversion to immigration.

Another worry is the widening boundary of the state as a result of increased government ownership of firms during the crisis. Even though there is as yet no concrete evidence, there is a fear that state ownership could induce a national bias in firms’ choices on procurement and location of economic activity. In the longer term, subsidies to banks are probably less damaging than financial protectionism. The former are temporarily necessary to ensure the stability of the financial system. The latter seriously erode the case for openness. Inducing national banks to lend domestically in a crisis deprives developing countries in particular of capital when they most need it and greatly strengthens the case for financial self-sufficiency.

Conclusion

Findings from our ongoing research suggest that the buoyancy of services trade relative to goods trade was for two reasons:

- Demand for a range of traded services is less cyclical, and

- Services trade and production are less dependent on external finance.

Clearly more thorough investigation of these is needed, but if they hold up then there may be additional benefits to diversifying a country’s export structure towards services activities.

The apparent resilience of services trade may still be jeopardised by protectionism. Even though few explicitly trade-restrictive measures have so far been taken in services, the changing political climate and the widening boundaries of the state in crisis countries could introduce a national bias in firms’ choices regarding procurement and the location of economic activity. This is obscuring the economic stake that all countries have in open global services markets. While developing countries like India have seen rapid export growth, by far the largest exporters of these services are the US and EU members; the EU and US account for 65% of world services exports; China and India for 6%.

The US and EU have both consistently run a huge annual surplus on services trade, currently nearly $160 billion for the US and $220 billion for the EU. While US services imports from India and China have indeed grown to around $22 billion in 2008, US exports to these countries have expanded even faster, to over $26 billion. Even during the crisis US exports of key services are growing faster than its imports.

The US and EU have been powerful advocates of open services markets all over the world. Many developing countries have begun to reform their markets for communications, transport, financial, distribution and other business services. A retreat from openness in services in industrial countries could undermine reform efforts in developing countries, and even trigger a costly spiral of retaliatory protection.

Acknowledgments: This research project was supported in part by the governments of Norway, Sweden, and the UK through the Multidonor Trust Fund for Trade and Development, and by the UK Department for International Development.

Footnotes

1 This data also includes consumption of services abroad (in the category “travel”) but does not encompass sales through foreign affiliates or through the presence of foreign natural persons. See Maurer et al (2008) for details.

2 Part of the decline in the value of goods imports could be due to the fall in commodity prices. But note that US goods exports also declined by about one-quarter.

3 In annualised terms, this decline in the value of imports corresponds to 46.4 and 23.5% (goods and services, respectively), while exports fell by 42.3 and 17.8%.

4 Combinations of these factors may also lead to dynamic effects. Say, the pressure to reduce costs during the crisis induces outsourcing. Once a firm incurs sunk costs in establishing the new arrangement and relationship, it does not make sense to reverse the arrangement even after the crisis has passed. The temporary shock might thus permanently ratchet up outsourcing activity. The recent tendency of outsourcing providers to engage clients in multi-year framework agreements, under which individual transactions are being carried out, may also lead to a greater durability of business relationships.

References

Maurer, Andreas, Yann Marcus, Joscelyn Magdeleine, Barbara d’Andea (2008). “Measuring Trade in Services,” Chapter 4 in A. Mattoo, R. Stern and G. Zanini (eds), Handbook of International Trade in Services, Oxford University Press, Oxford.

Borchert, Ingo and Aaditya Mattoo (2009). “The Crisis-Resilience of Services Trade,” The Service Industries Journal, 30(14), December 2009, pp. 1-20. Also see working paper version, World Bank Policy Research Working Paper, No. 4917, April 2009.