Anaemic productivity growth and limited business dynamism remain key economic concerns in Europe and the US (Agresti et al. 2022). Policies to improve macroeconomic performance often target existing firms. Examples include tax measures to stimulate firm-level R&D and structural reforms to eliminate distortions in labour, financial, and product markets (Ciapanna et al. 2022). In this column, we investigate an entirely different policy lever, one that has so far remained largely unexplored: influencing the types of firms that enter the economy. Using a comprehensive new dataset on European startups, we show how tax policies that shift the composition of new startup cohorts could deliver meaningful macroeconomic gains.

Not all startups are the same

The idea of improving the composition of new startup cohorts (as opposed to ‘fixing’ established firms) appears attractive for two reasons. First, the rates of firm entry and exit are high, typically around 10% annually. This means that the majority of firms that will be in operation twenty years from now are yet to be founded, while many current firms will no longer exist by then. Second, forward-looking policies to shift the composition of startup cohorts are attractive because, across the board, new firms drive job creation and productivity growth (Decker et al. 2016).

Not all startups are the same in this regard, however. Whereas some entrepreneurs are simply interested in running a small and uncomplicated business, others aim to scale up their production as quickly as possible. Such ex-ante heterogeneity among newly established firms helps to predict their performance later in life (Sterk et al. 2021). It follows that policies that can successfully shift the mix of startup types that enter the economy may generate important and lasting macroeconomic impacts.

Clustering and classifying startups

To better understand how startups differ, we collect unique new data on European startups in collaboration with the Competitiveness Research Network (CompNet) (di Mauro 2014). The resulting dataset contains information on all startups established between 2002 and 2019 in Croatia, Denmark, Finland, France, Italy, Lithuania, the Netherlands, Slovenia, Spain, and Sweden.

Because startup type is not readily observed, we first classify newly established firms into different types. We do so by using K-means clustering, an unsupervised machine learning algorithm. We feed the algorithm five key variables that entrepreneurs decide on when starting their business: employment; the capital-to-labour ratio; total assets; the leverage ratio; and the cash-to-assets ratio.

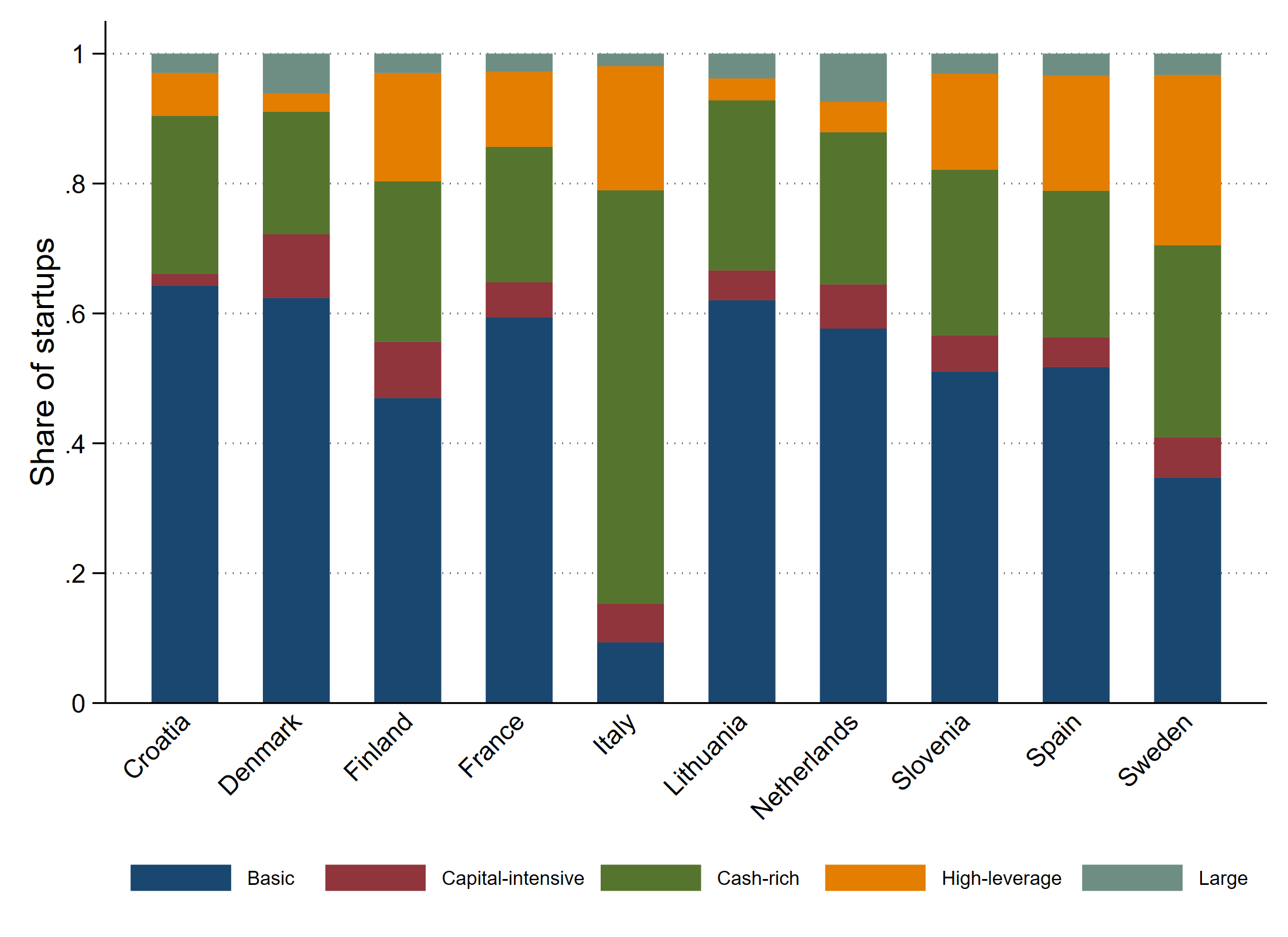

The algorithm reveals five well-separated clusters of startups, which we label large; capital-intensive; high-leverage; cash-intensive; and basic. This classification captures 50–70% of the variation in the abovementioned variables. An interesting stylised fact is that these five types are present in all countries (Figure 1), in all (broad) economic sectors, and in all startup cohorts – although their exact shares differ somewhat across countries, industries, and years.

Figure 1 Distribution of startup types by country

Notes: This figure illustrates the distribution of the startup population for individual countries across the five startup types. The startup population comprises all cohorts available for each country.

An analysis of these five startup types reveals distinct life-cycle patterns (De Haas et al. 2022). These types display large and persistent differences in employment generation, productivity, and exit rates. For example, the performance of the high-leverage type (which makes up 14% of all startups) is consistently poor. These young firms are more likely to exit than any other startup type, and their productivity and profit levels are relatively low. By contrast, startups that are capital intensive (7% of all startups) or cash-rich (26%) boast higher productivity levels and lower exit rates.

Corporate taxation as a policy instrument

Given the large differences in how startup types develop over time, the composition of new firm cohorts can potentially have significant macroeconomic effects. To provide insights into the economic relevance of this startup-composition channel, we calibrate a firm-dynamics model in the tradition of Hopenhayn (1992). This model describes an economy with many firms that each have their own production function and productivity level.

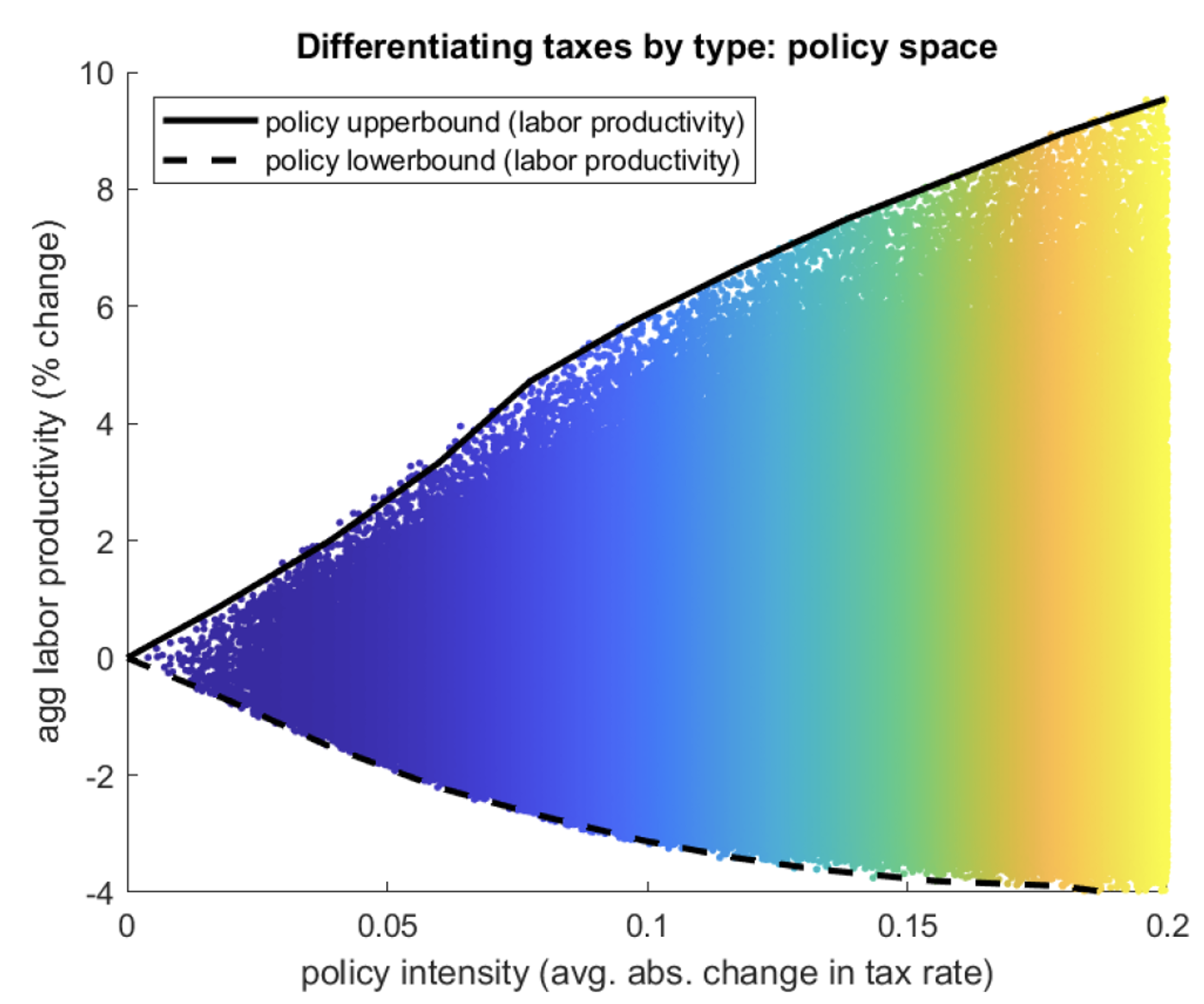

We use this model to evaluate the macroeconomic impacts of a budget-neutral change in corporate income taxation. More specifically, we analyse a large number of possible policies that differentiate between startup types in terms of the tax rate they face. Such changes obviously alter the incentives of different types to start operations and hence affect the startup mix. The model yields clear insights into how much aggregate employment and labour productivity may improve through the startup-composition channel.

We show that policies that benefit high-performance startups while at the same time discouraging the entry of underperforming ones can reap substantial macroeconomic gains. For instance, for a policy intensity of 0.1 – that is, a 10 percentage point change in the tax rate, on average – aggregate labour productivity can rise by 6% (Figure 2). This could be achieved by lowering taxes for the capital-intensive startups while financing this policy through an increase in the tax rate for the other startup types.

Figure 2 Policy experiment: Tax differentiation and aggregate productivity of young firms

Notes: This figure summarises the policy experiment. It shows the policy space for aggregate labour productivity. The horizontal axis measures the intensity of the potential policy change as the absolute change in the tax rate, averaged across firms. Warmer colours indicate stronger corporate tax rate differentiation. The solid line plots the policy upper bound: the largest possible aggregate labour productivity increase given a certain policy intensity.

As expected, this change in taxation shifts the composition of new startup cohorts towards more capital-intensive firms while reducing the share of basic startups. Since the former have much higher levels of labour productivity than the latter, aggregate labour productivity increases. A similar policy could achieve a 12% increase in aggregate employment when tax rates are cut for the large startup type and this is financed by an increase in tax rates for the cash-rich types.

Conclusions

Given high corporate entry and exit rates, policymakers aiming to improve macroeconomic performance may consider (tax) policies that explicitly target the composition of incoming generations of firms. The method outlined in this column is based on measurable criteria and therefore straightforward to implement. This not only makes it a potentially useful policy tool, but also a valuable complement to standard analyses of the macro effects of tax reforms, which typically ignore impacts on the composition of new startup cohorts.

Editors’ note: This column is published in collaboration with Bank Underground.

References

Agresti, S, F Calvino, C Criscuolo, F Manaresi and R Verlhac (2022), “Tracking business dynamism during the COVID-19 pandemic: New cross-country evidence and visualisation tool”, VoxEU.org, 17 January.

Ciapanna, E, S Mocetti and Alessandro Notarpietro (2022), “The macroeconomic effects of structural reforms: An empirical and model-based approach”, VoxEU.org, 1 July.

Decker, R, J Haltiwanger, R Jarmin and J Miranda (2016), “The decline of high-growth entrepreneurship”, VoxEU.org, 19 March.

De Haas, R, V Sterk and N Van Horen (2022), “Startup types and macroeconomic performance in Europe”, CEPR Discussion Paper No. 17400.

Di Mauro, F (2014), “Firm-level data: Who said that they are too difficult to use for policy?”, VoxEU.org, 11 March.

Hopenhayn, H A (1992), “Entry, exit, and firm dynamics in long run equilibrium”, Econometrica 60(5): 1127–50.

Sterk, V, P Sedlacek and B Pugsley (2021), “The nature of firm growth”, American Economic Review 111(2): 547–79.