How many people are homeless in the US? What is the extent of the economic deprivation they face, and how well are they reached by the social safety net? How does time spent homeless fit into these individuals’ long-term economic trajectories? These questions are fundamental to understanding America's homelessness crisis and for designing effective, well-targeted, and adequately scaled policies to address it. Yet despite widespread concern, these and other key questions are still unresolved, in large part because it is unclear whether available data are complete or reliable (O’Flaherty 2019, Mclean et al. 2020, Fetzer et al. 2020).

This is not surprising when one considers the considerable challenges faced by efforts to count or survey people experiencing homelessness. Because they lack a fixed domicile, homeless individuals cannot be counted using standard address list-based approaches. They must instead be found in the shelters, soup kitchens, encampments, or other locations where they happen to be staying (Glasser et al. 2014, Corinth 2015). And while local communities carry out their own canvassing operations each year for the Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD)’s point-in-time (PIT) counts, these operations have attracted criticism for their non-uniform methods and reliance on minimally trained volunteers (U.S. Government Accountability Office 2020, Meyer et al. 2021, Corinth et al. 2021).

In a new paper, we take an important step towards answering these first-order questions (Meyer et al. 2022). We start with the most fundamental question of all – that of the homeless population size – before turning to an assessment of the completeness and accuracy of available sources of data on homelessness. Along the way, we also learn about how well the Census succeeds at including this highly mobile and disconnected group of individuals in its decennial count.

Our approach centres on a triangulation of restricted and public-use datasets at the national, local, and individual level. We draw on publicly available data from the HUD's PIT counts and its associated Housing Inventory Count (HIC). We compare these to three restricted datasets: the 2010 Census, which counted both people in shelters and those at unsheltered locations, the American Community Survey (ACS), which includes those in shelters, and shelter use microdata from Los Angeles’s and Houston's Homeless Management Information System (HMIS) databases. This effort constitutes the first rigorous comparison of the PIT, which is widely cited in the media and used by HUD to allocate resources, to independent homeless population estimates.

We delve in particular into the coverage of homeless individuals in the 2010 Census and the ACS, two datasets that have rarely been used to study this population but hold tremendous promise. Among other advantages, they are designed to represent the entire US homeless population and can be linked at the person level to administrative microdata to unlock a wealth of additional information. Before we use these data to learn about homelessness, however, we need to understand how well they represent this population.

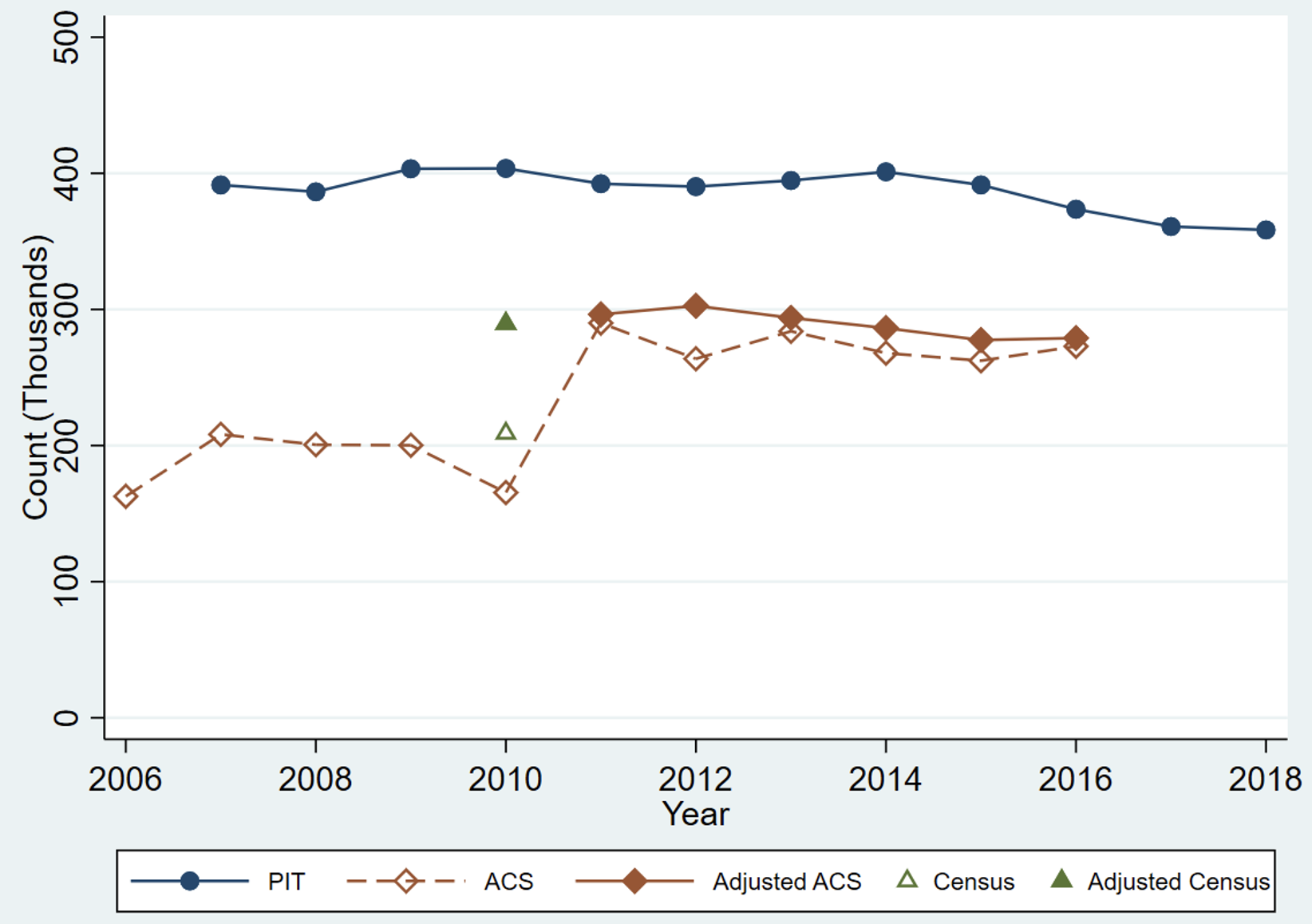

We start by considering aggregate homeless population estimates in the 2010 Census, ACS, and PIT. The 2010 Census counted 209,000 people in shelters and 210,000 in unsheltered locations, while the PIT from that same year counted 404,000 sheltered and 234,000 unsheltered people. The ACS sheltered estimates are similar to the Census after the introduction of a new survey frame following the 2010 Census and after accounting for bias arising from its weighting methods. At first glance, it looks like the Census and ACS might have missed some people who were included in the sheltered PIT, but in fact, we find that much of this discrepancy is due to straightforward definitional differences between the sources. In particular, unlike the PIT, the Census and ACS homeless estimates do not include people in domestic violence shelters or in hotel and motel beds funded by vouchers from homeless service providers. After adjusting the Census and ACS estimates upwards to reflect these definitional differences, we are left with a gap of around 100,000 people, as shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1 Sheltered homeless population estimates in the PIT, ACS, and Census with definitional and weighting adjustments

It is also notable that the Census and PIT arrived at similar unsheltered homeless population estimates. Whereas the PIT is planned and executed by local communities and uses different methods in each location, the Census developed its enumeration frame in a centralised fashion and employed uniform methods and training nationwide. Yet despite their methodological differences, these two sources arrived at population estimates that differ only by 24,000 people nationally. This finding bolsters the credibility of both sets of estimates, although it is of course possible that both missed people in ways we cannot assess with existing data.

Finally, we turn to the question of how well the Census included the homeless population overall and how well the ACS, which draws its sampling frame from the Census, represents those in homeless shelters. We address this question by linking microdata on Los Angeles and Houston shelter users from HMIS databases to the 2010 Census at the individual level. HMIS databases track shelter enrolment and exit dates for users of all federally funded shelters and many shelters without federal funding. Many communities extrapolate from these HMIS data to produce their PIT counts, so by linking these data, we can directly observe whether HMIS shelter users were included in the Census and thereby learn more about differences between the PIT and Census.

In both cities, we find that the Census included about 80–90% of people who were enrolled in HMIS shelters on the day of its homeless counting operation. Only about half of these HMIS enrolees, however, were included in the Census’s sheltered homeless count. The rest were counted in housing units, at unsheltered locations, or in other types of group housing facilities. Some of this apparent inconsistency likely stems from errors in the shelter exit dates recorded in HMIS, resulting in some people being incorrectly indicated as being in homeless shelters after they had in fact exited. We also find evidence that the Census considered some HMIS facilities to be conventional housing or other types of group quarters, like group homes for adults with disabilities or substance abuse treatment centres, rather than homeless shelters. For example, HMIS contains a large number of people in transitional shelters, where occupants are required to have a tenancy agreement and can stay for up to two years; the Census, on the other hand, appears to have classified many of these facilities as housing units. It also seems likely that many people responded to the Census while housed before entering or after leaving the homeless shelter during the nearly three-month window of potential Census response.

While investigating the coverage of HMIS shelter users in the Census, we also came across a surprising fact: the Census actually counted many homeless individuals twice, once as homeless and a second time as housed. This was true for about 20% of the sheltered and 40% of the unsheltered homeless. We considered whether this pattern could reflect linkage error or the misclassification of housed individuals, but the evidence points instead towards double-counting arising from homeless individuals' inclusion on the Census form of a family member or acquaintance with whom they occasionally resided. For example, most of these double-counted individuals were included on the housed Census record of a family member.

Taken together, our analyses suggest that there are approximately 500-600,000 people experiencing homelessness on a given night in the US. Of this number, about two-thirds reside in shelters while the rest sleep on the streets. The Census and ACS arrived at population estimates that are very similar to the PIT despite employing substantially different methods.

Given the considerable difficulties of surveying this population, we were also surprised to find such a high degree of coverage of homeless individuals in the Census. This is reassuring for future efforts to utilise the Census and ACS to learn about the homeless population by linking them to other data sources. Moreover, our observations on the Census’s frequent double-counting of homeless individuals sheds new light on this population's mobility and the fluidity of its transitions between housing statuses.

These results lay the foundation for path-breaking new analyses. In ongoing work, we link homeless individuals from the 2010 Census and the ACS to administrative data on employment, earnings, income, and safety net participation – an effort that allows us to observe these individuals' trajectories over the course of more than a decade and to learn about the causes and consequences of homelessness. We also plan to use these data to examine longstanding questions about the mobility and migration of people who experience homelessness and to produce the first national mortality estimates for this population. This research agenda promises to advance our understanding of the nature and extent of homelessness in the US and, in doing so, make a substantial contribution to efforts to address it.

References

Corinth, K C (2015), “Street Homelessness: A Disappearing Act?”, AEI Economic Perspectives, June.

Corinth, K, B Meyer, and A Wyse (2021), “Introducing a new dataset to better understand homelessness in the U.S.”, VoxEU.org, 25 July.

Fetzer, T, S Sen, and P Souza (2020), “Housing insecurity, homelessness, and populism: Evidence from the UK”, VoxEU.org, 27 February.

Glasser, I, E Hirsch, and A Chan (2014), “Reaching and Enumerating Homeless Populations”, in R Tourangeau et al. (eds), Hard-to-Survey Populations, Cambridge University Press.

U.S. Government Accountability Office (2020), “Homelessness: Better HUD oversight of data collection could improve estimates of homeless population,” GAO-20-433, July.

Maclean, C, J Mallatt, C J Ruhm and K Simon (2020), “A review of economic studies on the opioid crisis”, VoxEU.org, 20 December.

Meyer, B, A Wyse, A Grunwaldt, C Medalia, and D Wu (2021), “Learning About Homelessness Using Linked Survey and Administrative Data,” NBER Working Paper 28861.

Meyer, B, A Wyse, and K Corinth (2022), “The Size and Census Coverage of the U.S. Homeless Population,” NBER Working Paper 30163.

O’Flaherty, B (2019), “Homelessness research: A guide for economists (and friends),” Journal of Housing Economics 44: 1-25.