Around the world, women are massively under-represented at the top of the hierarchies in business, politics, and science. As of October 2021, women only constitute 31% of board members of the largest publicly listed companies in the EU 27. Less than 10% of these companies have a woman as the chairperson (8.5%) or CEO (7.8%).

The reasons behind the scarcity of women in top leadership positions across organisations, and in virtually all countries, remain a topic of ongoing discussion and debate.

Competition is often a necessity to ascend to the upper echelons of organisations and shatter the glass ceiling. And the literature suggests that competitive environments tend to favour men over women. We observe gender differences in: (1) performance in competitive environments (Gneezy et al. 2003, Gneezy and Rustichini 2004, Paserman 2007, Antonovics et al. 2009, Cardenas et al. 2012, Dreber et al. 2014, Booth and Yamamura 2017); (2) willingness to compete (Niederle and Vesterlund 2007, Gneezy et al. 2009, Booth and Nolen 2012, Buser et al. 2017); and (3) competitive choices (Gneezy et al. 2003, Niederle and Vesterlund 2007, Booth and Nolen 2012).

Overall, while men perform better than women in competitive environments, the difference in performance is found to be relatively small. Therefore, it is essential to investigate how a small gender performance gap, at the individual or ‘micro’ level, can contribute to the development of ‘macro’ level disparities. In recent research (De Sousa and Hollard 2022), we examine the link between micro and macro gender differences, using data from chess competitions.

The advantage of chess data

Our field setting is the game of chess, which offers several advantages with respect to the gender and competition literature. First, chess is played in official competitions all over the world. Second, male and female players compete against each other in tournaments. Third, players are ranked using a transparent, comparable and gender-neutral rating system, which provides us with an accurate performance measure that is rarely available in standard data. Chess is also played at all ages, from children and students, who are frequent subjects in lab and field experiments, to non-student adults and retirees. Fourth, chess allows us to use the entire distribution of Elo ratings to analyse gender differences in the chess hierarchy. And finally, we exploit game results to study gender differences in individual performance.

A macro gender gap

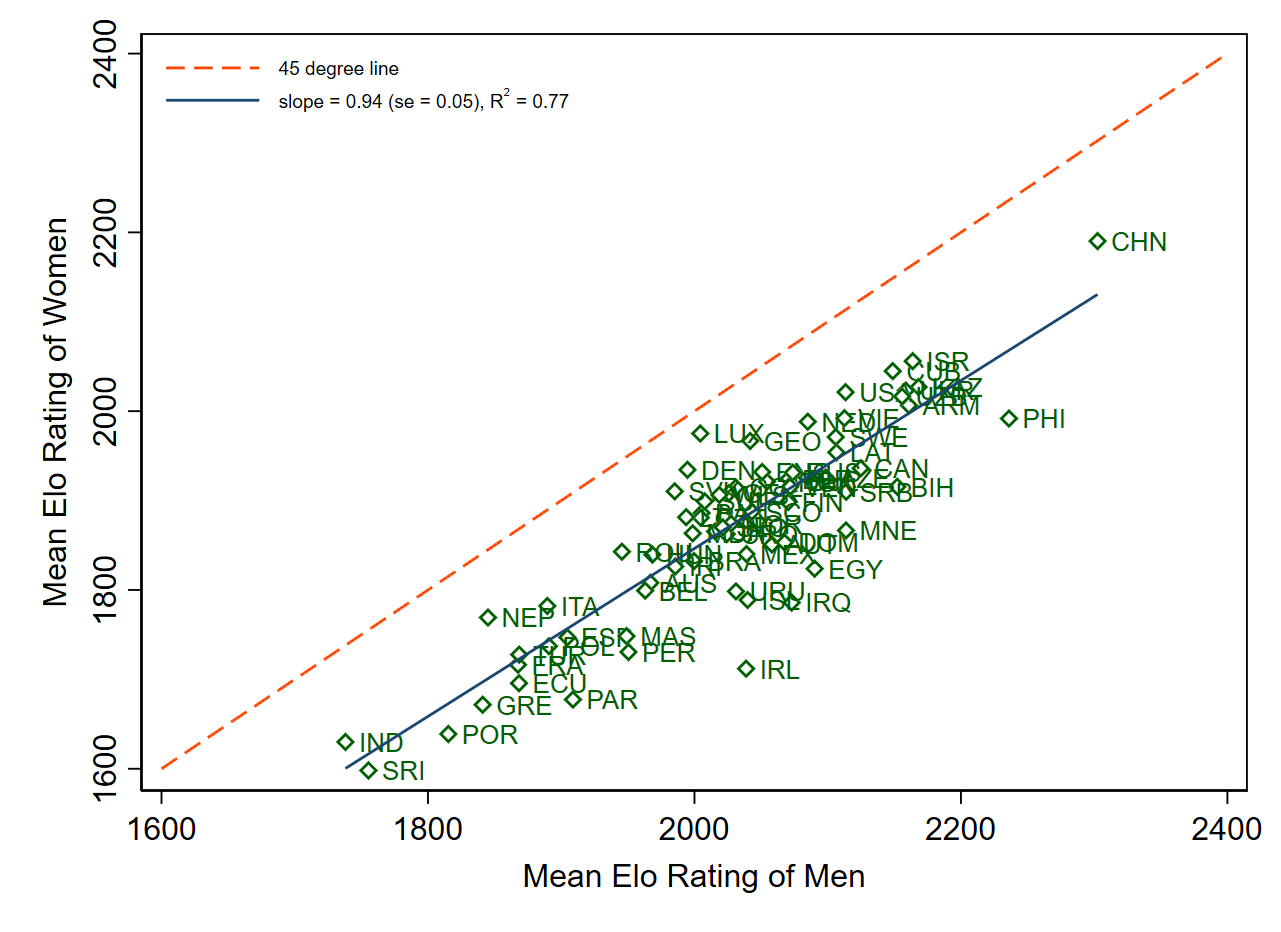

We first document the ‘macro gender gap’ by analysing national ranking distributions in over 150 countries. In any country, women have, on average, lower ratings than men, as shown in Figure 1. At the world level, the average gap between women and men is about 120 Elo points. The size of the gap shows that gender differences in chess competitions are substantial, so that an average woman has a 36% chance of winning against an average man.

Women are also less represented at the top of the hierarchy. As of August 2022, there is only one woman among the top 100 rated players and six in the top 500, even though women represent about 10% of rated players. We observe the same attrition along the hierarchical ladder within each country: there are fewer women than men, especially at the top. We therefore affirm a ‘leaky pipeline’ phenomenon that is also found in labour markets around the world.

Figure 1 The macro gender gap in 70 countries

Notes: This figure shows the correlation between men’s and women’s mean Elo ratings. We retain all countries with over 500 players in our sample (70 countries out of 161). We use ISO codes to represent the countries. The regression slope is 0.939 with a standard error (s.e.) of 0.052 and a R-squared of 0.771.

A micro gender gap

Using data from individual chess games, we compare the performance of women playing against men to counterfactual single-sex pairings in order to uncover a ‘micro gender gap’ in performance. Data covering millions of games enables us to use a large range of estimation techniques, including matching estimators. We find that a woman’s score is about 2% lower than expected when playing against a man rather than a woman with the same rating, age, and country.

This micro gender gap is found in virtually all countries, at all ages and persists with experience.

The magnitude of the micro gender gap appears robust to variation across countries, i.e. variation in culture but also in wealth, gender norms, and chess popularity. For instance, we find that the gender gap is of the same magnitude whether in the most female-friendly countries, such as Island or Norway, or in countries where gender inequalities are high, such as Iran or Pakistan.

The 2% lower chance of winning against men is equivalent to a 7 Elo point difference. A top-100 chess player who loses 7 points would drop an average of 4 positions. As such, the micro gap is small and women should still regularly be found at or near the top. The direct effect of the micro gender gap is too small to explain the macro gender gap, which is about 120 Elo points. However, the micro gender gap may explain a larger share of the aggregate gap, through what we call the accumulation hypothesis.

A simple theory of accumulation linking micro and macro levels

The goal of our study is to link the empirical facts at the micro level (small gender difference in performance) and the macro level (a gap sufficient to eliminate women from the top of the hierarchies). The question is whether these small effects accumulate to generate large overall gaps or whether their overall impact remains only limited.

Our simple theory suggests that the micro gender gap may have indirect and long-term consequences on human-capital accumulation and the likelihood that women drop out of competition. We set out a model in which male and female players are identical. The only difference is that women experience a small, and undetected, loss in their performance when playing against men, what we called the micro gender gap. We assume that players are uncertain regarding their overall ability and discover, game by game, how good they are at chess. So, they regard the outcome of their games as a signal of their underlying ability. As they lose relatively more often than men (because of the micro gap), women receive more negative signals regarding their own abilities. Women as thus slightly more pessimistic regarding their abilities.

Accumulation occurs because beliefs about ability are assumed to determine effort in chess. Players who are optimistic about their future success will invest more, while those who have moderate expectations may invest less or even consider leaving the competition. As women tend to become more pessimistic than men after each game, they also invest less than men. A small gap in success and effort can grow into a large one over time. As a result, the perceived benefits of competition are lower for women, leading to less investment in developing their skills and more dropping out of competition.

Conclusion

Our research suggests that small differences in routine interactions may contribute to gender disparities. These small differences can lead to women being perceived as less qualified, ultimately causing them to withdraw from competition.

The accumulation hypothesis changes the way we think about policy interventions. The ideal policy would target the accumulation process to prevent small gender differences – related to repeated and routine interactions – from becoming larger over time. What would a policy to limit accumulation look like? We know for instance that girls exposed to classroom interventions to foster grit are more optimistic about their future performance and more likely to persevere after initial failure (Alan and Ertac 2019). A gender affirmative action quota can also help increase women’s representation and performance (De Sousa and Niederle 2022).

Policies effective in helping women become more optimistic about their own abilities will limit accumulation, which relies on belief updating, and promote the acquisition of human capital. These interventions would facilitate the advancement of women and help break the glass ceiling.

References

Alan, S, and S Ertac (2019), “Mitigating the gender gap in the willingness to compete: Evidence from a randomized field experiment”, Journal of the European Economic Association 17: 1147–85.

Antonovics, K, P Arcidiacono, and R Walsh (2009), “The effects of gender interactions in the lab and in the field”, Review of Economics and Statistics 91: 152–62.

Booth, A, and P Nolen (2012), “Choosing to compete: How different are girls and boys?”, Journal of Economic Behavior and Organization 81: 542–55.

Booth, A, and E Yamamura (2017), “Performance in mixed-sex and single-sex tournaments: What we can learn from speedboat races in Japan", VoxEU.org, 14 March.

Buser, T, N Peter, and S C Wolter (2017), “Gender, competitiveness, and study choices in high school: Evidence from Switzerland”, American Economic Review: Papers and Proceedings 107: 125–30.

Cardenas, J-C, A Dreber, E Von Essen, and E Ranehill (2012), “Gender differences in competitiveness and risk taking: Comparing children in Colombia and Sweden”, Journal of Economic Behavior and Organization 83: 11–23.

Cubel, M (2017), “Women in competitive environments: Evidence from chess”, VoxEU.org, 8 January.

De Sousa, J, and G Hollard (2022), “From micro to macro gender differences: Evidence from field tournaments”, Management Science, forthcoming.

De Sousa, J, and M Niederle (2022), “Trickle-down effects of affirmative action: A case study in France”, NBER Working Paper w30367.

Dreber, A, E von Essen, and E Ranehill (2014), “Gender and competition in adolescence: Task matters”, Experimental Economics 17: 154–72.

Gneezy, U, M Niederle, and A Rustichini (2003), “Performance in competitive environments: Gender differences”, Quarterly Journal of Economics 118: 1049–74.

Gneezy, U, K L Leonard, and J A List (2009), “Gender differences in competition: Evidence from a matrilineal and a patriarchal society”, Econometrica 77: 1637–863.

Gneezy, U, and A Rustichini (2004), “Gender and competition at a young age”, American Economic Review 94: 377–81.

Niederle, M, and L Vesterlund (2007), “Do women shy away from competition? Do men compete too much?”, Quarterly Journal of Economics 122: 1067–101.

Paserman, D (2007) “Gender-linked performance differences in competitive environments: evidence from pro tennis”, VoxEU.org, 26 June.