Does one person’s criminal behaviour induce others to commit crime? Knowing if the answer is yes and, if so, the magnitude of such spillovers in criminal behaviour is essential for the optimal design and cost effectiveness of crime prevention policies.

Spillover effects in the behaviour of individuals give rise to ‘social multiplier’ effects (Glaeser et al. 1996). If there are social multipliers in crime, then this means that the costs of crime are underestimated if we limit ourselves to focusing on the primary perpetrator, since in addition to the primary effect, the crime may induce crime by others. It also implies that the benefits of reducing crime, by introducing effective crime prevention policies, are underestimated if one only focuses on primary effects through those affected by a programme.

Despite the importance of this question, there is little conclusive evidence of the existence of social multipliers in crime. One reason is that the causal link between two or more individuals’ criminal behaviour is difficult to establish empirically. It requires, first, a mechanism that exogenously changes the criminal behaviour of one individual; and second, measures of the effect this change has subsequently on the crime of the individual’s peers. In a recent paper we estimate the magnitude of spillovers from criminal behaviour in a group, using a novel identification strategy (Dustmann and Landersø 2018).

Our analysis proceeds in two stages. In step one, we focus on young males who father their first child at an age between 15 and 20 (which is the age range when criminal behaviour is highest). We establish a stark difference in the criminal behaviour of young fathers according to whether the child is a boy or a girl, which is a plausibly random event.

Young fathers of a boy receive, on average, one third fewer convictions for crimes in the first two years after the birth of their child compared with young fathers of a girl. This effect persists for at least three years. Thus, the gender of the child provides exogenous variation in the criminal behaviour of young fathers.

In step two, we measure how the young fathers’ immediate peers respond to the changed crime rates of young fathers, which are induced by child gender. Again, we find a strong effect, which is measurable for at least the next five years. These findings imply a large social multiplier in crime: over a five-year period, one crime committed by a crime-prone individual causes five additional new crimes by that individual’s peers.

Children’s gender and young fathers’ crime

Our analysis uses full population register data from Denmark on all males aged 20 or below when they fathered their first child between 1991 and 2004. The use of full population register data allows us to link these fathers not only to their new-born children, the mothers and other family members, but also to their residence and other young males who lived in their immediate neighbourhood when the child was born. We can also link individuals to crime registers from police and criminal courts, as well as other outcomes such as employment and education.

In Denmark, men who have a child before they turn 20 typically come from disadvantaged backgrounds. One in three has received a conviction for a crime committed before the child was conceived – three times the share of equally aged males on average. Once their first child is born, many of the young fathers continue to commit crimes. But we establish a sharp difference in crime rates after birth for those fathers whose child is a boy and those fathers whose child is a girl.

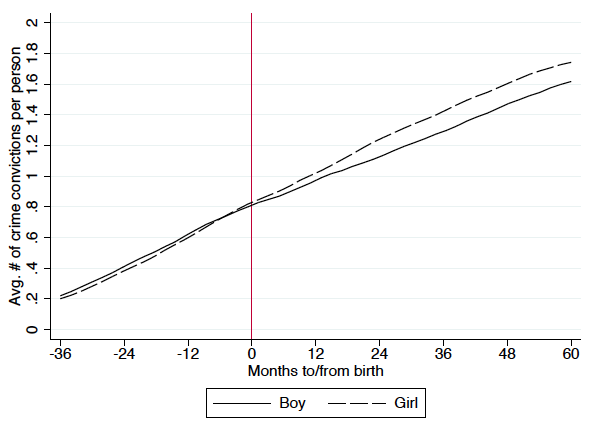

Figure 1 shows the accumulated number of crime convictions of young fathers from three years prior to their child’s birth to five years afterwards, distinguishing between the fathers of boys (solid line) versus girls (dashed line). While prior to the child’s conception, there are no differences between the average number of crime convictions for individuals who will later father a boy compared with a girl, after the child’s birth (indicated by the zero line), the two crime conviction rates diverge and the difference increases slightly over the next five years, with fathers of boys accumulating fewer convictions for crimes than fathers of girls. Sixty months after conception, fathers who had a boy have roughly 0.12 fewer crime convictions than fathers who had a girl.

Figure 1 Number of crime convictions and birth of a girl versus a boy

Note: The figure shows accumulated number of crimes per person around the time of childbirth (time 0) by gender of child, for the main sample of first time fathers aged 20 or below at time of childbirth.

Source: Own calculations based on data from Statistics Denmark.

What makes young fathers respond to their child’s gender in such a remarkable way? One interpretation is that the young fathers of boys become more aware of their responsibility to the child. Perhaps they now see themselves as a role model, and this feeling is stronger when the child is a boy.

Others have established different behavioural responses of fathers to the gender of their children (e.g. Lundberg and Rose 2002, Dahl and Moretti 2008). Washington (2008) finds that members of Congress vote differently on gender-related issues depending on the gender of their own children; and Bennedsen et al. (2007) show that fathers are more likely to hand over their company to their child if the first born is a son rather than a girl.

Spillovers in crime

Having established in the first step of our analysis that a child’s gender creates exogenous differences in the fathers’ level of criminal behaviour, in the second step we isolate the effect of this on the fathers’ peers. We focus on all males who lived in the narrow neighbourhood of the young father at the start of the year when the child was born, and whose age is within three years of that of the father.

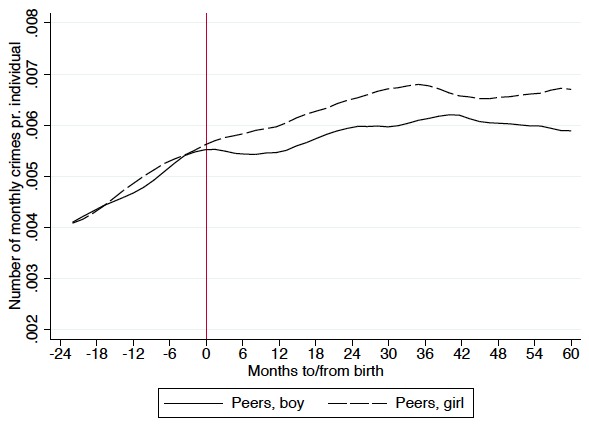

Figure 2 shows the evolution of the average monthly number of crime convictions for these peers, from 24 months pre-birth up until 60 months post-birth, with the solid and dashed lines representing neighbourhoods in which a boy or girl is born, respectively.

Whereas no differences in average crime conviction rates are observable among peers in girl-child versus boy-child neighbourhoods before the child’s birth, after the event rates drop noticeably in boy-child neighbourhoods. This gap opens in the first three years post-birth and remains roughly constant until the end of the observation period.

Figure 2 Number of crime convictions among neighbourhood peers, birth of a girl versus a boy

Note: The figure shows monthly number of crimes by males age 14-25 at time of childbirth per male person in main sample of father's neighbourhood before and after birth (time 0), by gender of child.

Source: Own calculations based on data from Statistics Denmark.

The effects we show in Figure 2 are not only detectable in terms of peers’ crime convictions. We also analyse how these changes affect potential victims, and find that victimisation rates change in the same way as crimes committed by young fathers and their peers. While there are no differences in the pre-birth period, victimisation rates become lower in neighbourhoods where young fathers have a boy than in neighbourhoods where young fathers have a girl.

In a wide range of tests, we find that young fathers of boys and girls do not differ in any aspect before their first child, and neither do their peers’ characteristics. Furthermore, in contrast to the young fathers, peers show no response in aspects other than crime, which means that it is unlikely that peers’ responses are related to other channels than fathers’ criminal behaviour.

We thus conclude that our analysis provides causal evidence for the existence of social multipliers in criminal behaviour. By comparing the magnitudes of the responses of young fathers and of their peers, we are further able to estimate this social multiplier underlying the spillover effects in criminal behaviour. We establish a multiplier close to five, which means that a reduction in the number of a young father’s criminal convictions by one will, in the following years, result in a total of five fewer convictions for him and his peers.

Implications

Using an identification strategy with exogenous variation in the criminal convictions of one focal individual, where variation is induced by the gender of his first child, our study adds support to the existence of spillovers in criminal behaviour and allows us to conclude that these spillovers are due to behavioural social interactions that generate multiplier effects.

By using the estimates to recover the parameters of a structural model of crime interaction (following Bramoullé et al. 2009 and Blume et al. 2015), our study illustrates further that an exogenous shock to a focal individual’s criminal activity is amplified through feedback to and between his peers and himself, thereby generating crime multipliers that continue to increase even after the primary impact of the initial shock has dissipated.

These findings suggest that the benefits from programmes that reduce crime at an early stage of a young person’s life are far larger than suggested by the primary effects alone.

References

Bennedsen, M, K M Nielsen, F Perez-Gonzalez and D Wolfenzon (2007), “Inside the family firm: The role of families in succession decisions and performance”, Quarterly Journal of Economics 122(2): 647-91.

Blume, L E, W A Brock, S N Durlauf and R Jayaraman (2015), “Linear social interaction models”, Journal of Political Economy 132(2): 444-96.

Bramuollé, Y, H Djebbari and B Fortin (2009), “Identification of peer effects through social networks”, Journal of Econometrics 150(1): 41-55.

Dahl, G B and E Moretti (2008), “The demand for sons”, Review of Economic Studies 75(4): 1085-1120.

Dustmann, C, and R Landersø (2018) “Child’s gender, young fathers’ crime, and spillover effects in criminal behavior”, CReAM DP 05/18.

Glaeser, E L, B I Sacerdote and J A Scheinkman (2003), “The social multiplier”, Journal of the European Economic Association 1(2-3): 345-53.

Lundberg, S, and E Rose (2002), “The effects of sons and daughters on men’s labor supply and wages”, Review of Economics and Statistics 84(2): 251-68.

Washington, E (2008), “Female socialization: How daughters affect their legislator Fathers’ voting on women’s issues”, American Economic Review 98(1): 311-32.