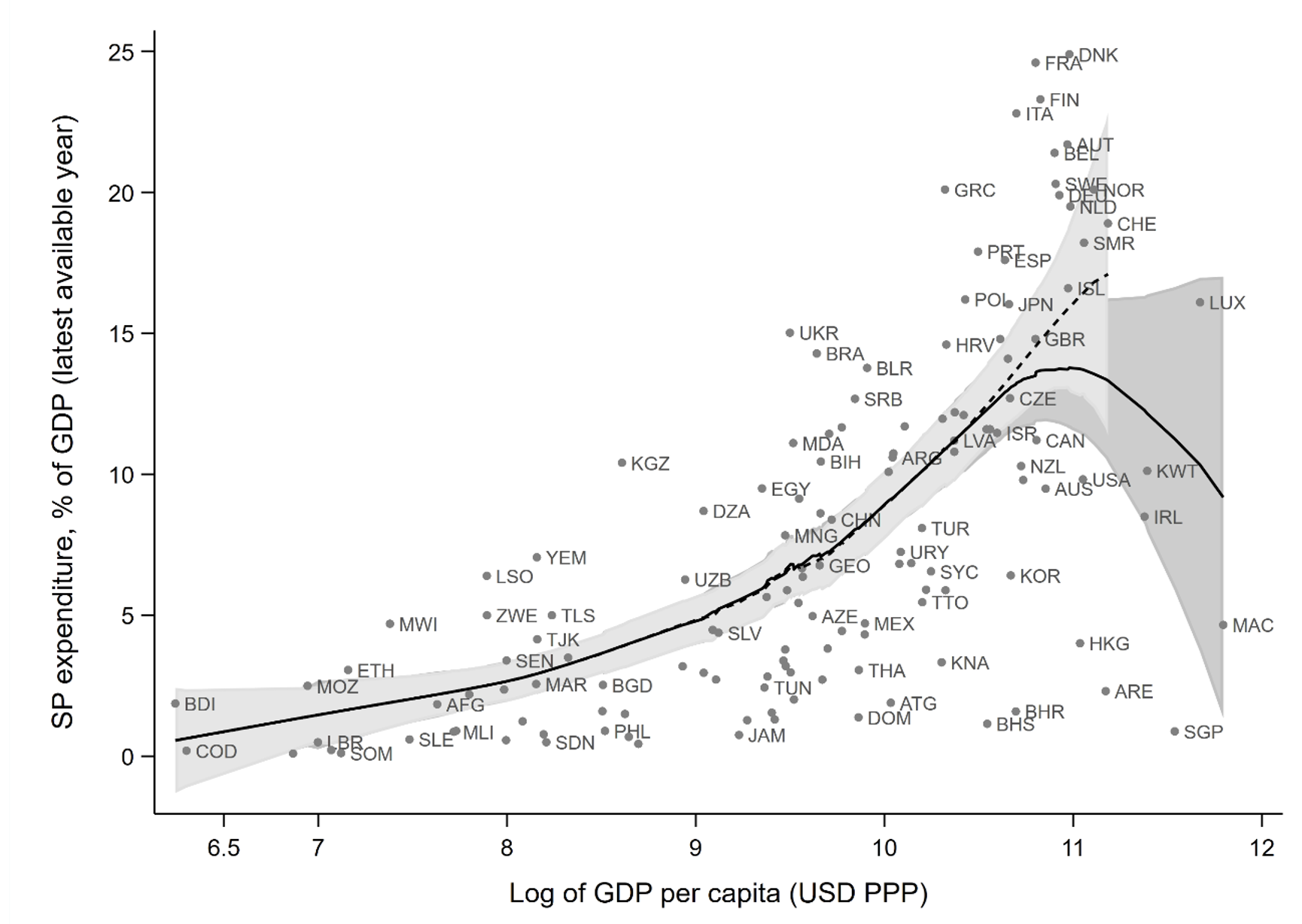

Higher-income countries devote a larger share of their GDP to social protection (SP) than do lower-income countries. Figure 1 plots the relationship between the share of GDP devoted to social protection and (log) GDP per capita across countries (for the last pre-pandemic year for which data are available). We see that the share devoted to social protection rises through almost the whole range of GDP, implying an overall income elasticity exceeding unity. The difference between rich and poor countries in the mean shares of GDP devoted to social protection is large; the share is 15% on average among the top quintile of countries ranked by GDP per capita, as compared to around 3% for the bottom quintile.

This pattern in the data has often been used to argue that social protection is a ‘luxury good’ at the national level—that, by revealed preference, poor countries have higher priorities than social protection. In keeping with this view, the classic policy reform packages for developing countries that emerged in the 1990s gave little attention to social protection; for example, social protection was not even mentioned in the famous ‘Washington Consensus’ (Williamson 1990). This view of social protection has been debated over the last two decades, with arguments being made for a greater emphasis on the developmental role of social protection in low- and middle-income countries; see, for example, Giovanetti and Sanfilippo (2011), with reference to Sub-Saharan Africa, and more generally Ravallion (2016) (Chapters 2 and 10). We have seen many new social protection programmes in developing countries and rising policy and scholarly interest (especially with regard to cash transfers for poverty reduction). Nonetheless, the lasting policy interpretation drawn from evidence such as Figure 1 is that, while social protection is an important task for governments in rich countries, it is less of a concern in poor ones.

However, the luxury good hypothesis is not the only explanation for the pattern in Figure 1. People in poor countries might care just as much (or possibly more) about social protection, but weak institutions, deficient infrastructure, and other conditions typical of poor countries, make it harder to convert their notional social protection demands into public spending—in short, that poorer countries face higher costs in effectively implementing this type of public spending. Prices of competing services (health and education) may also play a role to the extent that these services are relatively expensive in richer countries, encouraging substitution toward social protection transfers within public budgets.

Figure 1 Scatter plot of social protection spending as a share of GDP against log GDP per capita for the latest available pre-pandemic year

Source: Lokshin et al. (2022)

Note: The nonparametric regression line is a smoothed scatter plot (using the lowess command in Stata). The shaded area is the 95% confidence interval. The solid black line includes all the countries and the dashed one excludes the five richest countries as measured by their log GDP per capita (Macao, Luxembourg, Singapore, Kuwait, and Ireland). The Addendum to Lokshin et al. (2022) provides the corresponding graph deleting pension spending. Country codes are the U.N.’s Alpha 3 list.

In Lokshin et al. (2022) we formulate several alternatives to the luxury good hypothesis. The rival hypotheses relate to the relative prices for human development services, political economy (governmental accountability, the capacity for public service provision more broadly, and redistributive policy-making), the distributional impacts of economic growth, access to appropriate technologies, population aging, and the selection processes for observed public spending data.

We test these hypotheses using two new data sets on public spending on social protection globally. The first spans 142 countries over 1995-2020. The second data set focuses on the pandemic period 2020-21 and covers social protection programmes under the designated pandemic stimulus budget of each of 154 countries. The motivation for using this second data set is that, prior to the pandemic, the leadership of low- and middle-income countries may have wanted to see more resources devoted to social protection but faced ‘stickiness’ in budget allocations and difficulties in domestic resource mobilisation (e.g. Alesina and Passarelli 2019). A major shock can potentially break the hysteresis, revealing new priorities and expanding social protection systems where previously they had limited coverage (Gerecke and Prasad 2010).

Lessons learnt

We document evidence of rising public spending on social protection among initially poor countries, although our findings are more consistent with the view that economic growth in those countries has been driving this change rather than shifting policy priorities in favor of higher social protection at given GDP. Gains to social protection budgets have come more from countries moving along the Engel curve in Figure 1 rather than upward shifts in the curve with changing priorities.

Why then do we see the positive income effect on social protection shares in Figure 1? It is not due to latent effects at the country level; the income effect remains evident when one introduces country fixed effects, using our panel data set. In other words, social protection still appears to be a luxury good when focusing on the inter-temporal variances, although the slope of the income effect is attenuated considerably.

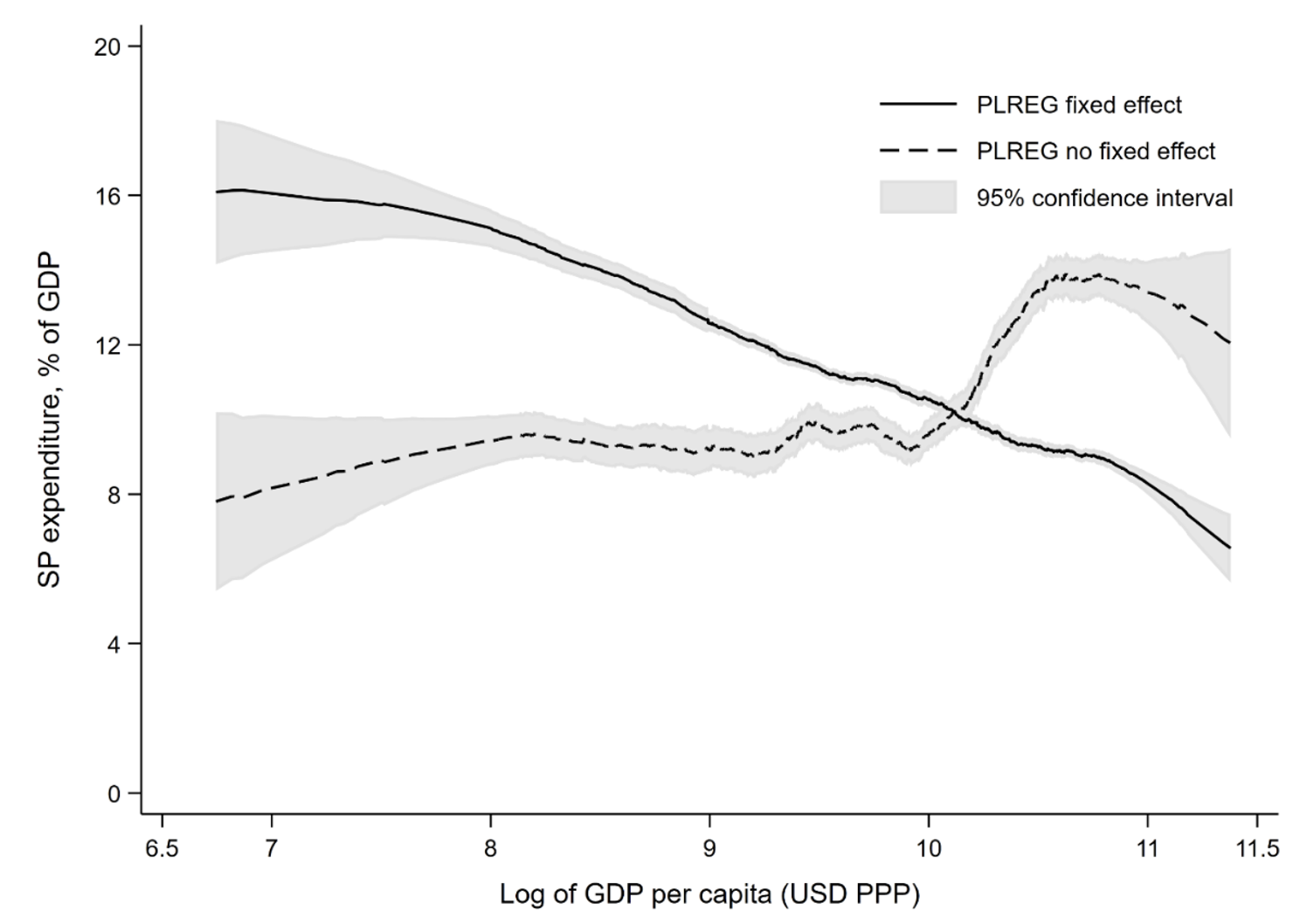

We find that the tendency for the social protection share to rise with national income is mainly attributable to the effects of multiple, time-varying confounders. Controlling for country fixed effects and for these confounding factors, the relation between the social protection share and per capita GDP is very different to Figure 1; indeed, the relationship turns negative, as shown in Figure 2. While we cannot be confident about the relative importance of specific confounders, Figure 2 is a clear rejection of the prevailing luxury good interpretation of Figure 1.

Echoing our findings using the pre-pandemic data, we also find that poorer countries devoted a smaller share of their GDP to social protection in response to the pandemic. However, here too, the luxury good interpretation is unconvincing. Relatively low public spending on social protection among poorer countries during the pandemic appears to have stemmed mainly from weak government effectiveness in public service delivery and younger populations rather than low income per se. Indeed, if one controls only for an index of government effectiveness, the share of GDP devoted to social protection during the pandemic is essentially no different between rich and poor countries.

Rather than interpreting low social protection spending in response to the pandemic (and indeed low total stimulus spending, including non-social protection components) as confirmation for the luxury good hypothesis, our results suggest that this reflects weaknesses in governmental effectiveness generally—weaknesses that are highly correlated with average income but still have a degree of independent variation. Beyond government effectiveness, other factors may also influence the design of social protection policies in the face of large shocks, such as societal characteristics like solidarity and agency (Lima de Miranda and Snower 2022).

Our findings also highlight the importance of exploring further how broader efforts to improve governance and access to technology in developing countries may help attain better social protection. Without success in such complementary efforts, poor and risk-prone countries may be caught in a vicious cycle whereby continuing weakness in these areas limits effective social protection, which helps maintain poverty.

Figure 2 Nonparametric relationship between social protection and income, pooling countries and years with and without country fixed effects and controlling for time-varying covariates

Source: Lokshin et al. (2022).

Note: The graph plots social protection spending as a percent of the GDP (vertical axis) against log GDP per capita, in USD PPP prices (horizontal axis) for the pooled sample of 142 countries over the period from 1995 to 2020. The (nonparametric) regression line controls for all covariates set at their overall mean levels. The estimation uses the “PLREG” program in Stata; for further details see Lokshin (2006).

References

Alesina, A and F Passarelli (2019), “Loss Aversion in Politics”, American Journal of Political Science 63(4): 936–947.

Gerecke, M and N Prasad (2010), “Social policy in times of crisis”, VoxEU.org, 10 October.

Giovanetti, G and M Sanfilippo (2011), “Social protection in Sub-Saharan Africa: Learning from experiences”, VoxEU.org, 23 January.

Lima de Miranda, K and D Snower (2022), “Socially blindsided: Social foundations of pandemic protection”, VoxEU.org, 27 August.

Lokshin, Michael, (2006), “Difference–Based Semiparametric Estimation of Partial Linear Regression Models”, Stata Journal 3: 377-383.

Lokshin, M, M Ravallion and I Torre (2022), “Is Social Protection a Luxury Good?”, Policy Research Working Paper 10174, World Bank, Washington, DC.

Ravallion, M (2016), The Economics of Poverty: History, Measurement and Policy, New York: Oxford University Press.

Williamson, J (1990), “What Washington Means by Policy Reform”, in J Williamson (ed.), Latin American Readjustment: How Much has Happened, Washington: Institute for International Economics.