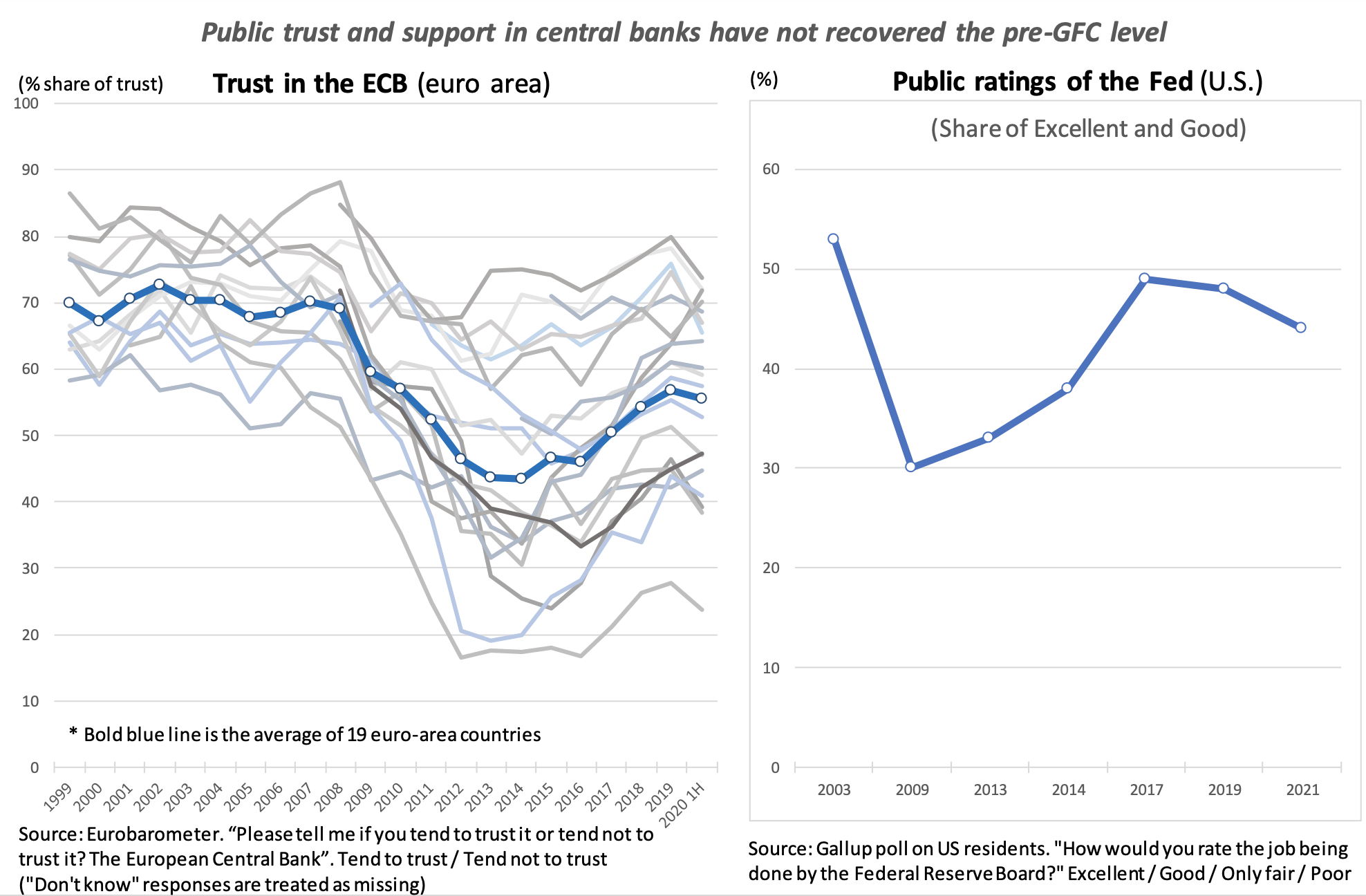

A large and growing literature has shown that central bank transparency delivers stabilisation benefits (e.g. Ehrmann et al. 2012). However, it is relatively silent on how communication affects citizens’ trust in central banks (Haldane and McMahon 2018). Trust is indispensable for democratic legitimacy, independence, and policy effectiveness, and it increasingly motivates central bankers to communicate more with the public. In their authoritative survey of the literature, Blinder et al. (2022) argue that building trust may be the most important objective of central bank communication with the general public. However, they point to severe limits on what this communication can be expected to achieve. Figure 1 shows that public trust in the ECB and the Fed has not recovered the pre-global financial crisis levels despite a great deal of communication efforts.

In a recent interview, Executive Board member Isabelle Schnabel (2022) emphasised that people’s trust in the ECB represents a condition for its success. For this reason, the ECB would strive to explain complex issues as simply as possible. However, they would not yet have succeeded in addressing their audience with simple words. This state of affairs needed improving and required spending a lot of energy on communication activities.

Figure 1 Trust in the ECB and public ratings of the Fed

ECB communication and trust

Previous work on public trust in the central bank has been conducted on the ECB, given the availability of Eurobarometer survey data (Gros and Roth 2009, Ehrmann et al. 2013, Bursian and Fürth 2015, Roth and Jonung 2019). However, the role played by ECB communication in the trust-building process has not been examined with the exception of Brouwer and de Haan (2021) who performed a random controlled trial among Dutch households. In recent work (Hwang et al. 2022), we investigated whether the Eurosystem’s actual speeches delivered over the period 1999 to 2019 have affected laypeople’s trust in the ECB.

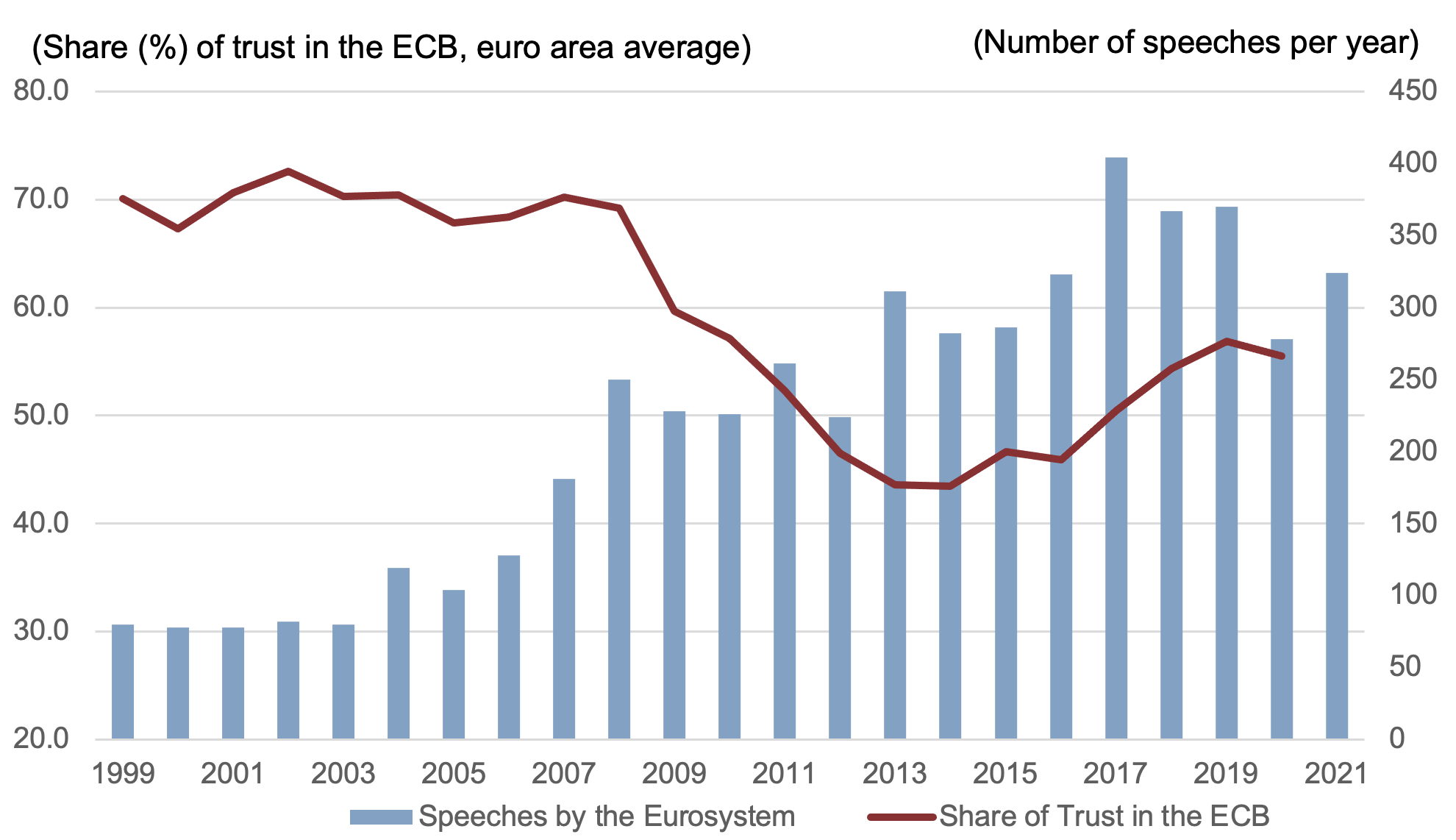

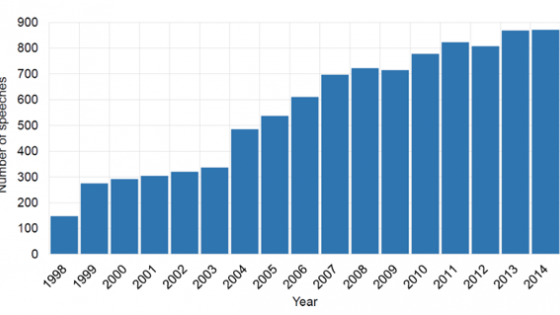

Figure 2 shows the number of Eurosystem speeches that we compiled from the BIS central bankers’ speeches database together with the evolution of trust in the ECB. Trust was relatively high and stable until 2008 but weakened due to the global financial crisis, the European sovereign debt crisis and Brexit (Schnabel 2020). The economic recovery triggered an upturn in trust but never reached the pre-crisis levels. The number of speeches has trended upwards since 2005 and reached an upper limit in 2017 with about 400 speeches per year.

Figure 2 Eurosystem speeches and trust

Notes: The line shows the evolution of trust in the ECB and the bars the number of speeches per year from 1999 to 2021.

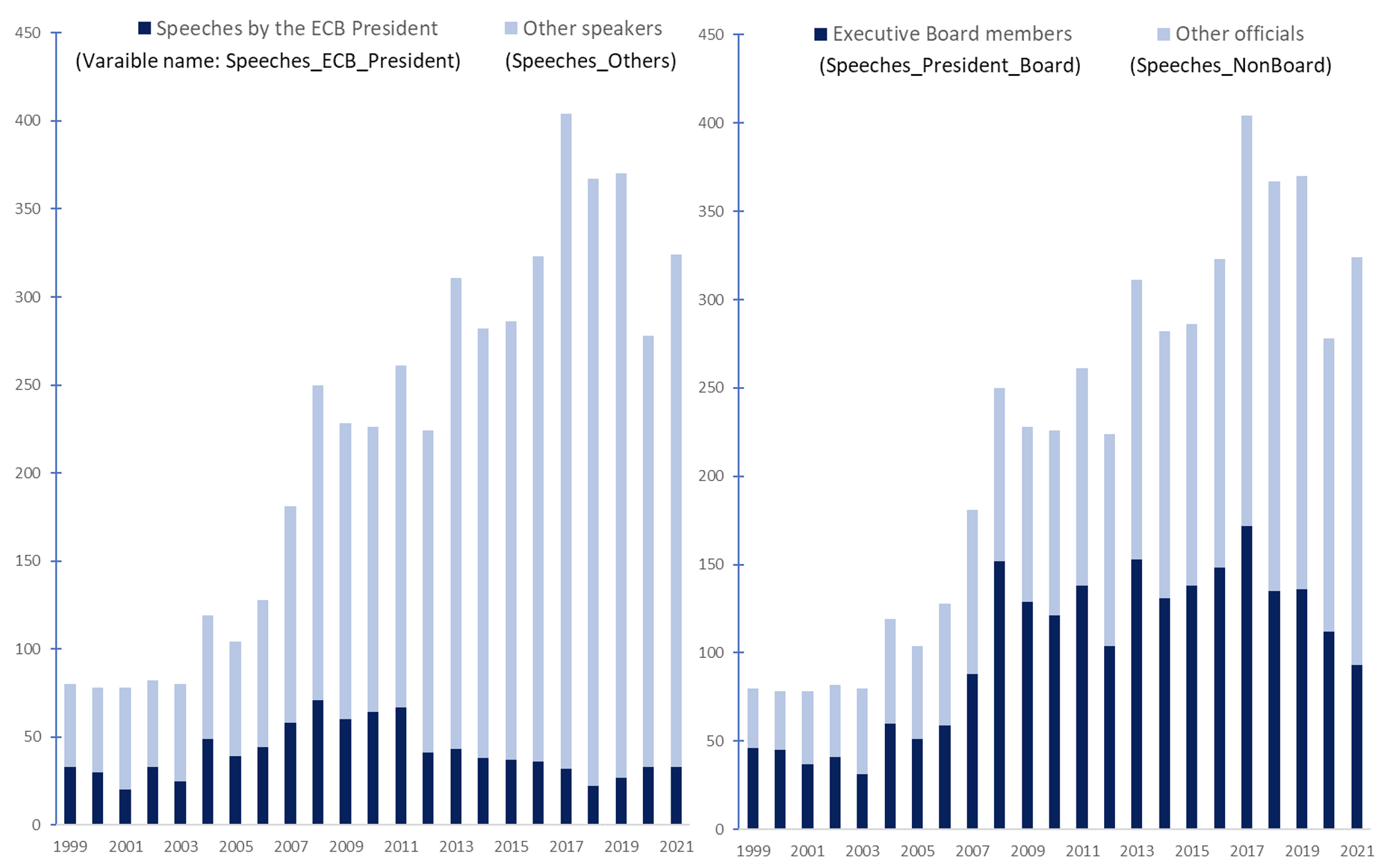

Figure 3 illustrates the quantity of Eurosystem speeches divided into four main groups of speakers: (i) speeches by ECB presidents, (ii) those of the rest of speakers (Panel A), (iii) speeches by the Executive Board and (iv) those of country representatives’, that is, non-board members outside the ECB’s headquarters (Panel B).

Figure 3 Number of Eurosystem speeches per year by groups of speakers

Empirical evidence

To answer our research question, we ran panel regressions using trust as the main endogenous variable and the sum of Eurosystem speeches next to those of the four different groups of speakers presented in Figure 3 as the main exogenous variables. In total we exploited the responses of 488,000 euro area citizens and 4,462 speeches. The evidence from individual-level linear probability models, country-level fixed effect models, and the GMM suggests that the quantity of speeches reduces trust. This holds for all types of speeches except for those of country representatives, which exhibit unstable results. Speeches by ECB presidents and members of the Executive Board produce the strongest reduction in trust. During the global financial crisis and the European sovereign debt crisis, the effect size even strengthened relative to the magnitudes observed during non-crisis periods.

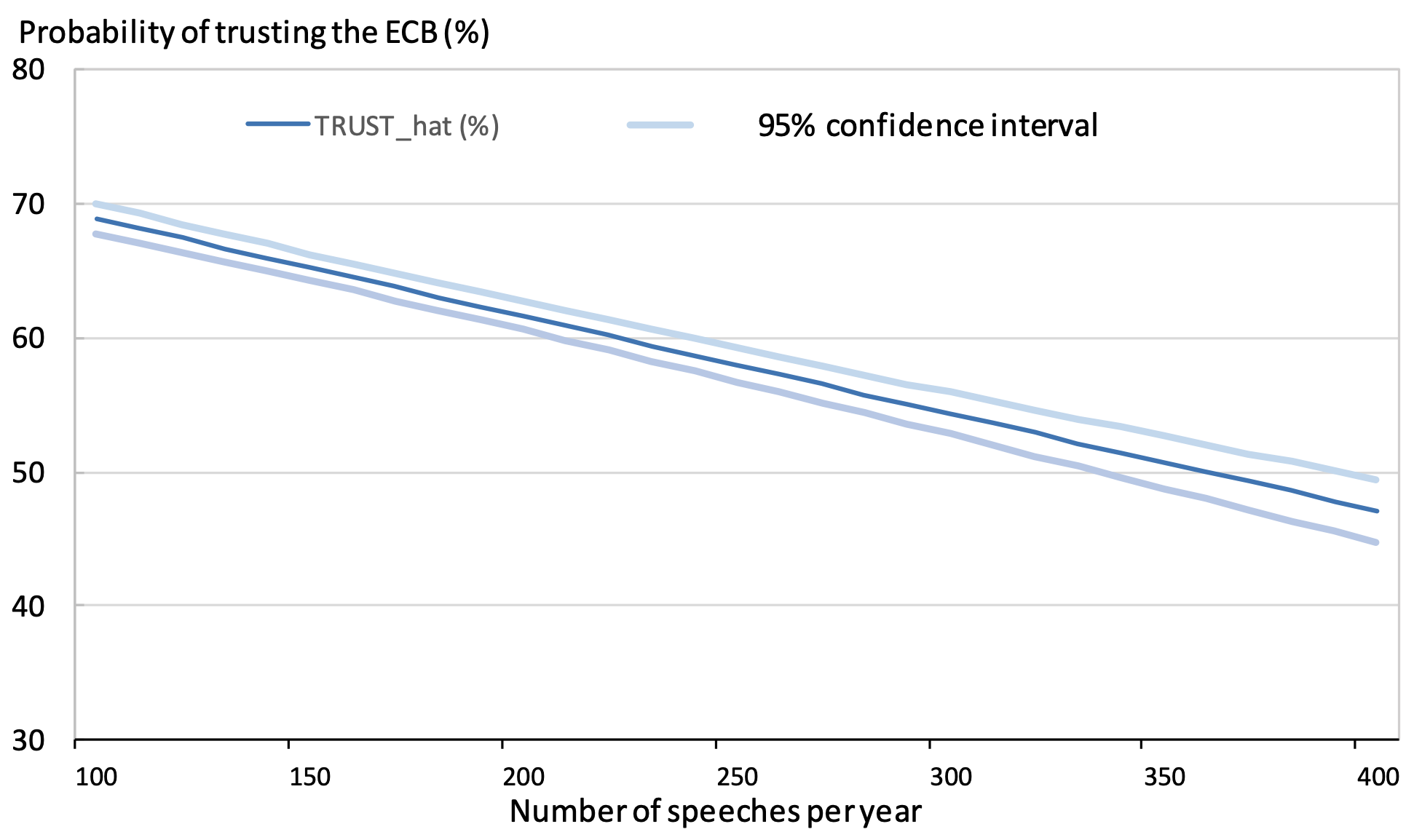

Figure 4 illustrates the fitted probability of trusting the ECB. An increase in the quantity of speeches per year steadily lowers citizens’ probability of trust. While 100 speeches per year correspond to a trusting probability of approximately 70%, 400 speeches per year lead to a drop in this probability to 47%.

Figure 4 Number of speeches per year and trust

Notes: Values other than speeches are held constant at the median values of eurozone respondents: 48-year-old married and working female exhibiting 11 years of education, a political orientation of 2 (center), and a degree of life satisfaction of 3 (fairly satisfied). The 95% confidence interval is very narrow because the regression is based on large number of observations (330,879), which drastically reduces the standard errors.

Other determinants of trust

In line with previous work, we found that socioeconomic factors also influence trust. Importantly, however, they do not change the main message. Individuals with a high education level and with higher knowledge on the EU are less susceptible to reducing trust than others. Overall, however, more talk seems to backfire even among more educated people. Macroeconomic conditions also play a role but do not change the main message either. In detail, GDP growth and, more interestingly, a higher policy rate tend to increase trust. In contrast, higher unemployment, financial stress, and policy uncertainty cause a loss in trust. More puzzling is that an increase in public debt also lowers trust in the ECB whereas inflation turns out to be irrelevant in most cases, despite great efforts by the ECB to boost its level. This raises a question: are central banks barking up the wrong tree? From the comparison between the negative reactions to increasing public debt and the neutral response to inflation, we may infer that citizens fear public debt but not for its potential impact on inflation.

Explanations

On a positive note, we found that speeches promote peoples’ informedness by raising the number of individuals who have heard about the ECB and those who have knowledge on the EU. These results indicate that citizens are receptive to central bankers’ speeches but respond by putting less trust in the central bank. This contrasts with recent research on communication and inflation expectations according to which neither households' nor firms' expectations respond much to monetary policy announcements in low-inflation environments (Coibion et al. 2019, Coibion et al. 2020a). Coibion et al. (2020b) concluded that while the “Fed Listens”, the public may not.

While the evidence is unequivocal, the reasons why speeches undermine public trust are not obvious. One possibility is that the complexity of the language used by central bankers breeds mistrust (Haldane, 2017). This is in line with our findings that more educated people react less negatively to speeches. However, an additional analysis yields that business managers who are likely to grasp the technical jargon used by central banks respond to more speeches by a negative assessment of the ECB’s economic impact. By combining these two results we hypothesize that complexity of subjects treated and the sophistication of language used in a speech cannot tell the (whole) story.

Another reason could be the ECB communication’s focus on market participants and monetary policy experts, neglecting to promote the public’s understanding of central bank policies (Schnabel, 2020).

Further, a cacophony of voices resulting from a fundamental trade-off between more transparency/communication at home, which is essential for trust, and the alignment of diverging developments and views across countries, might arise and confuse the recipients of the messages. Corroborating this hypothesis, we found that speeches impact more negatively on trust the less integrated euro countries are in terms of growth. This echoes the difficulty a lack of convergence within EMU countries poses for reaching a broad and heterogenous audience pointed out by Schnabel (2020).

Another interpretation is that the ECB is (mis)used as a scapegoat for developments which are outside its remit, especially during crisis periods. The result that the negative effect of speeches was exacerbated during the global financial crisis and European sovereign debt crises is in line with this conjecture.

A further alternative reading of the evidence is that trust-building is a complex undertaking that takes many years, arguably more than 20 years, especially when policy makers have to navigate large stretches of stormy water.

Central bank speeches can be interpreted as reflecting their presence in the media. This suggests that the most plausible and straightforward explanation of our results is that an increasing disclosure of information – a too intense central bank presence in the media – poses limits to its processing (Kahnemann 2003). This interpretation is consistent with a line of literature warning that excessive provision of information by central banks may lead to “information overload and confusion” (Van der Cruijsen et al. 2010: 1483) and “weaken support for a central bank” (Mishkin 2004: 26).

Conclusions

Eurosystem speeches appear to reduce the trust citizens pose in the ECB. What exactly causes this result is an unresolved issue. We provide some explanations, including (i) people’s limit to process large amounts of information which leads them to harbour suspicions of a central bank’s policies, (ii) a cacophony problem, and (iii) the possibility that the ECB is used as a scapegoat for outcomes for which it is not responsible. Whether our results hold in other currency unions cannot be told for the lack of comparable surveys. That said, the evidence we found for trust in the ECB are qualitatively comparable with studies that report negative effects of central bank speeches in large country samples with respect to forecast accuracy (Lustenberger and Rossi 2018) and business executives’ assessment of central banks’ impact on the economy (Hwang et al. 2021). The main policy implication from our analysis is that there may be the need to coordinate the quantity of public talks to enable market participants, professional forecasters, firms, and households to take in their messages as intended.

Authors note: The views, opinions, findings, and conclusions or recommendations expressed in this column are strictly those of the authors. They do not necessarily reflect the views of the Bank of Korea, the Swiss Financial Market Supervisory Authority (FINMA) or the Swiss National Bank (SNB). The Bank of Korea, FINMA and the SNB take no responsibility for any errors or omissions in, or for the correctness of, the information contained in this column.

References

Blinder, Alan S, M Ehrmann, J de Haan, and D-J Jansen (2022), “Central Bank Communication with the General Public: Promise or False Hope?”, DNB Working Paper No. 744 / April 2022.

Brouwer, N and J de Haan (2021), “Central bank communication with the general public: effective or not?”, SUERF Policy Brief No 57.

Bursian, D and S Fürth (2015), “Trust Me! I am a European Central Banker”, Journal of Money, Credit and Banking 47(8): 1503–1530.

Coibion, O, Y Gorodnichenko, M Weber (2019), “Monetary policy communications and their effects on household inflation expectations”, VoxEU.org, 22 February.

Coibion, O, Y Gorodnichenko, S Kumar, M Pedemonte (2020a), “Inflation expectations as a policy tool?”, Journal of International Economics 124, 103297.

Coibion, O, Y Gorodnichenko, E S Knotek II, R Schoenle (2020b), “Average inflation targeting and household expectations”, VoxEU.org, 30 September 2020.

Ehrmann, M, Eijffinger, S, & Fratzscher, M (2012), “The role of central bank transparency for guiding private sector forecasts”, The Scandinavian Journal of Economics 114(3): 1018-1052.

Ehrmann, M, M Soudan, L Stracca (2013), “Explaining European Union Citizens’ Trust in the European Central Bank in Normal and Crisis Times“, Skandinavian Journal of Economics 115(3): 781–807.

Gros, D and F Roth (2009), “The crisis and citizens’ trust in central banks”, VoxEU.org, 10 September.

Haldane, A, & McMahon, M (2018), “Central bank communications and the general public”, AEA Papers and Proceedings 108: 578-83.

Hwang, I D, T Lustenberger, and E Rossi (2021), “Central bank communication: Remember who’s talking“, VoxEU.org, 12 May.

Hwang, I D, T Lustenberger, and E Rossi (2022), “Central Bank Communication and Public Trust: The Case of ECB Speeches”, available on SSRN.

Kahnemann, D (2003), “Maps of Bounded Rationality: Psychology for Behavioral Economics", American Economic Review 93(5): 1449–1475.

Lustenberger, T, and E Rossi (2018), “More frequent central bank communication worsens financial and macroeconomic forecasts“, VoxEU.org, 04 March.

Mishkin, F S (2004), “Can central bank transparency go too far?”, NBER Working Paper 10829.

Roth, F, and L Jonung (2019), “Public support for the euro and trust in the ECB: The first two decades”, VoxEU.org, 13 December.

Schnabel, I (2020), “The importance of trust for the ECB’s monetary policy”, Speech at the Hamburg Institute for Social Research, Frankfurt am Main, 16 December.

Schnabel, I (2022), Interview with Süddeutsche Zeitung am Wochenende, 15 January 2022.

Van der Cruijsen, C A, S C Eijffinger, and L H Hoogduin (2010), “Optimal central bank transparency”, Journal of International Money and Finance 29: 1482–1507.