The 2016 US presidential campaign and the resulting election of Donald Trump have put immigration back at the centre of US policy debates. But this is not the first time in American history that immigration has become a divisive issue. Nearly a century ago, the rise in Southern and Eastern European immigration turned into a source of increased social and political tensions in the US. Much like some immigrants today, these ‘new immigrants’ were perceived by sectors of the US as being unlikely to assimilate. Following mounting social and political pressures, Congress convened a special commission in 1907 to analyse the social and economic life of immigrants to the US. The Immigration Commission painted a dismal picture of Italians, the largest contributors to the surge of southern European immigration: Italians consistently ranked at the bottom in terms of family income, rates of home ownership, and job skills (Dillingham 1911). The conclusions of the Commission served as the basis for country-of-origin quotas, which in 1924 limited the number of new Italian immigrants to just 4,000 per year (relative to an average of nearly 200,000 new Italian arrivals per year in the previous decade).

The situation of Italians in the US contrasts with their situation in Argentina, the second largest destination for Italians during the age of European mass migration. For instance, in 1909 Italians owned 38% of the 28,632 commercial establishments in Buenos Aires, despite comprising just 22% of the city’s population (Martínez 1910). According to another study, “the sharp differences in the Italian immigrant experience within Argentina and the United States were fully perceived by both the immigrants themselves and virtually all contemporary observers” (Klein 1983).

The reasons for these differences are less clear. Were the Italians who went to Argentina better prepared for the migration experience than those who went to the US? Or did they encounter a more welcoming host society? Existing studies on this issue are mostly based on population censuses from the receiving countries, data that make it difficult to tease out different explanations. For instance, though Argentina attracted a higher fraction of northern Italians, neither Argentine nor US censuses include information on the regional origins of Italians.

In a recent paper, I study the selection and economic outcomes of Italians in Argentina and the US during the age of mass migration (Pérez 2019). By assembling new individual-level data following Italian immigrants from passenger lists to population censuses, I am able to observe the year of entry, port of origin, and pre-migration occupation of a sample of Italians who resided in Argentina or the US by the late 19th century. I can then assess the degree to which differences in economic outcomes at the destination countries can be explained by differences in the pre-migration characteristics of those choosing one destination country over the other.

First, I use passenger lists to compare the pre-migration characteristics of Italians who moved to each country. The main difference between the groups was the higher fraction of Italians departing from northern ports among those going to Argentina. I find little difference in pre-migration occupations or other demographic characteristics: Italians who moved to Argentina or the US were of similar age and gender, and were employed in similar (predominantly unskilled) occupations prior to emigrating.

Next, I compare the outcomes of Italians in Argentina to those in the US using the passenger lists linked to census data, which allows me to narrow the comparison to immigrants who left Italy in the same year, from the same port, and with the same pre-migration occupation and literacy level. Even when comparing Italians of the same regional origin and with the same pre-migration occupation, Italians in Argentina had higher rates of home ownership and were more likely to hold skilled occupations than Italians in the US. Moreover, when I further restrict the comparison to Italian immigrants who shared a surname (thereby providing information about regional origins) but moved to different destinations, Italians still had better outcomes in Argentina.

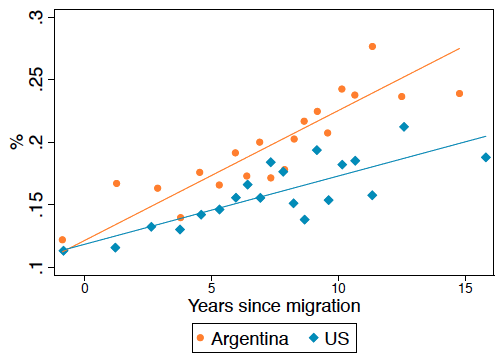

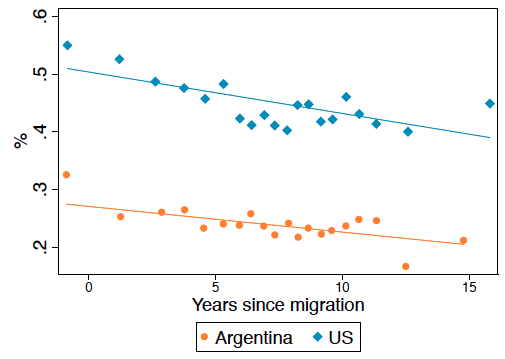

Figure 1 illustrates these findings. It shows rates of homeownership (panel a) and the likelihood of holding an unskilled occupation (panel b) as a function of years spent in the destination country. In both countries, a longer stay was associated with a higher likelihood of home ownership and a lower likelihood of holding an unskilled job. However, Italians in Argentina became homeowners earlier and had a much lower likelihood of being employed in an unskilled occupation than in the US.

Figure 1 Economic outcomes, by years since migration

a) Home ownership

b) Unskilled occupation

Which host-country conditions can explain the differences in economic outcomes? First, I show that although Italian immigrants in Argentina and the US had similar levels of human capital (as proxied by literacy and numeracy rates), Italians in Argentina had higher levels of human capital relative to the native-born population. Second, I find evidence that the closer linguistic distance between Italian and Spanish enabled Italians to enter a broader range of occupations (specifically, non-manual jobs) in Argentina than in the US. I also provide qualitative and historical survey evidence showing the widespread prejudice against Italians in the US during this period.

The large differences in economic outcomes and the likely limited role of pre-migration characteristics pose a puzzle. In an era of nearly open borders for European immigrants, why did some Italians choose a country that offered them limited prospects for upward mobility? One potential explanation is this: although upward mobility was slowed, wages for unskilled workers were higher in the US than in Argentina. Hence, Italians deciding between Argentina and the US might have faced a trade-off between higher wages in the short-term and better long-term prospects for upward mobility. However, the fact that Italians in Argentina and the US had similar arrival ages and rates of return migration is not entirely consistent with this explanation.

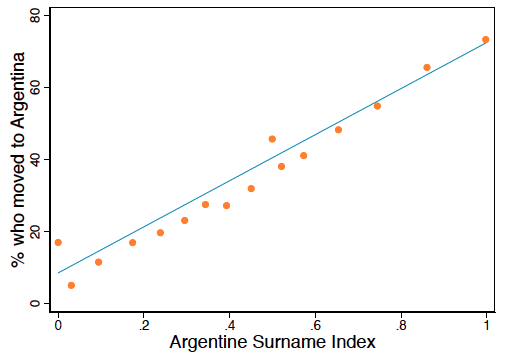

An alternative explanation is that immigrant networks generated path dependence in destination choices: for Italians choosing where to migrate, having relatives or friends in one of the destinations might have been the decisive factor. Because I cannot directly observe an individual’s family or friendships with past immigrants, I test this hypothesis by using the surnames of previous migrants to Argentina and the US to construct a proxy for the size of a migrant’s network at each potential destination. This measure seeks to capture whether migrants were more likely to move to destinations where persons with their surname had migrated previously.

Figure 2 shows the association between this measure (‘Argentine Surname Index’) and the likelihood of moving to Argentina. A value of one in this index corresponds to a surname that can only be found among past immigrants to Argentina, whereas a value of zero corresponds to surnames that can only be found among past immigrants to the US. The figure shows a strong association between the size of a migrant’s network in Argentina and the likelihood of moving there, suggesting a role for path dependence in explaining destination choices.

Figure 2

Conclusion

Argentina and the US both had open borders for European immigration and attracted Italians with comparable characteristics, but their assimilation experiences in each country were quite different. This finding raises doubts about the importance of immigration policy as a determinant of assimilation. Moreover, the fact that Italians moved in large numbers to both countries despite different assimilation experiences highlights the importance of path dependence in shaping migrants’ destination choices.

References

Baily, S L (2004), Immigrants in the lands of promise: Italians in Buenos Aires and New York City, 1870-1914, Cornell University Press.

Dillingham, W P (1911), Emigration conditions in Europe, US Government Printing Office.

Klein, H S (1983), “The Integration of Italian Immigrants into the United States and Argentina: A Comparative Analysis”, The American Historical Review: 306–329.

Martínez, A B (1910), “Censo general de población, edificación, comercio e industria de la ciudad de Buenos Aires”, Compañia sudaamericana de billetes de banco.

Pérez, S (2019), “Southern (American) Hospitality: Italians in Argentina and the US during the Age of Mass Migration”, NBER Working Paper 26127.