As part of the process of financial deepening, emerging economies’ governments increasingly rely on domestic sources of financing (IMF 2020). Brazil and Mexico are two early examples of this trend.1 Less well known is that almost 80% of all African sovereign bonds are issued domestically.2 Because domestic public debt markets constitute the backbone of domestic financial systems (CGFS 2007), sustainable public debt is paramount to domestic financial stability (Acemoğlu et al. 2022, Boone et al. 2022).

Against this background and despite the risk that the pandemic ends in a wave of sovereign defaults in both international and domestic sovereign debt markets (Kose et al. 2021), there is no systematic work focused on describing sovereign defaults involving domestically governed debt (IMF 2021). Given that debt jurisdiction (i) affects governments’ ability to restructure its debt (Gelpern and Panizza 2021), (ii) is key to shaping the restructuring process (Gulati and Weidemaier 2015), and (iii) affects the timing and conditions of market access (Chamon et al. 2018), this lack of data hinders policy work on the prevention and resolution of sovereign debt crises (IMF 2021).3

In a pair of papers (Erce et al. 2021a, 2021b), we bridge this gap by introducing a novel database that identifies sovereign defaults on domestic law-debt instruments held by private creditors.4 The database systematically records domestic sovereign defaults that are identified on the basis of whether the law governing the debt instruments was local.5

The database

Documenting domestic law defaults, their timing, size, and the details of the restructuring terms was challenging. We reviewed several and diverse sources, ranging from IMF official documents to local news articles. Our efforts led to the identification of 76 sovereign default and restructuring episodes in 52 countries. We built the database using a bottom-up approach, collecting information at the instrument level (default events) and aggregating it to obtain episode-level variables. These 76 default episodes are composed of 134 default events on different instruments (bonds, bank loans or deposits). The sample spans four decades, from 1980 to 2018, and covers events in all five continents.

The database collects finer details of each default event, such as its timing, the instrument and volume involved, as well as the terms and restructuring methods adopted. Where available, the database also reports net-present-value losses for creditors. Using our database, we draw various lessons.

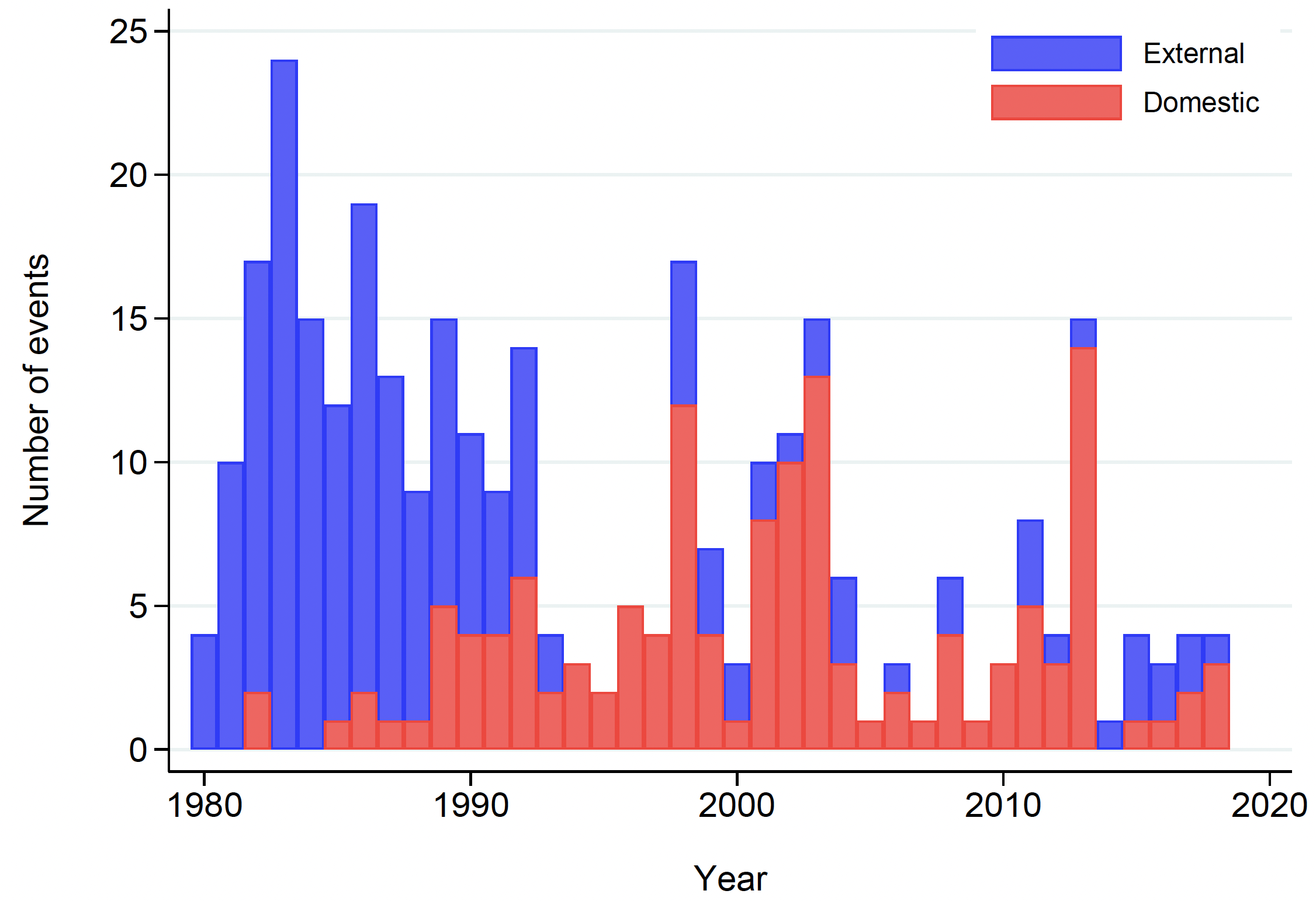

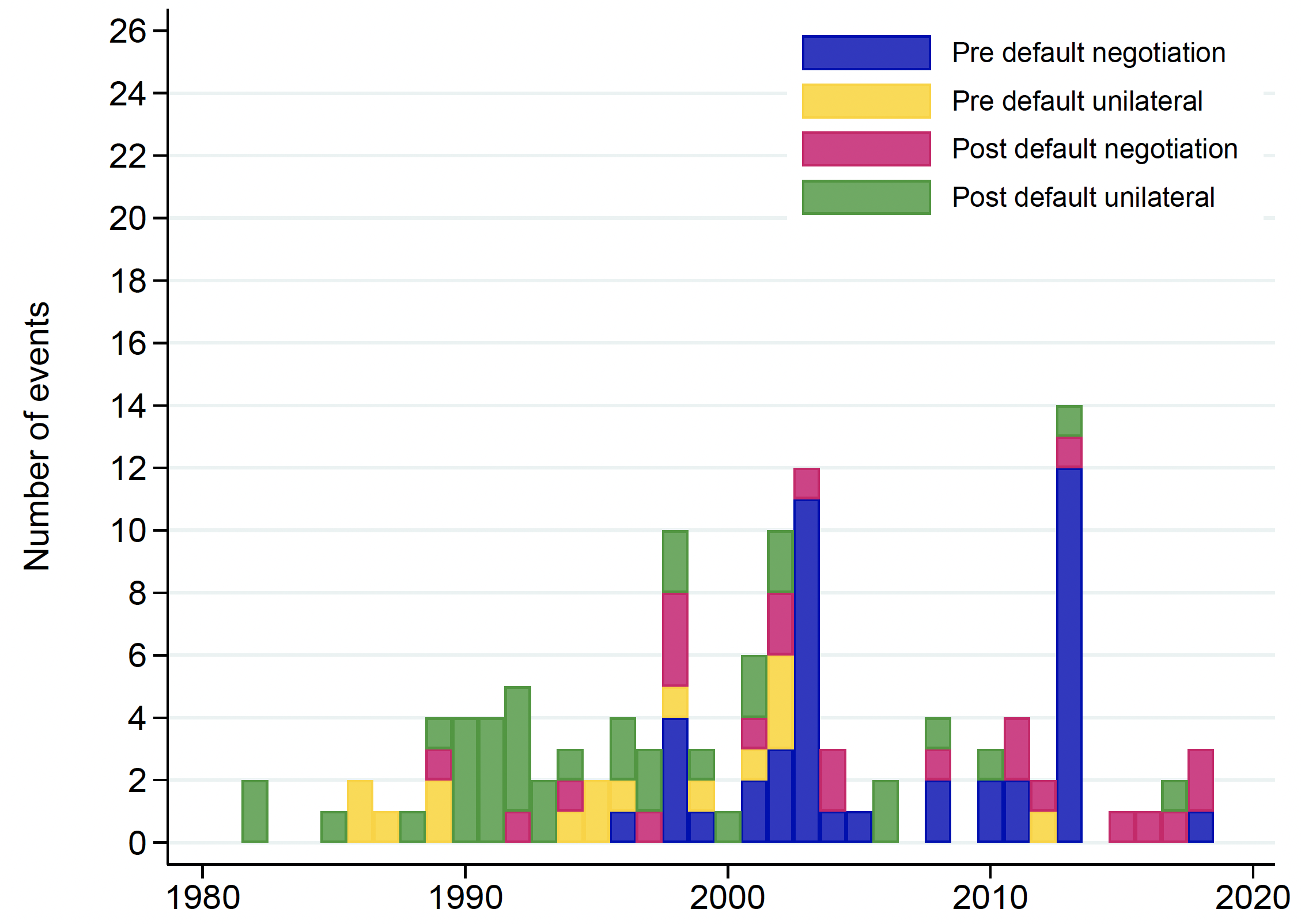

Domestic law defaults are a global increasingly frequent phenomenon. America and Africa are the continents where most restructurings have occurred. While domestic law defaults are more frequent in poor and middle-income countries, they also happen in advanced economies. Figure 1 combines our data with the database on foreign defaults maintained by Tamon Asonuma and Christoph Trebesch. Since the late 1990s domestic defaults have occurred more frequently than foreign ones. While in the 1980s around 10% of default episodes involved domestic law debt, in the 2000s, 70% of defaults episodes did. Moreover, governments operate selective defaults. In contrast, within the theoretical literature defaults are often modelled as affecting equally all creditors (Thaler 2021) or as discriminating in favour of domestic debt (Broner et al. 2010).

Figure 1 Domestic- and foreign-law defaults overtime

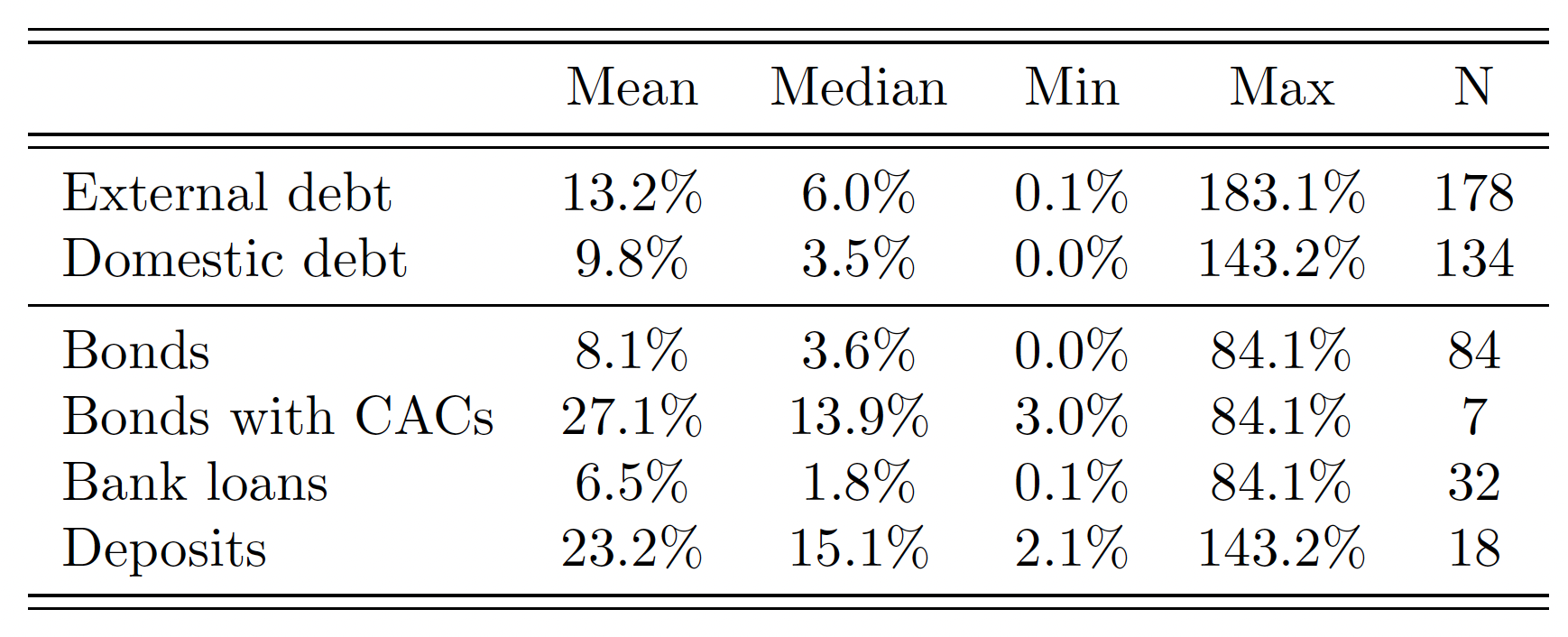

Defaults on bonded debt, which are the most common form of domestic law defaults, are increasing in size. While, as shown in Table 1, they are smaller than external ones, the median volume of domestic law bonds involved in recent restructuring episodes has reached 14% of GDP. Contrarily, defaults on bank loans and deposits are rare nowadays, likely reflecting the shift in governments’ funding sources.

Table 1 Volume of debt in default, by instrument (% of GDP)

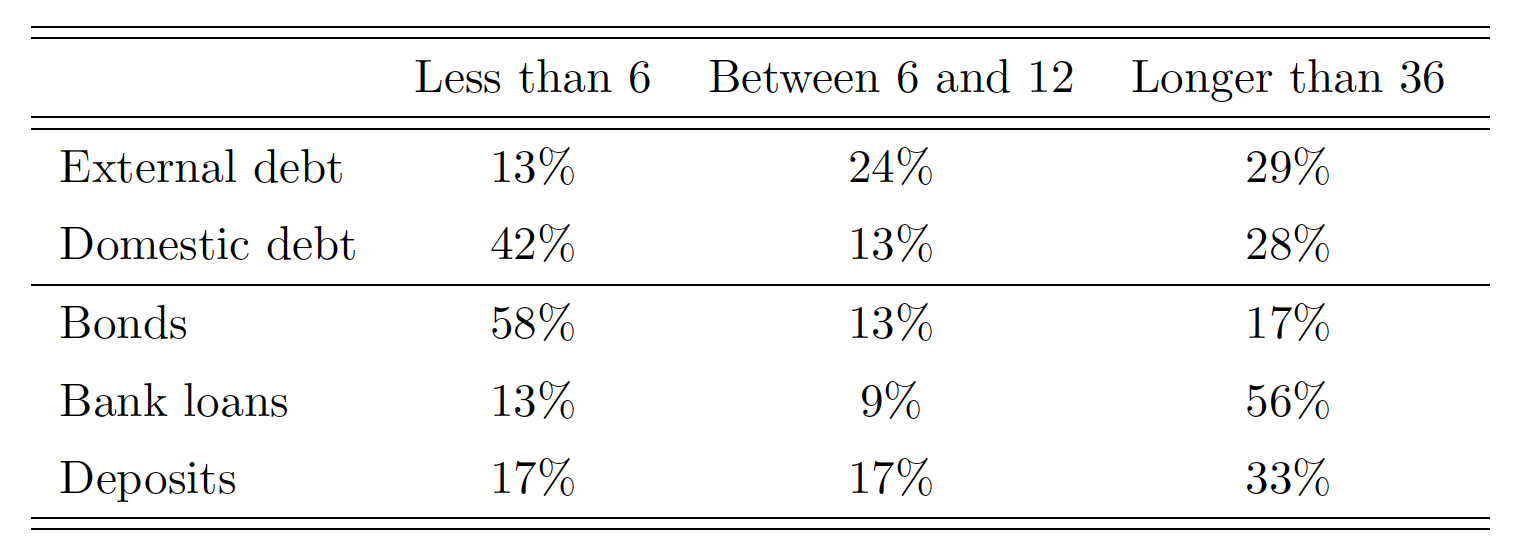

Domestic debt restructurings often proceed fast but can be significantly protracted. Table 2 shows that, in contrast to lengthier external default, around 40% of domestic law defaults were resolved within six months (this group includes events in which bonds included collective action clauses). Yet, a non-negligible fraction of episodes took a very long time to resolve – one third of them lasted more than three years and 6% lasted over 12 years.6

Table 2 Duration of domestic-law defaults (months)

Maturity extension is the most frequent form of restructuring. Maturity extensions feature in 75% of the episodes but vary greatly from case to case, ranging from just a few months to 50 years. Amendments to the coupon structure are also frequent, often involving a reduction of coupons and the exchange of variable-rate coupons for fixed-rate ones. Face value reductions are rare.

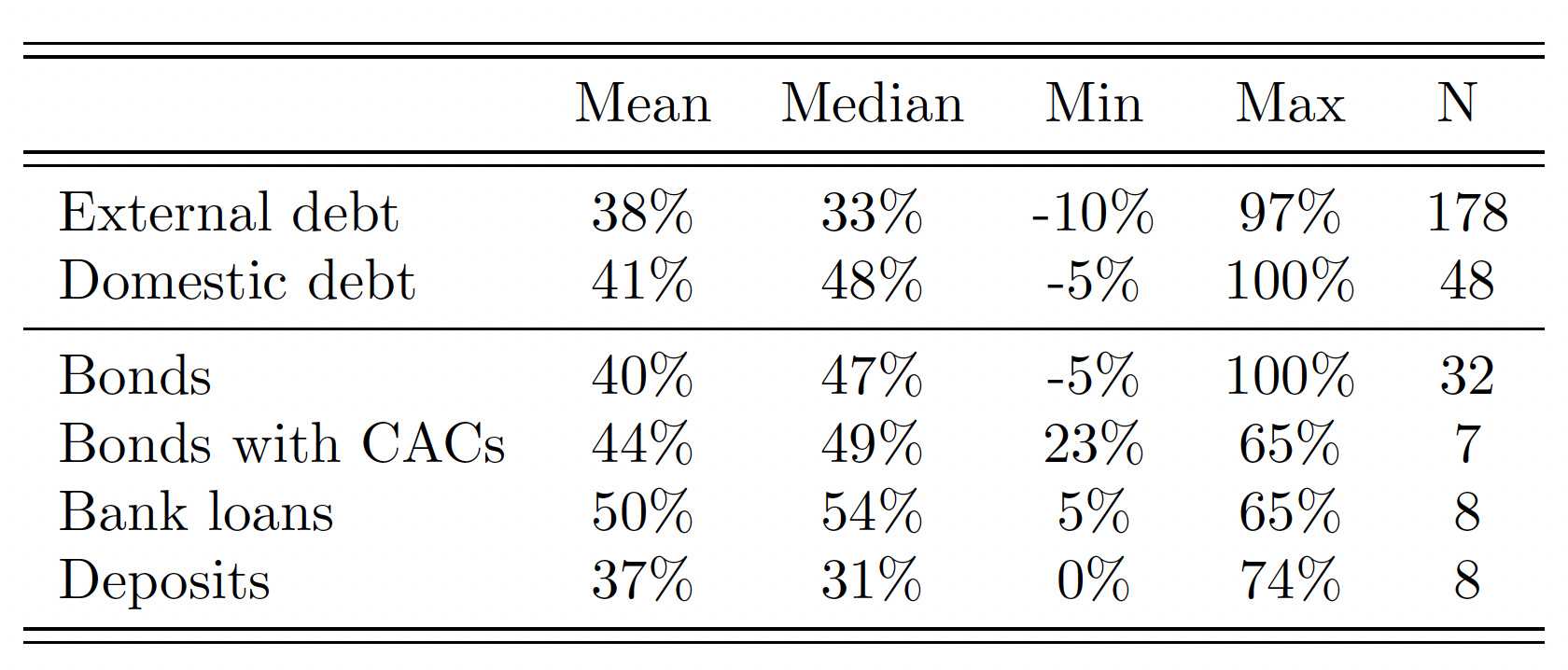

Median NPV losses are larger than those of external defaults. Table 3 reports summary statistics of NPV losses for different categories of domestic debt and for external defaults (as reported by Asonuma and Trebesch). Median NPV losses are larger following domestic law defaults. Losses are largest when the government defaults on bank loans, but also sizeable when CACs are used to restructure bonds.

Table 3 Creditors’ losses, by instrument in default

Unilateral post-default restructurings used to be the norm, but a preference for a negotiated pre-default approach is emerging. Since the 2000s, most domestic debt restructurings have occurred pre-default, with debtor governments adopting a cooperative approach toward creditors (see Figure 2). Governments were more aggressive in the 1980s and 1990s.

Figure 2 Pre- and post-default events and debtors’ stance

Conclusions

In a world with public debt growing alarmingly fast (Acemoğlu et al. 2022, Boone et al. 2022), the stylised facts drawn from our dataset convey important information and analytical material for policymakers in the need of finding policies to tackle debt distress. These same stylised facts can also inform quantitative work. Existing quantitative work including domestic debt markets has had a hard time calibrating the models.7 Our database documents multiple aspects of the restructuring process and provides a comprehensive set of statistics for the correct calibration of quantitative models of sovereign default featuring domestic debt.

Our data might be useful not only for lawyers and economists interested in the prevention and resolution of debt crises, but also for political scientists and sociologists interested on the interplay between domestic defaults and political cycles, institutional stability, social cohesion, or economic inequality, among other topics.

Authors’ note: The database described in this column can be accessed here. The views in this column are the authors and not those of the Federal Reserve Board or the European Stability Mechanism.

References

Acemoğlu, D, T Beck, M Obstfeld and Y Chui Park (2022), “Prospects of the global economy after Covid-19”, VoxEU.org, 28 February.

Asonuma, T and C Trebesch (2016), “Sovereign debt restructurings: pre-emptive or post-default”, Journal of European Economic Association 14(1).

Beers, D and P de Leon-Manlagnit (2019), “The BoC-BoE Sovereign Default Database: What’s New In 2019?”, Bank of England Working Paper No. 829.

Boone, L, J Fels, O Jordà, M Schularick and A M Taylor (2022), Debt: The eye of the storm, Geneva Report on the World Economy 24.

Broner, F, A Martin and J Ventura (2010), “Sovereign Risk and Secondary Markets”, American Economic Review 100(4).

Bulow, J and K S Rogoff (1989), “A Constant Recontracting Model of Sovereign Debt”, Journal of Political Economy 97(1).

CGFS – Committee on the Global Financial System Papers (2007), “Financial stability and local currency bond markets”, Committee on the Global Financial System Papers 28.

Chamon, M J Schumacher and C Trebesch (2018), “Foreign-Law Bonds: Can They Reduce Sovereign Borrowing Costs?”, Journal of International Economics 114(C).

Erce, A, E Mallucci and M Picarelli (2021a), “A Journey in the History of Sovereign Defaults on Domestic Law Public Debt”, European Stability Mechanism Working Paper No. 51.

Erce, A, E Mallucci and M Picarelli (2021b), “A Journey in the History of Sovereign Defaults on Domestic Law Public Debt – Sovereign Histories”, Departamento de Economía, Universidad Pública de Navarra, Working Paper No. 2108.

Gabor, D (2021), “The Liquidity and Sustainability Facility for African Bonds: Who Benefits?”, Eurodad Policy paper.

Graf von Luckner, C, J Meyer, C Reinhart and C Trebesch (2021), “External sovereign debt restructurings: Delay and replay”, VoxEU.org, 30 March.

Gulati, M and M Weidemaier (2015), “The Relevance of Law to Sovereign Debt”, Annual Review of Law and Social Science 11.

Gelpern, A and U Panizza (2021), “Emerging Market Debt Crises Economic and Legal Aspects”, mimeo.

IMF (2020), “The International Architecture for Resolving Sovereign Debt Involving Private Sector Creditors - Recent Developments, Challenges, and Reform Options”, IMF Policy Paper 2020/043.

IMF (2021), “Issues in Restructuring of Sovereign Domestic Debt”, IMF Policy Paper 2021/071.

Kose, M A, F Franziska Ohnsorge, C Carmen Reinhart and K Rogoff (2021), “Developing economy debt after the pandemic”, VoxEU.org, 3 November.

Reinhart, C and K Rogoff (2011), “The Forgotten History of Domestic Debt”, Economic Journal 121(552).

Thaler, D (2021), “Sovereign Default, Domestic Banks and Exclusion from International Capital Markets”, The Economic Journal 131(635).

Endnotes

1 Domestic debt accounted for 22% of Mexico’s public debt in 1995, and over 80% by 2010. In Brazil, it went from 54% to 90%.

2 In 2020, domestic bonds by African sovereigns reached US$500 billion and Eurobonds US$150 billion (Gabor 2021).

3 The importance of legal jurisdiction for the timing and form of the resolution of sovereign default was already noted by Kenneth Rogoff and Jeremy Bulow in their seminal 1989 paper at the Journal of Political Economy (Bulow and Rogoff 1989).

4 In Erce et al. (2021b), we present a collection of histories describing the finer detail of each default episode.

5 Our work extends and complements existing databases, such as Reinhart and Rogoff (2011), which also considers domestic debt, and Asonuma and Trebesch (2016), which focuses on external debt.

6 von Luckner et al. (2021) discuss the duration of default spells during foreign-law debt restructuring.

7 Hatchondo et al. (2016) discuss the difficulties in calibrating quantitative models of sovereign default on domestic debt.