The undersupply of subsidised childcare and the high costs of private arrangements are often pointed to as the main determinants of low female labour supply and of the slow return of women to work after motherhood. On these grounds a growing number of advanced economies are opting for highly subsidised childcare systems. Most recently, in Italy, the newly appointed government listed universal childcare provision amongst its priorities.

And yet, the existing evidence suggests that labour supply responses to reductions in the price of childcare may be weak and vary across countries, and even across individuals within the same country. Some studies, for example, have suggested that subsidised childcare may fail to stimulate maternal labour supply in countries with significant labour market slack (Nollenberger and Rodriguez-Planas 2015) or where alternative (non-parental) arrangements are widely diffused (Havnes and Mogstad 2011, Goux and Maurin 2010, Fitzpatrick, 2010). And looking beyond female labour supply reveals that universal childcare does not necessarily impact positively on children’s development, with the final effect mainly depending on the quality of alternative (parental or non-parental) available arrangements. While some studies have shown that universal (high-quality) childcare provision benefits children from lower socio-economic background (Havnes and Mogstad 2015, Felfe and Lalive 2018), others have argued that the effect might be instead negative for children from more affluent families (Baker et al.2008, Lefebvre and Merrigan 2008).

When thinking about both female labour supply and children’s development it is therefore unclear whether providing universal childcare represents a ‘double dividend’ policy, entails a trade-off between the two outcomes, or even produces none of the desired effects. In the light of the high costs involved, an expansion of subsidised childcare should therefore be conditional on a comprehensive evaluation of its effects.

In a recent paper, we estimate the impact of universal childcare provision on both maternal labour supply and children’s development (Carta and Rizzica 2018). In doing so, we take advantage of an Italian reform that lowered the age of entry into kindergarten from three to two years old. Given the Italian institutional setting, this shift effectively implied an expansion of universal childcare provision.

The institutional setting and the research design

In Italy, formal childcare for children under six is provided through two types of arrangements: nurseries for 0-2 year olds, and kindergartens for 3-5 year olds. While these arrangements are comparable in terms of opening hours and overall quality (as measured by teacher-to-children ratio and the educational requirements for teachers), kindergartens are significantly less expensive (they are more highly subsidised so that their cost is around 70% lower than that of nurseries) and cover almost the entire reference population (whereas coverage for children aged 0-2 is just above 20%).

Until 2003, children were allowed to start kindergarten at age two only if they turned three by the end of December of the school year. In 2003, a law extended the opportunity to enrol into kindergarten to children born by 30 April of the school year. Under the previous rules these children would have waited one extra year to start kindergarten, in the meantime attending nurseries or being looked after by parents or in other non-formal arrangements. In the same way, the law established that children turning six by 30 April could enter primary school one year earlier. While the cut-off date remained constant for primary school admission, it instead changed several times for early kindergarten, the 30 April rule becoming effective only in 2009. Early access to kindergarten was widely used – about 40% of the eligible children actually anticipated entry.

Our research design exploits the fact that the policy exogenously extended universal childcare provision to a group of families whose only requirement was that their child’s date of birth preceded a given cut-off date. By comparing mothers of children born shortly before and after the given cut-off, we can thus identify the causal effect of the policy on maternal labour supply. Identification relies on the assumption that mothers of children in the two groups are comparable in terms of observable and unobservable characteristics. To recover the causal effects on children’s outcomes, we further exploit the changes in the eligibility rule that occurred between 2003 and 2009. This allows us to isolate the effect of early kindergarten from that of being eligible for entering primary school earlier.

Findings

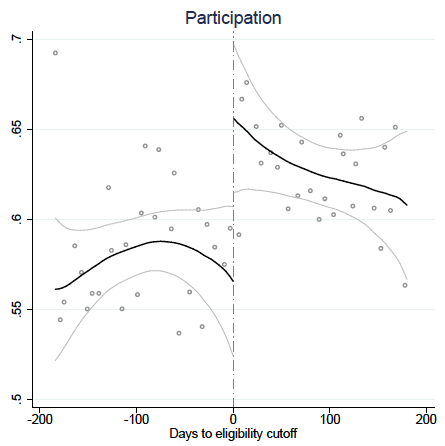

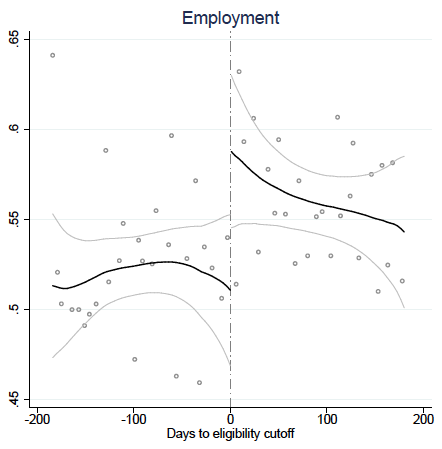

Drawing on the Italian Labour Force Survey data, we estimate sizeable positive effects of early kindergarten on labour market outcomes. The labour market participation rate of mothers of eligible children increased by about 6% and their employment rate by about 5%. The effect on employment was not just mechanically driven by the higher influx of mothers in the labour market looking for a job, but also by changes in their acceptance rule, as we estimate a significant reduction of their reservation wage. The effects were concentrated among higher income families who enjoyed a larger discount in switching from nursey to early kindergarten.1

Figure 1 Effects of early kindergarten eligibility on mothers' labour supply

Note: The horizontal axis shows the distance from the cut-off date of birth. Observations to the right of the cut-off correspond to children who were born before the cut-off (eligible for early kindergarten), observations to the left of the cut-off correspond to children who were born after the cut-off date (non-eligible). The graphs show the estimated discontinuity for local linear regression approximation with triangular Kernel weights and a bandwidth of 120 days. The grey lines are the estimated 95% level confidence intervals. The dots of the underlying scatterplots show the mean outcome in bins of one week's width.

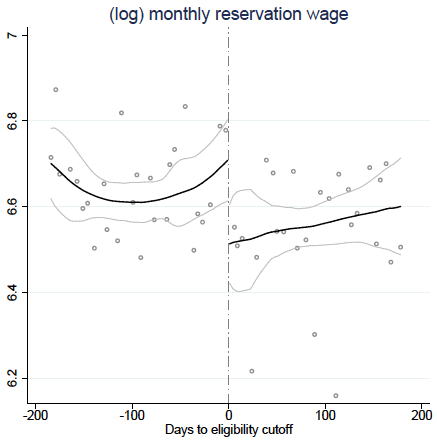

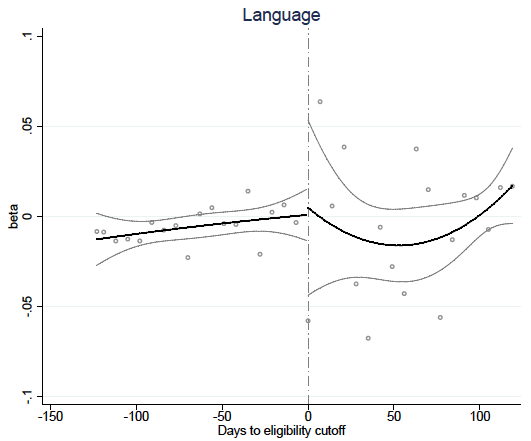

As for children outcomes, we use a large administrative dataset on Italian students’ test scores administered by the National Institute for the Evaluation of the Education System. Data are only collected starting in the second grade, so our focus is on the medium-run effects of the policy. We do not find any effect of early kindergarten on children’s test scores in language and maths, irrespective of their family background. This result is particularly reassuring because early kindergarten was mostly used by children from more affluent families, whom previous works found to be negatively affected by the introduction of universal childcare (Lefebvre and Merrigan 2008).

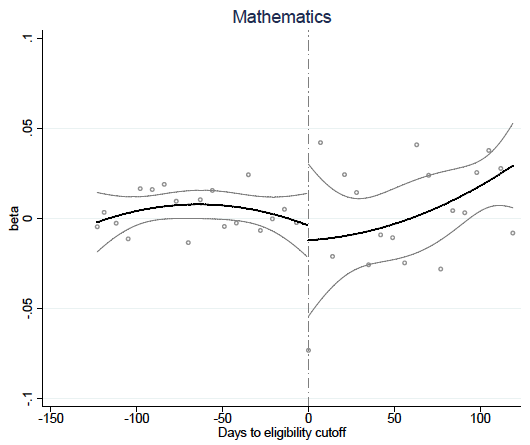

Figure 2 Effects of early kindergarten eligibility on children’s test scores at grade 2

Note: The horizontal axis shows the distance from the cut-off date of birth. Observations to the right of the cut-off correspond to children who were born before the cut-off (eligible for early kindergarten), observations to the left of the cut-off correspond to children who were born after the cut-off date (non-eligible). On the vertical axis, beta is the difference between average scores for cohorts that were eligible for both early school and early kindergarten and cohorts that were only eligible for early school. The discontinuities thus show the treatment effect of eligibility for early kindergarten. The specification employed is a second order polynomial approximation.The dots of the underlying scatterplots show the mean outcome in bins of one week's width.

Policy implications

Our results provide support for policymakers promoting the extension of affordable, good-quality early childcare provision in countries that currently have low coverage and where female labour supply is low. Yet, as the implementation of universal childcare programmes is costly, our findings can also be used to inform the policymaker on the design of alternative, more cost-effective policies.

A first alternative would be to condition the provision of subsidised childcare on mothers’ employment status. Unlike the systems of conditional subsidies that are currently in place in the US and the UK for example, a more effective scheme should address not only mothers who are employed but also those who are actively searching for a job. Indeed, our results showed that mothers significantly increased their job search effort when given the chance to use early kindergarten. Therefore excluding them from the subsidy would lower the benefits of the policy in terms of labour force participation, especially in labour markets with high frictions and where labour demand is slack.

Second, the fact that access to subsidised childcare induced a significant drop in mothers’ reservation wages suggests that a similar policy indirectly benefits employers by reducing their labour costs. On these grounds, the policymaker may prefer to opt for a scheme that induces firms to internalise this positive externality by promoting the development of corporate welfare. However, at the same time it would be necessary to set quality requirements for on-site corporate childcare in order to avoid undesired effects on children’s outcomes.

Authors' note: The views expressed here are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of the Bank of Italy.

References

Baker, M, J Gruber, and K Milligan (2008), “Universal child care, maternal labor supply, and family well-being”, Journal of Political Economy 116(4): 709-745.

Carta, F, and L Rizzica (2018), “Early kindergarten, maternal labor supply and children’s outcomes: Evidence from Italy”, Journal of Public Economics 158: 79-102.

Felfe, C, and R Lalive (2018), “Does early child care affect children’s development?”, Journal of Public Economics 159: 33-53.

Fitzpatrick, M D (2010), “Preschoolers enrolled and mothers at work? The effects of universal prekindergarten”, Journal of Labor Economics 28(1): 51-85.

Goux, D, and E Maurin (2010), “Public school availability for two-year olds and mothers’ labour supply”, Labour Economics 17(6): 951-962.

Havnes, T, and M Mogstad (2011), “Money for nothing? Universal child care and maternal employment”, Journal of Public Economics 95(11-12): 1455-1465.

Havnes, T, and M Mogstad (2015), “Is universal child care leveling the playing field?”, Journal of Public Economics 127: 100-114.

Lefebvre, P, and P Merrigan (2008), “Child-care policy and the labor supply of mothers with young children: A natural experiment from Canada”, Journal of Labor Economics 26(3): 519-548.

Nollenberger, N, and N Rodríguez-Planas (2015), “Full-time universal childcare in a context of low maternal employment: Quasi-experimental evidence from Spain”, Labour Economics 36: 124-136.

Endnotes

[1] Fee schedules are modulated in such a way that low income families pay approximately the same amount for nurseries and kindergartens, while more affluent families pay significantly more for nurseries.