Editors' note: This column is taken from a new CEPR eBook, Supporting Ukraine: More critical than ever, available to download here.

Immediately following the Russian invasion of Ukraine, an influential view in German policy circles held that, while it was important to support Ukraine, an embargo on Russian energy exports should be off the table because the economic costs would be enormous. Chancellor Olaf Scholz warned of “the loss of millions of jobs” in the event that Russian energy were cut off and vice-chancellor Robert Habeck warned of “mass unemployment and poverty”. These warnings were in line with those by industry leaders. For example, the CEO of BASF, Martin Brudermüller, predicted that a cut-off from Russian gas “could bring the German economy into its worst crisis since the end of World War II and destroy our prosperity”, adding "Do we knowingly want to destroy our entire economy?"

At least in part due to these apocalyptic predictions, Western countries opted for a cautious approach to sanctioning Russian hydrocarbon exports and such sanctions did not begin in earnest until the EU crude oil embargo took effect in December 2022, i.e. almost ten months after the start of the war. Sanctions on gas exports were noticeably absent from any sanctions packages. But already in the spring and summer of 2022, Putin started weaponising Russia’s gas supplies, first substantially cutting deliveries in June in particular through the Nord Stream 1 pipeline and then completely halting them in September, effectively resulting in the same outcome as a gas embargo.

How Western economies adapted to Putin’s energy war

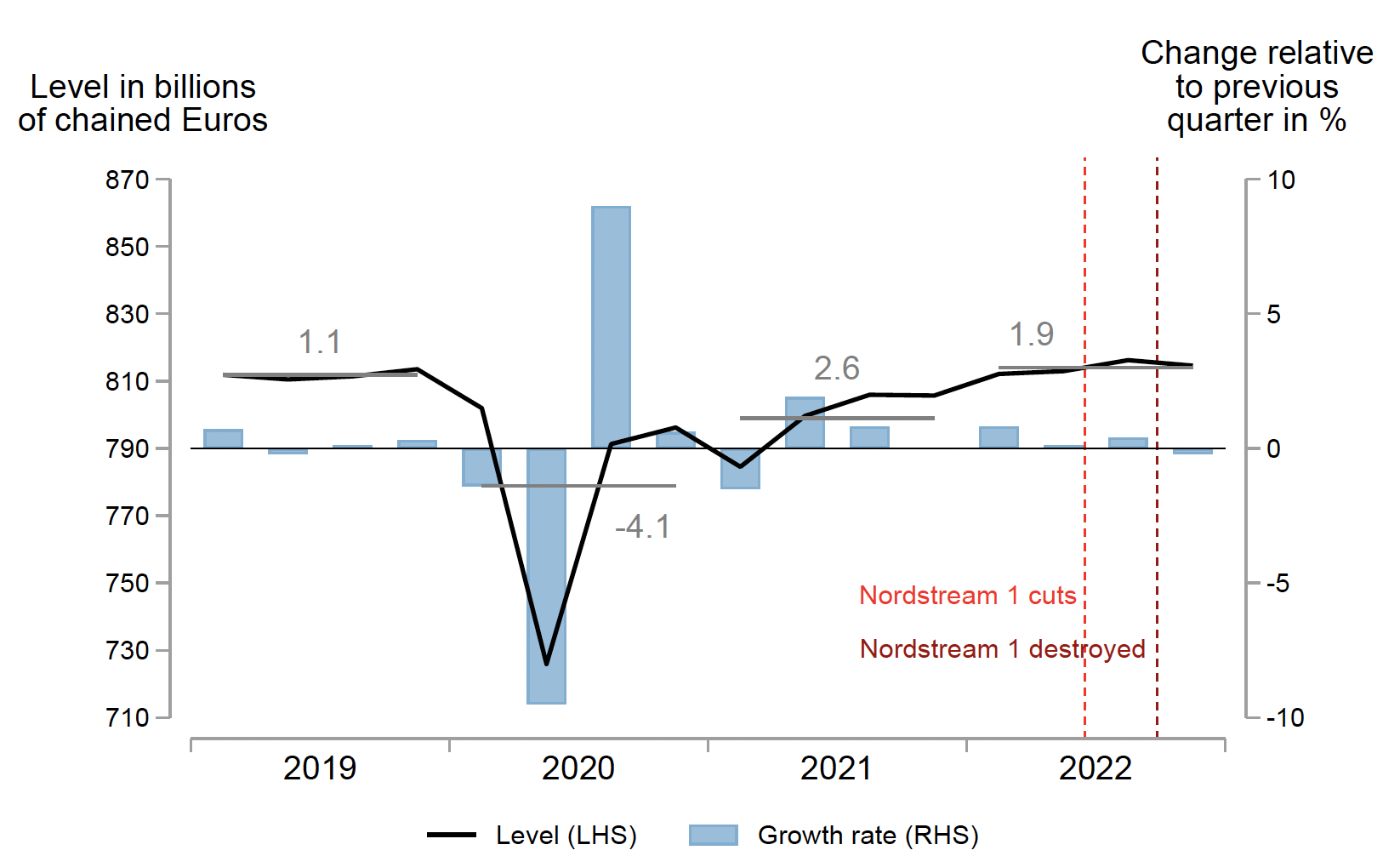

As we now know, in the wake of the Russian gas cut-off, European economies did not see the type of collapse predicted by German politicians and industry representatives. As an example, Figure 1 plots the evolution of German GDP since 2019.

Figure 1 Real GDP in Germany

Note: Seasonally and calendar adjusted.

A large drop in economic activity is visible in 2020 during the Covid pandemic. However, there is no (even remotely) comparable drop following the cuts in gas deliveries marked by the two red vertical lines: Germany’s GDP grew in all quarters of 2022 except Q4, when it declined by 0.2%. Of course, from the time-series it is impossible to infer the counterfactual of economic activity would have looked like without the gas cut-off. But what is clear is that the truly apocalyptic scenarios have not come true.

Why did Putin’s energy weapon fail to fire? There is a multitude of factors but the most important among these was energy demand reduction and substitution by European households and firms. For example, as of January 2023, EU-wide natural gas consumption was a striking 25% below its 2019–2021 average, with similarly large reductions in many individual member countries (McWilliams and Zachmann 2023). Alternative supplies available on the world market also played an important role. The large observed demand reductions are in line with predictions of both basic economic theory as well as more complex multi-sector models (Bachmann et al. 2022). Thus, both our experience and our models suggest that sanctioning Russia has been much less costly than many predicted.

“Each euro of Russian energy exports contributes exactly one euro to the war”

The main rationale for sanctioning Russian energy exports has always been simple, namely, that these exports represent an important source of fiscal revenues for the Russian state, money that is then used to wage war in Ukraine. As Oleg Itskhoki has put it, "each marginal euro received [by Russia] from energy exports to Europe contributes exactly one euro to the war, as simple as that".

Opponents of the energy embargo idea have often argued that this effect is absent because the Russian government can print its own money and therefore does not need to rely on export revenues. My favourite rebuttal of this argument is due to Hanno Lustig: “Suppose we did a helicopter drop of dollars in Red Square in Moscow. If no one bothers to pick them up, then export curbs are irrelevant. Not a likely outcome.”

Or, as Bachmann puts it in his contribution to this volume: “This is an example of how modern monetary theory-like thinking can literally cost lives.”

The delayed and cautious implementation of energy sanctions by Western countries therefore contributed to Russia earning record export revenues in 2022. This in turn likely contributed to Russia’s ability to wage war in Ukraine. For example, Babina et al. (2023) argue that, even though the EU oil embargo only came in effect in December 2022, it has already materially affected Russian export revenues and, furthermore, that an earlier introduction of the EU oil embargo and/or G7 price cap in the immediate aftermath of the invasion could have reduced Russia’s oil export earnings by up to $50 billion, or about one third.

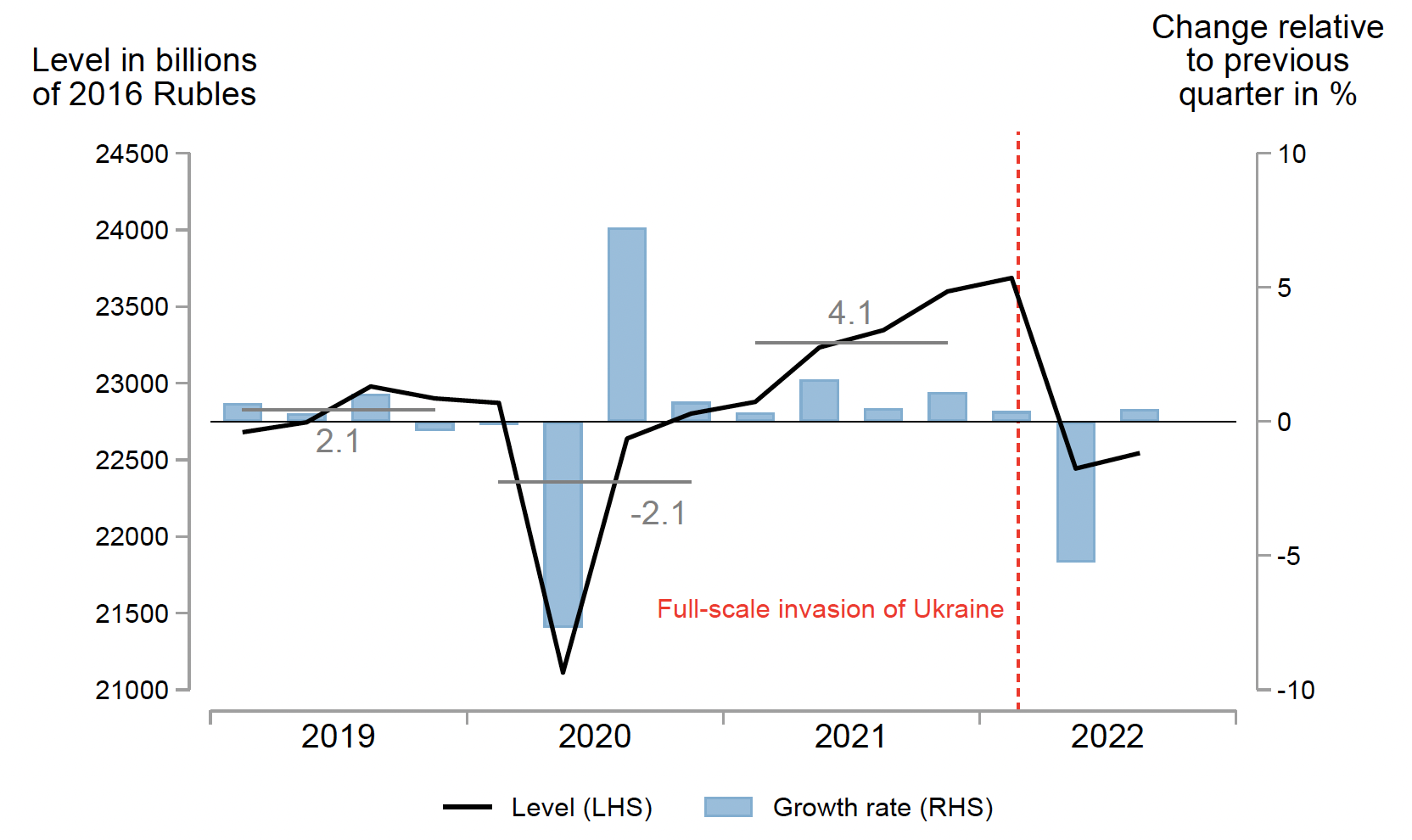

Related, there is evidence that other forms of sanctions, in particular sanctions on Russian imports did play an important role in weakening the Russian economy and state. For example, Figure 2 plots the evolution of real GDP in Russia as reported in the official Russian national accounting statistics (Rosstat 2022), the same series that was also used by Bachmann (2023).

Figure 2 Real GDP in Russia

Note: Seasonally adjusted.

The figure shows a very sizable drop in Russian GDP of around 5% that begins right after the full-scale invasion of Ukraine and the imposition of sanctions. As noted by Bachmann (2023), aggregate consumer spending fell even more, by up to 7.5%. Note in particular how the size of the drop in 2022 compares to the barely noticeable dip for Germany in Figure 1. Also see the contribution by Schmith and Sakhno in this volume, who use an alternative tracker of Russian economic activity which points to a recession that is deepening further than the official statistics suggest.

Options for tightening energy sanctions on Russia

On the one hand, sanctions and Putin’s ensuing energy warfare have been much less costly for Western economies than many predicted. On the other hand, it remains true that Russian hydrocarbon exports fund the war in Ukraine. This suggests that the West should look for ways to further tighten the sanctions regime on Russian energy exports.

I here briefly discuss possible strategies for achieving this, mostly drawing on work from two sources: Babina et al. (2023) as well as a number of papers written by the Yermak-McFaul International Working Group on Russian Sanctions. Given the existing sanctions infrastructure, in particular the EU oil embargo and G7 oil price cap, some natural ways of tightening sanctions are:

- improving the enforcement of the G7 oil price cap, for example via audits of attestations regarding compliance with the price cap (Babina et al. 2023);

- lowering the oil price cap;

- implementing a cap on oil products (and not just crude oil) (International Working Group on Russian Sanctions 2023).

Other options (like taxes and tariffs) were laid out by International Working Group on Russian Sanctions (2023) but may be less feasible politically. In weighing these options, we need to remind ourselves that the costs of tightening sanctions will likely be moderate but that each euro less paid to Russia is one less euro for the war in Ukraine.

References

Babina, T, B Hilgenstock, O Itskhoki, M Mironov, and E Ribakova (2023), “Assessing the Impact of International Sanctions on Russian Oil Exports”.

Bachmann, R (2023), “Why it is imperative to help Ukraine”, VoxEU.org, 17 February.

Bachmann, R, D Baqaee, C Bayer, M Kuhn, B Moll, A Peichl, K Pittel, M Schularick (2002), “What if? The Economic Effects for Germany of a Stop of Energy Imports from Russia”, ECONtribute Policy Brief 28/2022.

International Working Group on Russian Sanctions (2022a), “Energy Sanctions Roadmap: Recommendations for Sanctions against the Russian Federation”.

International Working Group on Russian Sanctions (2022b), “Implementation of the Oil Price Cap”.

International Working Group on Russian Sanctions (2023), “Introduction of a Low Price Cap on Russian Oil Products”.

Itskhoki, O and D Mukhin (2022), “Sanctions and the Exchange Rate”, VoxEU.org, 16 May.

McWilliams, B and G Zachmann (2023), “European natural gas demand tracker”, Bruegel.

Rosstat (2022), GDP statistics, Sheet 9, 29 December.

Schmith, A and H Sakhno (2023), “The recession in Russia deepens: Evidence from an alternative tracker of domestic economic activity”, VoxEU.org, 14 February.