As WTO trade ministers gather next week in Geneva – one full year after the financial crisis exploded into the global economic crisis – the full impact of the crisis on African countries is yet to be quantified, and while global economic prospects are improving, it is too early to talk of a genuine recovery.

In February, the African Economic Outlook 2009 projected that real GDP growth in Africa for 2009 would decline drastically to 2.3%, barely half that of the preceding two years. The growth rate has since been downgraded as the crisis continues to take its toll on African economies; the latest forecasts predict growth of 2% for the continent. The growth outlook for 2010 is more optimistic (3.9%), but still falls short of the 6.1% growth achieved prior to the crisis.

The Great Recession and the great trade collapse

This sharp economic downturn worldwide has led to an immense contraction in international trade.

- African export volume growth is expected to decrease to 4% in 2009, from a buoyant rate of 11% in 2008, translating into a 45% loss in export value.1

- The biggest slump is for middle-income countries, as their exports depend heavily on commodities (e.g. oil and precious metals) whose prices and demand has been severely hit; their manufactures exports have also suffered.

- Oil and precious metals were affected mainly by a slump in global commodity prices, while manufactures suffered due to contraction in demand as the real sector in key markets shrunk.

- Low-income countries show some resilience, considering that their exports are in “soft” commodities – such as tea, coffee, etc. – which did not experience a drastic decline in prices or demand on the global market.

This chapter discusses the trade situation in Africa in key global markets and the impact of the global economic crisis on different income groups and sectors. In addition to market access issues, the paper highlights the importance of initiatives such as “Aid for Trade” in helping African countries realize the full gains from trade liberalization.

Trade collapse in the midst of the financial crisis in major markets

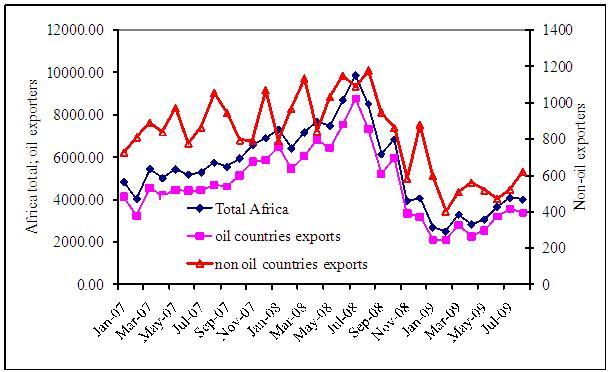

The slowdown in major trading partners, coupled with Africa's undiversified exports has severely affected the continent’s trade. This is exemplified by the drastic fall in exports to the US, which fell by more than 50% between August 2008 and August 2009, from $8,525 million to $4,017 million (Figure 1).

Figure 1 African exports to the US, January 2007-August 2009 ($ million)

Source: US Department of Commerce.

The fall in US demand for African products has especially affected oil exporters (Nigeria, Angola, Chad, Equatorial Guinea, Republic of Congo, Gabon, Côte d’Ivoire, Cameroon, and the Democratic Republic of Congo). The collapse in oil exports accounts for the sharp swing in growth rates in these countries, with Angola, for example, going from a double digit growth rate over the past years, to a projected zero growth in 2009.

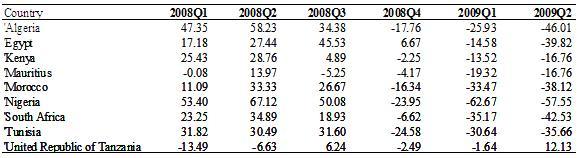

Table 1 presents the trends in exports from middle-income African countries to the main global markets (European Union, US, Japan and China). The key points are:

- Algeria, Egypt, Morocco, Nigeria and South Africa experienced the sharpest deterioration in exports, starting in the fourth quarter of 2008, when the impact of the financial crisis on the real sector became evident.

- South Africa suffered a sharp decline in manufacturing products and precious metals, such as gold and platinum. With the increases in the price of gold and platinum of around 14% and 19% respectively, in the first quarter of 2009, the sector has started showing signs of early recovery.

- As an exporter of mainly agricultural products, Tanzania was spared, with an increase in exports of 12.13% in the second quarter of 2009.,

Table 1 Middle-income countries' exports to EU, US, Japan & China, 2007Q1 to 2009Q2 (% change)

Source: ITC calculations based on National Government Statistics

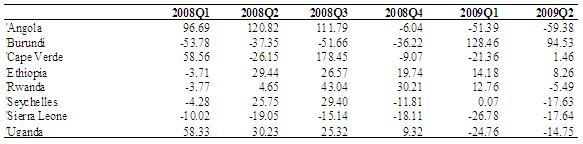

For low-income countries the largest contractions were experienced in Angola, Rwanda, the Seychelles, Sierra Leone and Uganda. Table 2 shows that:

- Oil importing countries, such as Angola, were hit the most compared to countries that are mainly exporters of agricultural products.

- Angola’s exports (mainly oil) declined by 59.3% in the second quarter of 2009.

- Countries such as Burundi and, to some extent, Ethiopia, experienced substantial growth in exports during the financial crisis, with exports in the second quarter of 2009 growing at 94.5% and 8.3% respectively.

Table 2 Lower income countries' exports to the EU, US, Japan and China, 2007 Q1 to 2009 Q2 (% change)

Source: ITC calculations based on National Government Statistics.

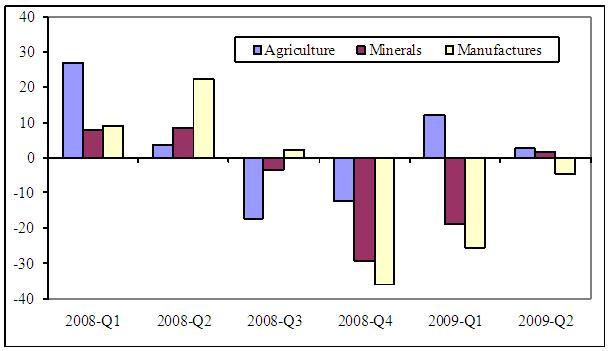

Figure 2 shows that the impact on African exports becomes evident as global markets entered a recession in 2008 Q3. Not surprisingly, manufactured goods from Africa contracted by 36% as consumers’ demand shrunk, due to declining incomes and expectations of a worsening global economic condition. Likewise, mining exports also followed with a decline of 25%. The impact lessens in the second quarter of 2009, with mineral exports showing resilience as the price started to rebound for key products such as oil and gold. The agricultural sector was the least directly affected by the financial crisis.

Figure 2 Exports of African countries to major global markets

Source: ITC calculations based on National Government Statistics

The DDA

The tentative recovery of African trade should not distract global leaders from the task of locking in long-term progress by completing the Doha Development Agenda (DDA).

The DDA is an opportunity to improve global growth prospects from which all economies and societies can benefit. Most importantly, trade negotiations offer a chance for African countries to catch up with their competitors by:

- Locking-in domestic or unilateral reforms; and

- Getting the advanced economies to open up to their markets, thus levelling the playing field for Africa with respect to its key competitors.

Failure of the DDA to meet its objectives will not only undermine the importance of the WTO, but will also jeopardise the trade and growth prospects of developing economies; if this happens, Africa – with its reliance and commodity exports – will be amongst the biggest losers.

As agricultural issues are central to the successful completion of the DDA, Africa should continue to push for more progress on agriculture’s three main contentious issues: (i) agricultural tariffs; (ii) trade distorting, domestic support provided by developed countries to their farmers; and (iii) export subsidies. The leadership of developed countries is critical in ensuring progress on these issues.

Gains from a Doha success

The economic gains that Sub-Saharan Africa stands to reap from the DDA are large – although their exact magnitude remains a conjecture. Studies show that:

- Sub-Saharan Africa would see a modest $5,000 million increase in merchandise trade (some 1.1% of the region’s GDP);

- Agriculture would account for 78% of this total gain;

- African cotton farmers are likely to boost their exports by $1,900 million.

A more ambitious target of full merchandise trade liberalisation, with a supportive domestic policy environment, is estimated to result in gains of approximately 5% of income in developing countries, which would lift some 300 million people out of poverty by 2015.

Should they accrue, such benefits will be unmatched by those from all other forms of international economic cooperation, including debt relief and official development assistance. It is therefore critical that developed countries take a leadership role and commit to ensuring that these potential gains are realized. The DDA must be concluded.

Going beyond market access: Championing the Aid for Trade initiative

In this current economic environment, the Doha Round, if concluded on time, will provide an opportunity for African countries to make strategic decisions to boost economic performance, which is critical for recovery.

It is important, however, for the international community to recognize that market access alone is not enough; supply-side constraints need to be addressed in order to enable developing countries, especially Least-Developed Countries (LDCs), to take advantage of trade opportunities. Coordinated efforts by all the key stakeholders to identify and address supply-side constraints – especially both “hard and soft infrastructure”, such as roads, ports, rail networks, one-stop border posts, harmonisation of custom systems, training of customs officials and simplification of regulations and documentation – are of utmost importance. These reforms will require adjustment financing, for which countries rely heavily on Aid for Trade.

Aid for Trade is an initiative that has emerged from the Doha Round of trade negotiations. The initiative, however, is not dependent on a successful conclusion of the Doha Round. It is a mechanism through which the development community can assist developing countries, especially LDCs, to take advantage of trade opportunities by enhancing market access and helping these countries alleviate structural supply-side constraints.

Under the leadership of the WTO, significant progress has been made in mobilizing Aid for Trade, with the clear commitment of the international community. According to the Aid for Trade at a Glance 2009 by the OECD, Aid for Trade commitments increased to $25.4 billion, a rise of $4.3 billion from the baseline period 2002-2005. However, it is important that Aid for Trade be not only driven by donors and the international community, but that African countries remain proactive in designing a coherent set of policy options targeted toward their own development objectives. The Aid for Trade initiative must also complement and strengthen Africa’s regional integration efforts, particularly through an increase in intra-African trade. This leaves a clear role for regional institutions, such as the African Development Bank, the African Union Commission and the United Nations Economic Commission for Africa, as well as regional economic communities (RECs), to support the regional integration agenda.

Regional distribution of Aid for Trade

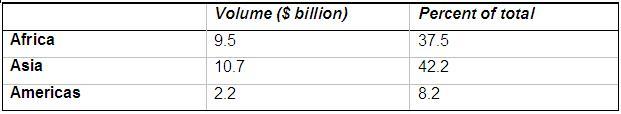

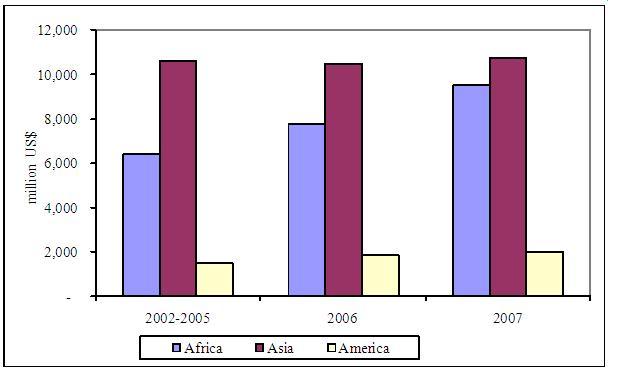

Aid for Trade to Africa stood at $9.5 billion (37.5% of total Aid for Trade) in 2007, while commitments to Asia and the Americas amounted to $10.7 billion (42.2%) and $2.2 billion (8%), respectively (Table 3). For Africa, this represents an increase of 23% from 2006 and 49% from the baseline of 2002-2005 (Figure 3), which is the largest increase relative to other regions. The 5 major recipients of Aid for Trade in Africa in 2007 were Kenya, Ghana, Mali, Uganda and Egypt. In terms of sector distribution of Aid for Trade flows, economic infrastructure dominated, accounting for 62% of total flows to Africa (Figure 4). Other areas that the African Development Bank has financed include building productive capacity, agriculture in particular, as well as trade policy and regulation.

Table 3. Regional distribution of Aid for Trade ($ and % of total), 2007

Source: Calculations based on OECD Data

Figure 3. Aid for Trade by region, 2000- 2007 ($ million)

Source: Calculations based on OECD Data

Figure 4. Sectoral distribution of Aid for Trade flows in Africa

Source: Authors’ calculations based on OECD data

The role of the African Development Bank in the Aid for Trade agenda

The African Development Bank (ADB) also recognizes that market access opportunities in the global market have the potential to offer African countries long-term sustainable income, which can be used to increase unemployment, boost economic growth and reduce poverty. At the same time, the ADB acknowledges that any form of trade liberalization through tariff reduction can be expected to trigger a restructuring of activities that may lead to, for example, loss of fiscal revenue, loss of competitiveness and changes in the distribution of employment. It is therefore the responsibility of the ADB and policy makers to anticipate these potentially negative economic and social outcomes, thereby making the Aid for Trade initiative an important instrument in addressing some of these undesirable effects. The ADB, in particular, through its increased focus on both physical infrastructure and private sector development, recognizes its important financing role in Aid for Trade.

The African Development Bank believes it is essential for African countries to get a good trade deal in the Doha Round, rather than depend on any adjustment funds they may be able to secure in the form of Aid for Trade, in the event of a bad outcome. Therefore, the ADB’s main obligation is to harness the areas where opportunities for African countries are most expected. This includes supporting capacity building in trade negotiations as well as the critical trade policy areas, such as rationalizing the best tariff structure that accommodates Doha and other trade agendas.

In addition, the ADB is supporting trade-related infrastructure (i.e. transport, energy, logistics), financial and capital market development, as well as other areas in order to reduce transaction costs. Promoting improvements in infrastructure and the business environment is opening up opportunities for the foreign private sector, both in terms of trade and of investment. After all, it is the private sector that trades. According to the Aid for Trade data reported by the ADB, new commitments for infrastructure, the largest sector in terms of contribution, amounted to $232 million in 2006 and $831 million in 2007, accounting for 54% and 78% of the ADB’s total Aid for Trade contribution. As part of its commitment to the Aid for Trade agenda in the continent, the ADB pledged $600 million to support infrastructure and other related activities on the North-South Corridor during the April 2009 meeting in Zambia, which was convened by the East African Community (EAC), the Common Market for East and Southern Africa (COMESA) and the Southern Africa Development Community (SADC). The ADB is anticipating that this important initiative will be replicated in other regions in Africa. The ADB also contributes to other categories of Aid for Trade, including trade policy and regulation, adjustment and capacity building.

Furthermore, in times of economic distress, institutions such as the ADB are called upon to assist their regional member countries. At the height of the global financial crisis in 2009 the ADB responded swiftly and approved the Trade Finance Initiative to the amount of $1billion in support of trade; $500 million came in the form of lines of credit to African financial institutions to support trade finance operations; $500 million came in the form of the Global Trade Liquidity Programme (which was jointly implemented with other global financial institutions). Trade finance also falls under Aid for Trade.

Conclusion

The recent contraction in international trade clearly shows that trade was one of the casualties of the global financial crisis. Middle-income countries, such as South Africa, Algeria and Morocco, were most affected, mainly due to the decline in exports in manufacturing goods and minerals. However, low-income countries, such as Burundi, which are exporters of agricultural products, were less affected by the crisis. Without a doubt, the global agenda for recovery from the global contraction will involve strong commitments on the international trade front, and concluding the Doha Trade Round should be at the top of the agenda.

Furthermore, initiatives such as Aid for Trade offer opportunities for the relevant countries to make investments in infrastructure, improve trade policy and regulation as well as productive capacity, with the view to expanding trade and consequently to boost economic growth. Therefore, Aid for Trade needs to involve long-term, predictable aid flows that can be fed into budgeting processes. More importantly, Aid for Trade must be a complement, rather than a substitute, for working towards a more progressive world trading system, which is one that does not prejudice the interests of developing countries. On the recipient side, the success of Aid for Trade will also entail strong political leadership at the country level, which is essential for the support of regional and national priorities.

Footnotes

1 United Nations (2009), World Economic Situation and Prospects 2009. New York: UNDESA