All high-income countries and many middle-income and low-income countries have social programmes intended to assist low-income individuals and families with their cash, housing, medical care, and other needs. Countries that have developed official measures of the fraction of individuals in poverty often calculate how many people are removed from poverty by their programmes. However, an issue that most countries have encountered is that a fraction - often a very sizable one – of those individuals and families who are eligible for the programmes do not, in fact, enrol and receive benefits. This makes the programmes less effective in achieving their primary goal and leaves needy individuals and families without assistance and with all the negative consequences for their well-being and that of their children that ensue from not having enough income (Deshpande and Mueller-Smith 2022).

Take-up rates around the world

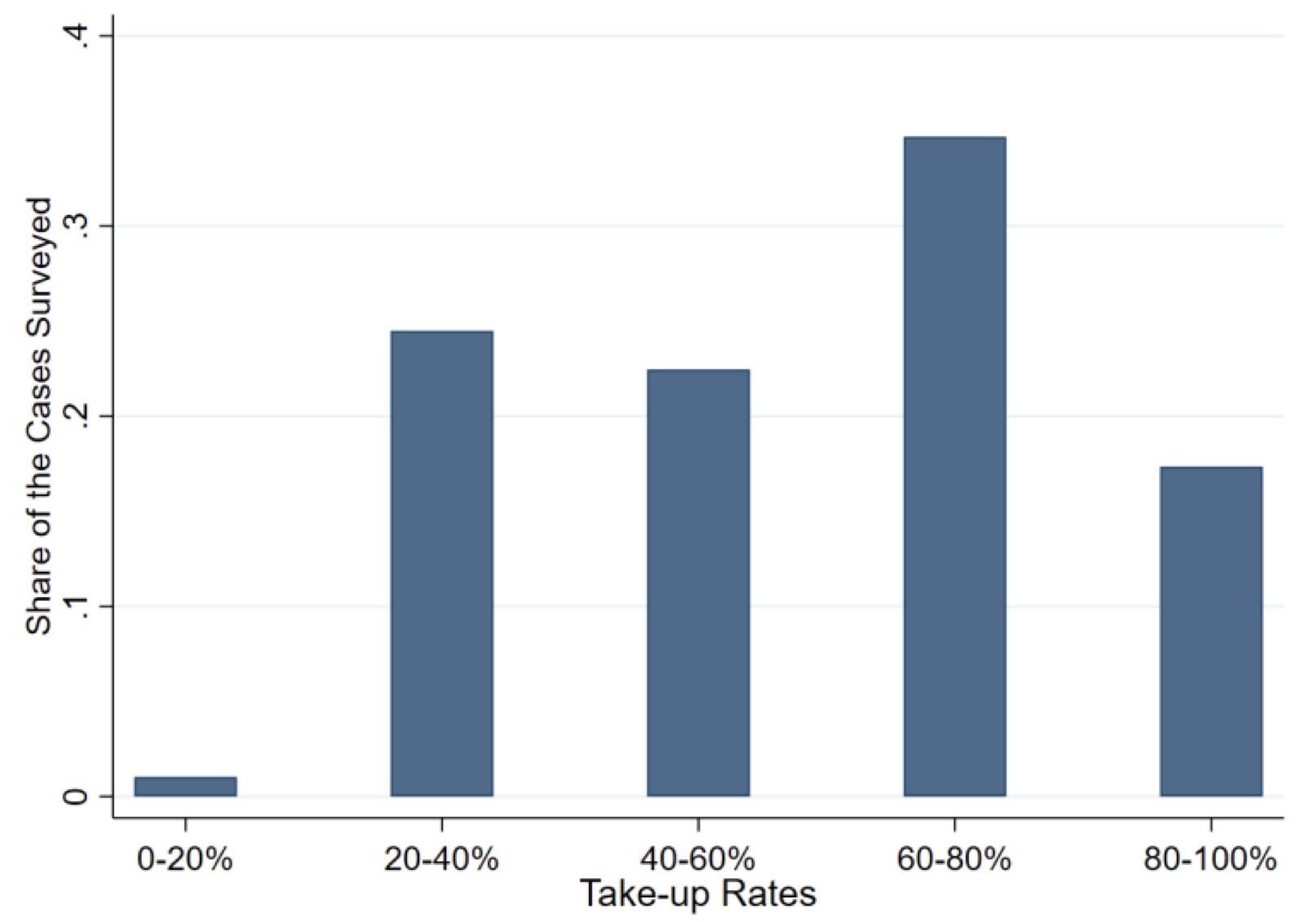

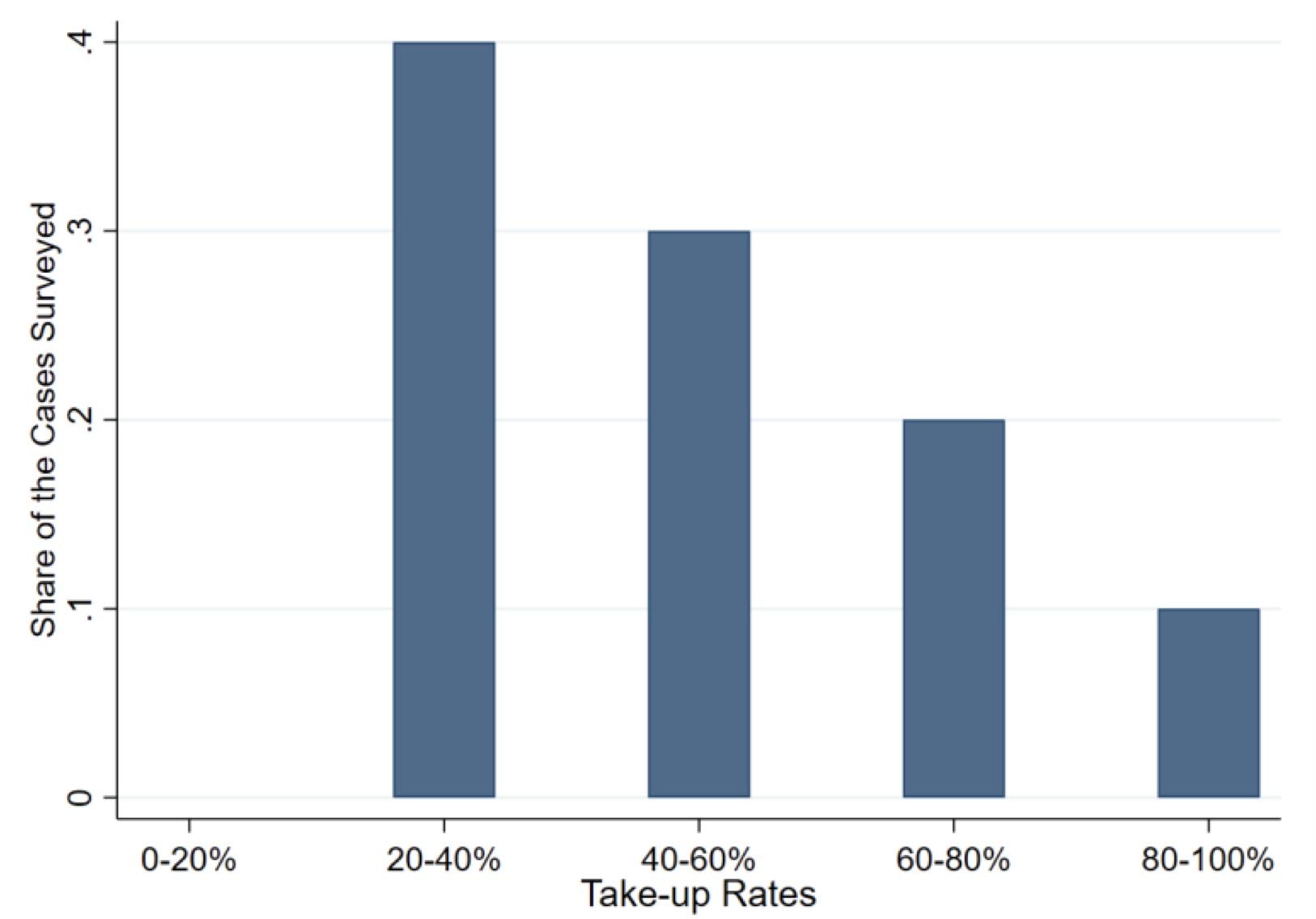

Take-up rates – defined as the percentage of individuals or families who are eligible for a programme who are also enrolled and receive benefits – have been calculated for a number of countries. Figure 1 shows rates for 20 high-income countries, indicating that less than one-fifth of programmes have take-up rates above 80%. Almost one-quarter have rates of 40% or below. Figure 2 shows rates for eight middle-income countries, where take-up rates are even lower, with about two-fifths at 40% or below and only 10% above 80%. No take-up rates are available for several countries with lower incomes, but take-up rates are known to be low for three of the largest and most well-known programmes: Dibao in China, Bolsa Familia in Brazil, and the Mahatma Gandhi National Rural Employment Guarantee Scheme programme in India.

Figure 1 Take-up rates of social benefits in high-income countries

Source: Ko and Moffitt (2022).

Figure 2 Take-up rates of social benefits in middle-income countries

Source: Ko and Moffitt (2022).

Research on causes and remedies

Research on the low take-up phenomenon has identified four main reasons for its existence (Van Oorschot 1991, Remler and Glied 2003, Hernanz et al. 2004, Currie 2006, Eurofound 2015, Van Mechelen and Janssens 2017, Goedeme and Janssens 2020, Lucas et al. 2021). One is a lack of information on eligibility, for many individuals seem not to know they are eligible (Da Ponte et al. 1999). Eligibility rules are complex, and understanding how they apply to any particular individual or family may be difficult. Individuals with low levels of education and literacy may find understanding whether they are eligible particularly challenging. The second reason is that many programmes have time-consuming and onerous requirements for applying for benefits, requiring multiple visits to a government office and with many requirements for documenting income, earnings and jobs, family circumstances, financial assets and bank accounts, the value of cars that might be owned, and so on (Herd and Moynihan 2018). Still, others have formidable work requirements (Gray et al. 2021). These barriers can also seem especially formidable to individuals who do not have the education or ability to deal with bureaucratic requirements.

The third reason for non-take-up is what is generally termed welfare ‘stigma’, which is the social aversion to being a welfare recipient (Moffitt 1983, Stuber and Schlesinger 2006). Sometimes this arises from lack of personal self-esteem and feelings of unworthiness when receiving government benefits, while in other cases it can be because recipiency may be visible or known to friends, family, or others in the individuals’ neighbourhood or social network. Some studies have suggested that stigma is higher when there are few others in the individual’s neighbourhood or network who are also recipients and, conversely, lower if large numbers of others are on receiving benefits. The fourth reason for non-take-up is that government agencies may themselves make errors in calculating eligibility, and benefits may be denied to some who are actually eligible (Kleven and Kopzcuk 2011, Moffitt and Zahn 2022).

In our study (Ko and Moffitt 2022), we review the research literature on the importance of these different factors. While it is difficult to apportion weights to the different reasons, all have appeared important for different programmes. A number of studies have conducted interviews with eligible families, which directly ask about the reason for non-participation (DaPonte et al. 1999, Gustafsson 2002, Eurofound 2015). Common answers are “lack of knowledge,” “do not need the benefit, can get along without it,” “would take too much time,” “offices are too far away,” “it would feel like begging,” and “it would not be good if participation were known around the neighbourhood”, which are consistent with the theories mentioned above. Many multivariate studies show positive effects of potential benefits on take-up (Bargain et al. 2007, Bruckermeier and Wiemers 2012, Daponte et al. 1999, Finn and Goodship 2014, Kayser and Frick 2000, Riphahn 2001, Whelan 2010), but several studies show that some of the neediest families do not enrol in programmes, suggesting that information barriers or administrative burden may fall hardest on such families (Kenney et al. 2012, Tempelman and Houkes-Hommes 2016, Falk 2017, Christensen et al. 2020)

Many studies show the importance of participation costs, documenting that take-up is related to geographic access and burdens of applying (Riphahn 2001, Rossin-Slater 2013), and others document how reducing barriers to participation increases take-up (Kopczuk and Pop-Eleches 2007, Fuchs et al. 2020). The US Food Stamp programme allowed different states to adopt simplified application procedures, which resulted in increased take-up (Dickert-Conlin et al. 2021, Ganong and Liebman 2018); other studies show that more onerous recertification barriers decrease rates of recertification (Ribar et al. 2008, Gray 2019, Homonoff and Somerville 2021).

Lack of information has also been shown to be an important barrier, and spending money on outreach programmes can increase take-up (Daponte et al. 1999, Aizer 2007, Dickert-Conlin et al. 2021). In a study that offered eligible non-recipients both information about their eligibility as well as assistance with applying for the US Food Stamp programme, Finkelstein and Notowidigdo (2019) found it increased take-up, although those who took advantage of the offer appeared to be less needy than those who did not.

The importance of behavioural factors in inhibiting take-up has been emphasised by Bertrand et al. (2006) and Van Mechelen and Janssens (2017). They review the literature and find that cognitive biases and behavioural factors play a large role in non-take-up. In this same behavioural category are a number of experiments in the US on increasing take-up of the Earned Income Tax Credit, a tax credit that requires filing tax returns and claiming the credit. These experiments test some type of ‘nudge’, which means a small and low-cost effort to increase information, encourage tax filing, offer application assistance, or, in some cases, reduce stigma. While some of these experiments have found modest effects, most show little or no impact (Bhargava and Manoli 2015, Guyton et al. 2017, Linos et al. 2020, Goldin et al. 2022).

Lessons for policymakers

The research suggests a number of lessons for policymakers. General postings of announcements or mass mailings of letters with nudges or other low-cost interventions may have little or no effect on take-up in this population. Publicity campaigns to advertise programme availability and encourage application, while more expensive, are more likely to have an impact. The evidence on the administrative burden of complex eligibility and benefit determination is very strong. This burden can be reduced by simplifying application and recertification forms and paying attention to the education level of the recipient in that process. More fundamental reductions in administrative burden are likely to require additional government expenditure on staff and IT systems (including neighbourhood ‘one-stop shopping centres’) to assist applicants and recipients in their compliance in a timely fashion. Reaching the most disadvantaged families is likely to be challenging and will require more effort. Using existing government tax and benefits programme administrative data to identify those who are likely eligible but not receiving benefits is often a means of identifying that group.

References

Aizer, A (2007), “Public health insurance, program take-up, and child health”, The Review of Economics and Statistics 89(3): 400-415.

Bargain, O, H Immervoll, and H Viitamäki (2007), “How tight are safety-nets in Nordic countries? Evidence from Finnish register data”, IZA Discussion Paper No. 3004

Bertrand, M, S Mullainathan, and E Shafir (2006), “Behavioral economics and marketing in aid of decision making among the poor”, Journal of Public Policy & Marketing 25(1): 8-23.

Bhargava, S and D Manoli (2015), “Psychological frictions and the incomplete take-up of social benefits: Evidence from an IRS field experiment”, American Economic Review 105(11): 3489-3529.

Bruckmeier, K and J Wiemers (2012), “A new targeting: a new take-up? Non-take-up of social assistance in Germany after social policy reforms”, Empirical Economics 43: 565-580.

Christensen, J, L Aarøe, M Baekgaard, P Herd, and D P Moynihan (2020), “Human capital and administrative burden: The role of cognitive resources in citizen-state interactions”, Public Administration Review 80(1): 127-136.

Currie, J (2006), “The take-up of social benefits”, in A J Auerbach et al. (Des), Public Policy and the Distribution of Income.

Daponte, B, O, S Sanders, and L Taylor (1999), “Why do low-income households not use food stamps? Evidence from an experiment”, Journal of Human Resources 1: 612-628.

Deshpande, M and M Mueller-Smith (2022), “Welfare can discourage crime more than it discourages work”, VoxEU.org, 5 July.

Dickert-Conlin, S, K Fitzpatrick, B Stacy, and L Tiehen (2021), “The downs and ups of the SNAP caseload: What matters?”, Applied Economics Perspectives and Policy 43(3): 1026-1050.

Eurofound (2015), “Access to social benefits: Reducing non-take-up”, Publications office of the European Union.

Falk, G (2017), “Temporary assistance for needy families (TANF): Size of the population eligible for and receiving cash assistance”, Congressional Research Service Report R44724.

Finkelstein, A and M J Notowidigdo (2019), “Take-up and targeting: Experimental evidence from SNAP”, The Quarterly Journal of Economics 134(3): 1505-1556.

Finn, D and J Goodship (2014), Take-up of benefits and poverty: an evidence and policy review, JRF/CESI Report

Fuchs, M, K Gasior, T Premrov, K Hollan, and A Scoppetta (2020), “Falling through the social safety net? Analysing non-take-up of minimum income benefit and monetary social assistance in Austria”, Social Policy & Administration 54: 827-843.

Ganong, P and J B Liebman (2018), “The decline, rebound, and further rise in SNAP enrollment: disentangling business cycle fluctuations and policy changes”, American Economic Journal: Economic Policy 10(4): 153-176.

Goedemé, T and J Janssens (2020), “The concept and measurement of non-take-up: An overview, with a focus on the non-take-up of social benefits”, Deliverable 9.2, Leuven, InGRID-2 project 730998 – H2020.

Goldin, J, T Homonoff, R Javaid, and B Schafer (2022), “Tax filing and take-up: Experimental evidence on tax preparation outreach and benefit claiming”, Journal of Public Economics 206: 104550.

Gray, C (2019), “Leaving benefits on the table: Evidence from SNAP”, Journal of Public Economics 179: 104054.

Gray, C, A Leive, E Prager, K Pukelis, and M Zaki (2021), “Evidence on the effects of work requirements in safety net programmes”, VoxEU.org, 4 October.

Gustafsson, B (2002), “Assessing non-use of social assistance”, European Journal of Social Work 5(2): 149-158.

Guyton, J, P Langetieg, D Manoli, M Payne, B Schafer, and M Sebastiani (2017), “Reminders and recidivism: Using administrative data to characterise nonfilers and conduct EITC outreach”, American Economic Review 107(5): 471-475.

Herd, P and D Moynihan (2018), “Administrative burden: Policymaking by other means”, Russell Sage Foundation.

Hernanz, V, F Malherbet, and M Pellizzari (2004), “Take-up of welfare benefits in OECD countries: A review of the evidence”, OECD Social, Employment and Migration Working Papers.

Homonoff, T and J Somerville (2021), “Program recertification costs: Evidence from SNAP”, American Economic Journal: Economic Policy 13(4): 271-298.

Kayser, H and J R Frick (2000), “Take it or leave it: (Non-) take-up behavior of social assistance in Germany”, DIW Discussion Papers.

Kenney, G, M, V Lynch, J Haley, and M Huntress (2012), “Variation in Medicaid eligibility and participation among adults: Implications for the Affordable Care Act”, INQUIRY: The Journal of Health Care Organization, Provision, and Financing 49(3): 231-253.

Kleven, H, J and W Kopczuk (2011), “Transfer program complexity and the take-up of social benefits”, American Economic Journal: Economic Policy 3(1): 54-90.

Ko, W and R A Moffitt (2022), “Take-up of Social Benefits”, Handbook of Labor, Human Resources, and Population Economics, forthcoming

Kopczuk, W and C Pop-Eleches (2007), “Electronic filing, tax preparers, and participation in the Earned Income Tax Credit”, Journal of Public Economics 91(7-8): 1351-1367.

Linos, E, A Prohofsky, A Ramesh, J Rothstein, and M Unrath (2020), “Can nudges increase take-up of the EITC?: Evidence from multiple field experiments”, NBER Working Paper No. w28086.

Lucas, B, J M Bonvin, and O Hümbelin (2021), “The non-take-up of health and social benefits: What implications for social citizenship?”, Schweizerische Zeitschrift für Soziologie 47(2): 161-180.

Moffitt, R, A (1983), “An economic model of welfare stigma”, The American Economic Review 73(5): 1023-1035.

Moffitt, R, A and M V Zahn (2022), “The marginal labor supply disincentives of welfare: Evidence from administrative barriers to participation”, NBER Working Paper No. w26028.

Remler, D, K and S A Glied (2003), “What other programs can teach us: Increasing participation in health insurance programs”, American Journal of Public Health 93(1): 67-74.

Ribar, D, C, M Edelhoch, and Q Liu (2008), “Watching the clocks The role of Food Stamp recertification and TANF time limits in caseload dynamics”, Journal of Human Resources 43(1): 208-238.

Riphahn, R, T (2001), “Rational poverty or poor rationality? The take-up of social assistance benefits”, Review of Income and Wealth 47(3): 379-398.

Rossin-Slater, M (2013), “WIC in your neighborhood: New evidence on the impacts of geographic access to clinics”, Journal of Public Economics 102: 51-69.

Stuber, J and M Schlesinger (2006), “Sources of stigma for means-tested government programs”, Social Science & Medicine 63(4): 933-945.

Tempelman, C and A Houkes-Hommes (2016), “What stops Dutch households from taking up much needed benefits?”, Review of Income and Wealth 62(4): 685-705.

Van Mechelen, N and J Janssens (2017), “Who is to blame? An overview of the factors contributing to the non-take-up of social rights”, Working Paper No.17.08 Herman Deleeck Centre for Social Policy.

Van Oorschot, W (1991), “Non-take-up of social security benefits in Europe”, Journal of European Social Policy 1(1): 15-30.

Whelan, S (2010), “The take-up of means-tested income support”, Empirical Economics 39: 847-875.