Students learn from their teachers. How much students learn depends on which teacher they are assigned. The differences can be large and have consequences years or decades later in adulthood (Chetty et al. 2014). These conclusions may not be new, but empirical research has increasingly made clear the magnitude of the differences between teachers (see Jackson et al. 2014 for a broad survey, and Bacher-Hicks and Koedel 2023 for a more specific discussion). Motivated by those differences, educators, researchers, and policymakers continually investigate and debate how best to improve teaching (see the recent review in Taylor 2023). Some proposals focus on strengthening the skills of current teachers; such in-service training has long been the focus of schools’ efforts and spending. Other proposals focus on improving teaching by changing teacher compensation or through pay for performance (Burgess et al. 2022b). Still other proposals focus on changing the composition of the teacher workforce – changing who teaches – through hiring (Jacob et al. 2018), dismissals (Gordon et al. 2004), and incentives for joining the teacher workforce (De Ree et al. 2018).

In the ever-growing research base on teaching, little attention has been given to how school and class time is used. High school teachers have many hours a year with each group of students, and a set of material to cover. How should teachers use that class time? Is it best spent in direct instruction, lecturing from the front of the class? Or perhaps pupils learn more by discussing in small groups. These are practical but important questions. Effective teaching is a central factor in building human capital, crucial for economic growth (Patrinos et al. 2021) and reducing inequality (Blanden et al. 2023). Two decades of research on teachers (Hansuhek 2011, Slater et al. 2011) has shown that teacher effectiveness is very significant economically, and reasonably consistently so across countries and phases of education. But such findings are not enough on their own if ‘teacher effectiveness’ remains a black box – if we don’t know what effective teaching looks like in practice. How do classroom practices differ between teachers? And, most importantly, are some classroom activities more effective than others for pupil progress?

The obvious answer is: let’s look what the evidence says. Unfortunately, while there is no end of opinion on this, strong evidence is very hard to find. In recent research (Burgess et al. 2022a) we are unlock the black box by beginning to characterise effective teaching. In a large-scale study, the first of its type in England, we can identify which teaching practices contribute best to raising pupils’ GCSE grades. Our work also leads to a cheap and easy tool that teachers and teacher-leaders can use to identify and improve skills. Our findings therefore help students (better GCSEs means better life chances), teachers (offering a way to evaluate and improve their own teaching practices), and school leaders (potentially raising the success of teacher recruitment).

We combine two types of data: detailed classroom observation of teachers by teachers, and the test scores of the students they teach. While this has been done a few times in the US, they are unique data for England, involving observations over two years and at scale. In total we use data from over 2,500 classroom observations and looked at close to 10,000 GCSE scores in 32 schools in high-poverty neighbourhoods in England.

We find economically meaningful and statistically significant relationships between teachers’ observed classroom practices and student test scores. While these effects are small as a share of the total variation in test scores, they are large as a share of teachers’ contributions to test scores – around one-third of the teacher’s entire contribution to student learning. This is what we mean by characterising effective teaching.

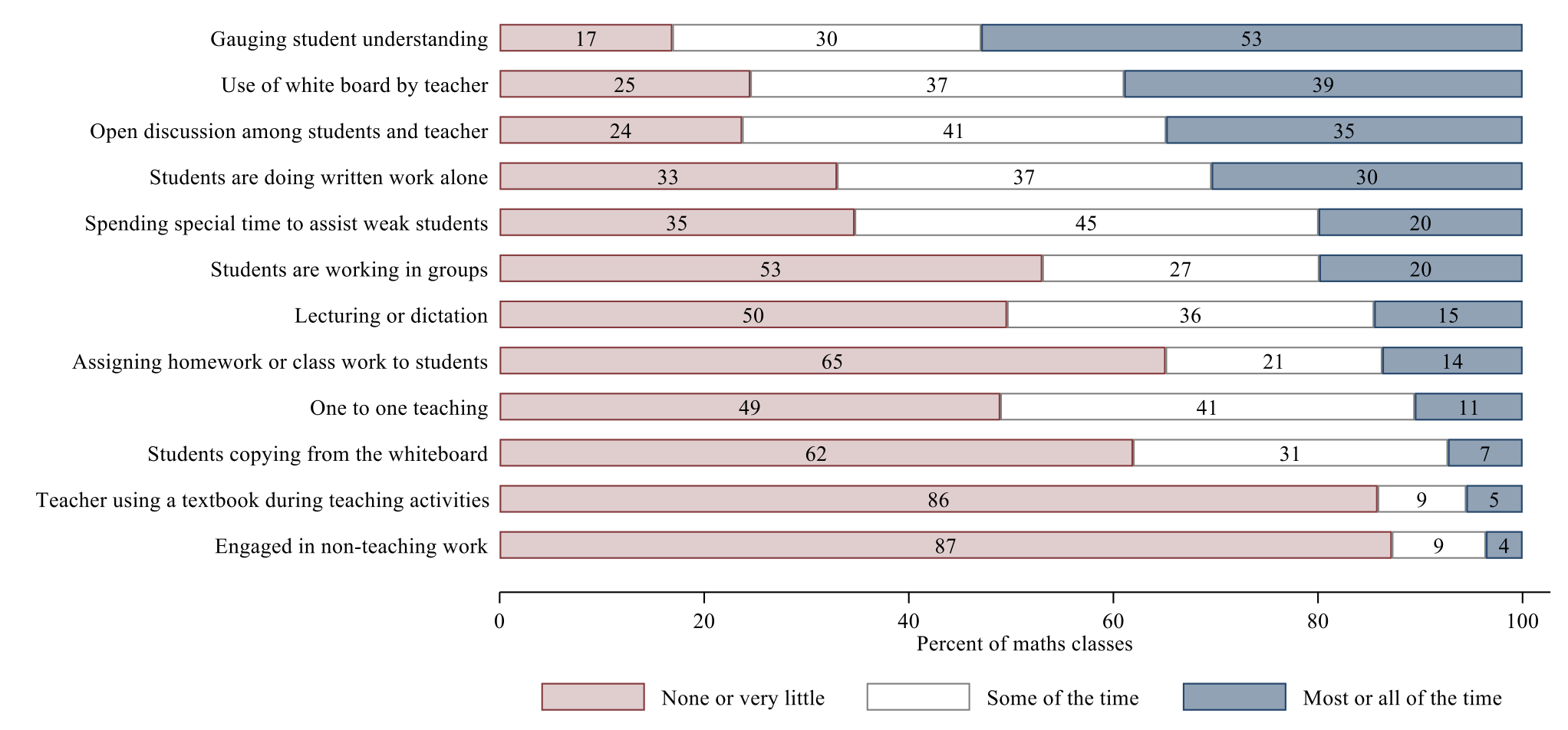

The first point to establish is that teachers make very different choices about how to use class time. For example, for the activity “Open discussion among students and teacher”, a quarter of lessons contained none or very little, while a third had that activity for most of the time. By contrast, for “using a textbook”, in 86% of the classroom observations this barely happened at all. Even when we take account of the subject being taught, student ability, and other characteristics, it is still the case that teachers make very different decisions on how to spend class time. The distribution of time for all the activities for mathematics shows substantial variation between classes.

Figure 1 Teacher time use in class for mathematics

Our key finding is that these differences in instructional choices matter for GCSE scores, even once we take account of the teacher’s instructional skills. Interestingly, we find different classroom activities are important for maths and English. In maths classes, for example, students score higher on the GCSE exams when their teachers give more time for individual practice. For English exams, the key activity that raises GCSE scores is peer interaction (i.e. working with classmates).

The size of these effects is significant. Recent work has been able to assign monetary values to increases in GCSE exam scores, as they influence both job market chances and university admissions, and this allows us to quantify the impact of a change in classroom practices for a student’s life chances. An English teacher increasing time spent on peer interaction by one standard deviation improves test scores for her class of 30 and generates an additional £150,000 of lifetime income for her students, every year. The predicted earnings gains are perhaps twice as high for increases in maths GCSE scores; furthermore, as the impact of teacher effectiveness is greater for lower ability students, the subsequent earnings gain would also be greater for them.

Interventions around class time use are relatively cheap and feasible: the process for a school to generate the required data on classroom activities is simple, administratively modest, and politically feasible. The observations are carried out by peer teachers and our observers received little training, much less training than is often described as necessary for ‘reliable’ observations. These results can help inform teachers’ own decisions and improvement efforts. For example, our results emphasise the importance of individual student practice for maths, and so suggest the typical maths teacher should allow a little more time for student practice and for building related teaching skills.

References

Bacher-Hicks, A and C Koedel (2023), ‘Estimation and Interpretation of Teacher Value Added in Research Applications”, in E Hanushek, S Machin, and L Woessmann (eds), Handbook of Economics of Education, Volume 6, Elsevier.

Blanden, J, M Doepke and J Stuhler (2023), ‘Educational inequality” in in E Hanushek, S Machin, and L Woessmann (eds), Handbook of Economics of Education, Volume 6, Elsevier.

Burgess, S, S Rawal and E Taylor (2022a), “Teachers’ Use of Class Time and Student Achievement”, NBER Working Paper No. 30686.

Burgess, S, E Greaves and R Murphy (2022b), “Deregulating Teacher Labor Markets”, Economics of Education Review 88.

Chetty, R, J Friedman and J Rockoff (2014), “Measuring the Impacts of Teachers II: Teacher Value-Added and Student Outcomes in Adulthood”, American Economic Review 104(9): 2633-79.

De Ree, J, K Muralidharan, M Pradhan and H Rogers (2018), “Double for nothing? Experimental evidence on an unconditional teacher salary increase in Indonesia”, The Quarterly Journal of Economics 133(2): 993-1039.

Gordon, R, T J Kane, and D O Staiger (2006), "Identifying Effective Teachers Using Performance on the Job. The Hamilton Project Policy Brief No. 2006-01", Brookings Institution.

Hanushek, E A (2011), "The economic value of higher teacher quality," Economics of Education Review 30(3): 466-479.

Jackson, C K, J E Rockoff and D O Staiger (2014), “Teacher Effects and Teacher-Related Policies”, Annual Review of Economics 6: 801-825.

Jacob, B A, J E Rockoff, E S Taylor, B Lindy and R Rosen (2018), “Teacher applicant hiring and teacher performance: Evidence from DC Public Schools”, Journal of Public Economics 166: 81-97.

Patrinos, H A, S Djankov, P Goldberg and N Angrist (2021), “Measuring human capital: Learning matters more than schooling”, VoxEU.org, 9 April.

Slater, H, N M Davies and S Burgess (2011), “Do Teachers Matter? Measuring the Variation in Teacher Effectiveness in England”, Oxford Bulletin of Economics and Statistics 74: 629-645.

Taylor, E (2023), “Teacher evaluation and training”, in E Hanushek, S Machin, and L Woessmann (eds), The Handbook of the Economics of Education, Volume 7, Elsevier (in press).