World food commodities prices increased 130% from January 2002 to July 2008. Individual agricultural commodities show even more pronounced increases: corn (up 190%), wheat (162%), rice, (318%) and soybeans (246%) rose dramatically. Food prices began to fall in July, bringing some relief, but prices are likely to stay high for the foreseeable future. What does this mean for the poor?

Net sellers vs. net buyers of food

Since the poor include both net consumers and net sellers of food commodities, an increase in food prices will inevitably hurt some (poor urban dwellers and landless rural residents) and benefit others (small poor farmers).

Food price increases’ overall impact on poverty depends on:

- The relative importance of different food commodities in the production set and consumption basket of different households and the difference between the two;

- The magnitude of the relative price change;

- The degree to which households are compensated for the price shocks by changes in their income (i.e., by the indirect effect on wages and employment originated by the price change).

Evidence

Studies suggest that the poor spend between 60% and 80% of their income on food on average. Among the poorest of the poor, many are net consumers of food. For them, the increase in domestic food price has been significant, and the positive effects on wages lag behind.

Empirical evidence shows that the decline in living standards of net consumers caused by the recent increase in food prices outweighs the benefits accruing to net sellers in the majority of countries that have been analysed so far. Ivanic and Martin (2008) show that about 105 million people in the least developed countries have been added to the world’s poor since 2005 because of rising food prices. This is equivalent to about 10% of those living on less than a dollar a day and, according to the authors, “close to seven lost years of progress in poverty reduction” (p.17). The Asian Development Bank (2008) suggests that a 20% increase in food prices would raise the number of poor individuals by 5.7 and 14.7 million in the Philippines and Pakistan, respectively.1 Even middle-income Latin America would not remain impervious – Robles et al. (2008) estimate that the increase in world food prices between January 2006 and March 2008 added 21 million newly impoverished individuals. CEPAL (2008)—the UN Economic Commission for Latin America and the Caribbean-- estimates that the ranks of the extremely poor and the moderately poor increased by 10 million each.2

Where are the safety nets?

Undoubtedly, throughout the developing world, poor net buyers have been adversely affected by higher food prices and net buyers living just above the poverty line are likely to have become poor. In a recent paper (Lustig 2008), I ask: Are developing countries ready to compensate these groups for their loss in purchasing power? In particular, do safety net programmes exist and can they be easily expanded to incorporate the “new” poor? Do governments have the fiscal space to accommodate the additional resources needed to fund the safety net?

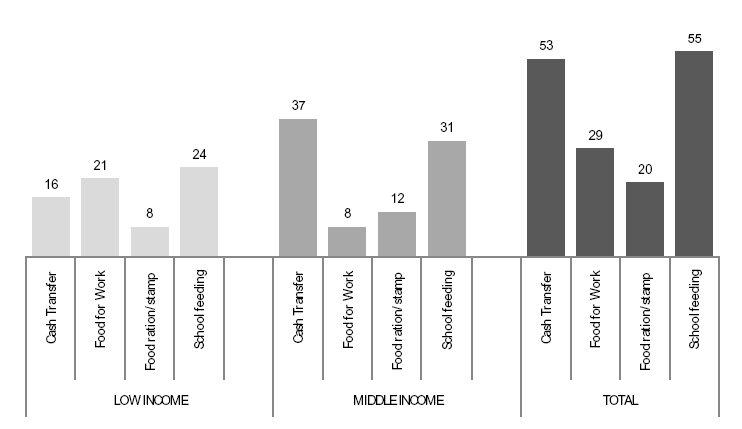

Figure 1 presents the safety net programmes available in low and middle-income countries by category: cash transfers, food for work, food ration/stamp, and school feeding programmes. Unfortunately 19 out of 49 low-income and 49 out of 95 middle-income countries still do not have safety net programmes.

Figure 1. Safety net programmes in low- and middle-income countries

Source: Author’s construction based on information from the World Bank and Asian Development Bank. The World Bank classifies 49 countries as low-income and 95 as middle-income; in the graph are those countries that have one or more of the selected safety net programmes: 30 low income and 46 middle income countries.

Given that the shock is a price increase rather than reduced supply, the most adequate safety net is to compensate the affected population for their loss in purchasing power in cash. As Figure 1 shows, fewer than half of low- and middle-income countries have cash transfers programmes.

Safety net programmes are not only rare but also have limited coverage. In the case of Latin America and the Caribbean, for example, the coverage of cash transfer programmes exceeds 25% of the population living in poverty in only 8 out of 26 countries: Brazil, Colombia, Chile, Ecuador, Honduras, Jamaica, Mexico and Panama. The good news is that the largest programmes are in the most populous countries (Brazil and Mexico). The bad news is that the region’s poorest countries have very small or non-existent programmes.

One key limitation of cash transfer programmes is that they do not have a mechanism to incorporate the “new” poor or increase the size of the benefit in the face of adverse shocks as part of their design. They are not a “safety net” in the full sense of the concept. Some governments have increased the amount of the transfer to compensate for the loss in its purchasing power but this has been an ad hoc response that was implemented a year or more after food prices began to rise. Furthermore, the programmes have not incorporated as beneficiaries those who became poor as a result of the food price increase. Food-for-work programmes are better suited in this respect because of their ability to self-target. However, since the shock adversely affects purchasing power and not employment, such programmes are not the best instruments to protect the poor from a rise in food prices.

Better coping mechanisms

Are there other measures that can be implemented to help poor consumers cope with rising food prices? De Janvry and Sadoulet (2008) suggest that measures geared to increase access to land and improve the productivity of subsistence and below-subsistence farmers would be a more appropriate intervention in poor countries.

In low-income countries, between 80% and 90% of the poor live in rural areas, and between two-thirds and three-fourths of them have access to a plot of land. However, even if they produce some of the food they consume, most of them are net buyers of food and are hurt by higher food prices. Giving this group access to more land or more productive methods would reduce their dependence on purchasing food in the market and begin to address the supply-side constraints on food production. De Janvry and Sadoulet recommend policy measures to improve access to seeds, fertilisers, small animals, land, credit to purchase inputs, and technical assistance.

Low-income countries for whom higher commodity prices represent a negative terms of trade shock (which includes 47 of the 61 that are eligible for the IMF Poverty Reduction and Growth Facility) may not have the fiscal space to finance an expansion let alone launch new safety net programmes. These countries are candidates for receiving multilateral support in the form of grants or concessional loans to fund safety net programmes to cope with rising food prices. The World Bank, for example, has already approved more than $120 million dollars in grants to bolster the safety net system in 14 low-income countries and an additional $400 million dollars is in the pipeline.

Conclusions

In sum, the existing safety net system in developing countries leaves much to be desired. In too many countries, it is either inexistent or small. Many countries do not have the fiscal space to fund new safety net programmes or expand existing ones. Even in the countries in which, for example, cash transfers programmes are large and effective in addressing chronic poverty, they are not designed to respond to shocks. This means that very large numbers of the poor who have been hurt or those who have become poor as a result of higher food prices are not being protected. Policymakers and multilateral institutions should give priority to implementing safety net programmes where they do not exist, making sure that both the new and existing safety net programmes are able to increase the size of benefits and to incorporate the “new” poor fast enough (i.e., include mechanisms to screen in and screen out beneficiaries as needed), and allocating the additional fiscal resources needed to fund a new or expanded safety net.

References

Asian Development Bank (2008) “Food Prices and Inflation in Developing Asia: Is Poverty Reduction Coming to an End?” Special Report, Asian Development Bank.

Comision Economica para America Latina y el Caribe, CEPAL (2008) “Latin America and the Caribbean in the New International Economic Environment.” Report of the Comision Economica para America Latina y el Caribe (Economic Commission for Latin America and the Caribbean.)

De Janvry, Alain and Elisabeth Sadoulet (2008) “How to manage a quick response to the food crisis in poor countries with weak policy instruments?” Unpublished document.

International Monetary Fund (2008) “Food and Fuel Prices—Recent Developments, Macroeconomic Impact, and Policy Responses.” Prepared by the Fiscal Affairs, Policy Development and Review, and Research Departments. International Monetary Fund Report.

Ivanic, Maros and Martin, Will (2008) “Implications of higher global food prices for poverty in low-income countries.” Policy Research Working Paper Series 4594, The World Bank.

Lustig, Nora (2008) “Thought for Food: the Challenges of Coping with Soaring Food Prices,” Working Paper, Center for Global Development, Washington DC, forthcoming.

Robles, Marcos; Jose Cuesta; Suzanne Duryea; Ted Enamorado; Alberto Gonzales, and Victoria Rodríguez (2008) “Rising Food Prices and Poverty in Latin America: Effects of the 2006-2008 Price Surge.” Inter-American Development Bank.

Von Braun, Joachim et al. (2008b) “High Food Prices: The What, Who, and How of Proposed Policy Actions.” Policy Brief, International Food Policy Research Institute.

Von Braun, Joachim et al. (2008c) “Rising Food Prices: What Should Be Done?” Policy Brief, International Food Policy Research Institute.

Wodon, Quentin et al. (2008) “The Food Price Crisis in Africa: Impact On Poverty And Policy Responses.” World Bank (mimeo).

World Bank (2008d) “Double Jeopardy: Responding to High Food and Fuel Prices.” G8 Hokkaido-Toyako Summit. Washington, DC: World Bank.

Editor's note: Listen to an interview with Nora Lustig here.

Footnotes

1 For a more extreme scenario of 30% increase in food prices, the number of poor people increases by 8.85 and 21.96 million in the Philippines and Pakistan, respectively.

2 None of these estimates account for the potential of higher food prices to increase economic growth and decrease poverty in countries that are net exporters of food commodities. Since net exporters are fewer and richer than the net importers, the overall impact on poverty in low-income countries may not change much even if the commodity boom-driven growth dividend for net exporters is taken into account.