Business dynamism – and in particular, the process of firm entry and exit – is key for creative destruction and to foster resource reallocation, both crucial elements of long-run economic growth.

Earlier Vox columns have highlighted that entry declined substantially in the first months of the COVID-19 pandemic, with significant and persistent estimated effects on employment (Calvino et al. 2020b, Sedláček and Sterk 2020). At the same time, the drop in global demand induced by the COVID-19 crisis could have translated into a wave of corporate insolvencies, especially for small and young firms (Demmou et al. 2021).

More recent columns have documented a rise in business dynamism in the US (Djankov and Zhang 2021) and a decline in the number of bankruptcies across countries (Djankov and Zhang 2021, Cross et al. 2021). Differences across countries in the extent to which creative destruction may have been affected by the crisis and government support have also been highlighted (Bénassy-Quéré et al. 2021, Bighelli et al. 2021, Cross, Epaulard and Martin 2021, Fareed and Overvest 2021, Freeman et al. 2021).

In an OECD COVID-19 Hub policy brief (OECD 2021a), we present novel cross-country evidence on both business registrations and bankruptcies and analyse sectoral dynamics during the COVID-19 pandemic. Based on publicly available monthly or quarterly data collected from official sources, we then develop an interactive visualisation tool that allows researchers and policymakers to navigate most recent data and disaggregate them at the sectoral or regional level. The tool is now publicly available on the OECD DynEmp project webpage.1

In this column, we discuss some key findings from analysing these data. Focusing on firm entry and exit is particularly relevant at this time, with a growing policy debate about the future of emergency measures and their possible phasing out or retargeting, as well as increasing discussions about how policy can strengthen business dynamism to support recovery and address long-term challenges (Calvino et al. 2020).

Start-ups at the time of COVID-19

New and young firms are key for job creation, innovation, and economic growth. During recessions, however, a fall in firm entry may amplify the drop in output and reduce the speed of recovery (Clementi and Palazzo 2016), potentially leaving long-lasting scars to the economy (Sedláček 2020, Gourio et al. 2016).

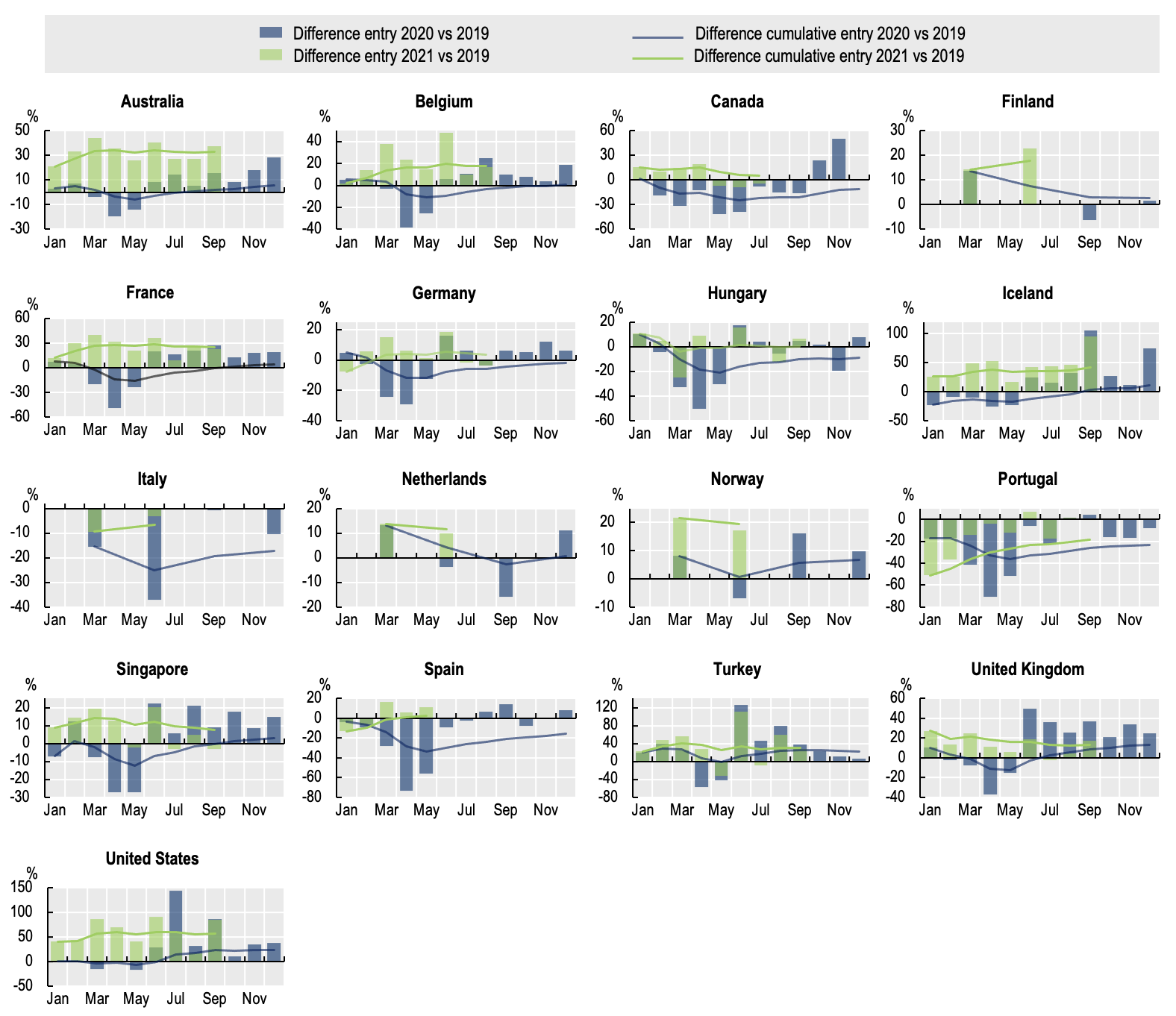

Data from 17 countries show that entry declined substantially in the first months of the COVID-19 pandemic. At its trough (which was April 2020 for most countries), the number of new entrants per month had fallen to 15%–80% lower than in the same month in 2019 (Figure 1).

Figure 1 Aggregate business registration: Differences 2020 vs 2019 and 2021 vs 2019

Notes: The figure plots the difference in business openings each month (or quarter for Finland, Italy, the Netherlands, and Norway) of 2020 or 2021, in percentage, comparing the level of business openings to the same month (quarter) of 2019 (blue and green bars). The blue and green lines instead represent the difference in percentage of cumulative openings from January to each month considered versus cumulative openings over the same period in 2019. Data usually refer to business registrations, focusing when possible on all businesses (including sole proprietorship). Data may be preliminary, experimental and subject to revision, and differ from official data.

Source: OECD calculations based on official sources: Australia, Australia Securities & Investments Commission; Belgium, Statistics Belgium; Canada, Statistics Canada; Finland, Statistics Finland; France, INSEE; Germany, Destatis; Hungary, Hungarian Central Statistical Office; Iceland, Internal Revenue Directorate; Italy, Unioncamere; Netherlands, CBS - Statistics Netherlands; Norway, Statistics Norway; Portugal, Statistics Portugal; Singapore, Singapore Department of Statistics; Spain, Instituto Nacional de Estadistica; Turkey: the Union of Chambers and Commodity Exchanges of Turkey; United Kingdom, Office for National Statistics; US, US Census Bureau.

Starting in June 2020, entry generally improved. Yet, the strength of the recovery displayed a substantial degree of heterogeneity across countries. Some countries (such as Australia, Belgium, France, Norway, Singapore, the UK, and the US) experienced a ‘V-type’ rapid recovery: the rebound was sufficiently strong to offset the losses in total entry registered since the beginning of 2020. In some countries, total entry rose significantly in 2020 compared to the previous year (e.g. in the UK and the US). In most of these countries, entry continued to rise significantly in 2021 compared to 2019. These patterns tend to be confirmed when focusing on registered companies, suggesting that these dynamics may not be driven only by self-employment related to necessity entrepreneurship.

Other countries (including Hungary, Italy, Portugal and Spain) seemed to struggle with a slower ‘U-type’ recovery: business registrations rose less significantly after June 2020 (and continued to decline in some cases). As a result, by the end of 2020, the total number of entrants remained significantly below the 2019 level, and entry remained also low in 2021, particularly in Italy and Spain.

In the first group of countries, the inflow of start-ups may foster recovery and help alleviate the employment effects of the crisis. In the second group of countries, the effects of a missing generation of new firms may persistently weigh on aggregate employment.

Figure 1 also shows that the second wave of the pandemic, experienced at the end of 2020 in many countries, has not translated into similar widespread drops in entry as in the early stage of the pandemic. It has, however, slowed down to some extent the rebound started in June.

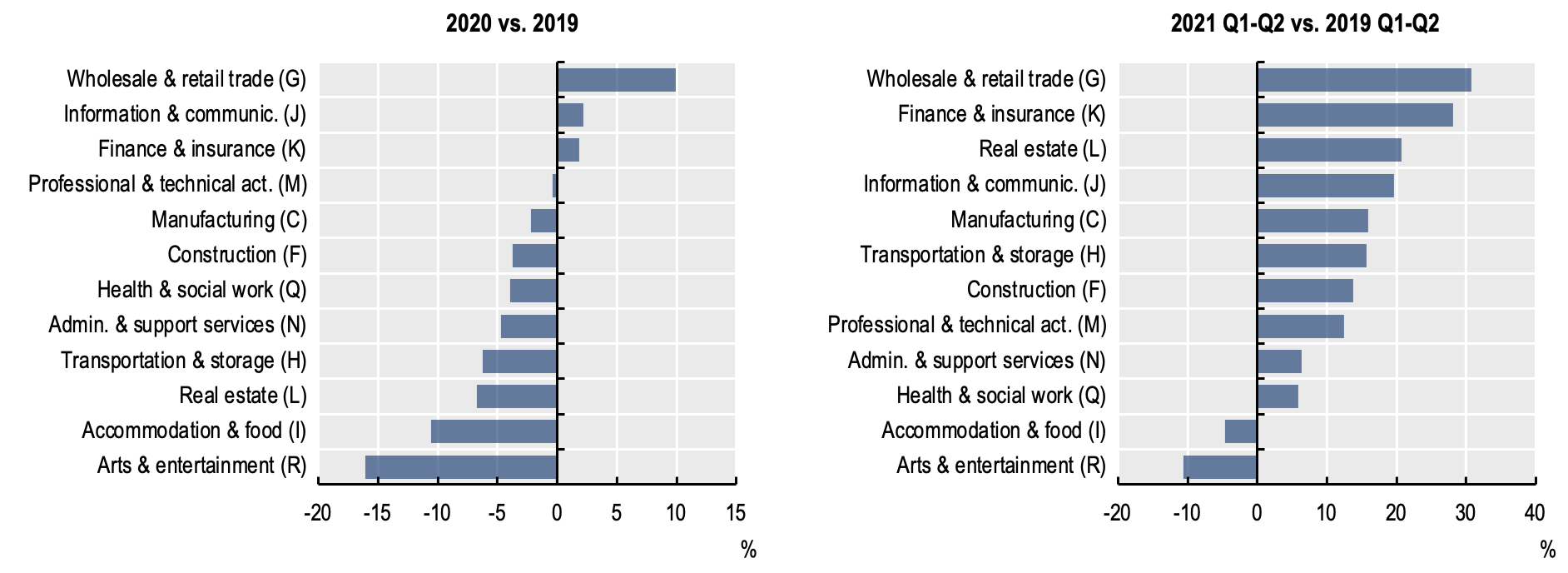

Our online visualisation tool further provides insights into sector-specific dynamics and the contribution of sectors to aggregate changes during the crisis and the recovery. Exploiting data for eight countries, we find that the trade sector (wholesale and retail) has been more resilient in 2020 and has experienced the largest rise in entry in 2021 (Figure 2).2 The rise in entry in the first semester of 2021 has been widespread across sectors. Yet, in service sectors such as arts and entertainment and accommodation and food, entry has continued to decline in 2021.3

Figure 2 Change in entry in 2020 and 2021 relative to 2019, by sectors

Notes: The figure plots the percentage difference in business openings in 2020 relative to 2019 (left panel), and 2021 Q1 and Q2 relative to 2019 Q1 and Q2 (right panel), by sectors. Sectors are converted from the original classification to ISIC rev. 4 sections when needed. Each bar reports a cross-country average based on Belgium, Canada, Finland, Italy, the Netherlands, Norway, Portugal, and the US. Data usually refer to business registrations, focusing when possible on all businesses (including sole proprietorship). In some countries (e.g. Italy and Norway), information on the sector is missing for a significant share of business openings. Data may be preliminary, experimental and subject to revision, and differ from official data.

Source: OECD calculations based on official sources: Belgium, Statistics Belgium; Canada, Statistics Canada; Finland, Statistics Finland; Italy, Unioncamere; Netherlands, CBS - Statistics Netherlands; Norway, Statistics Norway; Portugal, Statistics Portugal; US, US Census Bureau.

The online visualisation tool allows us to explore these patterns in greater detail, focusing on specific countries, customised time periods and additional breakdowns of the data. It reveals significant heterogeneity across countries in aggregate and sectoral dynamics.

Bankruptcies over the pandemic

During the pandemic, governments adopted a range of emergency measures to support firms’ liquidity and curb the potential spike in bankruptcies (Kasinger et al. 2021).

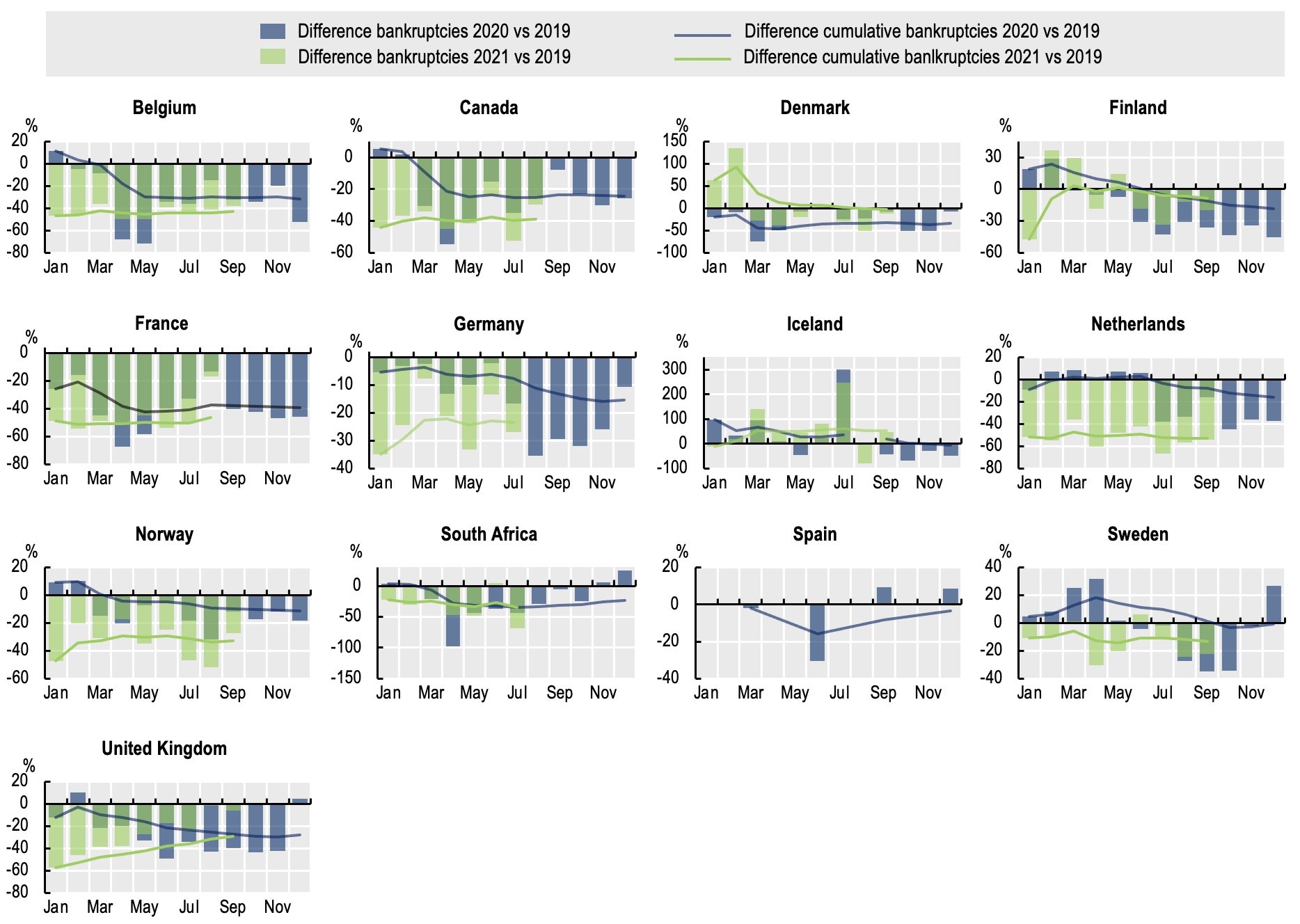

Figure 3 Aggregate number of bankruptcies: differences 2020 vs. 2019 and 2021 vs. 2019

Notes: The figure plots the difference in bankruptcies each month (or quarter Spain) of 2020 or 2021, in percentage, comparing the level of business openings to the same month (quarter) of 2019 (blue and green bar). The blue and green lines instead represent the difference in percentage of the cumulative number of bankruptcies from January to each month considered versus cumulative bankruptcies over the same period in 2019. Data may be preliminary and subject to revisions and may differ from official data.

Source: OECD calculations based on official sources: Belgium, Statistics Belgium; Canada, Canada Revenue Agency; Denmark, Statistics Denmark; Finland, Statistics Finland; France, Banque de France; Germany, Federal Statistical Office of Germany; Iceland, Statistics Iceland; Netherlands, CBS - Statistics Netherlands; Norway, Statistics Norway; Spain, Instituto Nacional de Estadistica; South Africa, Statistics South Africa; Sweden, Statistics Sweden; United Kingdom, UK Government - The Insolvency Service.

Our online data visualisation tool, covering information on bankruptcies for 13 OECD countries and partner economies and drawing from various official sources, shows that these measures have been effective in reducing bankruptcies. Cumulative bankruptcies dropped by more than 25% on average in 2020 relative to 2019, and were on average 40% lower in the first semester of 2021 relative to the same period in 2019. These dynamics are echoed by declines in measures of exit (e.g. based on termination or deregistration), also presented on our data visualisation tool.4

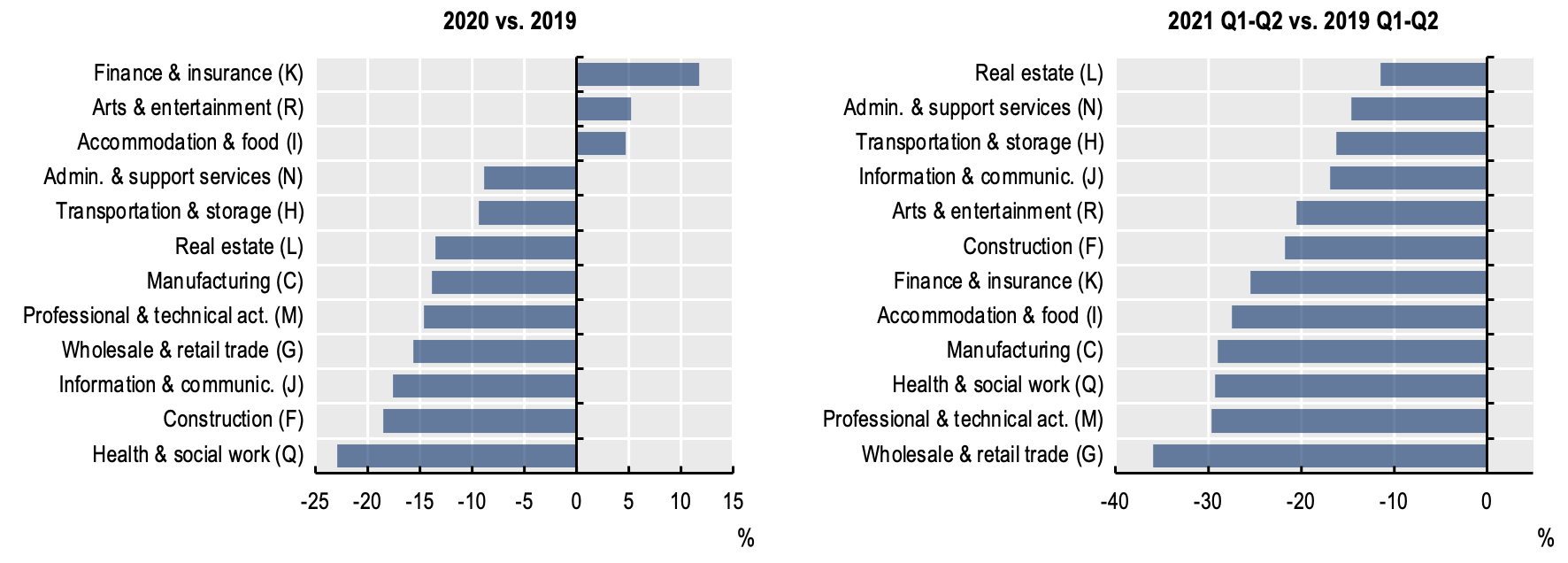

The online visualisation tool provides additional insights based on sectoral data, illustrated in Figure 4 (reporting averages across seven countries). While most sectors have experienced significant declines in the number of bankruptcies in 2020, accommodation and food services, arts and entertainment, and finance and insurance have experienced on average an increase in bankruptcies (with significant heterogeneity across countries).

Focusing on the first half of 2021, the trade sector shows the strongest decline in bankruptcies, echoing the resilience suggested by dynamics observed for entry. It is also noteworthy that some heavily affected sectors (such as accommodation and food, or arts and entertainment) also display significant declines in bankruptcies relative to 2019 over the first half of 2021, reflecting the role of governments’ support.5

Figure 4 Change in bankruptcies in 2020 and 2021 relative to 2019, by sector

Notes: The figure plots the percentage difference in bankruptcies in 2020 relative to 2019 (left panel), and 2021 Q1 and Q2 relative to 2019 Q1 and Q2 (right panel), by sectors. Sectors are converted from the original classification to ISIC rev. 4 sections when needed. Each bar reports a cross-country average based on data for Canada, Finland, Germany, Netherlands, Norway, Spain, and Sweden. For Spain, data for manufacturing include manufacturing and utilities (NACE rev. 2 sections C and N), and data for NACE rev. 2 sections K (Finance and Insurance) and R (Arts, Entertainment and Recreation) are not available. Data may be preliminary, experimental and subject to revision, and differ from official data.

Source: OECD calculations based on official sources: Canada, Canada Revenue Agency; Finland, Statistics Finland; Germany, Federal Statistical Office of Germany; Netherlands, CBS - Statistics Netherlands; Norway, Statistics Norway; Spain, Instituto Nacional de Estadistica; Sweden, Statistics Sweden.

While emergency measures may have prevented a wave of bankruptcies so far, they may also be only postponing it. When emergency measures are lifted, a possible sudden rise in bankruptcies would pose significant systemic risks. Exiting too early may therefore have detrimental effects for recovery, possibly advantaging large incumbent firms that are better prepared to weather the crisis and dampening competition. On the other hand, exiting too late may have negative implications for resource reallocation and long-term costs in terms of aggregate output and productivity if it is associated with a rise of zombie firms.

Despite the decline in bankruptcies, the recovery of firm entry in many countries suggests that the crisis and emergency measures may not have completely halted creative destruction. Governments can further limit the risks of zombification of the economy by choosing a balanced strategy to phase out emergency support policies.

Addressing long-term challenges is also key for recovery. Policymakers should ensure business-friendly frameworks, boost technology diffusion – with particular attention to digital and green technologies – and support workers’ transitions into new jobs, especially for more disadvantaged groups.

These policy actions together may bring double dividends for policymakers and strengthen the speed, sustainability and inclusiveness of the post-COVID-19 recovery (see also additional policy discussion in OECD 2021a, 2021b, Criscuolo 2021).

References

Bénassy-Quéré, A, B Hadjibeyli and G Roulleau (2021), “French firms through the COVID storm: Evidence from firm-level data”, VoxEu.org, 27 April.

Bighelli, T, T Lalinski and F di Mauro (2021), “Covid-19 government support may have not been as unproductively distributed as feared”, VoxEu.org, 19 August.

Buffington, C, D Chapman, E Dinlersoz, L Foster and J Haltiwanger (2021), “High frequency business dynamics in the US during the COVID-19 pandemic”, Working Papers 21-06, Center for Economic Studies, US Census Bureau.

Calvino, F, C Criscuolo and R Verlhac (2020a), “Declining business dynamism: Structural and policy determinants”, OECD Science, Technology and Industry Policy Papers No. 94.

Calvino, F, C Criscuolo and R Verlhac (2020b), “Start-ups in the time of COVID-19: Facing the challenges, seizing the opportunities”, VoxEu.org, 23 June.

Clementi, G L, and B Palazzo (2016), “Entry, exit, firm dynamics, and aggregate fluctuations”, American Economic Journal: Macroeconomics 8(3): 1–41.

Criscuolo, C (2021), “Productivity and business dynamics through the lens of COVID-19: The shock, risks and opportunities”, paper for the 2021 ECB Forum on Central Banking.

Demmou, L, et al. (2021), “Insolvency and debt overhang following the COVID-19 outbreak: Assessment of risks and policy responses”, VoxEu.org, 22 January.

Fareed, F, and B Overvest (2021), “Slowdown in business dynamics during the COVID pandemic: Empirical insights and lessons from the Netherlands”, VoxEu.org, 20 May.

Freeman, D, L Bettendorf and Y Adema (2021), “Covid-19 support distorted the process of creative destruction in the Netherlands”, VoxEu.org, 3 November.

Gourio, F, T Messer and M Siemer (2016), “Firm entry and macroeconomic dynamics: A state-level analysis”, American Economic Review 106(5): 214–18.

Kasinger, J, J P Krahnen, S Ongena, L Pelizzon, M Schmeling and M Wahrenburg (2021), “Preparing for a wave of non-performing loans: Empirical insights and important lessons”, VoxEu.org, 1 April.

OECD (2021a), “Business dynamism during the COVID-19 pandemic: Which policies for an inclusive recovery?”, OECD Policy Responses to Coronavirus (COVID-19).

OECD (2021b), Strengthening economic resilience following the COVID-19 crisis: A firm and industry perspective.

Sedláček, P (2020), “Lost generations of firms and aggregate labor market dynamics”, Journal of Monetary Economics 111: 16–31.

Sedláček, P, and V Sterk (2020), “Startups and employment following the COVID-19 pandemic: A calculator”, VoxEu.org, 25 April.

Endnotes

1 https://www.oecd.org/sti/dynemp.htm

2 This result is in line with recent studies on the role of the retail trade sector, and in particular online retail, in explaining the rise in business registrations, with evidence for instance for the Netherlands and the US (Buffington et al. 2021, Djankov and Zhang 2021, Fareed and Overvest 2021).

3 OECD (2021) further shows that the decline in entry during the first period of national lockdowns (the second quarter of 2020) was more pronounced in industries with a larger share of employment in occupations involving regular face-to-face contact with customers. In contrast, industries with a higher ICT task content of jobs have been relatively sheltered from the crisis, as evident from lower declines in entry in these industries.

4 One exception is Canada, where exit has significantly increased. This may be related to temporary closures captured in the data.

5 Replicating the analysis using medians instead of cross-country averages provides qualitatively similar results overall. The online visualisation tool allows us to explore these patterns in greater detail, focusing on specific countries, customised time periods and additional breakdowns of the data.