By the end of the summer, about half of US imports from China could be subject to import tariffs, with an average tariff of 11% (Bown et al. 2018). Hence, new tariffs will represent around 5% of total bilateral imports. Since the beginning of 2018, though, the Chinese renminbi has depreciated by 8% against the US dollar. Although the appreciation of the dollar is consistent with the US policy mix, some analysts have suggested that China could be tempted to manipulate its exchange rate to compensate for the imposed tariffs. Others have argued that the dollar would endogenously appreciate following the rise in import tariffs, with a neutral impact on the price competitiveness of US products.

While the impact of tariff and exchange rate changes are often discussed and compared in the policy debate, few papers have empirically compared the elasticities of exports to tariffs and to the exchange rate, except for a specific country (Fitzgerald and Haller 2014; Fontagné et al. 2017).

Tariffs are three times more ‘powerful’ than exchange rates

In a recent paper, we estimate these elasticities for a panel of 110 countries over 1989–2013 at the product (HS6) level (Bénassy-Quéré et al. 2018). We find that a 1% bilateral depreciation of the real exchange rate of the exporting country is associated with a 0.5% increase in the value of its bilateral exports, while a 1 percentage point cut in the import tariff in the destination country is associated with a 1.4% increase in bilateral exports. Hence, a 1% depreciation of the real exchange rate in the origin country is ‘equivalent’, in terms of exports, to a 0.34 percentage point tariff cut in the destination country – the tariff cut is about three times more ‘powerful’ than an exchange-rate depreciation. There is no equivalence between both instruments as far as trade flows are concerned.

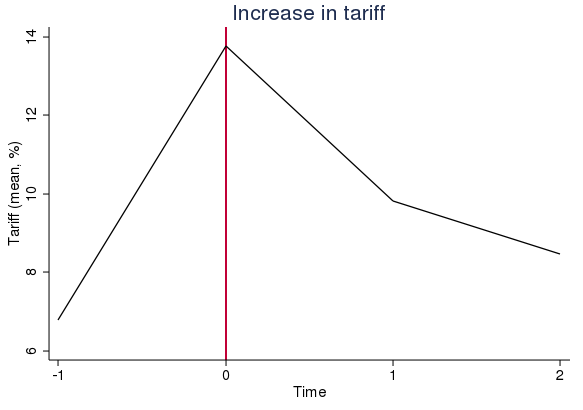

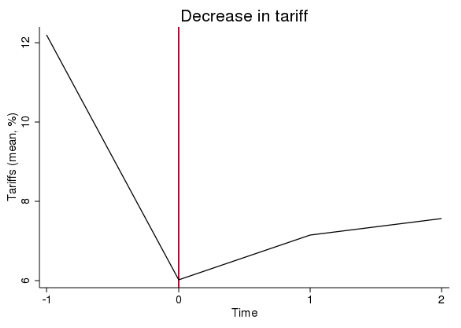

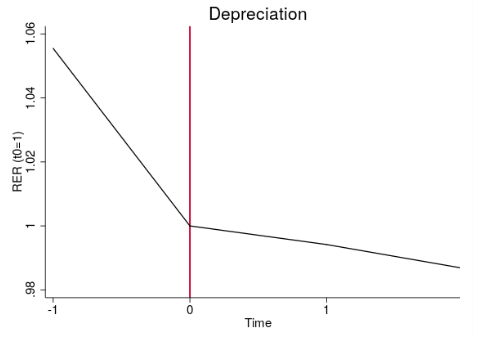

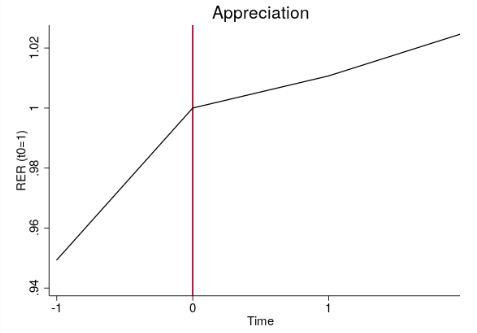

This empirical asymmetry is consistent with the elasticities found separately in the literature for tariffs and for the exchange rate (Head and Mayer 2014). Its causes are not clear-cut, though. The most immediate explanation would be that tariffs are decided by governments whereas exchange rates are generally determined by markets. Thus tariffs changes are expected to be more long-lasting than exchange-rate variations. As illustrated in Figure 1, this first explanation is not fully convincing. A tariff hike is in fact less persistent than a real exchange-rate appreciation or depreciation.

Figure 1 Average lifespan of tariff and real exchange rate variations (bilateral)

Note: Time 0 corresponds to the year of the tariff increase or cutand to the year of the real exchange rate appreciation or depreciation (compared to time -1).

Source: Bénassy-Quéré et al. (2018).

Another possible explanation for different elasticities could be that the exchange rate is endogenous to tariff variations – a tariff hike in the importing country would be concomitant to an exchange-rate appreciation, and the collinearity between the two variables would bias the estimations. This second explanation is not convincing either, since our estimations show that the exchange rate reacts only with a lag to tariff changes.

Perhaps the result has more to do with general equilibrium effects. The real exchange rate of a country will generally appreciate when the economy is booming and the central bank is tightening monetary policy. In contrast, tariff hikes are a government decision, and the pressure to impose tariffs in imports may be greater when the economy is depressed. More research is needed to understand why the elasticities on tariffs and on the exchange rate differ so much.

Trade or currency weapons?

Applying our estimates to the trade conflict between the US and China, one would conclude that a 14% depreciation of the renminbi against the US dollar would be necessary to erase the effect of a 5 percentage point average increase in US import tariffs. For larger tariff hikes, the compensating exchange variation becomes extremely large and destabilising.

However, the whole idea of neutralising the impact of tariffs on trade flows is odd in terms of policymaking. In the long term, import tariffs have a negative impact on GDP and on average welfare, while the real exchange rate can hardly be manipulated. In the short run, an import tariff could be used in a downturn to stimulate the domestic economy, but in normal times, it is inferior to monetary policy that works not only through the external channel, but also through the domestic channel.

Although tariffs are three times more ‘powerful’ than exchange rates in reducing imports (and raising the trade balance), this must not hide the fact that monetary (and exchange rate) policy is much more powerful than tariffs when it comes to stabilising aggregate demand, and it has no negative impact in the long run.

References

Bénassy-Quéré A, M Bussière and P Wibaux (2018), “Trade and currency weapons,” CESifo, Working Paper Series 7112.

Bown, C, E Jung and Z Lu (2018), “Trump's $262 billion China tariff threat plays with the bank’s money,” Peterson Institute for International Economics, Blog Post, 24 July.

Fitszgerald, D and S Haller (2014), “Exporters and shocks: Dissecting the international elasticity puzzle,” NBER, Working Paper 19968.

Fontagné, L, P Martin and G Orefice (2017), “The international elasticity puzzle is worse than you think,” CEPII Working Paper 2017-03.

Head, K and T Mayer (2014), “Gravity equations: Workhorse, toolkit, and cookbook”, Handbook of International Economics.