The financial crisis is wreaking havoc on the global economy. In the first quarter of 2009, nominal trade fell by 30% on average since last year. The world trade volume is estimated to have fallen by 18% during this period (World Trade Monitor 2009). The declines have been widespread across countries and products, largely reflecting the sharp drop in global demand.

We examine historical data on global slowdowns to look for similarities that may offer insights into the large decline in trade that has already begun. There are four such events in recent history: 1975, 1982, 1991, and 2001.1

While these events were on average modest compared to the current crisis, they may offer some guidance for what to expect in the coming months. We focus on global downturns, as opposed to financial crises, because these share the current environment&rsquos key characteristic (for international trade) of low global demand with the current environment.2 In contrast, during regional financial crises, demand in the rest of the world tends to remain strong, limiting the trade impact of the crisis.

We also examine a handful of countries, which experienced financial crises during the 1991 global downturn, in order to determine whether banking crises significantly exacerbate weak trade performance during slowdowns.

Key findings on the historical episodes

The first issue we address is how much does trade contract when the global economy falters? We find that (see Freund 2009a for details):

- The trade contraction follows the GDP decline and that the trade volume declines by about 1% on average in the first year of its contraction.

- The decline in the growth rate of trade (from historical average to trough) is sudden and is on average more than 4 times as large as that of income.

- On average, trade growth returns as quickly as it disappears and contemporaneously with the rebound in GDP growth.

- Still, it takes more than three years for pre-downturn levels of openness to be reached.

As a result of the collapse in trade, crises moderate global imbalances. Since trade contracts by more than GDP, a country’s trade balance as a share of GDP (whether surplus or deficit) typically declines in absolute value. Moreover, because of falling commodity prices during downturns, the deceleration in trade value tends to be far greater than in trade volumes. We show that the reversal of trade deficits tends to persist for Asia, Europe, Latin America, and the Middle East. In North America, the improvement in the trade balance has been temporary, with deficits worsening following the downturn. In contrast, surplus regions tend to see only a temporary reversal.

The results have important implications for trade during the current financial crisis. Given current GDP forecasts and trade data available through June, our results imply that the decline in real trade in 2009 could well exceed 15%. In addition, global imbalances are likely to be mitigated during the crisis, and this may persist even after the crisis is resolved.

Methodology

Following Milessi-Ferretti and Razin (1998) and Freund (2005) on current account reversals, we use a filter to identify episodes of global downturns. Specifically, a global downturn must satisfy the following criteria:

- World real GDP growth below 2%.

- A drop of more than 1.5 percentage points in world real GDP growth from the previous 5-year average to current rate.

- Considering the previous 2 years and the following 2 years, growth is at a minimum.

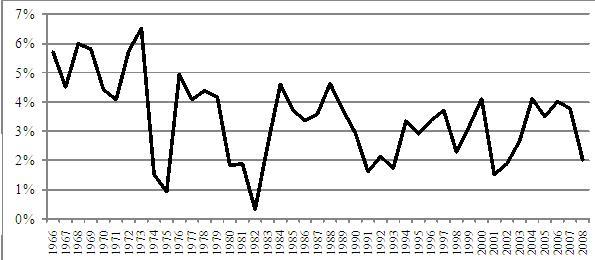

The first two conditions ensure growth is low and has dropped sharply. If the first two conditions identify consecutive years, i.e. prolonged recessions, the final condition chooses the minimum growth rate as the event year. Using data on real GDP (in constant $US, base year 2000) and real imports (in constant $US, base year 2000) from the World Development Indicators since 1960, four events are identified: 1975, 1982, 1991, and 2001. These events are readily seen as the sharp downturns in Figure 1. In the remainder of this note, the downturn year is denoted as year zero.

Figure 1 Real GDP Growth

Source: World Bank, World Development Indicators.

What happens to trade during downturns?

To estimate trade effects of recessions, we need an estimate of the elasticity of trade to income – the ratio of the percentage change in trade over the percentage change in income.

Most forecasters use an elasticity of about 2, i.e. real trade growth should grow by 2 percentage points for each 1 percentage point deceleration in real income growth.3 This leads to relatively small estimates of the decline in trade relative to what we have seen. For example, in January 2009, the IMF predicted a 2.8% decline in real trade (IMF (2009). In June, the World Bank revised its March forecast from a 6.1% decline to a 9.7% decline, after reducing sharply its forecast for global growth (World Bank 2009). The World Bank estimates are larger because it predicts a larger decline in incomes and includes the potential effects of trade finance problems.

Freund (2009b) re-examines the relationship between trade growth and income growth and finds that the elasticity of trade to income has increased from under 2 in the 1960s to over 3½ (also see Irwin 2002). Overall, the results imply that trade should fall (in %) about 3½ times as much as GDP, assuming crises are not special.

Global supply chains and lean retailing as fundamental shifts

The significant increase in the elasticity of trade to income may be attributed to the fragmentation of production and/or lean retailing. Because many new goods use small inputs that are nearly costless to trade (e.g. cell phones and digital cameras), the production process of these goods has become fragmented across countries. Many traditional goods such as shoes and cars are also increasingly incorporating imported inputs. The elasticity of trade to GDP will rise if there is more incentive to outsource part of the production chain when demand is high. This is because GDP is measured in value added while trade is a gross measure. So an increase in GDP may lead to more outsourcing and much more measured trade, as an increasing number of parts travel around the globe to be assembled, and then again to their final consumer.

The expansion of lean retailing in recent years implies that supply responds almost immediately to changes in demand. Rapid technological advances make computers and other electronics almost perishable, and many companies have started selling straight to the consumer and producing only for realized demand. For example, Dell sells directly to its customers and builds a made-to-order computer as orders arrive (Arthur 2006, Chapter 2, p. 25). This type of retailing implies that a drop in demand will show up immediately in trade statistics.

Freund (2009a) examines the elasticity of a region’s exports to global income. The intuition for looking at regional trade and global income (instead of regional income) is to see how tied a region’s exports are to the global economy.

To the extent that the increase in the world elasticity of trade to income is a result of greater fragmentation we should see especially large numbers for East Asia. Indeed, with an elasticity of 4½. East Asia records the largest elasticity in the recent period, as well as the largest increase in elasticity, suggesting that fragmentation of production is in part responsible. It also implies that East Asia may be the most affected region during the current downturn but among the first to pull out when conditions improve.

The growth in the elasticity in this region is also likely connected to China’s phenomenal growth in assembly of manufactures over the period. Still, as the OECD is responsible for the bulk of world trade, the global elasticity also closely mirrors that of the OECD. In contrast, trade in the low-income countries does not significantly respond to world income.

Trade-GDP response during global downturns

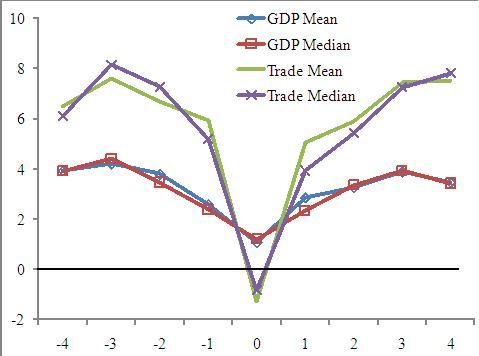

Figure 2 shows real trade growth and real GDP growth in the years around the previous global crises.

Figure 2 Real world trade and real GDP growth rates in crises.

Note: Years before and after the nadir year for each of the four crises. Source: World Bank, World Development Indicators (see Freund 2009a for details).

We report the mean and the median to ensure that results are not driven by an outlier. While income growth falls to 1.5%, trade tends to decline by about 1%. (Real trade growth was negative only in 1975 and 1982.) In addition, the decline in growth from the previous year to the crisis year is much larger for trade. GDP growth declines on average by 1.5 percentage points from previous year, while real trade declines on average by 7.2 percentage points, nearly 4.7 times as much. If during this downturn, we see a similar ratio there would be a decline of about nearly 20% in real trade this year, given the World Bank’s current GDP forecast.4

These results imply that trade responds more sharply to GDP during global slowdowns than during tranquil times. There are a number of potential explanations:

- Firms may draw down accumulated inventories sharply when the forecast worsens in an unexpected and dramatic way.

- When global GDP drops sharply, protectionist policies kick in which exacerbate the decline in trade.

- During downturns, goods decline by more than services and services make up the bulk of GDP, while goods make up the bulk of trade.

Moreover, the share of services in GDP has increased over time, magnifying this distinction.

- Trade is measured in gross value and GDP in value added.

A large decline in trade could reflect a much smaller decline in the value added if production is done across countries at the margin and, as demand falls, international production chains break down.5

- People may tend to source relatively more from home country suppliers during downturns because of trust or financing problems, or simply because many imports serve excess demand in good times.

On the positive side, we find that trade tends to achieve most of its adjustment in a single year also when it rebounds. The quick rebound likely reflects the reversal of many of the conditions above. Figure 3 looks at trade’s share of income over the episodes to see how global openness changes over time. We find that it takes about 4 years for trade to pass pre-downturn levels.

Finally, we examine whether countries with banking crises are affected more severely or differently during a downturn. We focus on three countries – Finland, Sweden, and Japan – that experienced severe banking crises around 1991, when there was also an episode of slow world income growth.6

The results – see Freund (2009a) for details – show that income and imports fell much more sharply for the crisis countries than for the rest of the world. Exports fell by just about the same amount as world trade, suggesting that the aggregate exports of the crisis countries were no more affected by the global downturn than exports in the rest of the world.7 Exports rebounded far more rapidly than income, rejoining world growth rates after just one year. Even imports expanded more than one-third of the full amount in the first year after the downturn began, despite negative income growth. All three variables, exports, imports, and GDP, returned to average world growth levels after 3 years. This suggests that the relatively quick rebound in trade remains intact in financial crisis countries.

How are trade balances affected?

Given that trade falls more than income, it is likely that global imbalances as a share of GDP improve. This will be true unless exports fall by much more than imports in deficit countries and imports fall by much more than exports in surplus countries. In this section, we examine whether there is an improvement in global imbalances and whether it is short-lived or persistent.

To evaluate global imbalances we examine the trade balance as a share of GDP across regions and income groups, and also whether the countries tend to be surplus or deficit countries.

Figure 3 Aggregate trade balance – deficit countries (% of GDP)

Source: World Bank, World Development Indicators.

Figure 4 Aggregate trade balance – surplus countries (% of GDP)

Source: World Bank, World Development Indicators.

Figure 3 and 4 show movements in the aggregate trade deficit and surplus for international borrowers and lenders, respectively. Specifically, Figure 3 is the aggregate trade deficit relative to GDP over time of all the countries that had a deficit before the downturn.8 Similarly, Figure 4 is the aggregate trade surplus relative to GDP over time of all the countries that had a surplus before the downturn. On aggregate, there is only a temporary improvement, and the position quickly returns to where it was before the episode. This suggests that there is not an overall rebalancing between pre-downturn surplus countries and pre-downturn deficit countries.

However, the pictures are very different when we look across regions (Figures 5 and 6) or income groups (Figures 7 and 8).

Figure 5 Aggregate trade balance – deficit countries by region

Source: World Bank, World Development Indicators.

Figure 6 Aggregate trade balance – surplus countries by region

Source: World Bank, World Development Indicators.

Figure 7 Aggregate trade balance – deficit countries by income level

Source: World Bank, World Development Indicators.

Figure 8 Aggregate trade balance – surplus countries by income level

Source: World Bank, World Development Indicators.

We find that in Latin America, East Asia, Europe and the Middle East, and North Africa, there is a tendency to reduce sharp deficits following downturns. These are regions where the imbalances were deemed dangerous, and the government put policies in place to ensure they did not re-emerge. These included savings’ incentives and maintaining an undervalued exchange rate to strengthen the BOP position. In addition, weakened firm fundamentals during a global downturn may induce a drop in investment.

In contrast, North America tends to show a relatively stable account that improves slightly during the downturn, but worsens in its aftermath. This may reflect the flexibility of the U.S. economy and the safety of dollar assets. This may also be related to the downturns not having been severe enough to change U.S. government policies and firm fundamentals, as happened in middle-income and developing borrower countries.

Surplus countries, by contrast, in general show only temporary reversals. Unlike deficit countries, where there may be pressure to change policies and investment behaviour following a costly recession and capital outflow, surplus countries do not experience such an impetus for change.

Conclusion and looking forward

Trade has fallen dramatically since the onset of the financial crisis. Figure 8 compares trade growth (month over same month the previous year) in this crisis and in the previous downturns, using monthly data in constant $US, for a balanced sample of 31 countries that report data from 1960 - March 2009.9

While growth leading up to the crisis was a bit higher in this episode, it still looked quite similar to the previous downturns. What is most evident from the picture is that the trade drop over the last few months has been much steeper and more severe than other recent episodes. Perhaps of greatest import now is that the rebound also looks like it may be rapid.

Figure 9. The decline in trade now and then.

Source: Datastream. Data in $US for a balanced sample of 31 countries, deflated using the US CPI.

Concluding remarks

This chapter – based on an update of Freund (2009a) – offers some background on why the trade drop has been so large.

We argue that the elasticity of trade to income has been increasing over time and that trade is especially responsive to income during recessions. On the positive side, we note that trade tends to rebound sharply when growth picks up. Given especially high elasticity of exports to world income in Asia, it is not surprising that trade is now expanding rapidly in the region. The swift turnaround in trade is similar to the result in Reinhart and Rogoff (2008) that output declines resulting from a financial crises last only two years, as compared with about four years for employment and equity drops.

We have also seen that downturns tend to moderate global imbalances. However, the moderation tends to be temporary unless the downturn alters investment attitudes and/or government policies. Given that the downturn will get the process started, we hope that governments can use the transition to install policies that will ensure that imbalances do not revert to pre-crisis trends. This will include policies to encourage saving in the US and prevent an overvalued dollar, and policies to stimulate spending in China and other parts of Asia and prevent undervalued currencies.

Footnotes

1 The research on which this chapter is based was supported by funding from PREM Trade and is part of a World Bank research project on exports and growth supported in part by the governments of Norway, Sweden and the UK through the Multidonor Trust Fund for Trade and Development. I am very grateful to Matias Horenstein for excellent research assistance and to Simeon Djankov, Thomas Farole, Leonardo Iacovone, and Juan Sebastien Saez for comments on an earlier draft of this paper. This article reflects the views of the author and not the World Bank.

2 The approach is similar in spirit to Reinhart and Rogoff (2008), who examine previous financial crises for information on the macroeconomic implications of the current crisis. While our focus on global downturns and international trade is quite different from, there is one important similarity in our results. Our results point to a sharp but relatively short-lived decline in trade, akin to what they find for output. A significant difference is that unlike the expanding government debt they observe, we find that international borrowers often reduce international debt following global downturns.

3 A number of papers have estimated income elasticities of imports or exports for individual countries and generally find them to lie between 1 and 3½ (see, for example, Hooper et. Al 2000 and Kwack et. Al. 2007).

4 Using an elasticity of trade to income during the downturn of between 4.7 and a deceleration in real world income growth of 4.8 percentage points (the World Bank estimate), the deceleration is real trade growth would be 23 percentage points. World real trade growth in 2008 was about 4%, yielding a contraction this year of 19%.

5 An example of this is Porsche which is cutting outsourcing to Finland during the crisis, while maintaining German production (New York Times, April 4, 2009). Note that increasing vertical specialization can explain why trade has expanded faster than income in recent years, but a higher level of vertical specialization cannot explain why the elasticity of trade to income is higher.

6 Finland 1991, Sweden 1991, and Japan1992 are included in the “big five” crises, the other two are Spain 1977 and Norway 1987.

7 Iacovone and Zavacka (2009) find that there are compositional effects of banking crises on exports. Export growth in sectors that depend relatively more on external finance declines relative to growth in other sectors in the aftermath of the crisis.

8 Specifically, we use the value of deficit or surplus four years before the episode to characterize country as a surplus or deficit country. Data are from the IMF BOP Statistics for a balanced sample of countries reporting.

9 Month zero is the minimum trade growth during previous downturns. The series for the current period is matched to previous downturns using the minimum trade growth. Specifically, the minimum trade growth is superimposed over the minimum trade growth on average in the previous downturns.

References

Arthur, J. (2006) Lean Six Sigma Demystified. McGraw Hill Professional.

Freund, C (2009a) “The Trade Response to Global Crises: Historical Evidence” World Bank working paper.

Freund, C. (2005) “Current Account Adjustment in Industrial Countries” Journal of International Money and Finance 24, 1278-1298.

Freund, C. (2009b) “Demystifying the collapse in trade” VoxEU.org, 3 July 2009.

Hooper, P., K. Johnson, & J. Marquez (2000). Trade Elasticities for the G-7 countries. Princeton Studies in International Economics 87(August).

Iacovone, L. and V. Zavacka. (2009). "Banking Crises and Exports: Lessons from the Past." Policy Research Working Paper Series 5016. The World Bank, Washington, D.C.

IMF (2009). “World Economic Outlook Update: Global Economic Slump Challenges Policies," January 28, 2009.

Irwin, D. (2002) “Long-Run Trends in World Trade and Income” World Trade Review 1: 1, 89–100.

Kwack, S. Y., C.Y. Ahn, Y.S. Lee, D.Y. Yang (2007). “Consistent Estimates of World Trade Elasticities and an Application to the Effects of Chinese Yuan (RMB) appreciation”. Journal of Asian Economics 18: 314–330

Milesi-Ferretti, G. and A. Razin (1998) “Sharp Reductions in Current Account Deficits: an Empirical Analysis” European Economic Review 42, April 1998, 897-908.

Reinhart, C. and K. Rogoff (2008) “The Aftermath of Financial Crises” Mimeo, Harvard University.

World Bank (2009). “Prospects for the Global Economy”, Global Development Finance 2009”.

World Trade Monitor & League of Nations (2009).