Editors' note: This column is part of the Vox debate on the economic consequences of war.

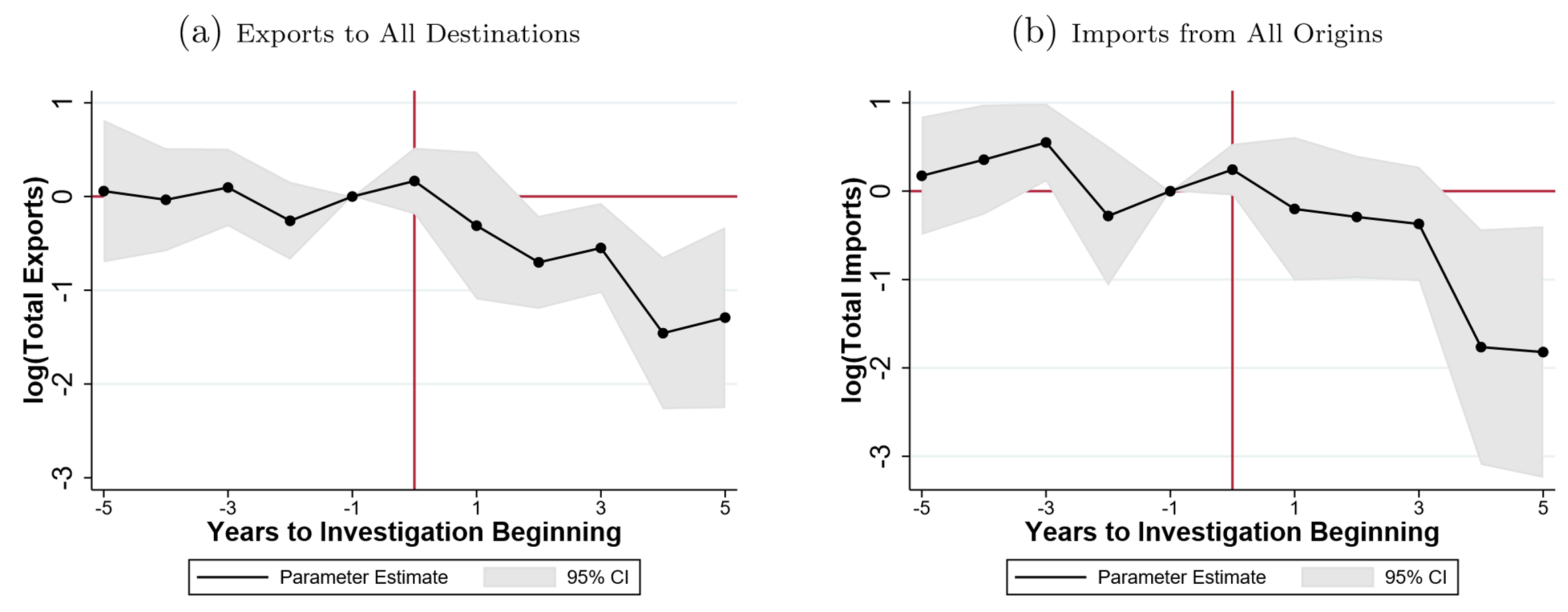

Since the invasion of Ukraine, several countries have imposed trade sanctions against Russia. Sanctions, such as tariffs or embargoes, are a double-edged sword. On the one hand, they can reduce Russia’s war capability. On the other hand, they may harm the sanctioning countries’ economies. In a recent paper (de Souza et al. 2022), we first demonstrate that tariffs against Russia hurt both the sanctioning country and Russia, so that the former faces a tradeoff between economic losses in Russia and its own country. Using the difference-in-difference strategy developed in de Souza and Li (2020), we show that tariffs against Russia strongly decrease Russia’s total exports (Figure 1a). This result indicates that, after an increase in tariffs, Russia cannot find alternative buyers for its products. Consequently, Russian income falls.

However, a tariff against Russia also decreases the sanctioning country’s total imports of the targeted product (Figure 1b). That indicates the sanctioning country also cannot easily find substitutes for Russian products. Therefore, tariffs against Russia hurt both Russia’s economy and the sanctioning country’s economy.

Figure 1 Impact of anti-dumping tariffs on product-level total exports and total imports

Note: This figure shows the dynamic impacts of anti-dumping tariffs on total exports by Russia and total imports by the country that imposes the tariff, both in the targeted product.

Willingness to pay for sanctions

To calculate cost-efficient sanctions, we build a quantitative model of international trade with input-output linkages. The model extends the work by Ossa (2014) and Caliendo and Parro (2015). Countries choose tariffs to maximise their own income and minimise Russia’s income, with different weights on these objectives. If countries put a high weight in minimising Russia’s income, they are more willing to give up on its own income in order to achieve that goal. In this case, we say that countries have a high willingness to pay for sanctions.

Which sectors should sanctions target?

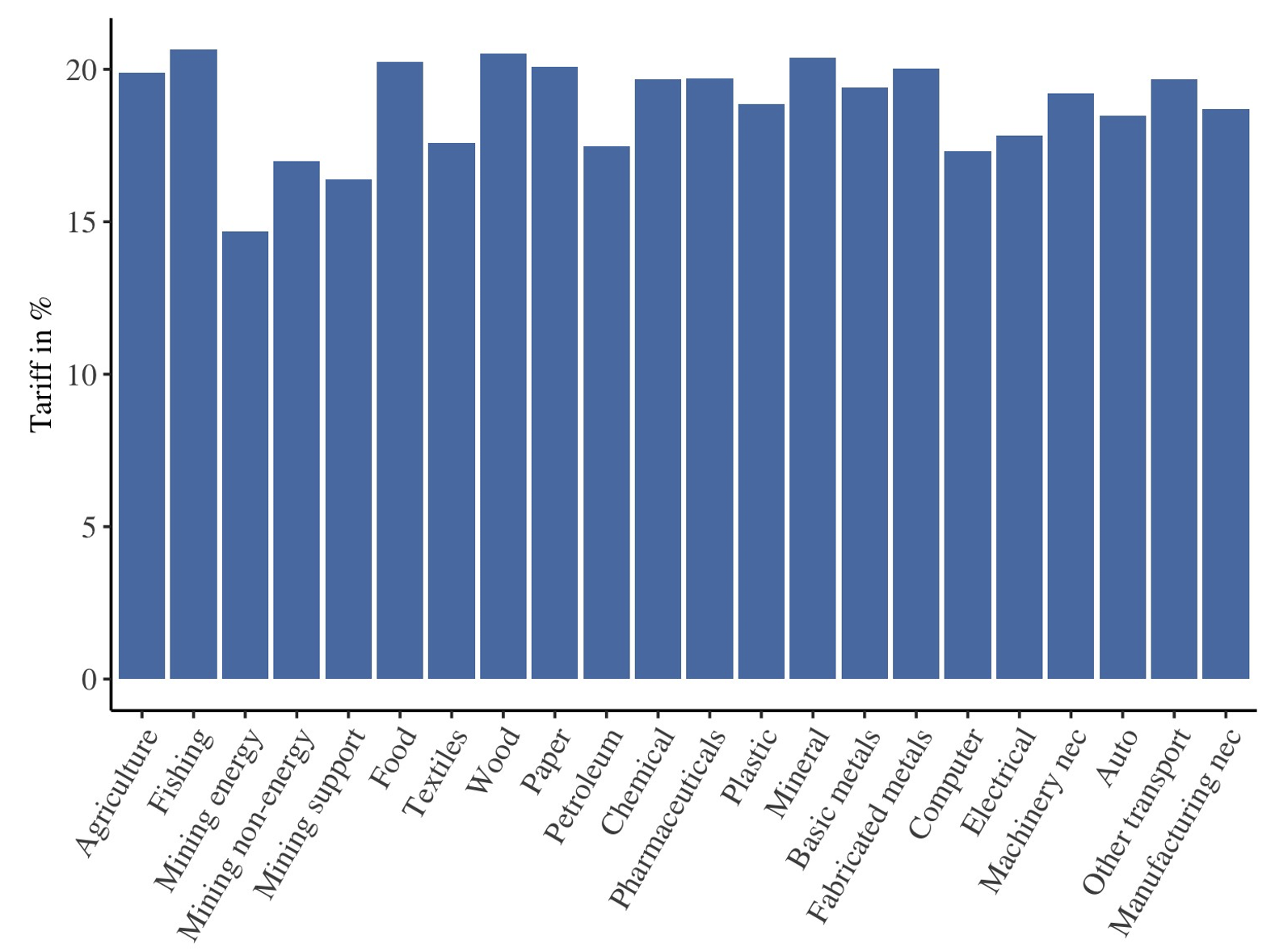

If countries are not very committed to sanctioning Russia, that is, they have low willingness to pay for sanctions, the optimal strategy is a uniform tariff on all Russian products of about 20%. Figure 2 shows the optimal tariffs by the EU if the EU is only willing to pay $0.10 to reduce Russian Gross National Income (GNI) by $1. We predict that this trade policy would decrease GNI by 0.8% in Russia without any significant cost to the EU or the US.

If countries are more serious about sanctions and are willing to sacrifice at least $0.70 for each $1 drop in Russian consumption, embargoes on Russia’s mining and energy products – with tariffs above 50% on all other products – is the optimal policy.

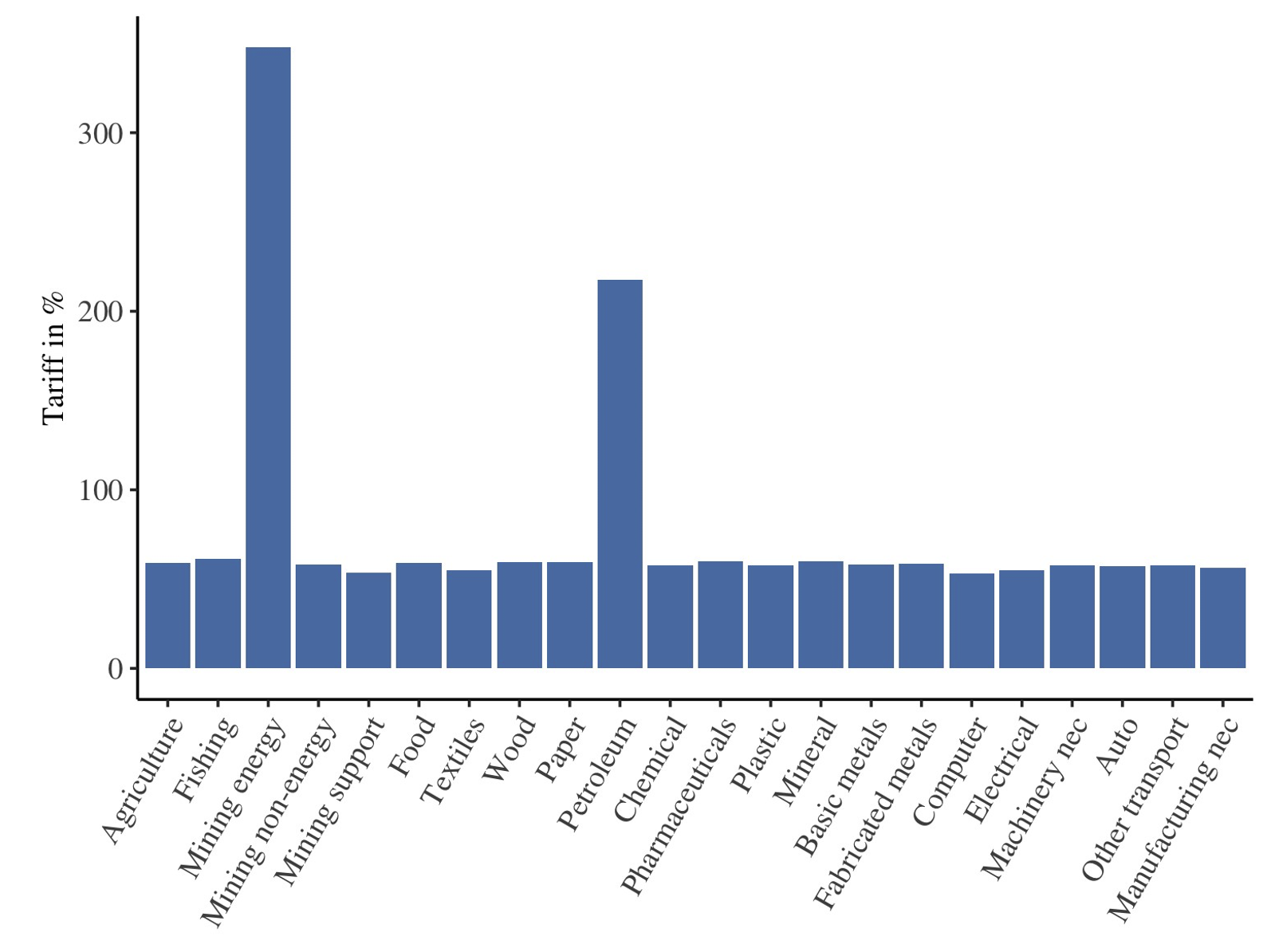

Figure 2 Optimal sectoral tariffs imposed by the EU if the EU’s willingness to pay for sanction equals $0.10

Note: This figure shows the optimal sectoral tariffs that the EU imposes on Russia if the EU is willing to pay $0.10 to reduce Russian GNI by $1.

The intuition for these results lies in the fundamentals of the model. If countries choose tariffs to maximise their own welfare, lower tariffs should be placed on the sectors (1) whose products they import less and (2) that have lower trade elasticities (see e.g. Broda et al. 2008). When there’s a low willingness to pay for sanctions, these two incentives cancel each other out, leading to low and similar tariffs across sectors. However, if countries use tariffs to punish their trade partners, higher tariffs should target the sectors (1) whose products they import more and (2) that have higher trade elasticities, because they can reduce Russia’s output more. Because mining and energy products account for more than half of Russian exports and these two sectors’ trade elasticities are at the higher end of all sectors, the sanctioning countries find it optimal to impose embargoes on these two sectors’ products from Russia.

Which country can inflict more economic damage on Russia?

The EU is the country group whose sanctions cause the most economic damage in Russia. Because Russia exports more to the EU than to any other sanctioning country, the EU alone can reduce real income in Russia by 0.8% at a welfare cost of 0.1% to the EU.

Figure 3 Optimal sectoral tariffs imposed by the EU if the EU’s willingness to pay for sanction equals $0.70

Note: This figure shows the optimal sectoral tariffs that the EU imposes on Russia if the EU is willing to pay $0.70 to reduce Russian GNI by $1.

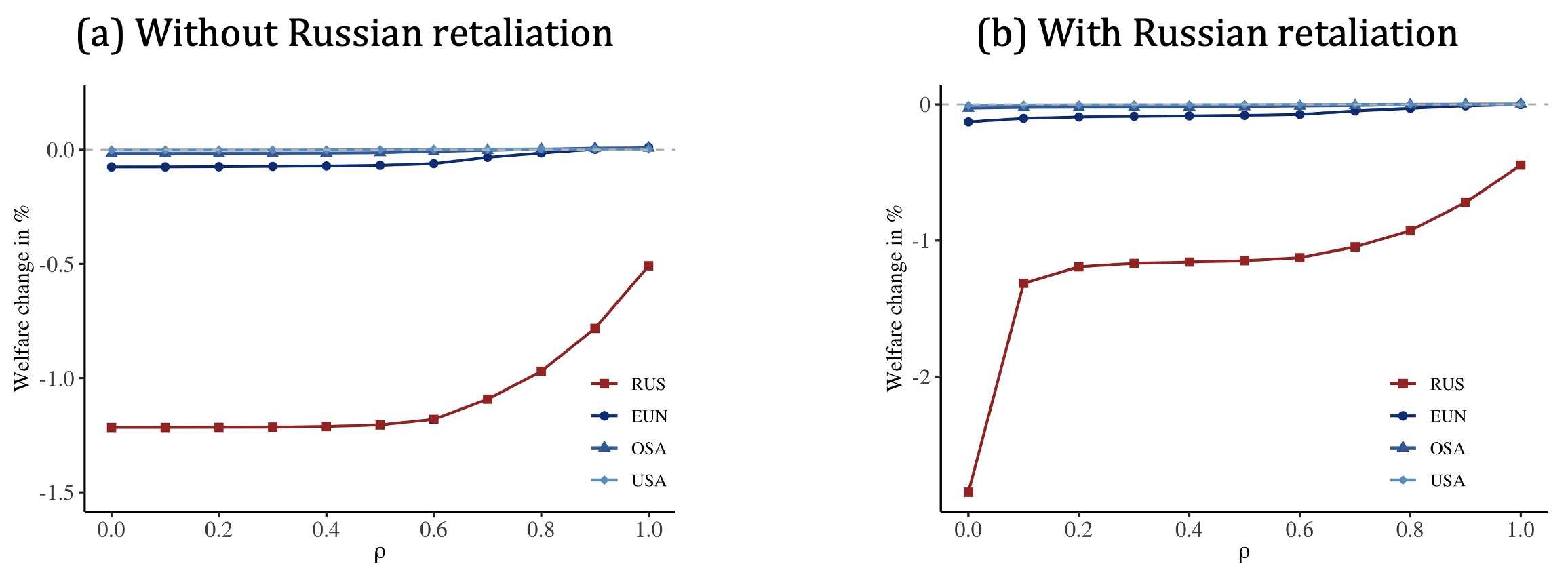

If the EU, US, and other sanctioning countries sanction Russia jointly, the group sanction can reduce Russia’s real income by as much as 1.2% (Figure 4a).

Retaliatory tariffs by Russia can slightly increase the welfare cost of sanctions to the sanctioning countries. However, their sanctions more than double Russia’s real income loss to 3% (Figure 4b). Because of the economic size difference between the sanctioning countries and Russia, the sanctioning countries are an important importing origin for Russia, but Russia is not an important exporting destination for the sanctioning countries. Therefore, Russia imposing high tariffs cannot decrease the sanctioning countries’ welfare much, but this causes a large decline in Russia’s own welfare.

How should sanctions be imposed if they target the politically connected sectors?

Results change drastically if the objective of sanctions is to attack Russian political elites rather than normal Russian citizens. We find that, even with a low willingness to pay for sanctions, embargoes on Russia’s mining and energy products should be implemented if the objective of sanctions is to target Russian oligarchs.

Figure 4 Welfare changes with and without Russian retaliation

Note: This figure shows the welfare change in Russia and in sanctioning countries under different willingness to pay for sanctions and two model variations: Russia does not retaliate (Figure 4a) and Russia retaliates with the same willingness to pay for sanction (Figure 4b). The willingness to pay for sanctions equals (1 − ρ)/ρ, that is, countries would like to pay $(1 − ρ)/ρ to reduce Russia’s real income by $1.

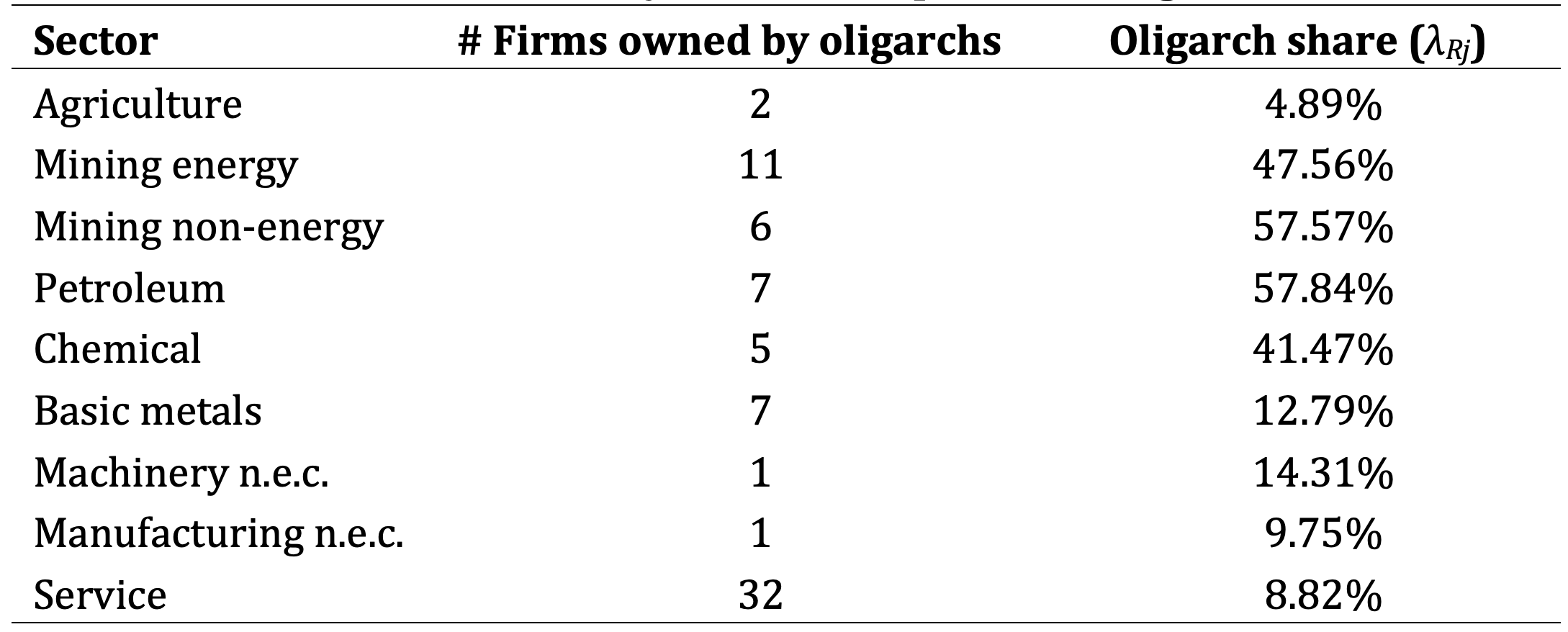

To determine a sector’s political relevance, we link every individual sanctioned by the EU, US, or UK, referred to as ‘an oligarch’, with the companies that they own. Then we compute, for each sector, the sales share of these companies in the sector’s gross output.

Because oligarchs are concentrated in the mining and energy sectors (Table 1), even if countries do not want to sacrifice much of their own economy to sanction Russia, they can significantly hurt the welfare of Russian elites with an embargo on mining and energy sectors.

Table 1 Summary statistics of political weights

Note: This table presents summary statistics of the political weights. The table shows, in each sector, the number of top 500 Russian firms owned by Russian oligarchs and the revenue share generated by these firms.

Conclusion

We find, first, that for countries with a small willingness to pay for sanctions against Russia, the most cost-efficient sanction is uniform, at around a 20% tariff against all Russian products. This tariff policy is similar to what some countries have already implemented and has been advocated by some economists (Sturm 2022, Gros 2022) Second, if countries are willing to pay at least $0.70 for each $1 drop in Russian welfare, an embargo on Russia’s mining and energy products – with tariffs above 50% on other products – is the most cost-efficient policy. Finally, if countries target politically relevant sectors, an embargo against Russia’s mining and energy sector is a cost-efficient policy even when there is a small willingness to pay for sanctions. These results highlight that, regardless of the objective of sanctions, if the EU is committed to sanctioning Russia, an embargo in oil and gas is the most cost-efficient policy, as has been advocated by several economists (Chepeliev et al. 2022, Hosoi and Johnson 2022, Vaitilingam 2022)

References

Broda, C, N Limao and D E Weinstein (2008), “Optimal tariffs and market power: the evidence”, American Economic Review 98(5): 2032–65.

Caliendo, L and F Parro (2015), “Estimates of the trade and welfare effects of NAFTA”, The Review of Economic Studies 82(1): 1–44.

Chepeliev, M, T W Hertel and D van der Mensbrugghe (2022), “Cutting Russia's fossil fuel exports: Short-term pain for long-term gain”, VoxEU.org, 9 March.

de Souza, G, N Hu, H Li and Y Mei (2022), “(Trade) war and peace: How to impose international trade sanctions”, Working paper.

de Souza, G and H Li (2020), “The employment consequences of anti-dumping tariffs: Lessons from Brazil”, Working paper.

Gros, D (2022), “How to solve Europe's Russian gas conundrum with a tariff”, VoxEU.org, 30 March.

Hosoi, A and S Johnson (2022), “How to implement an EU embargo on Russian oil”, VoxEU.org, 20 April.

Ossa, R (2014), “Trade wars and trade talks with data”, American Economic Review 104(12): 4104–46.

Sturm, J (2022), “The simple economics of a tariff on Russian energy imports”, VoxEU.org, 13 April.

Vaitilingam, R (2022), “Economic consequences of Russia's invasion of Ukraine: Views of leading economists”,VoxEU.org, 10 March.