The Federal Reserve Bank of New York, the European Commission, and CEPR jointly organised a conference on “Transatlantic Economic Policy Responses to the Pandemic and the Road to Recovery”, on 18 November 2021. The conference brought together US- and European-based policymakers and economists from academia, think tanks, and international financial institutions to discuss issues that transatlantic policymakers are facing. The conference was held before the Russian invasion of Ukraine and the global monetary tightening. Still, its medium to long-term focus provides interesting insights on economic policy challenges ahead.

Several questions were addressed by the panellists: What can be done to support growth, while addressing inflationary pressures, facilitating the climate transition, and reducing economic inequalities? What are the key changes in the Federal Reserve and ECB new monetary policy frameworks? At which speed should the US and the EU consolidate their public finances and what roles should be played in the future by automatic stabilisers and fiscal rules? In this column, we summarise the principal themes and findings of the conference discussion.

Panels 1 and 2: “Post-pandemic policy challenges over the medium and long term”, and “Debt sustainability and international financial spillovers after the pandemic”

With respect to medium- and long-term policy challenges, panellists considered both those from the pre-pandemic world (for example, high debt levels, rising inequalities, climate change) and new ones (for example, future pandemics, health care systems).

Panellists noted that the COVID-19 pandemic had some unexpected effects on inequalities. It did not have a big impact on income inequality, as workers – in particular, those with lower incomes – benefited from government support measures. On the other hand, the low interest rate environment triggered a very strong increase in asset prices, significantly exacerbating wealth inequalities.

As for public finances, in advanced economies debt levels rose in some cases to record highs. But interest rates were low and were expected to stay relatively low for some time, moderating short-term concerns about debt sustainability and reducing the risk of having to impose austerity measures. Still, high public debt significantly reduced fiscal space in many countries.

To deal with both inequalities and debt levels, panellists considered that taxes would have to be raised. Recently there had been some positive developments on the taxation front, for instance the agreement on international corporate taxation (although it should be considered not the end point of a process, but rather the beginning of something that could become much bigger). However, more was needed: a much greater effort should be put in closing tax loopholes, fighting tax evasion and decreasing tax avoidance. Moreover, one panellist asserted that the wealthiest should be taxed more, although it remained to be seen whether this would be politically feasible, particularly in the US.

On climate change, panellists noted that the world did not yet have the technology to fully tackle it. In any case, technology alone would not solve the problem. Global warming challenges were not just about ingenuity and technology, as they also required significant changes in societies’ behaviour, making them also macroeconomic and political issues. The cost of the climate transition would be macroeconomically significant. Therefore, income support was needed to mitigate the impact of the transition on low-income groups. Carbon taxes could enable policymakers to spend money effectively in the green transition.

As for health challenges, panellists observed that the handling of COVID-19 at the global level had not been a good example of multilateral cooperation, in particular the distribution of vaccines to developing countries. Looking forward, it was crucial for the EU and the US to find ways to cooperate with other countries, including China, to address the pandemic-related challenges, as they cannot be solved without international cooperation.

Panellists also argued that governments will have to spend heavily in coming decades to modernize infrastructure, strengthen health care systems, and decrease inequalities. Thanks to the decisive response to the pandemic, governments, and institutions had regained some of the credibility lost in the aftermath of the global financial crisis and now have more political capital to deal with these challenges. As one panellist put it, pandemics and climate change have the potential to change the way in which the challenges ahead are perceived as ‘existential wars’. And in ‘war times’ extraordinary measures may be acceptable by citizens if the war must be won.

Fireside chat: The New Federal Reserve and ECB strategies – implications for monetary policy

In a virtual ‘fireside chat’, New York Fed President John Williams and ECB Chief Economist Philip Lane focused on the new frameworks for monetary policy recently carried out at their respective institutions. In her role as moderator, CEPR President Beatrice Weder di Mauro asked the speakers why they thought new strategic approaches to monetary policymaking were warranted, what were the similarities and the differences between the Fed and the ECB frameworks, and whether the economic diagnoses underlying these developments remained valid.

In his answer, Lane recognised the existence of differences among the monetary frameworks in the two areas, but – he argued – they did not reflect differences in policymakers’ preferences. Rather, they were prompted by deep-rooted asymmetries in macroeconomic conditions between the US and the euro area. As an example, Lane mentioned large chronic current account surpluses in Europe versus deficits in the US, as having implications for inflationary pressures. In the words of Lane, the euro area faced more downward pressures on inflation than the US in the pre-pandemic era. To directly address these issues, the new ECB framework emphasises that inflation must be projected to remain at 2% over the forecasting horizon, not just in the near term. He noted, however, the pandemic experience had introduced new challenges related to supply bottlenecks and cost-push shocks that altered inflation dynamics.

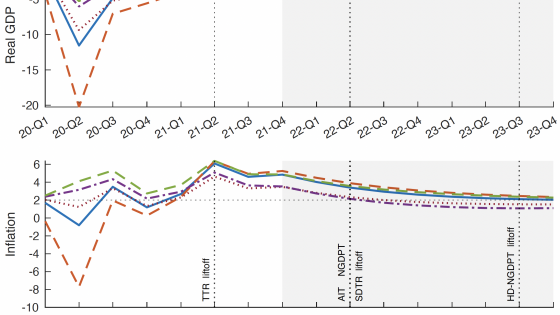

Williams pointed out that a specific asymmetry between Fed and ECB frameworks was related to the dual mandate of price stability and maximum employment for the US central bank, hence the need for the US framework to address both goals equally. Depending on the specific nature of the demand versus supply shocks hitting the macroeconomy, these goals may be in conflict over the short run, and appropriate policy needs to restore the desired outcomes accounting for the persistence and the size of the shocks. Before the pandemic, slow-moving demographic and structural factors had contributed to a low natural interest rate environment, which constrained the effectiveness of monetary policy as a tool to guarantee maximum employment and contributed to low levels of realised inflation, with potentially adverse implications on the stability of inflation expectations. An evolution of the US strategy was warranted, said Williams, and in the new framework that was characterised in terms of achieving an average inflation level of 2% while focusing on shortfalls of employment from its maximum level.

Weder di Mauro asked both speakers to appraise how the new monetary policy frameworks, which originated during periods of inflation undershooting, were able to address the specific challenges of the current high inflation leading to sizeable overshooting from central bank objectives. In particular, she asked what was their confidence that markets were understanding the new strategies. The key question was how quickly the cost-push shocks in the energy sector and the COVID-related imbalances would resolve over time. Williams emphasised that the slow-moving factors underlying a low r* environment had not likely changed during the pandemic, hence the new policy framework remained relevant. The new framework was well suited to deal not only with periods of low inflation and demand imbalances but also with price spikes reflecting supply and cost-push shocks.

Commissioner Paolo Gentiloni’s Keynote Address: “From rebound to rebuild: Three priorities for the post-pandemic economy”

In his keynote address, Commissioner Gentiloni, after reviewing the unprecedented policy response provided on both sides of the Atlantic to support the economy, indicated the three main policy priorities for the post pandemic economy: (i) deliver on what was agreed; (ii) avoid the mistakes of the past; and (iii) write a new story together.

On delivering on what was agreed, Commissioner Gentiloni stressed the importance for the EU of making a success of Next Generation EU, in particular by using effectively the funds disbursed by its core instrument, the Recovery and Resilience Facility, and ensuring that member states would keep their commitments with regard to economic reforms. On its side, the US should implement the bipartisan agreement on infrastructure that will modernise its transport and communication systems as well as help address climate change challenges. Commissioner Gentiloni also stressed the importance, both in the EU and the US, of putting in place without delay the legislation that would enable the international agreement on taxation, which represented a ‘triumph for multilateralism’.

On avoiding the mistakes of the past, Commissioner Gentiloni pointed out that governments should not move too abruptly from a supportive policy stance to a restrictive one. Public investment should not bear the brunt of fiscal consolidation, while the reduction of public debt should not come at the expense of the recovery or of investments needed for the green and digital transition.

Finally, on writing a new story together, Commissioner Gentiloni argued that, as the EU and the US share the same vision of the recovery aimed at reducing inequalities and addressing the looming climate crisis, they should work together to put in place a ‘new era of strong and sustainable growth’. In this context the word ‘sustainable’ covered three dimensions: (1) ensure debt sustainability in the medium-term while promoting a more growth-friendly composition of public finances; (2) implement the ambitious climate change commitments by translating them in concrete actions; and (3) strengthen the respective social models to make them fit for the future.