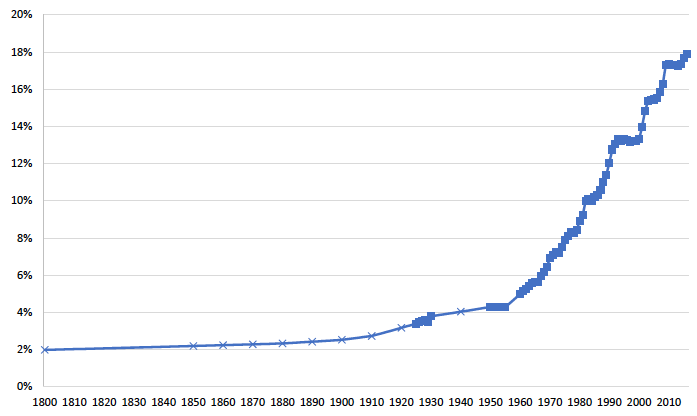

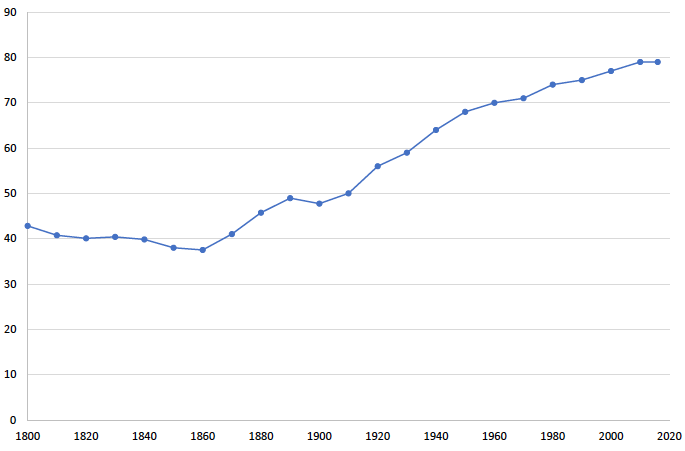

Medical care was not always an economic behemoth. It was only in the last century that medical care’s share of total employment increased tenfold (Figure 1). Before then, health was markedly poorer. Life expectancy of an average baby born in 1900 was three decades less than in 2015 (Figure 2). To what extent is the rise of medical care the source of improved health?

Figure 1 Medical spending as a share of GDP, 1800-2016

Notes: Data sources are described in the text. □ indicates actual data on medical spending as a share of GDP. x indicates extrapolation from Census employment data.

Reviewing the evolution of medical knowledge and organisations in England in the 18th century – including surgery, midwifery, medicines, hospitals, dispensaries, and preventive therapies – Thomas McKeown concluded that medical care did not contribute to the reduction in mortality in the late 18th and 19th centuries. Instead, he argued that the decline in mortality was explained by environmental change (McKeown 1955) and that even during the 20th century, medical measures played a minor role compared to improved nutrition and better hygiene (McKeown 1975). Nobel prize-winning economist Robert Fogel further argued that long-term changes in life expectancy were primarily due to increased productivity, especially in agriculture (Fogel 2004). Demographer Samuel Preston attributed longer life to advances in public health, such as clean water and sanitation (Preston 1996).

A closer look, however, reveals a more complex situation. When we traced the development of medical care and the extension of longevity in the US from 1800 onward (Catillon et al. 2018) to provide a long-term look at health and health care in the US, we found both similarities to past studies and major differences.

Figure 2 Life expectancy at birth in the US, 1800-2016

Source: Hacker, based on Fogel and Haines

Little medical care, short lives (1800-1880)

From 1800 until about 1880, medical care was small and stagnant, and health improved little. Average life expectancy in the US was 43 years in 1800 and 46 in 1880 (Hacker 2010). While understanding of disease, physiology, and anatomy improved during the 18th and 19th centuries, progress in medical knowledge did not rapidly translate into medical interventions helpful to patients (McKeown 1955). Infectious disease was the main cause of death. Sick people were safer at home than in the hospital. Health expenditures remained limited to about 2% of GDP, growing by only about 0.2% annually, even as income was rising (Catillon et al. 2018).

Then, at the end of this period, medical science paved the way for the development of public health interventions that bestowed prestige and authority to the medical profession, even before therapeutic care was able to treat individual illnesses effectively (Starr 1977).

The start of medical care growth (1880-1935)

During the period 1880-1935, scientific advances led to the regulation of the medical profession, the specialisation of doctors, and the rise of ancillary occupations. Medical spending started to accelerate, reaching robust growth of +1% above GDP by 1910 (Lough 1935, Getzen 2017). Public health improvements explained the bulk of life-expectancy gains over this period (Cutler and Miller 2005, Alsan and Goldin 2018). Reduced mortality from infectious diseases, mostly benefiting younger population groups, was concurrent with large-scale public health improvements, especially clean water and sanitation.

We asked whether the growth in medical care explained some of the life-expectancy gains realised over this time period using data from big US cities and all cities and towns in Massachusetts (Catillon et al. 2018). In 13 large US cities, filtering the water reduced mortality, but having more medical care supply did not.

We turned to Massachusetts with its early, more complete data to examine whether medical care supply explains different mortality trends across large metropolitan areas, other urban areas, and rural areas. We confirmed the effect of public health interventions (including water and sewer systems) on mortality but failed to find that medical care supply had any large impact in the pre-antibiotic era.

The antibiotic revolution (1935-1960)

The period 1935-1960 involved continued public health innovation, as well as the first widespread medical-care interventions to treat infectious diseases: sulfa drugs in the late 1930s and penicillin in the mid-1940s. Scholars estimating the effect of these medical-care interventions on the decline in mortality concluded that sulfa drugs accounted for 10-20% of the 16% decline in mortality between 1937 and 1945 (Thomasson and Treber 2008, Jayachandran et al. 2010). Some studies also found an important effect of the introduction of penicillin on mortality (Hager 2007), but others did not, suggesting that other trends might also help explain the reduction in mortality over this period (Hemminki and Paakkulainen 1976).

Between 1935 and 1960, life expectancy at birth increased from 60 to 70 years, but medical expenditures as a share of GDP only increased from 3% to 4%, and medical care as a share of total employment only increased from 2% to 3%. Better health was quite a bargain. Indeed, the bulk of life-expectancy gains over the past two centuries occurred before the era of big medicine, at a time when relatively little was spent on medical care.

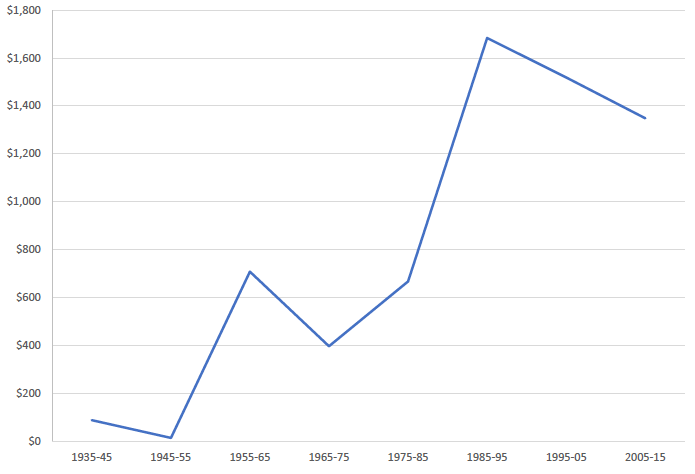

The era of big medicine (1960-2015)

Between 1960 and 2015, the cost per year of life added increased every decade. Medical spending exploded from 5% of GDP in 1960 to 18% in 2016. During this period, the decline in mortality was from a decrease in heart disease, and to a lesser extent cerebrovascular disease (stroke) and cancer, and was more pronounced at older ages, consistent with the expansion of medical knowledge and technology. Previous research showed that improved health over this period was a response to the availability of treatments, as opposed to people being better insured (Finkelstein and McKnight 2008).

We considered whether the differential decline in mortality in the Boston Statistical Metropolitan Area was the result of a greater number of physicians in the area. We found that medical care supply had no effect on mortality in 1960-1990, but had a significant effect on mortality in 1990-2015, with the largest effects for influenza/pneumonia and cancer.

The slowdown (1990-2015)

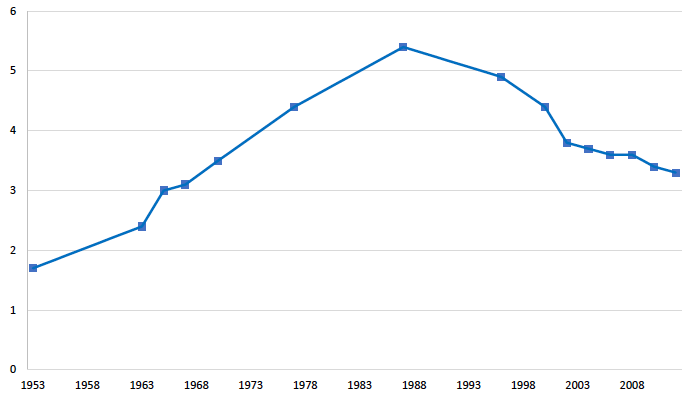

The ratio of medical spending for the elderly (people aged 65 and above) to adults (under the age of 65) grew from 1953 to 1988 and decreased from 1988 to 2012 (Figure 3). The relative increase in medical spending for the elderly through the 1980s was consistent with changes in medical knowledge, technology, and policy (including Medicare and other reimbursement rules).

Figure 3 Ratio of medical spending for the elderly to adults, 1953-2012

Note: Data for 1953 are from Cutler and Meara (1997). Data for 1963-2000 are from Meara, White, and Cutler (2004). Data for 2002-2012 are from CMS (2017).

Researchers agree that there is a recent slowdown in national health expenditures across all age groups (Figure 4), but there is little agreement on exactly why and when it started. Cutler and Sahni (2013) considered the role of the recession and estimated that it accounted for 37% of the slowdown between 2007 and 2012. They noted that a decline in private insurance coverage and cuts to some Medicare payment rates accounted for another 8% of the slowdown, leaving 55% of the spending slowdown unexplained. Researchers who asked whether the Affordable Care Act could explain part of the slowdown reached mixed conclusions about the importance of its contribution (McWilliams et al. 2013, Song et al. 2012, Colla et al. 2012).

Whatever the case may be, the slowdown began in the early 2000s, prior to the implementation of the Affordable Care Act. Chandra et al. (2013) argued that the three main causes for the slowdown were the rise in high-deductible insurance plans, state-level efforts to control Medicaid costs, and a general slowdown in the diffusion of new technology, particularly for use by the Medicare population.

The diffusion of technologies previously used among the elderly to the non-elderly population (e.g. elective hip or knee replacement for people with severe arthritis) might explain some of the relative change but is not the full story. The recent reduction in the relative growth of medical spending on people over 65 and the slowdown in the real growth rate of spending for all citizens remain to be fully understood.

Figure 4 Increase in medical spending per year of life added, by decade

Implications and lessons for policy

The contribution of medical care to life-expectancy gains changed over time. Our analysis suggests that the supply side (the growth of the medical system), not the demand side (driven by the effect of medical interventions), explains why medicine accounts for more of the economy today than in the past.

The productivity of medical spending seems to be falling, but stabilisation over the past two decades of the increase in medical spending per year of added life suggests that the continued explosion in cost is not inevitable. Current technological changes (including genetics and personalised medicine) and systemic reforms (including how medical care is paid for) might have the potential to increase the value of medical care delivered and continue recent positive trends in the value of medical care.

References

Alsan, M, and C Goldin (2018), “Watersheds in child mortality: The role of effective water and sewerage infrastructure, 1880 to 1920”, NBER Working Paper 21263.

Catillon, M, D Cutler and T Getzen (2018), “Two hundred years of health and medical care: The importance of medical care for life expectancy gains”, NBER Working Paper w25330.

Chandra, A, J Holmes and J Skinner (2013), “Is this time different? The slowdown in health care spending”, Brookings Papers on Economic Activity 288.

Colla, C H, D E Wennberg, E Meara, J S Skinner, D Gottlieb, V A Lewis, C M Snyder and E S Fisher (2012), “Spending differences associated with the Medicare physician group practice demonstration”, JAMA 308(10): 1015-1023.

Cutler, D, A Deaton and A Lleras-Muney (2006), “The determinants of mortality”, Journal of Economic Perspectives 20(3): 97-120.

Cutler, D, and G Miller (2005), “The role of public health improvements in health advances: The twentieth-century United States”, Demography 42(1): 1-22.

Cutler, D M, and N R Sahni (2013). If slow rate of health care spending growth persists, projections may be off by $770 billion”, Health Affairs 32(5): 841-850.0

Deaton, A (2004), “Health in an age of globalization”, Brookings Trade Forum 2004, Washington, D.C.: Brookings Institution Press.

Finkelstein, A, and R McKnight (2008), “What did Medicare do? The initial impact of Medicare on mortality and out of pocket medical spending”, Journal of Public Economics 92(7): 1644-1668.

Fogel, R W (2004), The escape from hunger and premature death, 1700-2100: Europe, America, and the Third World, Cambridge UK: Cambridge University Press.

Getzen, T E (2017), “The growth of health spending in the USA: 1776 to 2026”, Society of Actuaries (also forthcoming in Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Economics and Finance).

McKeown, T, and RG Brown (1955), “Medical evidence related to English population changes in the eighteenth century”, Population Studies 9(2): 119-141.

McKeown, T, R G Record and RD Turner (1975), “An interpretation of the decline of mortality in England and Wales during the twentieth century”, Population Studies 29(3): 391-422.

McWilliams, J M, B E Landon and M E Chernew (2013), “Changes in health care spending and quality for Medicare beneficiaries associated with a commercial ACO contract”, JAMA 310(8): 829-836.

Preston, S (1996), “American longevity: Past, present and future”, Policy Brief, Maxwell School of Citizenship and Public Affairs, Center for Policy Research.

Rothstein, WG (1992), American physicians in the nineteenth century: From sects to science, Baltimore: JHU Press.

Song, Z, D G Safran, B E Landon, M B Landrum, Y He, R E Mechanic, M P Day and M E Chernew (2012), “The ‘Alternative Quality Contract,’ based on a global budget, lowered medical spending and improved quality”, Health Affairs 31(8): 1885-1894.

Starr, P (1977), “Medicine, economy and society in nineteenth-century America”, Journal of Social History 10(4): 588-607.