Standing at the frontier of knowledge, the university-based workforce can play several important roles in society and the economy. University workers not only contribute through research and teaching activities, but may also start successful high-technology companies (e.g. Google and Genentech) and create valuable intellectual property (e.g. the Hepatitis B vaccine and the pain medication Lyrica). Moreover, universities can be important foundations for local innovation clusters such as Silicon Valley (Bresnahan et al. 2001).

Several European countries, observing the growth in university patenting in the US in the last several decades (Mowery et al. 2001), enacted legislation in the early 2000s seeking to emulate the US system (Lissoni et al. 2008). Prior to the reform, a university researcher retained blanket rights to his or her inventions, the so-called ‘professor’s privilege’, while post-reform the university typically got two-thirds of the income rights – a system similar to what often prevails in the US and many other countries (Lissoni et al. 2008).

Impact of the new patent reform: Evidence from Norway

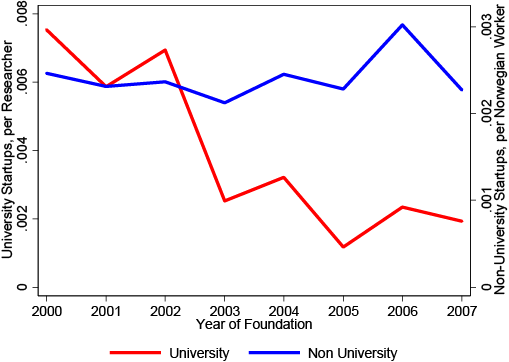

In a recent working paper (Hvide and Jones 2016), we use comprehensive data about workers, businesses, and patents, to analyse the impact of the reform in Norway. Figure 1 plots the difference in per capita startup rates for university researchers and non-university employees, for three years prior to the reform – enacted 1 January 2003 – and five years post-reform.

Figure 1. Per capita startup rates for university and non-university employees, 2000-2007

- Figure 1 shows that, post-reform, university researcher startup activity dropped by about 50%.

By comparison, as can also be seen in Figure 1, the background rate of startups in Norway as a whole did not change. The sharp relative decline among university researchers is similarly found when they are compared against individuals with increasingly similar sociodemographic characteristics (e.g. individuals with a PhD). The results for patenting activity are similar, suggesting an approximate 50% decline in patents per university researcher compared to the patenting rate among non-university inventors.

One explanation for the decline might be a lack of experience among universities; newly instituted technology transfer offices (TTOs) at the universities may have been initially unskilled at commercialisation and needed time to improve. However, even four years after the reform, there seems to be no sign of improvement; the negative effect of the reform appears to continue, as illustrated Figure 1. In the patenting analysis, we can follow university researchers until seven years post-reform and the same picture emerges; there is no bounce-back and, if anything, commercialisation rates appear to decline with additional time.

Another explanation for our findings could be that the reform eliminated the less-promising startups and patents, so that although the quantity of university-based innovation went down post-reform, the quality went up.

- The data, however, suggest that the quality also declined.

After the reform, startups by university researchers become less likely to survive and grow more slowly. Meanwhile, university-based patents receive fewer citations. Thus, not only does the quantity of commercialisations by university researchers decline, but there are declines in several quality measures as well.

The problem of university research incentives

A theoretical perspective that may explain the findings emphasises the problem of university researcher incentives, and how these can be balanced with any rights given to the university itself. How to balance ownership rights between investing parties is a classic question in economics and also provides canonical perspectives in studies of innovation (Holmstrom 1982, Grossman and Hart 1986, Aghion and Tirole 1994, Green and Scotchmer 1995). The ‘professor’s privilege’ reform is a large shock to the rights regime. Recognising the potential importance of investments by both the university researcher and the university itself, one can motivate a royalty sharing regime that favours balancing rights across parties rather than giving all royalties to one party, as under the professor’s privilege. The basic presumption here is that university-level investments are important and cannot be easily replicated by the university researcher. However, under circumstances where the university-level investments are much less important than researcher-level investments, royalty shares would be optimally balanced toward the university researcher.

Conclusion

Our stark empirical findings appear to be in sharp contrast to the motivations behind the Norwegian policy reform. The findings may also raise questions about similar reforms in other European countries that eliminated the ‘professor’s privilege’. Were the Norwegian results representative, one would imagine that the quantity of startups and patenting by university researchers would rise substantially, as would the quality, should universities give the researchers full rights. Since the post-reform regime looks like the US regime, among others, the interest in the external validity of these findings may also extend to countries outside Europe.

References

Association of University Technology Managers (2014), “Highlights of AUTM’s U.S. Licensing Activity Survey FY2014,” accessed: January 2016.

Bresnahan, T, A Gabardella, and A L Saxenian (2001), “Old Economy Inputs for New Economy Outcomes: Cluster formation in the New Silicon Valleys,” Industrial and Corporate Change, 10 (4), 835-860.

Green, J R and S Scotchmer (1995), “On the Division of Profit in Sequential Innovation,” RAND Journal of Economics, 26(1), 20-33.

Grossman, S and O Hart (1986), “The Costs and Benefits of Ownership: A Theory of Lateral and Vertical Integration', Journal of Political Economy, 94, 691-719.

Hellmann, T (2007), “When Do Employees Become Entrepreneurs?” Management Science, 53(6), 919-933.

Holmstrom, B (1982), “Moral Hazard in Teams,” Bell Journal of Economics, 13(2), 324-340.

Hvide, H K and B Jones (2016), “University Innovation and the Professor’s Privilege,” CEPR DP11139.

Kenney, M and D Patton (2009), “Reconsidering the Bayh-Dole Act and the Current University Invention Ownership Model,” Research Policy, 38, 1407-1422.

Lissoni, F, P Llerena, M McKelvey and B Sanditov (2008), “Academic Patenting in Europe: New Evidence from the KEINS Database,” Research Evaluation, 17(2), 87-102.

Litan, R, L Mitchell, and E J Reedy (2007), “The University as Innovator: Bumps in the Road,” Issues in Science and Technology, 23, 57-66.

Mowery, D, and B Sampat (2005), “The Bayh-Dole Act of 1980 and University-Industry Technology Transfer: A Model for Other OECD Governments?” Journal of Technology Transfer, 30, 115–127.