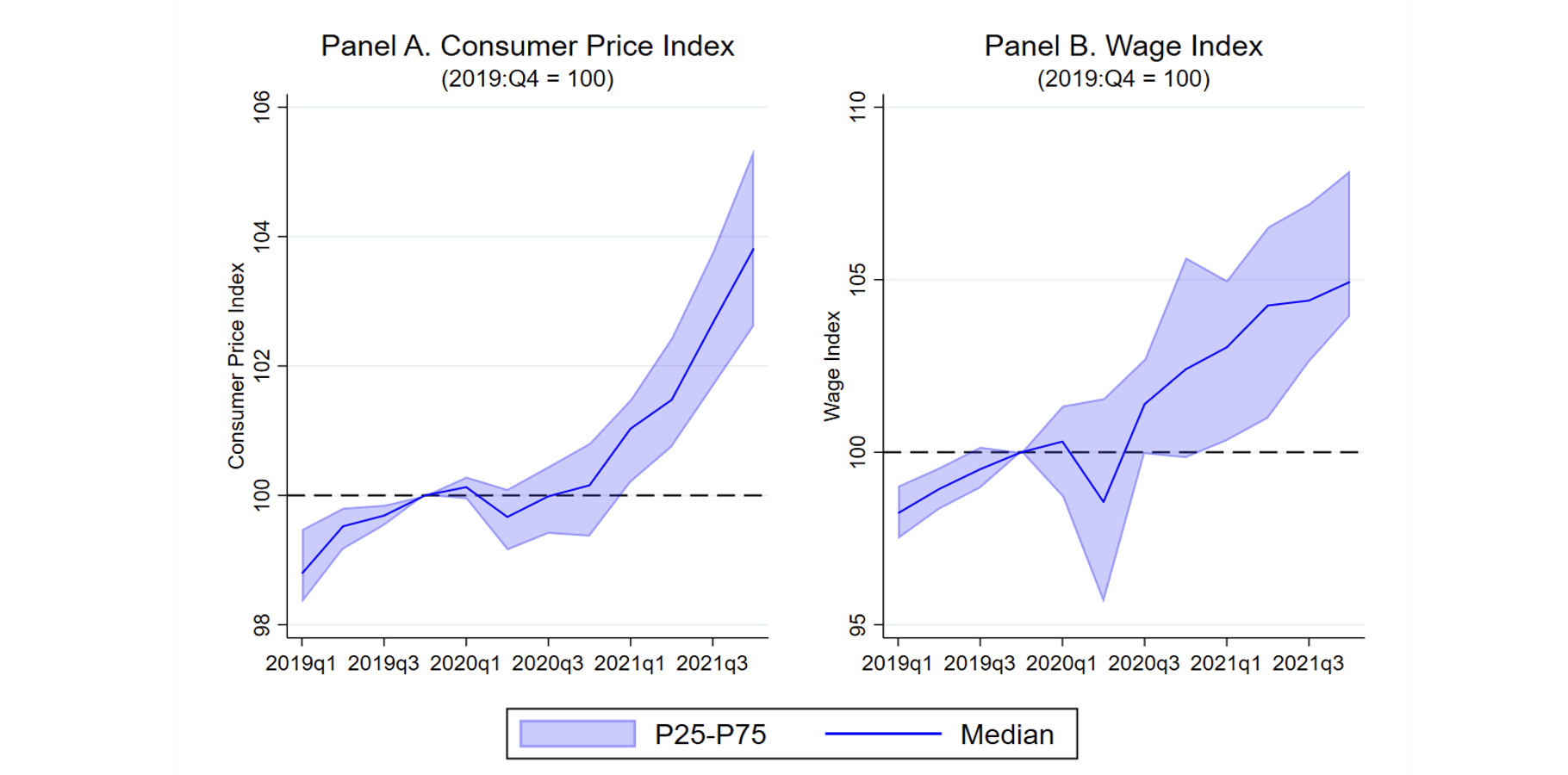

With the recovery picking up steam after the acute COVID-19 shock, inflation in 2021 rose to levels that had not been seen in almost 40 years in many economies (Figure 1, panel A). At the same time, the economic recovery has brought a resurgence in demand for labour in many sectors. Labour supply was slow to respond, with some workers hesitant to re-engage because of ongoing health concerns and difficulties finding child and family care, among other factors. This demand-supply imbalance led to tighter labour markets and increased wage pressures, with average nominal wages (per worker) rising and the unemployment rate falling across economy groups (Figure 1, panel B).

Figure 1 Recent behaviour of price and nominal wage indices, advanced economies

Sources: Haver Analytics; International Labour Organization; Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development; IMF WEO Database; and IMF Staff Calculations.

Note: Chart shows the cross-economy median and interquartile range of the consumer prices and nominal wage index. Indices are normalized so that 2019:Q4 = 100. See Alvarez et al. (2022) for details on the sample.

These recent developments have led some observers to worry about second-round effects from inflation through wages (Baba and Lee 2022a, 2022b) and a potential wage-price spiral. Blanchard (2022) notes that rising inflation and tight labour markets could prompt workers to demand nominal wage increases that catch-up to or even exceed inflation. Domash and Summers (2022) have also alerted that vacancy and quit rates in the US have substantial predictive power for wage inflation. This suggests that current labour market tightness is likely to significantly contribute to inflationary pressures in the years to come, a link that might be stronger if inflation expectations were to become de-anchored (Bobeica et al. 2020 2021, 2022). Altogether, these arguments force us to contend with the possibility that wage and price inflation could start feeding on each other and create a spiral, where both wages and prices accelerate over several quarters. But how often have such situations occurred in the past, and what has happened in the aftermath of such episodes?

Wage-price spirals are usually short-lived

We address these questions in our recent working paper (Alvarez et al. 2022) by creating a cross-economy database of past episodes among advanced economies going back to the 1960s. Unfortunately, a precise definition of wage-price spirals is lacking in the literature. Blanchard (1986) is perhaps the most known treatment of such phenomenon, where he defines the wage-price spiral as the consequence of the following mechanisms: (1) workers wish to preserve or increase real wages; (2) firms wish to preserve or increase markups over their costs (wages); and (3) nominal wages and prices take time to adjust. Thus, an inflationary shock takes time to dissipate, as workers and firms bargain over wages and prices in rounds. In contrast, the current discussion (Blanchard 2022, Boissay et al. 2022) seems to focus on the possibility that higher wage inflation constitutes a new cost-push shock to firms and therefore inflation could accelerate in the near future. This is the interpretation we adopt as well.

Specifically, we define a wage-price spiral as an episode where at least three out of four successive quarters saw accelerating consumer prices and nominal wages. Using this definition on our dataset, we identify 79 such episodes.

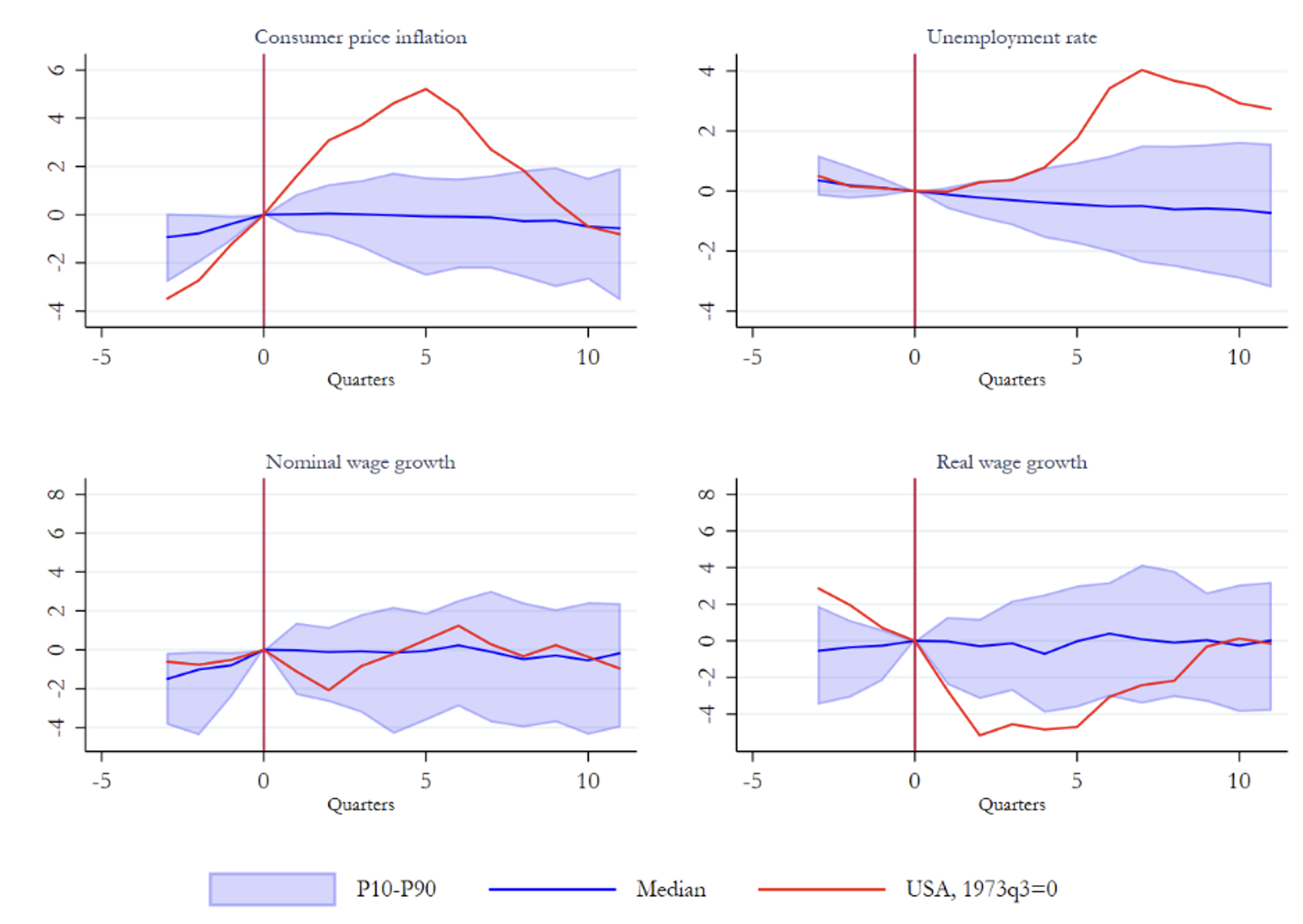

Figure 2 shows the distribution of macroeconomic outcomes around these episodes. Both consumer price inflation and nominal wage growth increases for all episodes before period 0 (the first period where the criteria that define a wage-price spiral are met), which is not surprising given how the episodes are selected. Perhaps more surprisingly is that initial dynamics, on average, are not followed by further sustained acceleration in wages and prices. In fact, inflation and nominal wage growth on average tended to stabilize in the quarters following the wage-price spiral, leaving real wage growth broadly unchanged.

Figure 2 Changes in macroeconomic variables after past episodes with accelerating prices and wages (percentage points)

Sources: International Labour Organization; Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development; US Bureau of Economic Analysis; and IMF Staff Calculations.

Note: The chart shows the developments following episodes where at least three out of four last quarters had accelerating prices and accelerating nominal wages. Quarter 0 is the first period where the criteria defining a wage-price spiral hold. See Alvarez et al. (2022) for further details.

Wage-price spirals, defined as a persistent acceleration of prices and wages, are thus hard to find in the recent historical record. In fact, only a minority of the 79 episodes identified using the criteria above saw further acceleration after eight quarters. However, in some cases inflation and wage growth elevated for a while before coming back down. Moreover, some episodes were followed by more extreme outcomes. For example, the 1973:Q3 episode for the US – spurred by the first OPEC oil embargo of the 1970s – saw price inflation surging for five additional quarters before it started to come down in 1975 (Figure 2, red lines). However, nominal wage growth did not increase, leading real wage growth to decline.

Wage growth is consistent with price and unemployment dynamics

A natural question when examining wage-price dynamics in the episodes described is to what extent they broke away from expected relationships that characterise economies in equilibrium. We explore this question using a wage Phillips curve framework, which relates wage dynamics to inflation, labour market slack, and trend productivity growth.

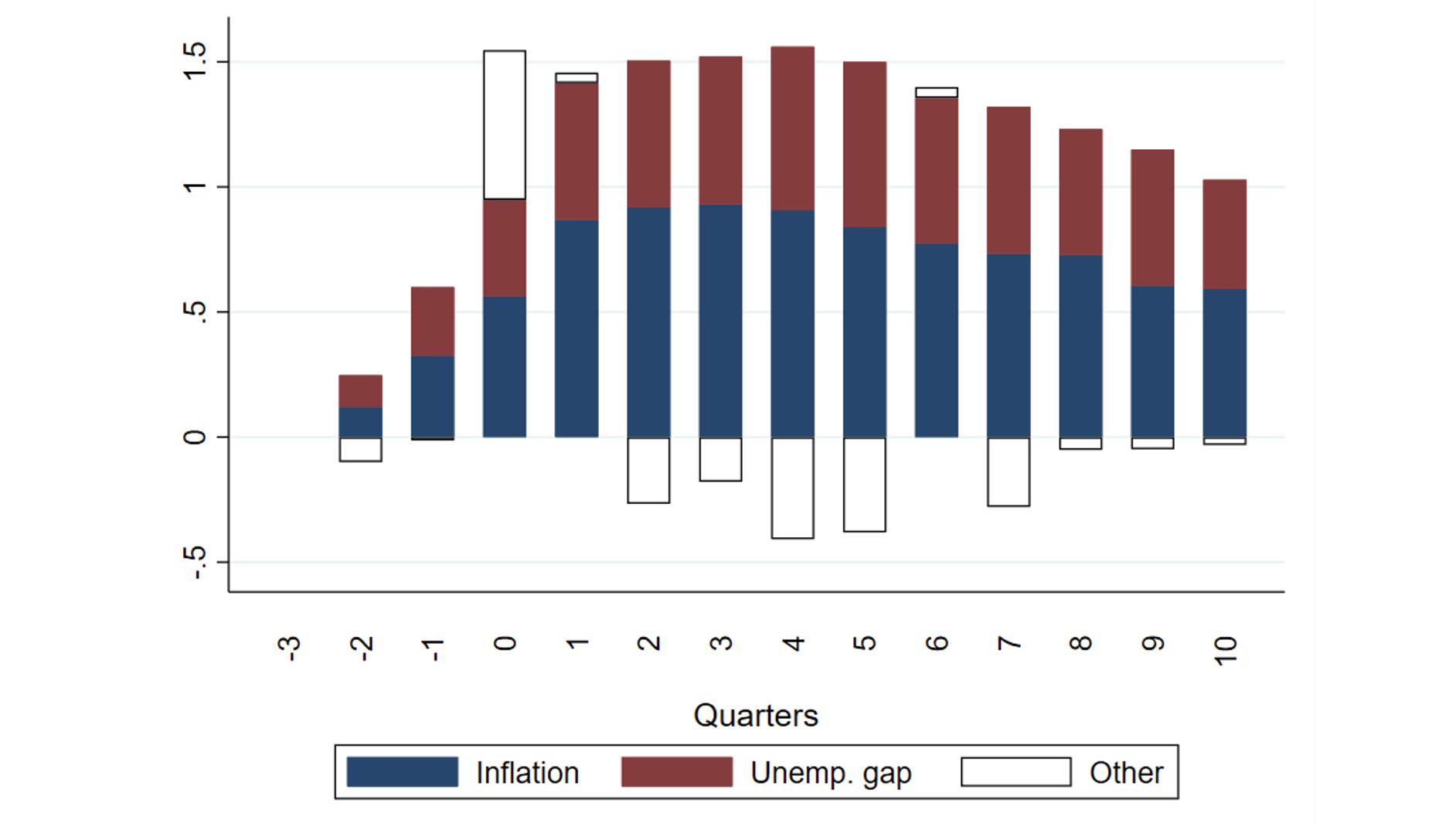

Figure 3 shows the resulting decomposition of wage growth changes (relative to the start of the identified episodes) into the inflation and unemployment gap components. The decomposition indicates that wage growth increases are driven by both inflation and labour market tightness, with either component increasing and then stabilising at a level above the start of the episode. In contrast, the behaviour of the other components is different, as they increase rapidly during the start of the wage-price acceleration episode but subside thereafter. On average, there is no persistent wage growth observed above that expected from higher persistent inflation and tighter labour markets in the episodes described.

Figure 3 Average decomposition of wage growth across episodes with accelerating prices and wages

Sources: Authors’ calculations.

Notes: ‘Other’ includes the contributions from short-term changes in unemployment gap, productivity growth, time effects and the residual. Horizontal access defined as in section 3, where zero is the first quarter where the selection criteria holds. See Alvarez et al. (2022) for further details.

Episodes similar to today did not tend to be followed by sustained wage-price spirals

An important question in the current juncture is whether advanced economies are on the verge of entering a wage-price spiral. We shed light on this question by focusing on a subset of historical episodes that are aligned with the macroeconomic dynamics recently observed, and then analyse how these episodes proceeded to unfold.

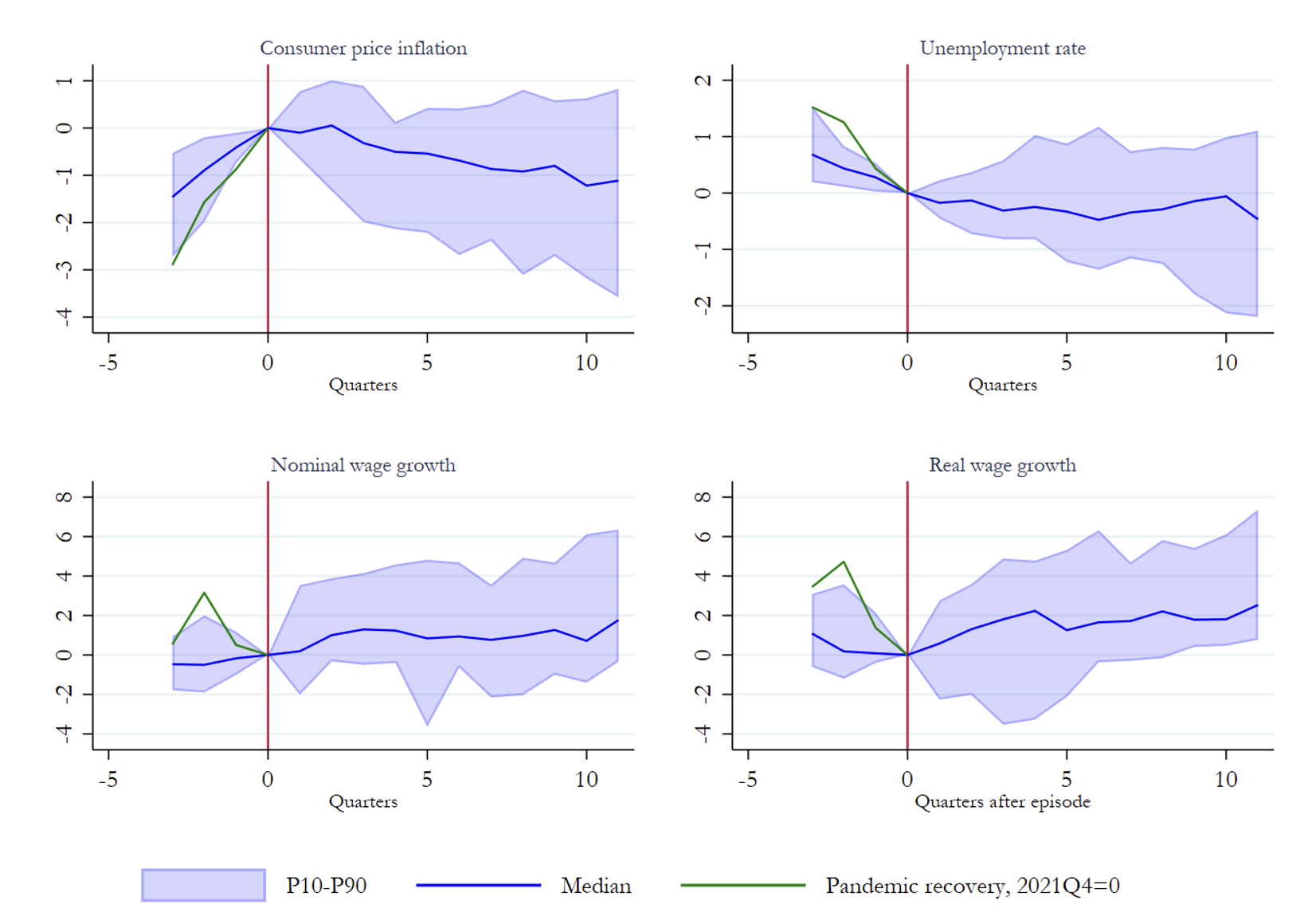

A notable feature of the most recent wage-price rise in some economies is that real wages have dropped while labour markets have tightened. We therefore identified a subset of the episodes where at least three out of four consecutive quarters are characterized by (1) increasing year-on-year inflation, (2) positive nominal wage growth, (3) negative real wage growth, and (4) flat or falling unemployment. There are 22 past episodes in our database that mimic this pattern.

These episodes did not tend to be followed by sustained wage-price spirals. On the contrary, inflation tended to fall while nominal wage growth tended to increase. This allowed real wages to recover. Moreover, the unemployment rate tended to fall (Figure 4). Overall, these similar episodes were followed by a higher increase in wage growth than in the wider set of episodes described above, but wage growth eventually stabilised. In fact, nominal wage growth after two-years seems broadly consistent with inflation and labour tightening dynamics

Figure 4 Changes in macroeconomic variables after episodes similar to 2021 (percentage points)

Sources: International Labour Organization; Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development; US Bureau of Economic Analysis; and IMF Staff Calculations.

Note: The chart shows the developments following episodes where at least three out of four last quarters had (1) accelerating prices, (2) positive nominal wage growth, (3) falling or constant real wages, and (4) declining or flat unemployment. Quarter 0 is the first period where the criteria hold. See Alvarez et al. (2022) for further details.

Will it be different this time?

Sustained wage-price acceleration is hard to find when looking at episodes similar to today, where real wages have significantly fallen. In those cases, nominal wages tended to catch up to inflation to partially recover real wage losses, and growth rates tended to stabilise at a higher level than before the initial acceleration happened. Wage growth rates eventually became consistent with inflation and labour market tightness. This mechanism did not appear to lead to persistent acceleration dynamics that can be characterised as a wage-price spiral.

It is still too early to say whether the immediate future will replicate these patterns. However, an important takeaway from the historical analysis is that an acceleration of nominal wages should not necessarily be seen as a sign that a wage-price spiral is taking hold. Indeed, the history suggests that nominal wages can accelerate while inflation recedes from high levels. In fact, this is what tended to happen after past similar episodes.

Authors' note: The views expressed are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the views of the IMF, its Executive Board, or IMF management

References

Alvarez, J, J Bluedorn, N Hansen, Y Huang, E Pugacheva, and A Sollaci (2022), “Wage-price spirals: What is the historical evidence?” IMF Working Paper 22/221.

Baba, C and J Lee (2022a), “High inflation would amplify second-round effects but need not prolong them”, VoxEU.org, 16 September.

Baba, C and J Lee (2022b), “Second-round effects of oil price shocks—Implications for Europe’s inflation outlook”, IMF Working Paper 22/173.

Blanchard, O (1986), “The wage price spiral,” The Quarterly Journal of Economics 101(3): 543-566.

Blanchard, O (2022), “Why I worry about inflation, interest rates, and unemployment,” Realtime Economic Issues Watch, 14 March.

Bobeica, E, M Ciccarelli and I Vansteenkiste (2020), “The link between labor cost inflation and price inflation in the Euro area”, in G Castex, J Gal, and D Saravia (eds), Changing inflation dynamics, evolving monetary policy, Volume 27 of Central Banking, Analysis, and Economic Policies Book Series No 27, Central Bank of Chile.

Bobeica, E, M Ciccarelli and I Vansteenkiste (2021), “The changing link between labor cost and price inflation in the United States”, Working Paper Series 2583, European Central Bank.

Bobeica, E, M Ciccarelli and I Vansteenkiste (2022), “What we know about the wage inflationary channel”, VoxEU.org, 4 April.

Boissay, F, F De Fiore, D Igan, A Pierres-Tejada and D Rees (2002), “Are major advanced economies on the verge of a wage-price spiral?”, BIS Bulletin 53.

Domash, A and L Summers (2022), “How tight are US labor markets?”, NBER Working Paper 29739.