Sport matters. Professional sport is a big industry. In 2004, it generated value added of €407 billion, accounting for 3.7% of EU GDP (Dimitrov et al., 2006). Sports and related activities employ 15 million people, comprising 5.4% of the EU labour force. Sporting success at national level enhances citizens’ sense of life satisfaction and well-being (Dohmen et al., 2006; Szymanski and Kavetsos, forthcoming).

Not surprisingly, economists are devoting more attention to the industry. Labour economists have been attracted to professional sports for some time because worker and team performance and rewards are readily observable. Critics question the value of these studies, arguing that professional athletes are rather unusual workers with unusual attributes and unusual wages, making it difficult to extrapolate from sports studies to the general population. However, there is a long tradition of focusing on ”extremes” and unusual cases to improve our understanding of incentives. Consider the behavioural economics literature focused around criminal activity.

At present there is public concern that some workers – chiefly senior executives in ‘bailed out’ companies and banks – are reaping huge financial rewards for what appears to be very poor performance. The retort is that these highly paid senior executives are simply being paid their market worth and that attempts to pay them less could lead to lack of motivation of effort and increased likelihood of the best executives quitting for better opportunities elsewhere.

The debate is familiar to those with knowledge of sports economics. Some professional sports in the US, notably American football and ice hockey, have team payrolls that are heavily regulated in a salary cap arrangement. As yet it is not wholly clear what the impact of these rules and regulations is on incentives, individual performance, and team performance.

In Europe, where there is a long tradition of not interfering in professional athletes’ wages, earnings can be very substantial. Professional football players in particular earn considerable amounts of money. This comes in the form of endorsements and sponsorship, but also from their wages as football players. If you ask supporters whether the players in their team deserve what they earn, some will say nobody deserves to earn €X more than the person in the street (the argument levelled at bankers, traders and the like) but most will say: “it all depends on how they perform on the field”.

There’s the rub. How do we really know whether players receive a wage that is equivalent to their marginal productivity? We may know in considerable detail what they have been doing on the pitch – how many passes they have made, how many goals they scored, how many appearances they made – and this clearly helps. But we have more than that; a variable that really identifies a rare talent that teams are very likely to pay for. This is two-footedness.

The value of two-footedness

Two-footedness is the ability to use both feet to pass, tackle and shoot. Unsurprisingly, this versatility is strongly related to player performance. Furthermore, it is a fairly unusual talent – around one-sixth of the players in the top five European leagues are two-footed. Although it can be taught from an early age, it rarely occurs. This is changing. A football school was set up in the UK in 2004 claiming to be “the first and original soccer school that concentrates solely on improving the other foot”1. Nevertheless, this training of two-footedness is something that can only be properly developed at an early age in the formative years of a player’s career and is difficult to instil in today’s established professional players. Furthermore, a recent study of amateur and professional players found a “surprising absence of plasticity in foot use, given the importance of learning, experience, and culture in models of handedness and footedness” (Carey et al., 2009). Hence, we can treat footedness as a pre-determined specialist ability that is capable of generating a return.

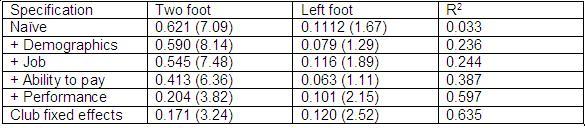

Does this talent translate into wages? The answer is “yes”. The table shows the raw premium of over 60% relative to right-footed players falls to around 40% controlling for demographic characteristics, position in the team and the team’s ability to pay players. It falls by half to around 20% when controlling for other performance measures, but remains at around 20% with all these controls. It remains large even within teams.

Table 1. Footedness effects on wages relative to right-footedness, pooled data for the top 5 European football leagues

Note: N = 1991. t statistics in parentheses are robust to heteroskedasticity. Control variables are as follows. Demographics: age, age squared, full set of nationality dummies. Job: defender, midfield, forward. Ability to pay: attendance variables by country. Performance: appearances, substitute appearances, goals per game, Champions’ League appearance dummies, international status dummies.

This is strong evidence of a clear link between performance and wages among professional football players. But is there anything in it for teams? Are they able to appropriate any of the returns to employing two-footed players? In an efficient labour market where players are free to move – as they have been since the Bosman Ruling in the European Court of Justice in 1995 – players should be able to hold onto their hard-earned cash. The empirical evidence seems to confirm this. Having controlled for other relevant factors such as total payroll, the proportion of two-footed players in a team does not significantly affect the number of points the team gets at the end of the season. It seems that two-footed players are able to appropriate the rents from their scarce talent.

The study of football – the clubs, the players, the managers, the referees – is beginning to tell us more and more about the operation of labour markets and incentives. Recent contributions have shown how rule changes intended to enhance the returns to winning, such as giving 3 points for a win instead of 2, whilst sound from a tournament theory perspective, result in sabotage behaviour (Garicano and Palacios-Huerta, 2005 and del Corral, Prieto-Rodriguez and Simmons, forthcoming); how referee bias occurs in the presence of social pressure from football fans (Buraimo, Forrest and Simmons, forthcoming); and how and when owners choose to bribe officials in order to win games (Boeri and Severgnini, 2008). There is, no doubt, more to come, though it is unlikely to silence the critics of sports economics.

Footnotes

1 Those who set up the school cite the inspiration of Tom Finney, famous English forward in the 1950s, who played in all the forward positions for England having taught himself two-footedness.

References

Boeri, T. and Severgnini, B. (2008), “The Italian job: match rigging, career concerns and media concentration in Serie A”, IZA Discussion Paper 3745, Bonn.

Buraimo, B., Forrest, D. and Simmons, R. (forthcoming), “The twelfth man?: Refereeing bias in English and German soccer”, Journal of the Royal Statistical Society, Series A.

Del Corral, J., Prieto-Rodriguez, J. and Simmons, R. (forthcoming), “The effect of incentives on sabotage: The case of Spanish football”, Journal of Sports Economics.

Dimitrov, D., Helmenstein, C., Kleissner, A., Moser, B. and Schindler, J. (2006) ‘The Macroeconomic Effects of Sports in Europe’, Studie im Auftrag des Bundeskanzleramts, Sektion Sport, Wien.

Dohmen, T., Falk, A., Huffman, D. and Sunde, U. (2006), “Seemingly irrelevant events affect economic perceptions and expectations: The FIFA World Cup 2006 as a natural experiment”, IZA Discussion Paper 2275, Bonn.

Garicano, L. and Palacios-Huerta, I. (2005), “Sabotage in tournaments: Making the beautiful game a bit less beautiful”. Centre for Economic Policy Research Discussion Paper No. 5231.

Szymanski, S. and Kavetsos, G. (forthcoming), “National well-being and international sports events”, Journal of Economic Psychology.