Western economies have set up a wide variety of safety net programmes to prevent people from ending up in poverty, in part by insuring various risk factors that may cause an earnings loss such as a disability or long-term illness. Participation in these programmes could be correlated across generations simply because parents and their children share common factors, like genetics and socioeconomic background, which determine the probability of becoming disabled. However, a potential risk of these benefit schemes is that they may create a culture of dependency within families. A snowball effect across generations could arise if welfare dependency is transmitted from parents to their children, with potentially serious consequences for the future economic situation of children.

Although an extensive literature has documented the fact that intergenerational correlations in welfare receipt exist, as Black and Devereux (2011) point out, there is little evidence on whether this relationship is causal. Testing for the existence of a behavioural response, where children become benefit recipients becausetheir parents were, is difficult for two reasons: first, a parent's participation in a benefit program is not random; and second, any analysis requires a panel dataset in which parental outcomes can be linked to those of their children over a long period of time.

Our work overcomes these identification challenges by exploiting a 1993 reform in the Dutch Disability Insurance (DI) programme combined with a rich administrative dataset (Dahl and Gielen 2018). The 1993 reform tightened DI eligibility for existing and future claimants, but exempted older cohorts currently on DI (age 45+) from the new rules. This reform generates quasi-experimental variation in DI use which can be used in a regression discontinuity design. Intuitively, the idea is to compare the children of parents who are just over 45 years of age to children whose parents are just under 45. Both sets of children and their parents should be similar on all observable and unobservable dimensions, with the only difference being parental exposure to the reform.

Intergenerational links in participation

The first step is to understand the impact of the 1993 reform on parents. Figure 1 shows that parents who were just under the age 45 cut-off, and therefore subject to the harsher DI rules, are 5.5 percentage points more likely to exit DI by the year 1999 compared to parents just over the age 45 cut-off. These treated parents saw a 1,300 euro drop in payments on average. As documented by Borghans et al. (2014), the reform changed other outcomes as well. There is a strong rebound in labour earnings and a substitution to other social assistance programs in the short run.

Figure 1 Effect of the reform on parental exit from DI

Note: The figure shows average parental exit from DI by 1999, aggregated into six-month age bins, based on the parent's age as of the reform date of August 1993. The solid trend lines are based on regressions, with dotted lines indicating pointwise 90% confidence intervals.

Source: Own calculations based on data from Statistics Netherlands.

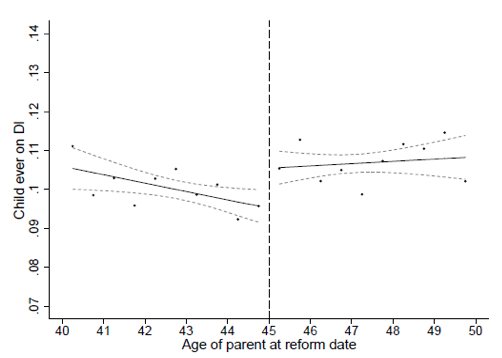

The second step is to see how children’s DI use changed based on whether the reform affected their parents. We measure a child’s cumulative use of DI as of 2014, by which time they are 37 years old on average. Figure 2 reveals a noticeable jump in child DI participation at the parental age cut-off of 45. There is an economically significant 1.1 percentage point drop for children if their parent was exposed to the reform, which translates into an 11% effect relative to the mean child participation rate of 10%. These findings complement results from Dahl et al.(2014) and Hartley et al. (2017) that welfare cultures, defined as a causal intergenerational link, exist.

Figure 2 Spillover effects on a child's DI participation

Note: The figure shows average parental exit from DI by 1999, aggregated into six month age bins, based on the parent's age as of the reform date of August 1993. The solid trend lines are based on regressions, with dotted lines indicating pointwise 90% confidence intervals.

Source: Own calculations based on data from Statistics Netherlands.

Earnings and educational spillovers

To get a fuller picture of intergenerational spillovers, we examine whether a child’s taxable earnings and participation in other social support programmes change. Cumulative earnings up to 2014 rise by approximately €7,200 euros, or a little less than 2%, for children of parents subject to the less generous DI rules. In contrast, we find no detectable change in cumulative unemployment insurance receipt, general assistance (i.e. traditional cash welfare), or other miscellaneous safety net programs.

Looking at a child’s educational attainment, there is intriguing evidence for anticipatory investments. When a parent is subject to the reform which tightened DI benefits, their child invests in 0.12 extra years of education relative to an overall mean of 11.5 years. Since most schooling takes place before children have entered the labour market, these findings provide suggestive evidence that children of treated parents plan for a future with less reliance on DI in part by investing in their labour market skills.

Fiscal consequences

These strong intergenerational links between parents and children have sizable fiscal consequences for the government’s long term budget. Cumulative DI payments to children of the targeted parents are 16% lower. This is a substantial additional saving for the government’s budget, especially since there is no evidence that children substitute these reductions in DI income for additional income from other social assistance programmes. Furthermore, there is a fiscal gain resulting from the increased taxes these children pay due to their increased labour market earnings. Overall, we calculate that through the year 2013, children account for 21% of the net fiscal savings of the 1993 Dutch reform in present discounted value terms. This share is projected to increase to 40% over time, since DI payments cease when parents reach age 65, whereas their children have on average another 30 years of work life remaining.

Possible mechanisms

What might be responsible for these sizable intergenerational links? Bertrand et al. (2000) argue that welfare spillovers within families can arise via the transmission of information, beliefs, or norms. In our study, however, it cannot be information about how to apply for the programme, as all parents have been through the same DI screening process. Similarly, reductions in stigma from observing a parent participate seems improbable, as parents have already been on DI for over 7.5 years on average prior to the reform.

Another potential explanation we can rule out is differential investments made by parents when raising their children. Parental leisure for those affected by the reform decreased and work hours increased, with total parental income changing little in the short run but declining in the long run. Since this implies less parental supervision and income, it does not align with our findings pointing to a better labour market position in later life.

Two possible mechanisms consistent with our findings are that children experience a scarring effect or learn about formal employment.

- Scarring may arise when a child observes a parent being forced off of DI or having their DI payment cut, with the child inferring that one cannot rely on the government to take care of them in the future (similar to the effect found in Malmendier and Nagel 2011).

- Learning about employment may arise if parents transmit information about the labour market or provide a positive role model due to their increased employment.

Implications for long-run policy

The finding of causal intergenerational links has several important policy lessons. Not only do programme reforms today affect the direct target population, but they can have sizable spillovers to the next generation. Apart from any equality considerations, this implies that determining the long-term fiscal impacts of government assistance programmes requires a full intergenerational accounting which includes changes in taxes paid and other transfer program receipt.

Is intergenerational dependence a good or a bad thing? That question cannot be answered without taking a stand on whether the affected children should or should not be participating in the program. In our setting, it is plausible that the reduction in DI use and increase in earnings and education was a positive benefit, both for the children and the government’s budget. But in other settings, it is important to recognise that spillovers could result in suboptimal outcomes.

References

Bertrand, M, E F P Luttmer and S Mullainathan (2000), “Network effects and welfare cultures”, The Quarterly Journal of Economics 115(3): 1019–1055.

Black, S and P Devereux (2011), “Recent developments in intergenerational mobility”, in O Ashenfelter and D Card (eds), Handbook of Labor Economics, Volume 4B, Elsevier, Chapter 16: 1487–1541.

Borghans, L, A Gielen and E Luttmer (2014), “Social support substitution and the earnings rebound: Evidence from a regression discontinuity in disability insurance reform”, American Economic Journal: Economic Policy 6(4): 34–70.

Dahl, G B and A C Gielen (2018), “Intergenerational spillovers in disability insurance”, NBER Working paper no 24296.

Dahl, G, A R Kostol and M Mogstad (2014), “Family welfare cultures”, Quarterly Journal of Economics 129(4): 1711–1752.

Hartley, R P, C Lamarche and J P Ziliak (2017), “Welfare reform and the intergenerational transmission of dependence”, IZA Discussion Papers 10942.

Malmendier, U and S Nagel (2011), “Depression babies: Do macroeconomic experiences affect risk taking?” The Quarterly Journal of Economics 126(1): 373–416.