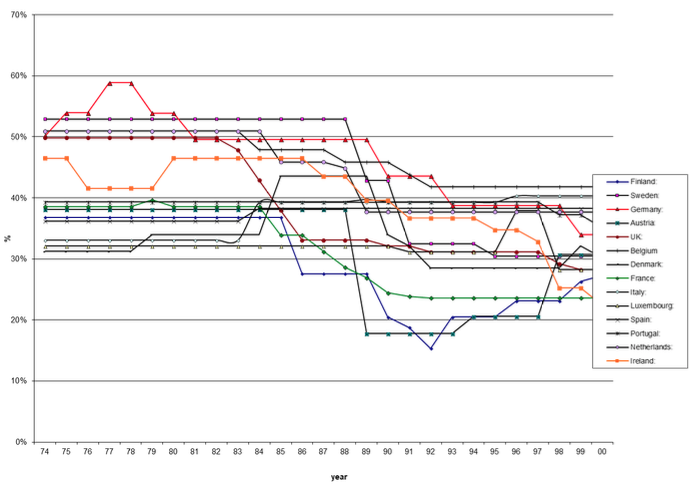

The creation of the EU provides a ‘natural experiment’ to study the effect of globalisation on business tax policies. Figure 1 demonstrates the cross-country tax convergence that took place before and after the launch of the EU.

Figure 1 Hall-Jorgenson effective tax rates on corporate income in selected EU countries1

Notes: Modelled after Hall and Jorgenson (1967). Assumptions: Equity finance, borrowing rate = 4 %, inflation rate p= 4 %, depreciation rate = 20 %, normal tax life = 10 years.

Source: Razin et al. (2005), Razin and Sadka (2018).

The effects of the establishment of the EU on social benefits and the welfare state system are particularly significant. Caminada et al. (2010) explored EU welfare-state indicators. They employed a variety of indicators of social protection – social expenditures, both at the macro and at the programme level, replacement rates of unemployment, and social assistance benefits and poverty indicators. Together, these indicators paint a relatively broad picture of the evolution of social protection in the EU. The convergence regressions that the authors employed demonstrate that the initial level of public social expenditure prior to the creation of the EU has a negative effect on the EU provision of public social services well after the EU was established.

However, as we show in a recent paper (Razin and Sadka 2018), despite the tax-competition induced fall in tax revenue and the downscaling of social benefits, the welfare state spreads the gains from trade to all income groups, so that globalisation generates a Pareto improvement.2

Political economy analytics

To put together financial globalisation, tax competition, and the welfare state redistributive system in a coherent analytical framework, and examine interactions among them, we develop a two-period, one-good, small-open-economy model. We consider first the extreme case when the welfare state does not exist. We demonstrate that in the absence of redistribution, the consequences of financial globalisation are that high-skilled individuals gain and that low-skilled individuals lose. In the presence of an endogenously determined welfare state system, financial globalisation shifts the tax burden away from the mobile factor (domestic capital) to the immobile factor (labour). However, the total tax burden becomes smaller, and consequently, the provision of social benefits per capita is reduced. Regardless of who is the deciding majority, globalisation is a Pareto-improving change.

The ageing welfare state

The welfare state needs immigration to be sustained. The political coalitions that are induced by ageing will opt for allowing in young and productive migrants that can support the welfare state (Razin et al. 2014).

West European countries are following what seems to be a normal demographic path. As they became richer after the 1950s, their fertility rates fell sharply. The average number of children borne by each woman during her lifetime fell from well above the ‘replacement rate’ of 2.1 – the rate at which the population remains stable – to less than 1.4 now. Not only are populations shrinking, but they are also ageing (Financial Times 2018).

To highlight the intrinsic dynamics of coalition formation in the context of an ageing welfare state and in the presence of migration, we analyse the political-economic equilibrium policy rules consisting of the tax rate, the skill composition of migrants, and the total number of migrants. We assume that there are three distinct voting groups: skilled workers, unskilled workers, and old retirees. The essence of inter- and intra-generational redistribution of a typical welfare system is captured with a proportional tax on labour income to finance a transfer in a balanced-budget manner. When none of these groups enjoys a majority (50% of the voters or more), political coalitions will form. With overlapping generations and a policy-determined influx of immigrants, the formation of the political coalitions changes over time. With forward-looking voters, the future changes are strategically considered when policies are shaped.

A common feature among models with Markov-perfect equilibrium, as in Razin et al.’s (2014) model, is the idea that today’s voters have the power to influence the identity of future policymakers. This work builds a dynamic political-economic model featuring three distinct voting groups: skilled workers, unskilled workers, and retirees, with both inter- and intra-generational redistribution, resembling a typical welfare state. The skilled workers are net contributors to the welfare state whereas the unskilled workers and old retirees are net beneficiaries. This model provides an analytical characterisation for the policymaking coalitions, which affect the tax rate, immigrants’ skill composition, and the total number of immigrants.

The model is designed to make a three-dimensional policy choice in such a way that there is a clear ‘left’ group, a ‘centre’ group, and a ‘right’ group. The left group consists of the old native-born and the old first-generation immigrants (both skilled and unskilled) who earn no income and wish to extend as much as possible the generosity of the welfare state. They prefer to admit as many skilled immigrants as possible to help finance the generosity of the welfare state. The right group consists of native-born skilled workers who bear the lion’s share of financing the welfare state and wish therefore to downscale its generosity as much as possible. The attitude of this group towards skilled immigrants is subject to two conflicting considerations. On the one hand, they benefit from the contribution of the skilled immigrants to the financing of the welfare state, which alleviates the burden on them. On the other hand, they are aware that the offspring of the skilled immigrants will vote to downscale the generosity of the welfare state in the next period, when the members of this right group turn older and benefit from it. The fact that the fertility rate of immigrants is larger than that of the native-born amplifies this consideration.

The centre group consists of the native-born unskilled young. They do like the generous welfare state, but not as much as the old because they also pay for it. They like it more than the native-born skilled young, because they pay less for it, making them net beneficiaries. With respect to immigration, they (like the native-born skilled young) face two conflicting effects. On the one hand, they would like to admit skilled immigrants who contribute positively towards the finances of the welfare state in the current period. But, on the other hand, they are concerned that the skilled offspring of these skilled migrants will tilt the political balance of power in favour of the skilled in the next period, which would limit the generosity of the welfare state. The centre group is more accepting of skilled immigrants than the left group, but similar in attitude to the right group.

Concluding remarks

Can the welfare state, financed by labour and capital taxes, survive international tax competition brought about by financial globalisation? Evidently, the answer is yes. The welfare state is crucial for spreading the gains from financial asset trade across various income groups. We present a political economy analysis, where the pillars of the welfare state system are determined by the majority (either the low-skilled or the high-skilled), to assess the forces of globalisation on income inequality. The welfare state allows immigration in order to sustain its financing. One would naturally expect that as population ages, the political clout of the elderly would strengthen the pro-welfare state coalition. Similarly, one would expect this coalition to gain more political power as more low-skill migrants are naturalised. Ageing tilts the political power balance in the direction of boosting the welfare state, imposing a growing burden on the existing workforce, by allowing more immigration. Ageing plausibly also tilts the political power balance in favour of a larger, capital-income financed welfare state.

References

Auerbach, A J (1983), “Corporate taxation in the United States”, Brookings Papers on Economic Activity 2: 451-513.

Caminada, K, K Goudswaard and O V Vliet (2010), “Patterns of welfare state indicators in the EU: Is there convergence?” Journal of Common Market Studies 48(3): 529-556.

Financial Times (2018), “How Japan’s ageing population in shrinking”, 16 May.

Hall, R E and D W Jorgenson (1967), “Tax policy and investment behavior”, American Economic Review 57: 391-414.

King, M A and D Fullerton (1984), “Comparisons of effective tax rates”, in King, M A and D Fullerton (eds.), The taxation of income from capital: A comparative study of the United States, the United Kingdom, Sweden, and Germany, Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Razin, A and E Sadka (2018) “The welfare state besides globalization forces”, NBER working paper 24919.

Razin, A , E Sadka and B Suwankiri (2014), Migration and the welfare State: Political-economy formation policy, Cambridge: MIT Press.

Razin, A, E Sadka and C W Nam (2005), The decline of the welfare state: Demography and globalization, Cambridge: MIT Press.

Endnotes

[1] See Auerbach (1983) and King and Fullerton (1984) for comprehensive empirical application of effective corporate taxation to data.

[2] Except for the case of unskilled labour with no access to the capital market.

[EN1]Figures 3 and 4 seem to be reproduced from FT

[EN2]There is no Razin et al. 2017 paper in the bibliography. Presume it refers to the same paper, Welfare state besides globalization forces.

[EN3]I don’t know which one of these two papers the column refers to, but it probably must refer to this one as there is already another Vox column on the ‘financial globalization and the welfare state’ paper. I therefore deleted that paper from the biblio.