Industrial policy is back on the agenda in high-income countries. Indeed, the renewed interest in industrial policy appears across the political spectrum. On 30 September 2021, the Biden administration reaffirmed that it will continue the Trump adminstration’s trade war policies with respect to China, as well as its expectation that China will abide by its agreement to buy US goods (Swanson and Bradsher 2021). The Biden administration’s plan to shore up supply chains in key industries following the pandemic shocks is also based on industrial policy-style initiatives (The White House 2021). Of course, developing countries have engaged in activist industrial policies throughout the post-war period, with China being only the most prominent and recent example (Heilmann and Shih 2013).

By contrast, mainstream growth and trade economists have for the most part been sceptical of activist industrial policy, for two mutually reinforcing reasons. First, while it is possible to write down fully articulated models in which industrial policies are welfare-improving, this is only true under the circumstances that are somewhat special, such as productivity externalities or rents. And second, the existence of those conditions is extremely difficult to establish empirically. Part of the challenge is availability of systematic data on industrial policy measures. This scarcity is compounded by the fact that assessing the long-term effects of industrial policy requires information for the more distant past, making data collection even more difficult. As a result, notwithstanding a large body of narrative accounts, credible econometric evidence on the long-term effects of industrial policies is still rare.

In a recent paper (Choi and Levchenko 2021), we use a novel dataset on firm-level industrial policy measures in South Korea in the 1970s to examine their impact on the South Korean economy. South Korea's experience with industrial policy is important to understand, as it is one of the ‘growth miracle’ economies of the post-war era, known for its rapid transformation from a commodity and light manufacturing producer to a heavy manufacturing powerhouse. It has been argued that industrial policy played a central role in this transformation. However, a more complete understanding of how and how much industrial policy contributed to South Korea's development remains elusive.1

Our focus is the Heavy and Chemical Industry (HCI) Drive between 1973 and 1979. The main industrial policy tool employed by the Korean government during the HCI Drive was the allocation of foreign credit. Under the Foreign Capital Inducement Act, the Korean government strictly regulated domestic firms' direct financial transactions with foreign firms and only selectively allowed targeted firms to borrow from abroad. Once domestic firms got the approval to borrow internationally, the Korean government guaranteed the loan, so that the targeted firms could borrow at more favourable interest rates than those prevailing domestically.2

We compile information from various sources to construct a dataset of foreign credit allocations and balance sheets at the firm level. The resulting data set is representative of the Korean economy and covers the universe of foreign credits allocated to each domestic firm. Once domestic firms got approval from the government, they had to report detailed information on the loan contracts and how they plan to use the allocated credit. The reported contract information is our main data source on subsidized credit. The information is hand-collected from the national historical archives and digitised.

Of course, allocation of subsidies is endogenous to both firm and macroeconomic conditions. Our identification strategy to establish a causal impact of subsidies on firm outcomes uses two institutional features of the HCI Drive. First, the HCI Drive was suddenly initiated in 1972 and terminated in 1979 by political shocks rather than domestic economic conditions (Lane 2019). President Nixon declared the withdrawal of the US forces from South Korea, which heavily relied on the US troops for its defence against North Korea. In response, President Park started promoting heavy and chemical industries to modernize military capabilities and become more self-reliant in national defence. The HCI Drive ended after the assassination of President Park in 1979. Second, the HCI Drive had pronounced regional variation. It targeted the southeastern part of the country and developed industrial complexes in these regions. Most of the subsidies were allocated to firms in these industrial complexes. Our research design compares the difference between firms in the HCI and non-HCI sectors in the targeted regions to the difference in the non-targeted regions.

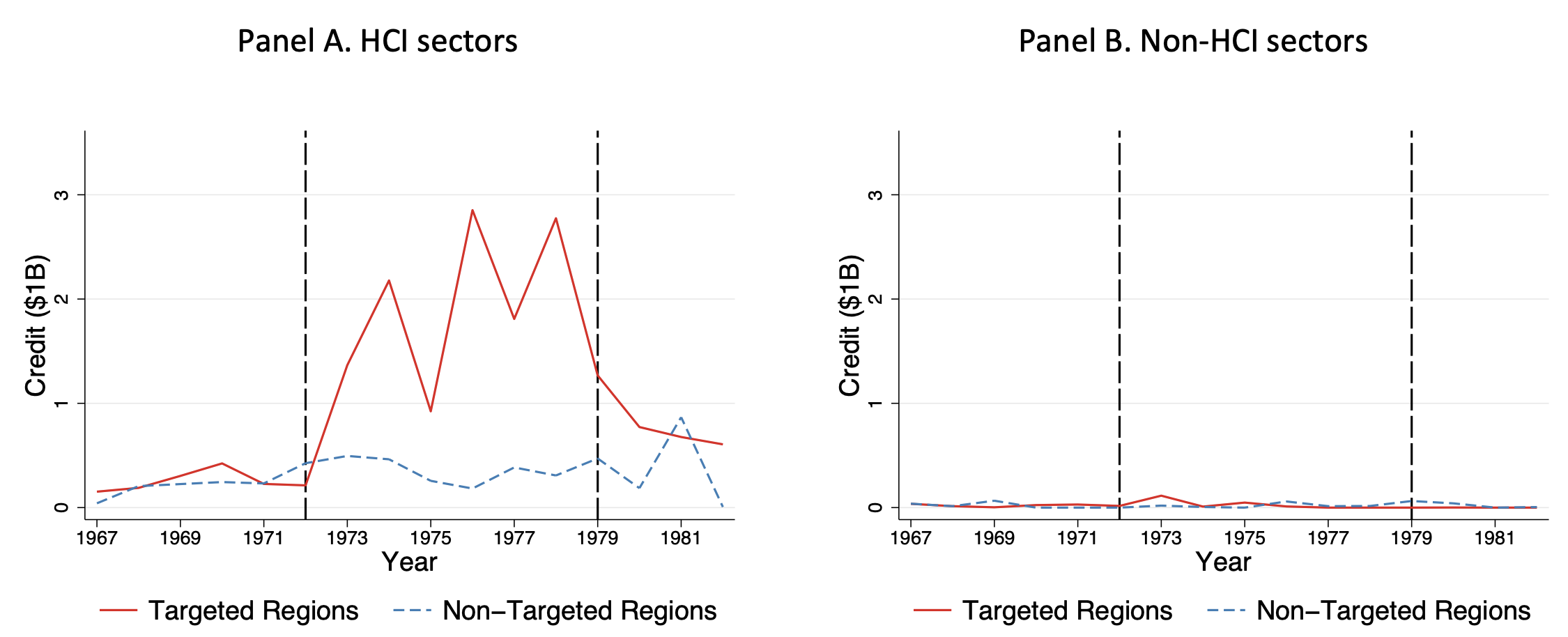

To illustrate the sources of identifying variation, Figure 1 plots the allocation of subsidized credit in HCI sectors (left panel) and non-HCI sectors (right panel), splitting by targeted and non-targeted regions. The differential treatment is evident: while there was no noticeable subsidised credit in non-HCI sectors in any region, the HCI sector credit shows a clear difference between targeted and non-targeted regions. The figure also shows the clear timing of both the onset and the termination of the subsidies, consistent with the historical narrative.

Figure 1 Foreign credit allocation by sector and region

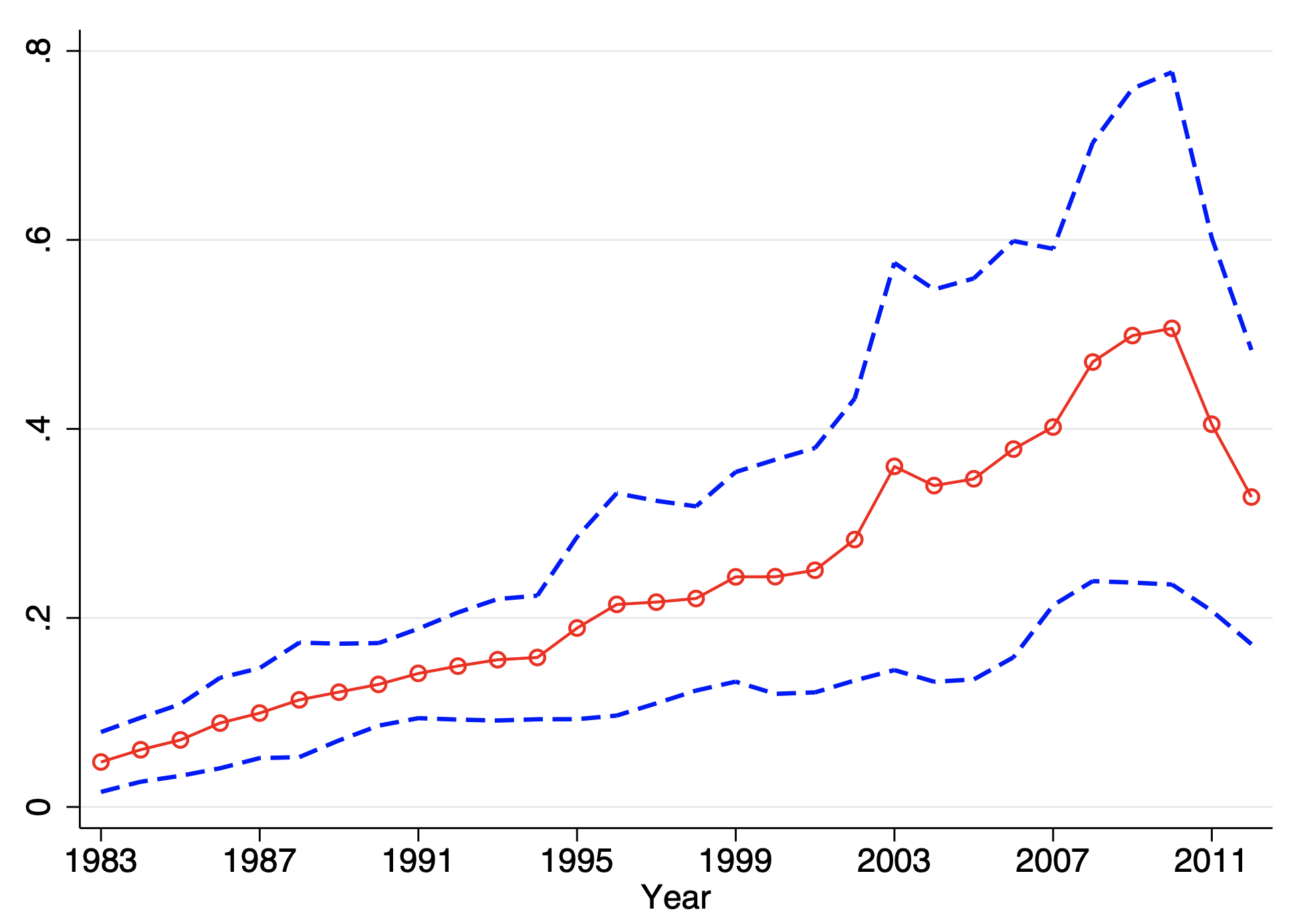

Our main empirical finding is that temporary subsidies had a large and statistically significant effect on firm sales as much as 30 years after subsidies ended. Figure 2 displays the estimate of the causal impact of credit subsidies from 1 to 28 years after they ended. The treatment effect of the subsidy is evident, and indeed the coefficient seems to rise for a couple of decades after the subsidies themselves were terminated. The effect is economically large. A firm receiving the average subsidy between 1973 and 1979 had a 919% larger sales growth between 1982 and 2009, amounting to a 8.6% higher annual growth rate over this period.3

Figure 2 The long-run impact of temporary credit subsidies on firm sales

Thus, our econometric results suggest that temporary subsidies had permanent (or at least very long-term) positive effects on the treated firms. This is indicative of some path dependence in firm outcomes. The last exercise of the paper quantifies the long-term welfare impact of the HCI Drive. We set up a general equilibrium heterogeneous firm model and discipline it using the firm-level data and econometric estimates. The model rationalises the reduced-form evidence on persistent effects of industrial policy through a combination of learning by doing (LBD) and financial constraints. There are two periods in the model. A firm's second-period productivity increases in its first-period quantity produced. However, in the first period firms are borrowing-constrained. Therefore, they cannot expand to the optimal scale to internalize the dynamic effects of LBD. Government subsidies in the first period relax these constraints, enabling firms to increase first period output, which in turn increases productivity in the second period through LBD. The model is tightly connected to the data. The key parameters of the model are pinned down by the reduced-form empirical estimates. The quantitative results imply that if the government had not conducted industrial policy, the welfare would have been 22-31% lower, depending on whether we assume that LBD-driven productivity benefits are permanent or temporary. Most of the total welfare effect (between one half and two-thirds) is due to the long-run impact of subsidies on productivity through LBD.

Summary

South Korea’s heavy and manufacturing industries is an instance in which activist industrial policy appears to have succeeded, even taking into account its fiscal costs and general equilibrium effects. While this is potentially encouraging, today’s policymakers face the same challenge as policymakers in the past: to identify conditions – such as dynamic productivity effects or externalities – under which activist industrial policy is welfare-improving.

References

Amsden, A H (1989), Asia’s Next Giant: South Korea and Late Industrialization, Oxford University Press.

Baldwin, R E (1969), “The case against infant-industry tariff protection”, Journal of Political Economy, 77(3): 295–305.

Choi, J and A A Levchenko (2021), “The long-term effects of industrial policy”, CEPR Discussion Paper 16534, September.

Heilmann, S and L Shih (2013), “The rise of industrial policy in China, 1978-2012”, China Analysis 100.

Lane, N (2019), “Manufacturing revolutions industrial policy and networks in South Korea”, Mimeo.

Lederman, D and W F Maloney (2012), “Does what you export matter? In search of empirical guidance for industrial policies”, Washington, DC: The World Bank.

Lee, J W (1996), “Government Interventions and Productivity Growth”, Journal of Economic Growth 1(3): 391–414.

Rodrik, D (1995), “Getting interventions right: How South Korea and Taiwan grew rich”, Economic Policy, 20: 53–107.

Swanson, A and K Bradsher (2021), “U.S. signals no thaw in trade relations with China”, The New York Times, 4 October.

The White House (2021), “Building resilient supply chains, revitalizing American manufacturing, and fostering broad-based growth”, 100-day reviews under executive order 14017.

Wade, R (1990), Governing the market: Economic theory and the role of government in East Asian industrialization, Princeton University Press.

Westphal, L E (1990), “Industrial policy in an export-propelled economy: Lessons from South Korea’s experience”, Journal of Economic Perspectives, 4(3): 41–59.

Endnotes

1 Wade (1990), Westphal (1990), Amsden (1989), and Rodrik (1995) argue that industrial policy played a significant role in shaping South Korea's development. However, many economists have been skeptical of the effectiveness of industrial policy (e.g. Baldwin 1969, Lederman and Maloney 2012). Lee (1996) did not find a positive correlation between sectoral TFP growth and tariff rates in South Korea during the 1970s and interpreted the correlation as the ineffectiveness of industrial policy.

2 Indeed, Korean firms that borrowed from from abroad paid negative real interest rates. The domestic real interest rates were very high due to the underdevelopment of the financial system during the 1970s.

3 Between 1982 and 2009, the real GDP of South Korea grew by 578%.