On 8 October 2018, William Nordhaus of Yale University was awarded the Sveriges Riksbank Prize in Economic Sciences in Honour of Alfred Nobel. The prize was awarded for Nordhaus’ pathbreaking work in ‘integrating climate change into long-run macroeconomic analysis’, in the words of the Nobel committee.

But his research can be seen more generally as making a profound contribution towards broadening the scope of economic analysis to shed light on the causes and consequences of how unintended effects of human activity can influence the long-run trajectory of economic growth and wellbeing. This research agenda has covered resource scarcity, economic accounting incorporating environmental considerations and, most notably, seminal work on the economics of global climate change.

The most appropriate place to start when reflecting on Nordhaus’ contributions is at the beginning of his career. He began with an interest in how innovation and technology influences growth, much like his fellow 2018 Nobel laureate Paul Romer, but then recognised that other environmental and resource challenges are equally important and interesting to study.

In the 1970s, there was great concern in both the academic community and popular press about resource scarcity – will we run out of minerals and fuels on which we rely for human wellbeing? Some of his early work sharply points out that as resources become scarce, they become more valuable, leading to further discoveries of the resources, innovation in economising on those resources, and innovation in substituting scarce resources for more plentiful – and less expensive – resources (Nordhaus 1973).

Moreover, this work emphasised that the changes in price would be expected to lead to a smooth path of resource use that allows humans to continue to maintain their wellbeing. The past several decades have largely proven Nordhaus correct, as society today is vastly more resource and energy efficient and still has ample resources at least in the foreseeable future.

But Nordhaus’ early work recognised that while resource scarcity does not present a pressing threat to long-run economic growth, the human impact on the environment provides much greater cause for worry.

In 1974, Nordhaus wrote: “I have performed a rough calculation of the atmospheric concentration of carbon dioxide… Assuming that 10% of the atmospheric carbon dioxide is absorbed annually (G. Skirrow), the concentration would be expected to rise from 340 ppm [parts per million] in 1970 to 487 ppm in 2030 – a 43% increase. Although this is below the fateful doubling of carbon dioxide concentration, it may well be too close for comfort.”

Nordhaus was prescient – it turns out we are right on track to hit 487 ppm of carbon dioxide in 2030. In two papers (Nordhaus 1975, 1977), he laid the groundwork for what is now an entire field on the economics of climate change.

In these early papers, Nordhaus began with a classic macroeconomic model of long-run growth. This groundbreaking work was the first to include a representation of carbon dioxide concentrations and the climate in such a macroeconomic framework, and to begin analysing how climate change can be mitigated at a the lowest cost possible.

This work was followed up by construction of one of the first, and the most well-known, integrated assessment model of climate change. Models are crucial for understanding the nature of climate change and how to address it because the issue involves physical, chemical and economic relationships that would simply not be possible to grasp fully without a clear framework.

Nordhaus’ first integrated assessment model – the Dynamic Integrated model of Climate and the Economy (DICE) – provides just such a framework. The single model contains all of the links among carbon dioxide concentrations, the climate, economic damages from climate change, and a model of the economy that produces carbon dioxide emissions – closing the loop (Nordhaus 1992).

Such an endeavour involved bringing physics and chemistry into economic modelling to address a critical question for policy: what is the optimal policy to address climate change?

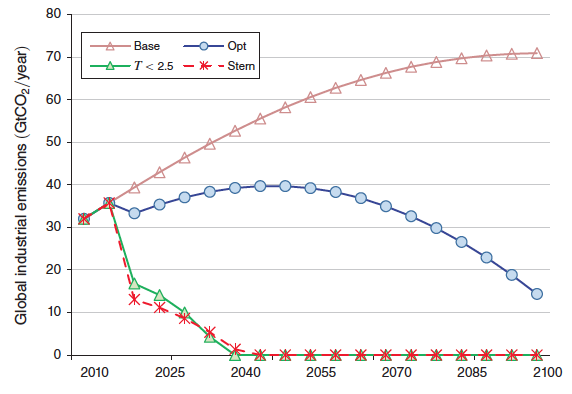

Scenarios: The Nordhaus DICE model indicates paths of future global emissions over time in a baseline no-policy scenario (Base), an optimal scenario (Opt), a scenario that keeps global temperatures from increasing more than 2.5 degrees C (T<2.5) and a scenario using a low discount rate as advocated by the Stern Review.

Source: Nordhaus (2018).

A hallmark of Nordhaus’ DICE model is that it is intentionally simple and transparent, designed to provide insights into the effects of different assumptions on the end results, which include global temperatures and global economic growth. The United Nations Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change and the US government under the Obama administration are just a few of the bodies around the world that have used DICE in their work to understand potential solutions to address climate change.

Hundreds of papers are based on the DICE model first published in 1994. The model is so clear that it is taught in courses around the country. In fact, I recall building the model in Excel from scratch as an undergraduate in the late 1990s – a transformative experience that developed intuition about the nature of the climate change issue that simply would not have been possible otherwise. An entire field of economists work with different versions of integrated assessment models of climate change, and I suspect nearly all of them began their careers working with DICE.

Developing the DICE model also spurred further contributions. For example, in 1994, Nordhaus and co-authors pioneered the estimation of the damages from climate change to agriculture (Mendelsohn et al. 1994). As the climate changes, agricultural yields may decline, reducing the value of land that now serves as cropland and, less commonly, increasing the value in some cooler climes. Such estimation allows for an empirical strategy to estimate how climate change affects agriculture in the long run. This work spawned a large set of literature on estimating the damage of climate change and many economists still work on this topic today.

Nordhaus’ contributions to the economics of climate change also extend to our understanding of uncertainty in climate change and long-run economic growth. This is one area where I have had the honour of collaborating with Nordhaus. Over the past six years, I have worked with him to understand and quantify the uncertainties inherent in climate change – what is the range of potential outcomes that might occur in the future due to climate change based on the best evidence available today?

One finding is that uncertainty in key parameters that are assumed in the models turns out to be more important than uncertainty looking across different models (Gillingham et al. 2018). What impressed me in working with Nordhaus is his ability to hone in immediately on the most essential questions, and his incredible care and meticulousness in answering them. But equally important is his joy and excitement in carrying out research and discovering new findings.

Stepping back, what makes Nordhaus’ contributions all the more notable is the deep influence they have had on policy – something that cannot be said for every Nobel laureate. Nordhaus’ research is careful and apolitical, but his work has nevertheless indirectly made its way into the policy world by influencing the thinking of generations of students.

In just one example, when I worked at the White House Council of Economic Advisers in 2015-16, there was extensive discussion at the highest levels of policy about concepts that Nordhaus helped to develop, such as the social cost of carbon, defined as the present value today of the damages of an additional ton of emissions of carbon dioxide. This social cost of carbon made its way into many regulatory impact analyses by the US government and is a topic in climate policy discussions around the world.

Nordhaus’ work has also played a more direct role through his efforts to educate sceptics on climate change, through popular books and other writings, such as his article for YaleGlobal Online in 2012.

The Nobel Prize is the most prestigious honour for research in economics, and there is no more fitting tribute to Nordhaus’ contributions. Our society will long have him to thank for expanding the domain of our knowledge to help us someday fully tackle a most pressing issue of the day: climate change.

Editor's note: This column was originally published by YaleGlobal Online at the Yale MacMillan Center.

References

Gillingham, K, W Nordhaus, D Anthoff, G Blanford, V Bosetti, P Christensen, H McJeon, andJ Reilly (2018), ‘Modeling Uncertainty in Integrated Assessment of Climate Change: A Multimodel Comparison’, Journal of the Association of Environmental and Resource Economists 5(4): 791-826.

Mendelsohn, R, W Nordhaus, and D Shaw (1994), ‘The Impact of Global Warming on Agriculture: A Ricardian Analysis’, American Economic Review 84(4): 753-71.

Nordhaus, W (1973), ‘World Dynamics: Measurement Without Data’, Economic Journal 83 (332): 1156-83.

Nordhaus, W (1974), ‘Resources as a Constraint on Growth’, American Economic Review 64(2): 22-26.

Nordhaus, W (1975), ‘Can We Control Carbon Dioxide?’, mimeo.

Nordhaus, W (1977), ‘Economic Growth and Climate: The Carbon Dioxide Problem’, American Economic Review 67(1): 341-46.

Nordhaus, W (1992), ‘The 'DICE' Model: Background and Structure of a Dynamic Integrated Climate-Economy Model of the Economics of Global Warming’, Cowles Foundation Discussion Papers No. 1009, Cowles Foundation for Research in Economics, Yale University.

Nordhaus, W (1994), Managing the Global Commons: The Economics of Climate Change, MIT Press.

Nordhaus, W (2018), ‘Projections and Uncertainties about Climate Change in an Era of Minimal Climate Policies’, American Economic Journal: Economic Policy 10(3): 333-60.

Stern, NH, et al (2006), Stern Review: The Economics of Climate Change, Cambridge University Press.