Like other professions, academia has seen remarkable progress in terms of gender equality over the last 50 years, but has not achieved parity. STEM disciplines (science, technology, engineering, and mathematics) and economics remain heavily male-dominated (Casad et al. 2021, Hengel 2017, Eberhardt et al. 2022), with men overrepresented in both academic occupations and publications (Thelwall and Mas-Bleda 2020). Paradoxically, countries with high overall levels of gender equality display greater gender disparities in STEM (see for instance Stoet and Geary 2018, 2020, and papers cited therein).

We have taken this modern gender-equality paradox and studied the presence of women in pre-industrial scientific academies and universities to search for the historical roots of women’s participation in academia.

In the past, very few women were university professors or members of scientific academies. When we started our project to build a database of European scholars in the pre-industrial era, covering both universities and academies over the period 1000–1800, we were not expecting to find any women at all. Several years into our project, we have a database with 56,000 scholars encoded manually from secondary sources, of which 108 are women. Although this is too small a number to conduct any meaningful statistical inference, there are several lessons to learn from these 108 scholars (De la Croix and Vitale 2022).

Figure 1 Luisa de Medrano, Professor at the University of Salamanca (1508). Detail of a painting by Juan de Pereda, the Sibyls of Atienza

There have been women in academia since universities were first founded during the 11th century. Trotula de Ruggiero (physician, Salerno) and Accursia (law, Bologna) are two examples. Even though some of these figures might be more legendary than real, the fact that they are legends is telling. More certain is the existence of a few women scholars from the 15th century; for example, Luisa de Medrano in Spain (Figure 1).

Academies of Sciences and Arts were not indifferent to the great erudition of some women. As these academies expanded in the 17th and 18th centuries, some women scholars were elected academicians.

The women we identified did not always hold formal, full-professor positions in universities. Sometimes, they participated as a replacement teacher or an invited lecturer. In academies, they were sometimes elected members without the capacity to actually participate in meetings.

From the quantitative analysis of the data we collected, and the qualitative analysis we conducted on the biographies of most of the women in our database, we made three findings.

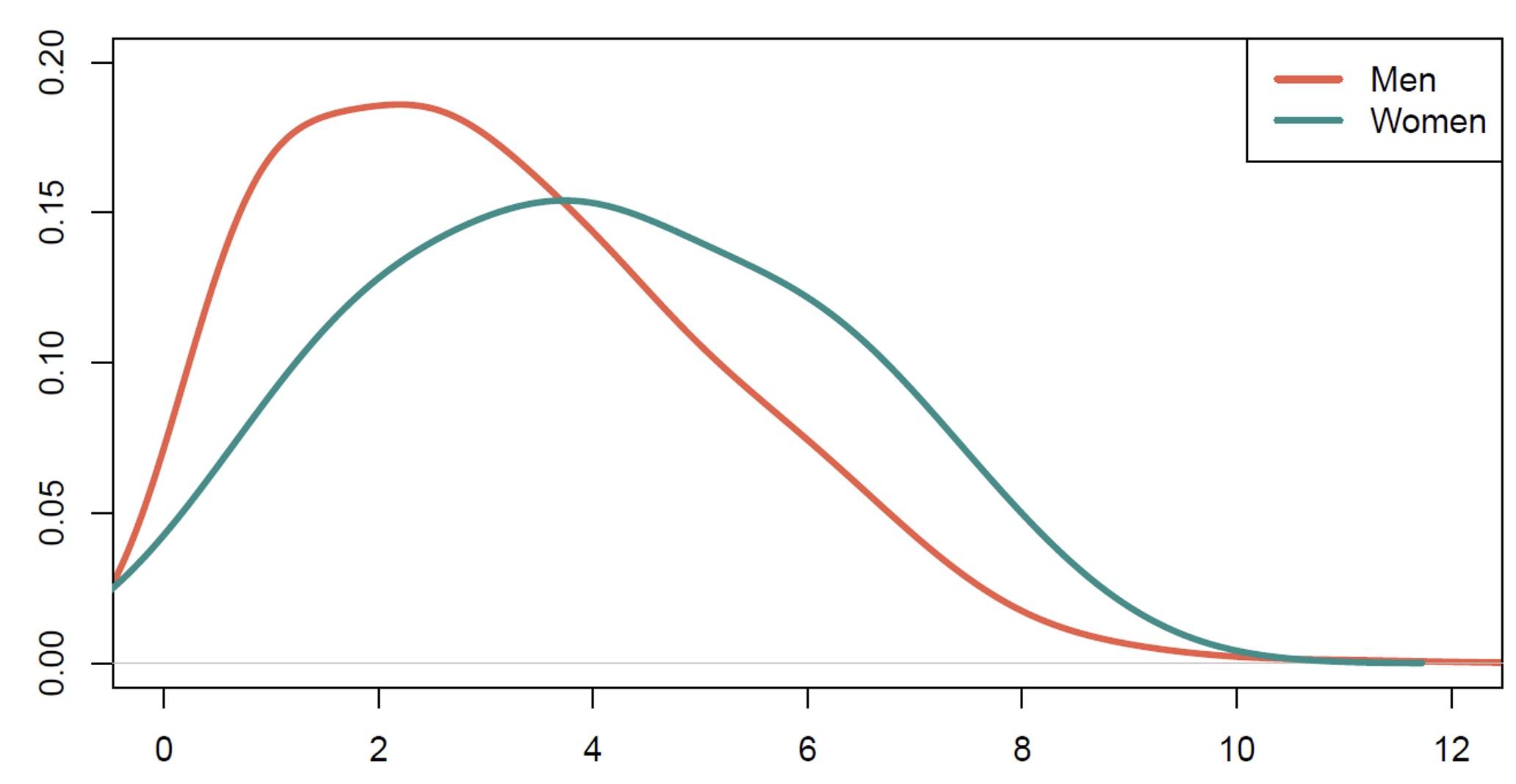

The first concerns publications. Calculating the quality of the scholars from their publications in the catalogue of libraries today (Worldcat), we find that the 84 women who have published some work are on average better than the 20,984 published males. Figure 2 shows the probability density functions of the publication-based measure of human capital for both men and women. The median human capital is 3.91 for women and 2.85 for men. Such a gap could reflect discrimination: to be hired, a woman had to overcome negative views about women by being considerably better than the median man, translated here into additional publications.

Figure 2 Probability density function of publication-based human-capital index for men and women academic scholars

Secondly, as stressed by Nekoei and Sinn (2021), women’s power has sometimes been a side-effect of nepotism: we find many wives, daughters of professors, or women whose family networks were large and influential. The share of these women who married is about the same as in the general population, but a disproportionate share of the women remained childless. This can be explained partly by the fact that marriage enabled them to continue their intellectual activity without being subjected to a community's negative judgments. Sometimes these scholars shared their scholarly activity with their husbands, as in the cases of Laura Bassi and Anna Morandi Manzolini in Bologna (Figure 3). In the Protestant world, we found that women were often the assistants to their husbands, fathers, or brothers (as, for example, was Maria Winkelmann-Kirch). Despite their active participation in scientific discoveries, they were never given a place in their own right at academies or universities.

Figure 3 Wax Self-Portrait of Anna Morandi with Brain; Poggi Museum, Bologna

Notes: Anna Morandi taught anatomy at the University of Bologna from 1756 to 1774. She was an internationally known anatomical wax modeler (photo: D. de la Croix).

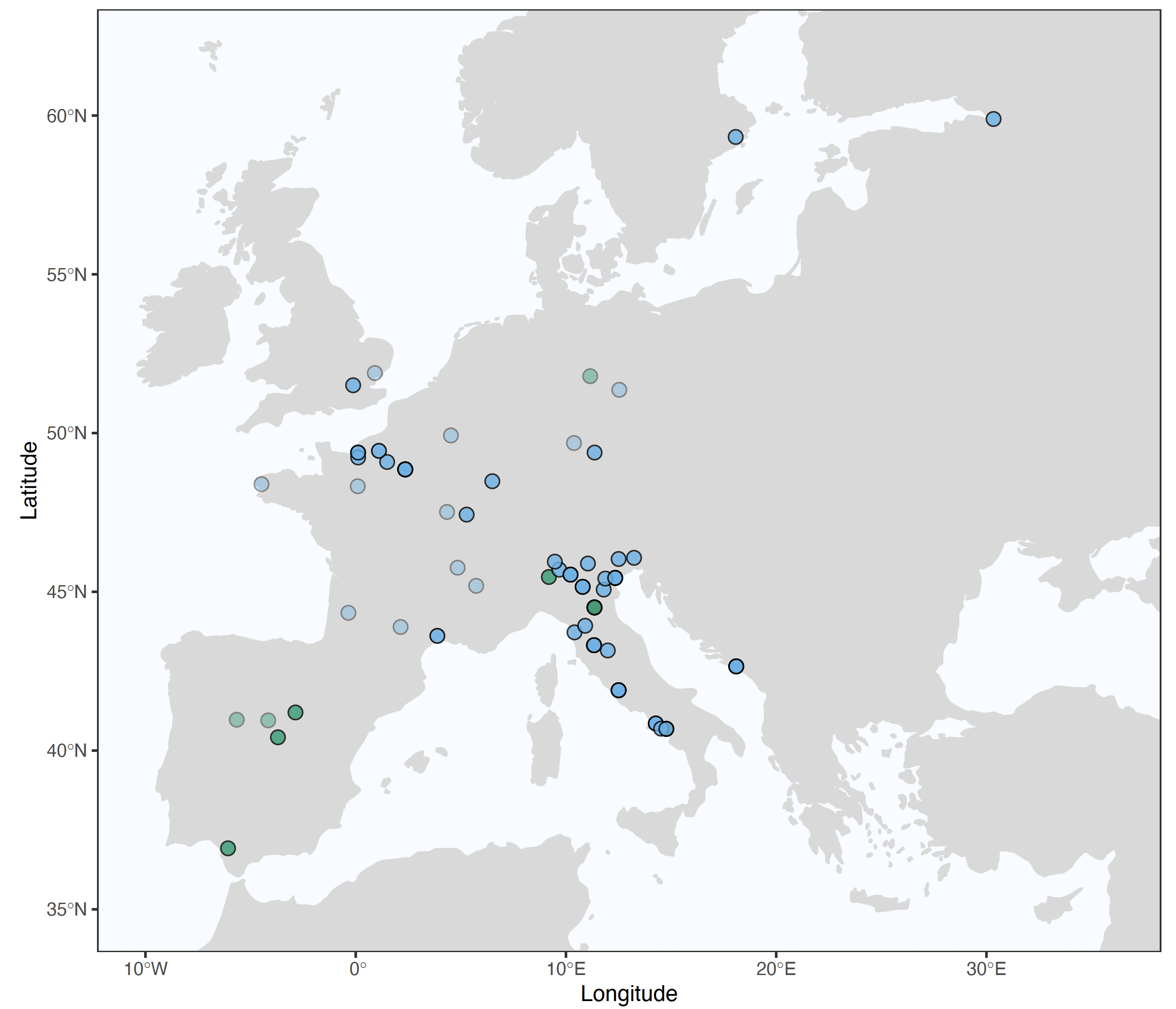

A noteworthy observation in our research is that most of the women we found were affiliated with Catholic institutions. Figure 4 shows the birthplace of women professors (green) and academicians (blue). Lighter colours indicate a weak link, such as being a corresponding member of an academy. Very few women were members of Protestant institutions: Eva Ekeblad was the first woman to be admitted to the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences, for discovering how to make alcohol out of potatoes. Ekaterina Romanovna Dasjkova is linked to both the Royal Swedish Academy and the Leopoldina. Hedvig Gustava Malmsten was elected full member of the Royal Physiographic Society in Lund, Sweden, by mistake: the statutes stipulated that only men could be members of the society.

To explain the presence of these women in academic institutions, we first considered the autonomy of the institutions. Many protestant universities in Germany were founded in a top-down fashion, whereas early universities such as Bologna and Paris grew from the bottom up. In Germany, the Prince had more control and institutions made fewer autonomous and anti-conformist decisions, such as welcoming women to a university. However, this does not explain why English and Scottish academia remained closed to women.

Figure 4 Places of birth of women academic scholars

Note: Blue: academicians. Green: professors. Light colour: weak links.

We hypothesised that religion might explain this difference between northern and southern Europe, and scrutinised the differences between religious denominations. There is a tendency to think that Protestantism brought a wave of modernity. This is only partly true. Luther is thought to have fostered the emancipation of women by allowing them to attend school, and after the Reformation more women received an education in Protestant countries than in Catholic countries. However, we know that education only covered the basics and that the shift towards emancipation was slight (Roper 1989).

On the whole, Protestant social norms for women were not very different from Catholic norms. The substantial difference was in the formal centralisation of decision making. The Catholic Church could control women’s participation in public space – and it could also make exceptions, which allowed these notable women to emerge. Women in Protestant communities were subject to the judgement and will of their husbands and fathers in the home, and it was difficult for them to achieve visibility in public spaces.

In considering the reasons for this unusual pattern, we also considered culture and theology. In particular, we noted that Marian devotion is fundamental for Catholics but considered a form of idolatry among Protestants. Thus, Catholics have an inspiring woman role model, while Protestants are discouraged from giving her special attention. For Catholics, Mary’s out-of-the-ordinary gifts grant her notoriety and consideration on par with men. The exceptional intellectual gifts of particular women convinced religious authorities to make exceptions and allow some women to become university professors. The intellectual exceptionality of certain women offered some religious and political authorities an opportunity to promote their politics. This is the case for Cardinal Lambertini with Laura Bassi (professor in Bologna) and Charles III with Maria Isidra Guzman (professor in Alcalá). Hence, the most convincing difference for us is the capacity of Catholic institutions to tolerate exceptions.

Finally, our data challenge the popular idea that the little divergence between Northern and Southern Europe was driven by Protestantism. Nuno et al. (2022) have shown that Protestant countries did not display a more growth-promoting marriage pattern (contrary to a view promoted in previous research). Here we challenge the idea that Protestantism was necessarily more modern and more liberal than Catholicism, at least where the participation of women in upper-tail human capital is concerned.

Authors’ note: This project has received funding from the European Research Council (ERC), under the European Union's Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme in grant agreement No 883033, “Did elite human capital trigger the rise of the West? Insights from a new database of European scholars”. We are grateful to Davide Cantoni for directing us to think about the gender-equality paradox. We also thank Per Alm, the Permanent Secretary and Treasurer of the Royal Physiographic Society in Lund, for his help with the difficult case of Hedvig Gustava Malmsten.

References

Casad, B J et al. (2021), "Gender inequality in academia: Problems and solutions for women faculty in STEM", Journal of Neuroscience Research 99 (1): 13–23.

De la Croix, D and M Vitale, (2022), “Women in European Academia before 1800 - Religion, Marriage, and Human Capital”, CEPR Discussion Paper No. 17229.

Eberhardt, M, G Facchini and V Rueda (2022), “Women are ‘hardworking’, men are ‘brilliant’: Stereotyping in the economics job market”, VoxEU.org, 08 February.

Hengel, E (2017), “Evidence from peer review that women are held to higher standards”, VoxEU.org, 22 December.

Nekoei, A and F Sinn (2021), “The origin of the gender gap”, VoxEU.org, 27 May.

Stoet, G and D C Geary (2018), "The gender-equality paradox in science, technology, engineering, and mathematics education", Psychological Science 29 (4): 581–593.

Thelwall, M and A Mas-Bleda, (2020), "A gender equality paradox in academic publishing: Countries with a higher proportion of female first-authored journal articles have larger first-author gender disparities between fields", Quantitative Science Studies 1(3): 1260–1282.

Palma, N, J Reis and L Rodrigues (2022), “Historical gender discrimination does not explain comparative Western European development”, VoxEU.org, 27 February.

Roper, L (1989), The holy household: women and morals in Reformation Augsburg, Clarendon Press.