Consistent with the recent increase in consumer price inflation and in light of persistent or even intensifying supply shortages, the ECB’s inflation projections have been revised upwards twice since December 2021. In particular, the current-year outlook for 2022 was raised substantially from 1.7% to 3.2% in December 2021, to 5.1% in March 2022, and then to 6.8% in June 2022. It was also recognised that bringing inflation back down may take somewhat longer, as the projection for 2023 was revised from 1.8% to 2.1% and then to 3.5% in June. Nevertheless, the ECB/Eurosystem staff projections still see inflation to converge towards the ECB’s 2% target in the medium term, with the outlook for 2024 being revised from 1.8% in December to 1.9% and 2.1% in March and June, respectively.1

Inflation expectations of German households have also increased substantially since 2021.2 The median of expected inflation for the next 12 month has risen steadily from 2% in January 2021 to 5% in February 2022, and recently jumped to 8% in June 2022. While inflation expectations five and ten years ahead have also increased substantially, they remain at somewhat lower levels of 5% and 4%, respectively.

In our analysis, we study two aspects of the expectation formation process of households. First, we analyse whether households consider current high inflation rates as a transitory phenomenon or a permanent development. We elicited roughly 5,000 joint responses on future inflation rates from the March 2022 wave of the Bundesbank Online Panel Households (BOP-HH). Each survey respondent was asked to cast probabilistic assessments for inflation over the next 12 months (short term), two-to-three years (medium term), and five-to-ten years ahead (the longer term). Second, we assess whether ECB communication about the medium-term inflation outlook effectively reduces household inflation expectations. Combined, the survey questions thus allow us to study households’ expected inflation path and how it is affected by central bank communication.

We designed the survey questions as a randomised control trial (RCT). In a first step, we informed all respondents about the inflation target. Then, we asked them to assign probabilities that the realisation of medium-term inflation will fall into certain pre-specified intervals. We restricted the replies so that reported probabilities had to sum up to 100. In a second step, respondents were randomly selected into several groups which received different variations of quantitative and qualitative ECB communication about projected inflation in the medium term. A control group did not receive any communication. Finally, all respondents were again asked about inflation one year, two-to-three years, and five-to-ten years ahead.

Specifically, two groups received quantitative information about the ECB’s inflation projections published in March 2022. In addition, one of the two groups (labelled `quantitative strong’ in the charts below) received information about the revision from the December 2021 projections. Two further groups were shown verbal explanations of the ECB inflation projections by chief economist Philip Lane, which have also been cited in various media reports. One group (labelled ‘qualitative’) was given information that Lane expected inflation rates to fall over the course of 2022 and that inflation in 2023 and 2024 would decline below the inflation target. The other group additionally was provided with a statement that Lane did not see any evidence (yet) of second round effects.

Do private households consider the current high inflation rates as a transitory phenomenon or a permanent development?

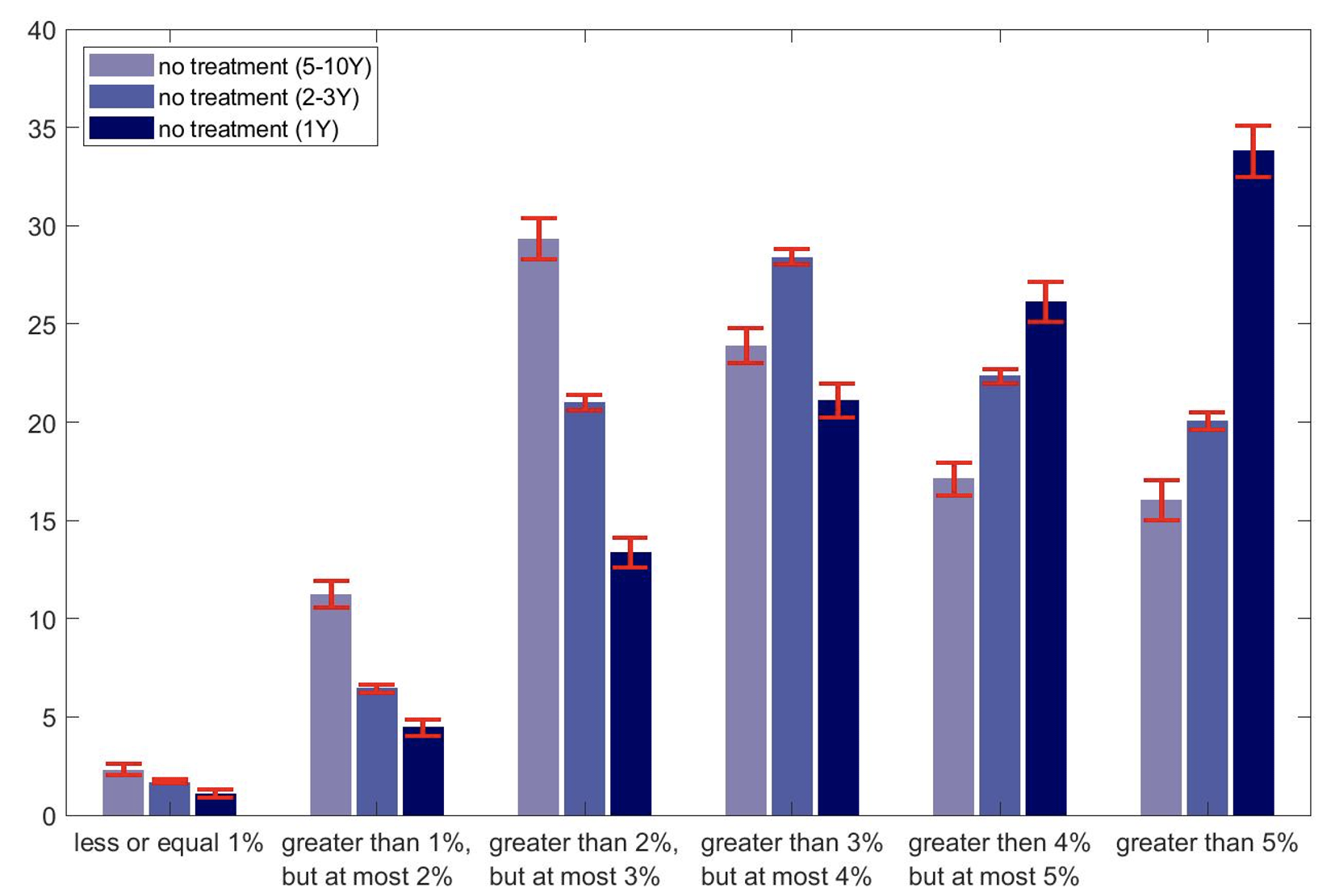

Figure 1 Households’ average subjective probabilities for short, medium, and longer-run inflation rates

Notes: One standard error bars are plotted in red.

Figure 1 shows households’ average reported probabilities for the short (dark blue), medium (medium blue), and longer run (lighter blue) inflation rates before being shown ECB communication on the inflation outlook. Inflation expectations for the short term are strongly tilted to the upside, with respondents on average assigning a one-third chance to inflation above 5% and allocating roughly 80% of the probability mass to inflation above 3%. For the medium-term, however, inflation expectations are substantially lower. At the ten-year horizon, inflation expectations are even lower, but much of the mass remains above the 2% inflation target of the ECB. We infer from the figure that German households perceived the high inflation as largely transitory in March 2022, but also saw significant risks that inflation would remain above the ECB's target for a longer period of time.

Is central bank communication able to steer households’ inflation expectations?

Based on these findings, we would like to understand whether ECB communication is effective in bringing these expectations closer to the inflation target. To this end, we compare the reported inflation paths for the different groups of randomly sampled respondents before and after showing them the quantitative or qualitative communication on the ECB’s inflation outlook.

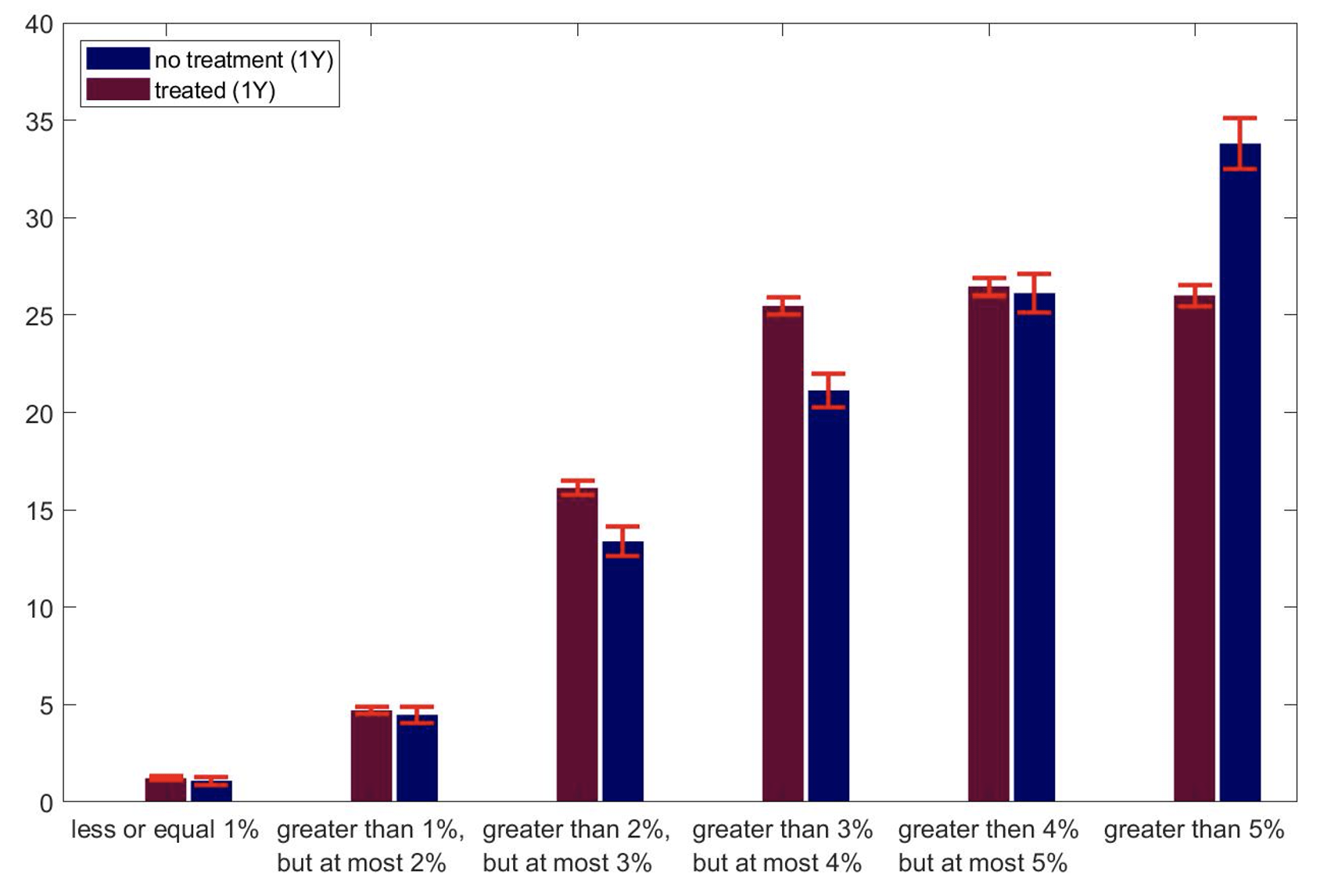

Figure 2 One year ahead inflation expectations for respondents with and without communication treatment

Notes: This figure presents one year ahead inflation expectations for respondents without treatment (dark blue) and for all respondents pooled that received communication treatment (dark red). One standard error bars are plotted in red.

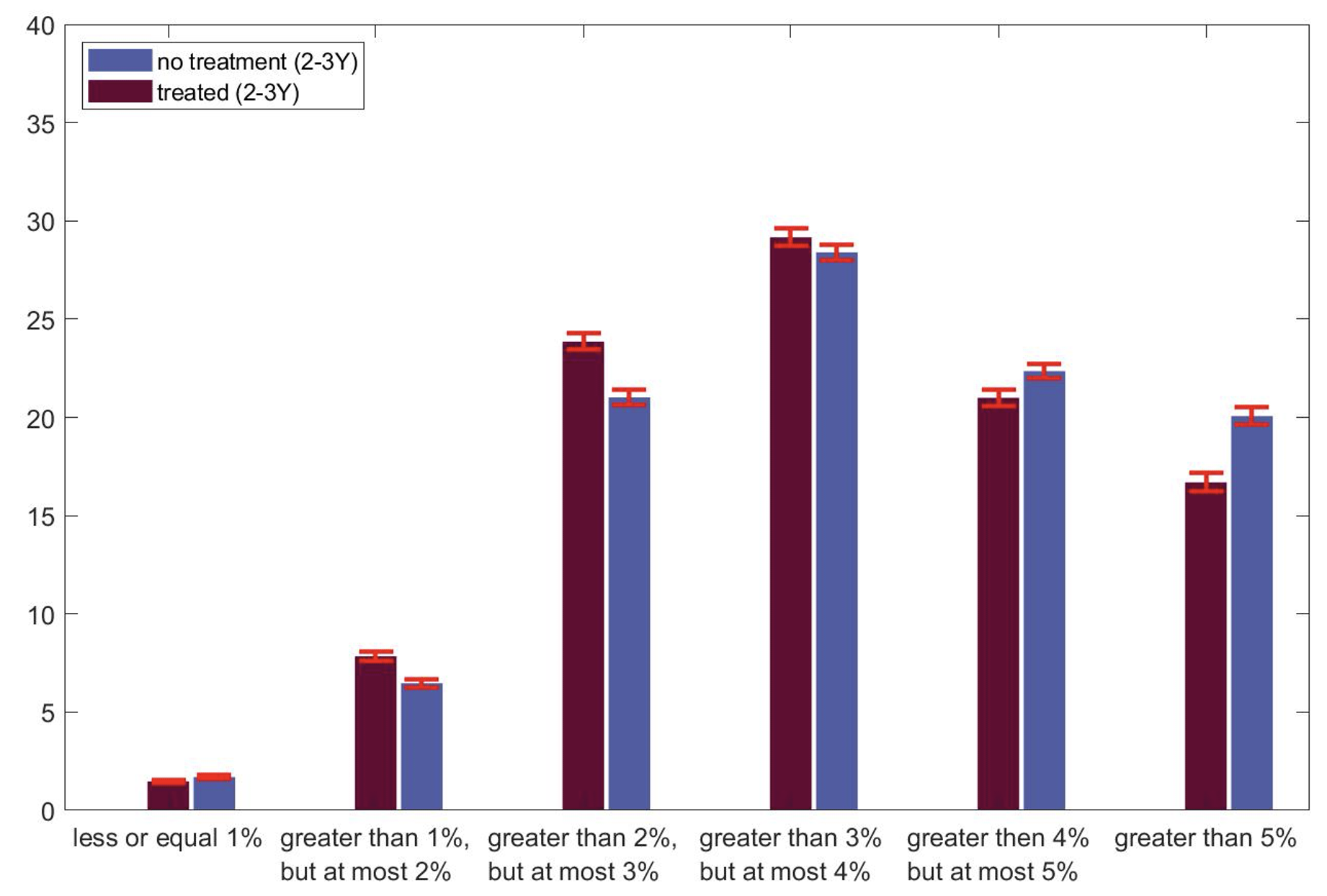

Figure 3 Two-three years ahead inflation expectations for respondents with and without communication treatment

Notes: Two-three years ahead inflation expectations for respondents without treatment (medium blue) and for all respondents pooled that received communication treatment (dark red). One standard error bars are plotted in red.

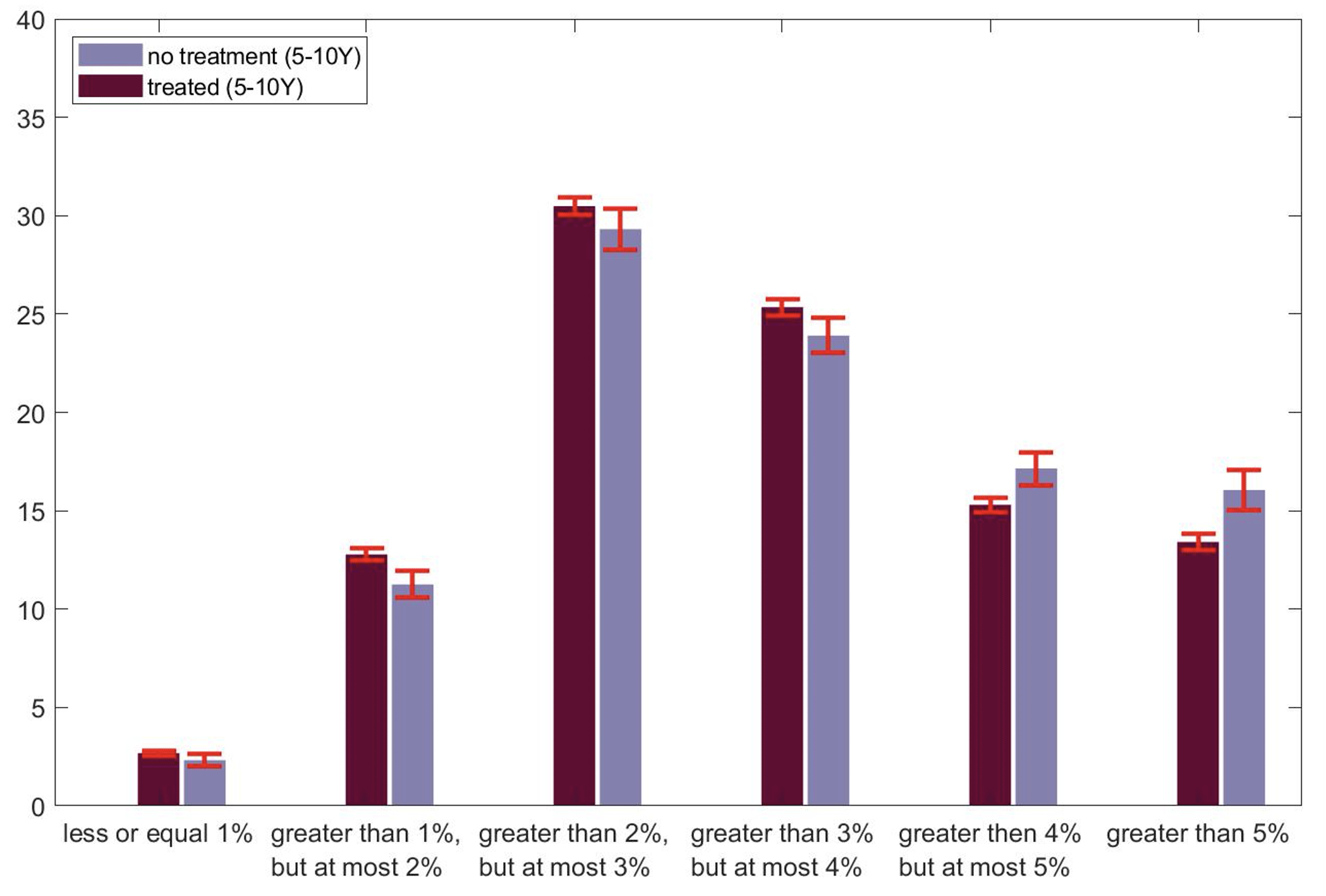

Figure 4 Five-ten years ahead inflation expectations for respondents with and without communication treatment

Notes: Five-ten years ahead inflation expectations for respondents without treatment (lighter blue) and for all respondents pooled that received communication treatment (dark red). One standard error bars are plotted in red.

Figures 2–4 contrast the average subjective probabilities before the information treatment (in blue) with the average reported probabilities of respondents that received either of the two types of information (in red). Figure 2 displays the one year ahead expectations, showing that in particular very high inflation outcomes were assessed to be less likely by households after receiving information on the inflation outlook. This is also the case for medium-term expectations, shown in Figure 3, albeit to a lesser degree. Figure 4 shows that for longer-run expectations, the provided information further reduces expected inflation rates in the right tail of the distribution.

We now assess the effects of the different variants of provided communication on the reported inflation expectations. Specifically, for each expectation horizon, we regress the mean inflation expectations for each individual post-treatment on an intercept and a set of dummy variables that indicate the specific treatment groups the respondents were sampled into. This allows us to disentangle the term structure of expected inflation for the control group, as captured by the estimated intercept, from the changes in expected inflation induced by the different pieces of ECB communication, as captured by the coefficient estimates on the dummy variables.

We highlight three findings from our regression analysis. First, we observe that the term structure is downward-sloping, with the average expected inflation rate declining from 4.28% at the one-year horizon to 3.78% and 3.38% at the two- to three-year and the five- to ten-year horizons, respectively. While this 90 basis point reduction is sizeable, average inflation expectations remain elevated even in the longer run. Second, the estimated treatment effects are all negative and (with one exception) highly statistically significant. This implies that the ECB’s communication can be effective in lowering above-target inflation expectations.

Finally, comparing the estimated treatment effects, we observe that the qualitative information has a substantially stronger impact than the quantitative information. While the first lowers expectations by roughly 47 basis points for the current year, 28 basis points for the medium term, and 23 basis points for the longer term, the latter only achieves reductions of roughly 17 basis points, 18 basis points, and 11 basis points, respectively. In a related context, Draeger et al. (2022), observe that showing forecasts from professional forecasters (SPF) to survey participants who are primed only on high inflation rates rather than the ECB’s inflation target tend to reduce only short-run inflation expectations. Moreover, they find a rather limited effect of text-based communication on respondent’s expected inflation.

Extending the communication treatments with more suggestive elements, such as adding the projection revision in the case of `quantitative strong’ or mentioning yet unobserved second-round effects in `qualitative strong’, does not further amplify the treatment effects. These results might imply that survey respondents are willing or able to process only a limiting amount of text. This is consistent with Coibion et al. (2019a, 2019b), who find that detailed information about the Federal Open Market Committee’s decisions does not affect households’ inflation expectations differently than simply providing them with the FOMC’s forecasts. Recent results from Hwang et al. (2022a, 2022b) further suggest that more detailed central bank communication might even be detrimental to trust in the ECB. In our analysis, however, we observe that higher levels of trust are associated with stronger effects of ECB communication on households’ inflation expectations. This latter result is in line with our earlier work which showed that informing private households about the ECB’s monetary strategy can effectively guide their expectation formation process, and that households with higher levels of trust in the central bank adjust their expectations more strongly (Hoffmann et al. 2021a, 2021b).

Overall, our observations underline that targeted central bank communication can be effective in reducing private sector inflation expectations in times of high inflation. Moreover, verbal ex-planations of the inflation outlook seem to have larger effects than providing quantitative assessments. Former policymakers themselves have acknowledged that ECB communication with the general public can be improved, for instance via social media, as described by Ehrmann et al. (2021, 2022). Moreover, verbal explanations seem to offer better means to address the “discrepancies in households’ knowledge […] of monetary policy”, (Van der Cruijsen et al. 2015a, 2015b). While more research along these lines is needed, our findings may provide some further guidance on potential directions for such improvements.

References

Coibion, O, Y Gorodnichenko and M Weber (2019a), “Monetary policy communications and their effects on household inflation expectations”, VoxEU.org, 22 February.

Coibion, O, Y Gorodnichenko and M Weber (2019b), “Monetary Policy Communications and their Effects on Household Expectations”, NBER Working Paper 25482.

Hwang, I D, T Lustenberger and E Rossi (2022a), “Some unpleasant speaking arithmetic: ECB speeches and trust”, VoxEU.org, 11 July.

Hwang, I D, T Lustenberger and E Rossi (2022b), “Central Bank Communication and Public Trust: The Case of ECB Speeches”, SSRN Working Paper, 15 June.

Draeger, L, M J Lamla and D Pfajfar (2022), “How to Limit the Spillovers from the 2021 Inflation Surge to Inflation Expectations”, Leibniz University Hannover Discussion Paper 694.

Ehrmann, M, S Holton, D Kedan and G Phelan (2021), “Monetary policy communication: perspectives from former policy makers at the ECB”, CEPR Discussion Paper No. 16816.

Ehrmann, M, S Holton, D Kedan and G Phelan (2022), “Views on monetary policy communication by former policymakers”, VoxEU.org, 17 January.

Hoffmann, M, E Moench, L Pavlova and G Schultefrankenfeld (2021a), “The effects of the ECB’s new inflation target on private households’ expectations”, Bundesbank Research Brief, 43rd edition, November.

Hoffmann, M, E Moench, L Pavlova and G Schultefrankenfeld (2021b), “The effects of the ECB’s new inflation target on private households’ expectations”, VoxEU.org, 20 December.

Van der Cruijsen, C, D-J Jansen and J de Haan (2015a), “What the general public knows about monetary policy”, VoxEU.org, 23 August.

Van der Cruijsen, C, D-J Jansen and J de Haan (2015b), “How Much Does the Public Know about the ECB’s Monetary Policy? Evidence from a Survey of Dutch Households”, International Journal of Central Banking 11(5): 169-218.

Endnotes

1 The ECB publishes a collection of the ECB/Eurosystem Staff Macroeconomic Projections under https://www.ecb.europa.eu/mopo/strategy/ecana/html/table.en.html

2 Further information on German households’ inflation expectations is provided under https://www.bundesbank.de/en/bundesbank/research/survey-on-consumer-expectations/inflation-expectations-848334