Most measures to control the COVID-19 pandemic are not only economically disruptive, they are centuries old (Baldwin and Weder di Mauro 2020). And while applying quarantines and social distancing is effective from a public health perspective, the economic consequences are more severe for today’s economies, where most workers leave their home nearly every day to do their job. This differs from the times of the Spanish Flu, when production was largely home-based, with families producing goods for their own consumption or as a source of income. Yet prior to the COVID-19 pandemic, the proportion of home-based workers across the world was relatively low, and where it was most prominent, it continued to be associated with cottage industries or industrial homework.

Information and communication technology (ICT) offers us a ‘modern tool’ to fight the pandemic. ICT facilitates working from home, allowing countries to not only safeguard public health, but also to help safeguard their economies. It is thus not surprising that governments across the world have encouraged employers to allow their workers to work from home, where possible. Still, the potential for working from home varies across the world, as a result of differences in occupational structure, but also the infrastructure available to support working remotely.

Working from home prior to COVID-19

Prior to the COVID-19 pandemic, the ILO estimates that 7.9% of the world’s workforce (260 million workers) worked from home on a permanent basis. (See figure 1). Although some of these workers were ‘teleworkers’, most were not, as the figure includes a wide range of occupations including industrial outworkers (e.g. embroidery stitchers, beedi rollers), artisans, self-employed business owners and freelancers, in addition to employees. Employees accounted for one out of five home-based workers worldwide, but this number reaches one out of two in high-income countries. Globally, among employees, 2.9% were working exclusively or mainly from their home before the COVID-19 pandemic.

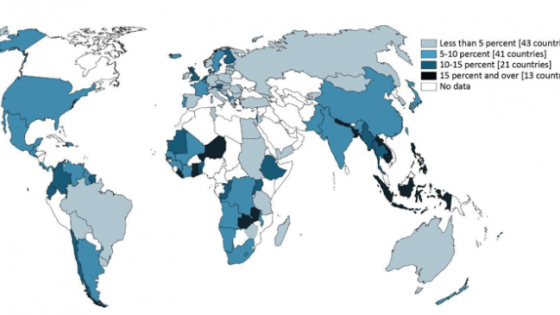

Figure 1 Percentage of workers that were home-based (all employment statuses) prior to pandemic

Note: This figure includes all types of home-based workers, including teleworkers. These estimates are based on labour force survey data from 118 countries representing 86% of global employment. Data are from 2019 or latest year available.

Source: ILO (forthcoming).

With the COVID-19 pandemic, the percentage of workers teleworking has risen tremendously. A 23 March survey of 250 large firms in Argentina found, for example, that 93% had adopted teleworking as a policy in response to the COVID-19 pandemic.1 But the adjustment to teleworking is not always so straightforward. While many companies recognise the benefits of teleworking, some have had difficulty making the transition. In Japan, for example, a survey conducted by the Japan Association for Chief Financial Officers of 577 CFOs and finance directors prior to the 7 April announcement of the State of Emergency found that while 96% respondents agreed with the importance of teleworking, 31% of companies were unable to adopt teleworking because paperwork was not yet digitised and internal rules and procedures necessary for teleworking were not ready.2 Concerns over confidentiality of information or possible security breaches can also limit the use of teleworking. In addition, the economic contraction is affecting the demand for both industrial homeworkers and teleworkers, so even if the worker could do their job from home, they may not be able to (von Broembsen 2020).

Studies estimating the potential to work from home

Since the beginning of the pandemic, there has been a remarkable volume of research on the potential for home-based work as a crisis response. Dingel and Neiman (2020) use occupational descriptions from the Occupational Information Network (O*NET) to estimate the degree to which different occupations in the United States can be done remotely. Their preferred estimate is that 34% of American jobs “can plausibly be performed from home”.3 Albrieu (2020), Foschiatti and Gasparini (2020) and Guntin (2020) apply Dingel and Neiman’s methodology to Argentina and Uruguay, respectively. They conclude that from 26% to 29% of Argentinian, and between 20% and 34% of Uruguayan workers, are in occupations that can be done remotely. Finally, Boeri et al. (2020) use a slightly adapted methodology to estimate the home-based work potential as 24% for Italy, 28% for France, 29% for Germany, 25% for Spain, and 31% for Sweden and the UK.

Variations on Dingel and Neiman’s methodology have dominated the literature, possibly since they rely on a reasonably objective measure of whether each occupation can be done from home or not. The limitation of this methodology is that O*NET data are for the US and can, at most, be used for economies whose work environment is similar. Gottlieb et al. (2020) use Dingel and Neiman’s methodology, but focus on the agricultural sector and show that different estimates for agriculture may change radically the percentage of jobs that can be done from home in the developing world. Saltiel (2020) uses the STEP Skills Measurement Program to estimate home-based work probabilities for developing countries, but does not really consider industrial homeworkers so prevalent in some developing countries.

The potential for working from home across the globe: Delphi survey findings

To estimate the share of workers who could potentially work from home if necessary around the globe, we used the Delphi research method and asked labour market experts from around the world to estimate for their country or region, the share of workers by three-digit occupation who could potentially work from home. We then use these estimates and the occupation profile for each country to calculate a final estimate of the number of workers who can work from home.

According to our calculations, close to 18% of workers work in occupations and live in countries with the infrastructure that would allow them to effectively perform their work from home (ILO 2020). Not surprisingly, there are important differences across regions of the world and income level of each country, reflecting the economic and occupational structures of countries, but also environmental factors, such as access to broadband internet and likelihood of owning a personal computer, whether the housing situation allows working from home, or whether the person has fixed clients, for other types of home-based work.

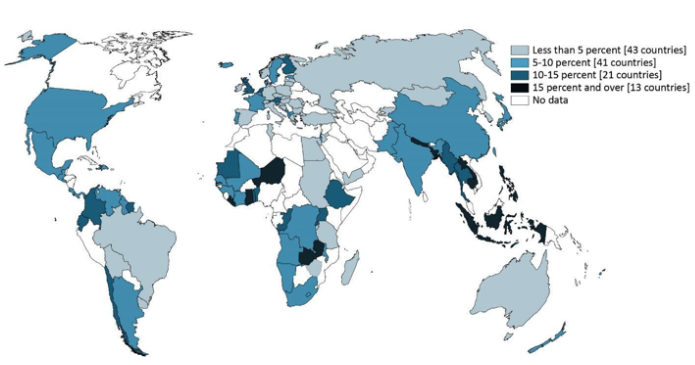

Figure 2 Home-based work estimates

Observation: World Bank country groupings.

Source: Delphi questionnaires.

That workers in developed economies are more capable of working from home is not a surprise. Many workers in developing nations are employed in occupations that cannot be done from home, and these occupations are more common. It is six times more common to be a street vendor in a low-income country than in a high-income country, and 17 times more common to be an agricultural labourer. Such differences in occupational structure alone account for a difference of ten percentage points between workers in advanced economies and developing ones (13% for developing economies against 23% for developed ones). In addition, the social, physical, and information technology infrastructure is often less adapted to home-based work in developing countries than in developed ones. If these differences are taken into consideration, the difference between low- and high-income countries increases from 10 to 15 percentage points.

Figure 2 shows two numbers. The light coloured bars titled “Group-Specific Probabilities” show the proportion of the labour force that could work from home. The variation between them takes into account both changes in occupational structure and in underlying social and physical infrastructure. The darker bars entitled “Global Probabilities” show the proportion of workers that could work from home if all countries had the same occupation-specific work from home probabilities. In other words, it shows the variation that stems only from changes in the occupation structure.

There are also regional variations that closely follow income variations. According to our estimates, around 30% of North American and Western European workers are in occupations that allow home-based work, as opposed to only 6% of sub-Saharan African and 8% of South Asian workers. Latin American and Eastern European workers fall somewhere in between at 23% and 18%, respectively.

Working from home: Ensuring decent work for COVID-19 teleworkers

While working from home is an important measure for mitigating the COVID-19 pandemic, attention should be paid to ensure that working conditions do not deteriorate. The ILO’s Home Work Convention, 1996 (No. 177) calls for equality of treatment between homeworkers and other wage-earners in relation to freedom of association and collective bargaining, wages and benefits, access to training, OSH and social protection. While the Convention does not apply to employees who occasionally perform their work at home as employees, it does include employees who perform their work at home on a regular basis. Since many of the COVID-19 homeworkers are working from home on a regular and extended basis, telework as a response to the COVID-19 pandemic would likely be recognised as falling within the scope of C177.

Of concern are the implications of working from home for work-life balance, which may be difficult to manage particularly if children or other dependents require attention; it may also potentially lead to discrimination against workers with care responsibilities. The overlap between paid work and personal life can have negative effects for workers (particularly women, who still undertake the largest share of care-related tasks), but also for enterprises, if it negatively impacts productivity. Managing these possible tensions at the firm level through social dialogue between management and workers’ representatives, but also at the policy level, is critical.

References

Albrieu, R (2020) “Evaluando las oportunidades y los límites del teletrabajo en Argentina en tiempos del COVID-19”, Buenos Aires: CIPPEC.

Baldwin, R and B Weder di Mauro, (2020) “Introduction”, in R. Baldwin and B. Weder di Mauro (eds), Economics in the Time of COVID-19, a VoxEU.org eBook, CEPR Press.

Boeri, T, A Caiumi and M Paccagnella (2020) “Mitigating the work-safety trade-off,” Covid Economics: Vetted and Real-Time Papers 2, 8 April.

Dingel, J and B Neiman (2020) “How Many Jobs Can be Done at Home?,” Covid Economics: Vetted and Real-Time Papers 1, 3 April.

Fadinger, H and J Schymik (2020) “The Effects of Working from Home on Covid-19 Infections and Production: A Macroeconomic Analysis for Germany,” CRC Discussion Paper No 167.

Foschiatti, C B and L Gasparini (2020) “El Impacto Asimétrico de la Cuarentena: Estimaciones en base a una caracterización de ocupaciones,” CEDLAS Working Paper No. 261.

Gottlieb, C and J Grobovsek and M Poschke (2020) “Working from Home Across Countries,” Covid Economics: Vetted and Real-Time Papers 8, 22 April.

Guntin, R (2020) “Trabajo a Distancia y con Contacto en Uruguay”, mimeo.

ILO (2020) "Working from Home: Estimating the worldwide potential", ILO policy brief.

ILO (forthcoming) The home as workplace: Trends and policies for ensuring decent work.

Leibovici, F, A M Santacreu and M Famiglietti (2020) “Social Distancing and Contact-Intensive Occupations”. Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis.

Mongey, S and A Weinberg (2020) “Characteristics of Workers in Low Work-From-Home and High,” Becker Freidman Institute for Economics at UChicago White Paper.

PNUD-Pacto Global (2020), “ENCUESTA : Respuestas de las empresas argentinas ante el impacto de la cuarentena general en sus operaciones,”, 30 March.

Saltiel, F (2020) “Who can Work from Home in Developing Countries?”, mimeo.

Von Broembsen, M (2020) “The world’s most vulnerable garment workers aren’t in factories – and global brands need to step up to protect them,” WEIGO blog

Endnotes

1 This does not imply, however, that all staff could continue in their functions. Only 48% of firms were able to continue normal operations; 60% had partially or completely suspended their activities. Nevertheless, for those staff who continue duties from home, these companies well able to make the shift to remote work (PNUD 2020).

2 See http://www.cfo.jp/wordpress/wp-content/uploads/2020/04/release_200406.pdf

3 Other studies on the US include Leibovici et al. (2020) and Mongey and Weinberg (2020); these studies rely on the O*NET source as well as descriptions on whether jobs require personal contact.

4 We received 23 estimates for 19 countries and two regions. For details on the methodology and results see ILO (2020).