The COVID-19 pandemic caused large and sustained disruption in labour markets in the US. Millions of workers lost their jobs, while many others maintained their jobs but necessarily shifted to working from home. Working parents were thrust into the particularly challenging situation of having to contend with school and daycare closures. Fewer than half of US K-12 students had returned to all in-person learning by January 2021, and fewer than two-thirds had fully returned to in-person instruction by May 2021 (US Department of Education, Institute of Education Sciences, National Center for Education Statistics, n.d.).

In addition to the lasting negative impact these closures are likely to have on children, they have been a major source of stress for parents (e.g. Lee et al. 2021) and potentially limit the ability of parents of young children to maintain or return to employment. These observations raise the question of whether ongoing school and daycare closures are a key driver of the slow labour market recovery in 2021.

As of June 2021, the US economy still had 7 million fewer jobs and an employment–population ratio lower by 2.6 percentage points than in February 2020 (US Bureau of Labor Statistics, n.d.). The labour-force participation rate remained 1.7 percentage points below its pre-pandemic level, even as other indicators, including record-high job openings and rapid wage growth, point towards tighter labour markets (Furman and Powell 2021).

Several factors have been proposed to explain the decline in labour supply, including ongoing concerns about contracting COVID-19 at work (Guilford 2021), expanded and enhanced unemployment insurance payments (Mutikani 2021), and childcare challenges facing working parents (Murray 2021). Understanding the relative importance of each of these factors is important to identify the types of policies that can help speed the labour market recovery.

In a recent paper (Furman et al. 2021), we quantify the potential importance of working parents with increased childcare burdens. We investigate how much of the aggregate decline in employment between the beginning of 2020 and the beginning of 2021 can be explained by excess job loss among parents, and particularly mothers, of young children.

This work complements and differs from existing papers investigating microlevel questions about whether and how employment outcomes are affected by school closures (e.g. Amuedo-Dorantes et al. 2020, Heggeness 2020, Sun and Russell 2021). It also builds on research showing that mothers have assumed greater childcare responsibilities than fathers during the pandemic (e.g. Bauer 2021).

It is possible that mothers have been especially burdened by childcare responsibilities during the pandemic, that in some instances school or daycare closures have led some parents to exit from work, and yet – as we find in our research – on an aggregate level, excessive employment declines among parents do not explain a sizeable share of ongoing job loss.

Employment declines among parents between Jan/Feb 2020 and Jan/Feb 2021

Data from the Bureau of Labor Statistics Current Population Survey reveals that between January/February 2020 (immediately before the COVID-19 pandemic hit the US) and January/February 2021, the employment–population ratio fell 5.0% among parents of young children (defined as younger than 13 years), with a 3.7% decline among fathers and a larger 6.3% decline among mothers. Among adults without young children, employment fell even more: 6.1% overall, with a larger decline among men and a slightly smaller decline among women. Lofton et al. (2021) find a similar pattern in their analysis of the labour market through December.

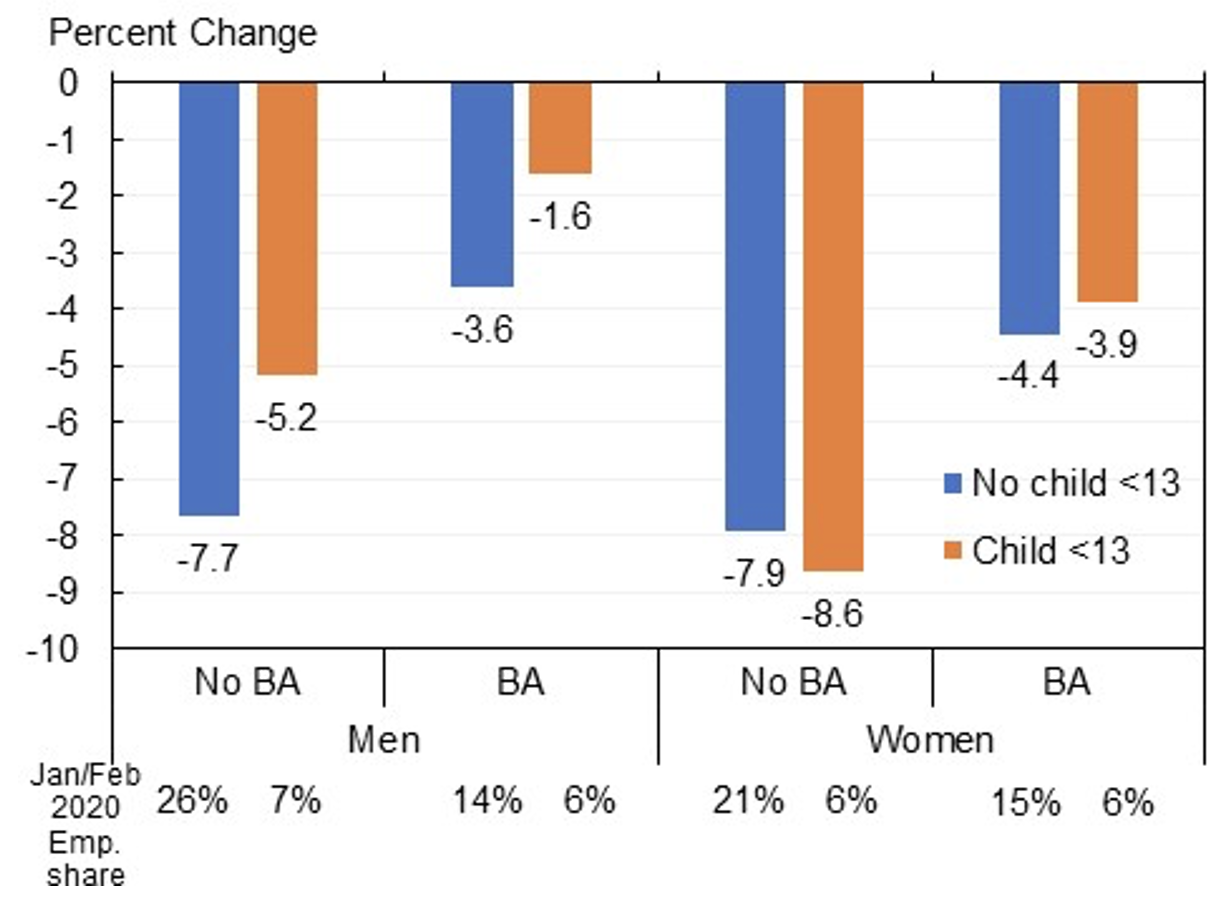

The relatively larger decline in employment among mothers of young children as compared with women without young children is driven by mothers without a bachelor’s degree, as shown in Figure 1. Among women without a bachelor’s degree, mothers with young children experienced an 8.6% employment decline, whereas women without a young child experienced a 7.9% decline.

Among women with a bachelor’s degree, employment fell by slightly less among mothers with young children (3.9%) than among other women (4.4%). As can be seen in Figure 1, among men, fathers of young children experienced smaller declines in employment than other men, among both education groups.

Figure 1 Percent change in employment-to-population rate between January/February 2020 and January/February 2021

Note: ‘Child’ refers to own child in the household, including adopted children and stepchildren. Percent of employed population as of January/February 2020.

Source: Furman et al. (2021).

What if parents of young children experienced the same employment declines as otherwise similar adults?

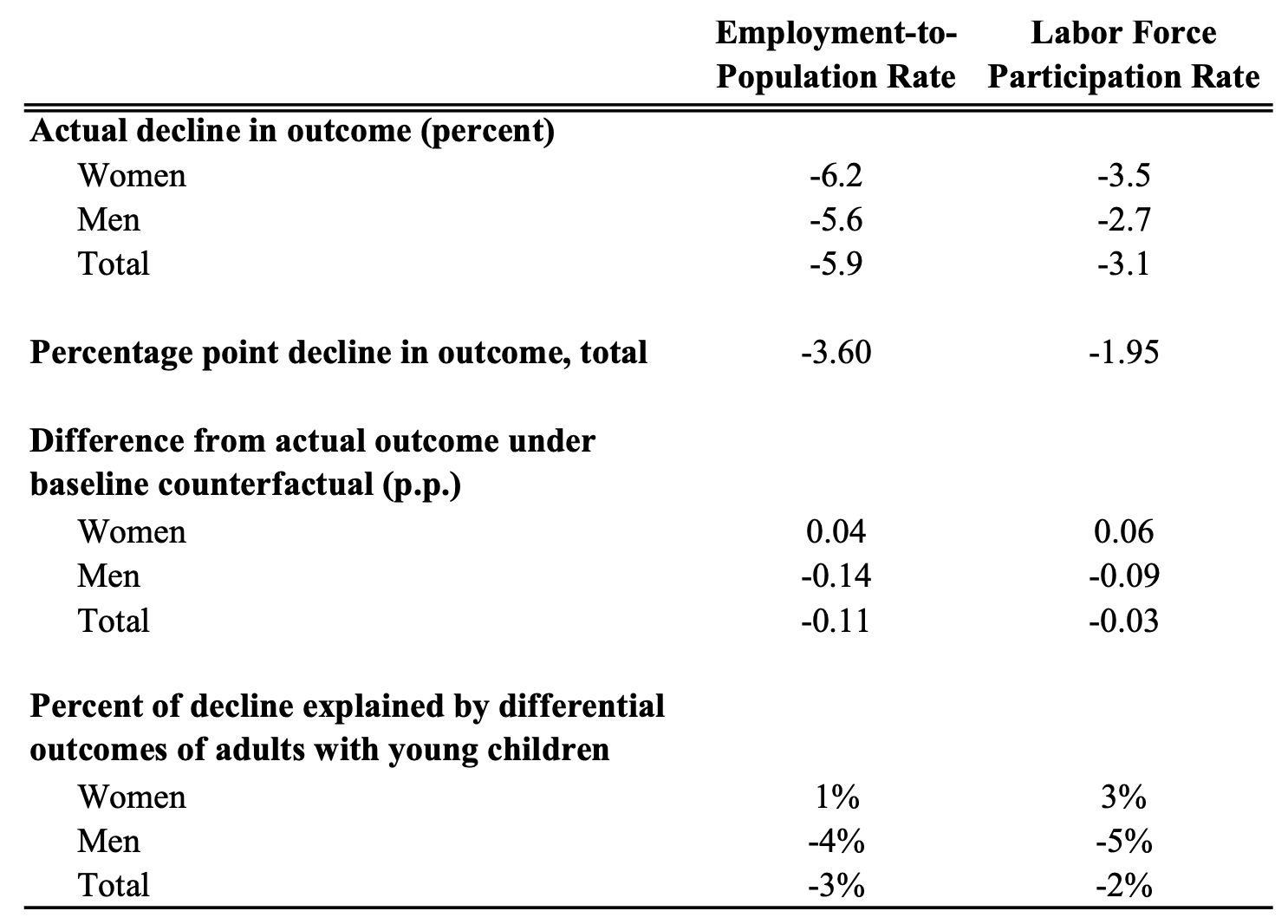

While mothers of young children, specifically those without a bachelor’s degree, experienced a larger decline in employment than other women during the pandemic, this alone is insufficient to assess how much of the 3.6-percentage-point decline in the employment–population ratio between 2020 and 2021 can be explained by excess employment loss among parents. We address this aggregate-level question with a counterfactual approach: we assign to parents of children under 13 the change in employment–population ratio and labour-force participation of otherwise similar adults without young children.

The results indicate that differential job loss among mothers of young children cannot explain a meaningful share of the total decline in employment between January/February of 2020 and 2021. Since fathers of young children experienced less of an employment decline than men without children, excess employment loss by parents of young children (mothers and fathers combined) cannot explain any of the total employment decline.

Our baseline results indicate that if parents of young children experienced the same change in employment as other adults in the same sex-age-education group, the decline in the employment–population ratio would have been larger by 0.11 percentage points, explaining 3% of the actual 3.6-percentage-point decline (see Table 1).

This is the result of opposite effects for mothers and fathers, with a 0.04-percentage-point (1%) smaller decline for mothers and a 0.14-percentage-point (4%) larger decline for fathers under the counterfactual. This counterfactual approach suggests similarly small changes in the labour force participation rate.

Table 1 Change in employment and labour force participation rates

Notes: p.p. = percentage point. Observed and simulated under counterfactual scenario assuming no disproportionate effect on adults with children under age 13, between January/February 2020 and January/February 2021. Under the baseline counterfactual, individuals with a child under age 13 are assigned the percent change in the employment rate or labour force participation rate as individuals without a child under age 13 within the same sex, educational attainment (bachelor’s degree vs. not), and age (16–24, 25–39, 40–54, 55+) group.

Source: Furman et al. (2021).

The results are robust to alternative definitions and comparison groups. Specifically, we alternatively define ‘young children’ to be under age 6 or under age 18. We also alternatively compare mothers of young children to men without young children, parents of young children to parents of teens, and parents of young children to adults with no children under 18. The findings are also not sensitive to the inclusion of additional controls, such as income, marital status, or race.

Conclusion

What explains the seemingly modest role of disproportionate employment declines among parents, and specifically mothers, in explaining the large decline in employment during the pandemic? First, declines in employment have been large for parents of young children and other adults alike. To the extent that mothers of young children experienced larger declines, these excess declines have been relatively modest.

Second, parents of young children are a relatively small share of employment, with mothers of young children accounting for 12% of employment in early 2020 and fathers of young children accounting for 13%. Thus, larger differences would be needed for differentially large declines in employment among parents to explain a substantial share of the aggregate decline.

Despite the burden placed on parents and children by school closures and ongoing challenges with childcare, these do not appear to be a meaningful factor in explaining the aggregate decline in employment in early 2021 relative to early 2020.

That parents of younger children did not disproportionately drop out of the labour force despite the added educational and childcare responsibilities is arguably a sign that safety nets were insufficient in the face of the COVID-19 pandemic, burdening these parents even more.

Nonetheless, it does suggest that policymakers seeking to speed the recovery of aggregate labour supply should consider the potential role of other factors, such as continued concern about COVID-19 or the expanded unemployment benefits, which have already expired in some states and are scheduled to expire nationally in early September.

References

Amuedo-Dorantes, C, M Marcén, M Morales and A Sevilla (2020), “COVID-19 school closures and parental labor supply in the United States”, IZA Discussion Paper Series 13827, October.

Bauer, L (2021), “Mothers are being left behind in the economic recovery from COVID-19”, Up Front, Brookings Institution, 6 May.

Furman, J, M S Kearney and W Powell III (2021), “The role of childcare challenges in the US jobs market recovery during the COVID-19 pandemic”, NBER Working Paper 28934 and PIIE Working Paper 21-8.

Furman, J, and W Powell III (2021), “Pace of US job growth picks up as signs point to tight labor market”, PIIE Realtime Economic Issues Watch, Peterson Institute for International Economics.

Guilford, G (2021), “The other reason the labor force is shrunken: Fear of COVID-19”, Wall Street Journal, 11 April.

Heggeness, M L (2020), “Estimating the immediate impact of the COVID-19 shock on parental attachment to the labor market and the double bind of mothers”, Review of Economics of the Household 18(4): 1053–78.

Lee, S J, K P Ward, O D Chang and K M Downing (2021), “Parenting activities and the transition to home-based education during the COVID-19 pandemic”, Children and Youth Services Review 122 (March).

Lofton, O, N Petrosky-Nadeau and L Seitelman (2021), “Parents in a pandemic labor market”, Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco Working Paper 2021-04 (February).

Murray, P (2021), “Sen. Patty Murray: That jobs report didn’t surprise working parents. It’s past time to make child care affordable for every family”, Ms. Magazine, 17 May.

Mutikani, L (2021), “US hiring takes big step back as businesses scramble for workers, raw materials”, Reuters, 7 May.

Sun, C, and L Russell (2021), “The impact of COVID-19 childcare closures and women’s labour supply”, VoxEU.org, 22 January.

US Bureau of Labor Statistics (n.d.), “Labor force statistics from the current population survey.”

US Department of Education, Institute of Education Sciences, National Center for Education Statistics (n.d.), “Monthly school survey”.