How has immigration over the past decades affected economic inequality in the UK? Have inflows widened or compressed the UK wage distribution through competition with British-born workers? Does the presence of immigrants itself change the composition of the UK workforce in a way that alters wage inequality? In a recent paper (Dustmann et al. 2023), we address these questions.

There are two main ways through which immigration can affect wage inequality. The first is by directly affecting the wages of native workers (e.g. Portes 2018, Monras 2019). The second is by changing the composition of the workforce (e.g. Slacalek et al. 2022). In this column, we quantify these effects.

Immigration to the UK over the last 40 years

The share of foreign-born in the UK rose from 5.3% in 1975 to 13.4% in 2015. During this period, the UK experienced a large increase in the share of immigrants and a pronounced change in their origin. While immigration to the UK was driven in the earlier years of this period by individuals from non-EU countries, the share of those born in the EU, particularly the A8 countries, sharply increased from 2004 onwards. After the Brexit referendum in 2016, net migration from the EU fell back.

Immigrants to the UK over the past 40 years have been consistently better educated than the British-born workforce. Despite their higher educational attainments, immigrants do not work in jobs waged commensurately to these achievements. Upon their arrival in the UK, they tend to work in occupations that are in substantially lower earnings categories than those to which they would be allocated if their education were rewarded similarly to British-born workers (Dustmann et al. 2013). Moreover, most migrations are temporary (e.g. Dustmann and Görlach 2016a, 2016b, Adda et al. 2022, Jones 2019). Among immigrants who arrived in the UK between 2005 and 2015, the share of an arrival cohort still in the country five years after arrival was around 75% for non-EU nationals and 60% for EU nationals.

The impact on the wage distribution of British-born workers

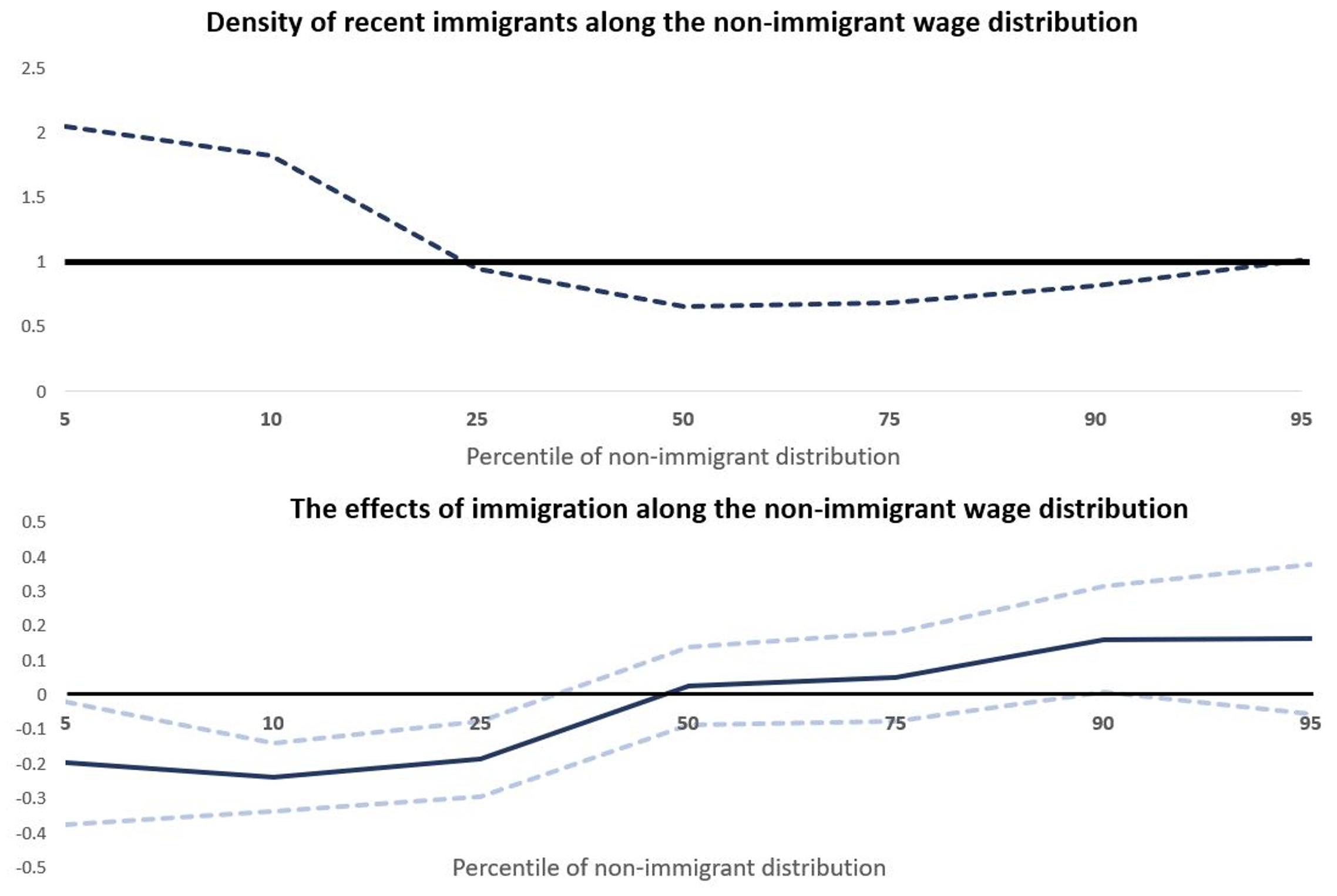

The bottom panel of Figure 1 presents estimates of the effect of immigration at points along the distribution of wages for British-born workers from the 5th percentile to the 95th percentile, showing the estimated percentage point effect of an immigrant inflow equal to 1% of the non-immigrant population. The top panel shows where immigrants are found in that distribution, plotting estimates of the relative concentration of newly arrived immigrants along the same distribution. Where the dashed line lies above one, recent immigrants are estimated to be more concentrated than British-born workers, and where it is below one, they are less so. The methodology draws on Dustmann et al. (2013), and we have updated the time window from 2005 to 2016.

Figure 1

Note: The top panel illustrates the estimated concentration of immigrants who arrived within the last 2 years along the distribution of wages for non-immigrant workers in the UK. The bottom panel shows the estimated effects of an immigrant inflow equal to 1% of the non-immigrant population along the same distribution. The short-dashed lines in the bottom graph illustrate 5% confidence intervals. Source: UK LFS 1994- 2016

The figure shows that immigration has put a slight downward pressure on non-immigrant wages at the bottom of the wage distribution, precisely where recently arrived immigrants are estimated to be more concentrated than British-born workers. Non-immigrant wages at higher percentiles of the distribution, where the concentration of immigrants is lower relative to the British-born, appear to benefit slightly. Over the study period, the estimates suggest that immigration held back real hourly wages by 0.47p and 0.64p per year at the 5th and the 10th percentile, respectively, while it added 1.68p per year to real hourly wages at the 90th percentile of the native distribution.

The impact on the composition of the workforce

Besides changing the distribution of native wages, immigration can also change the overall earnings distribution by changing the composition of the population, even if British-born workers’ wages are unchanged. They can do this either because there is inequality between immigrant and non-immigrant workers or because the inequality within the immigrant community is greater or less than in the native population. To distinguish these effects, it is useful to measure inequality in a way that allows decomposition into between- and within-group components. We choose, therefore, to present estimates using a common measure – the Theil index – that can be decomposed in this way.

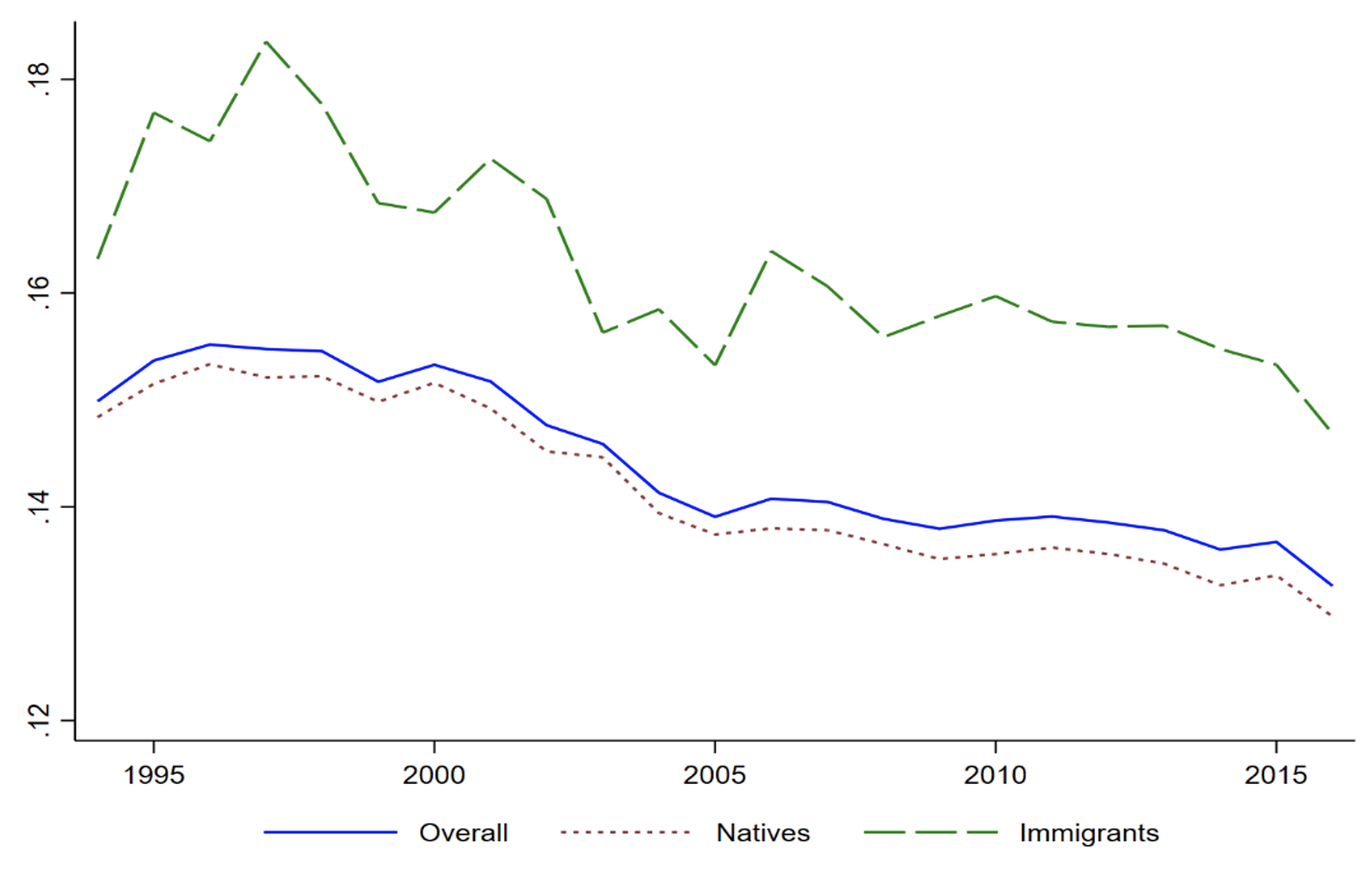

Figure 2 plots the evolution of the Theil index measuring wage inequality in the UK from 1994 to 2016, decomposing overall inequality (solid blue line) into inequality within the British-born group (dotted red line) and inequality within the immigrant group (dashed green line). The solid blue line is a weighted average of the red and green lines plus the index for inequality between immigrants and non-immigrants (which, in our case, is very small and omitted from the graph).

Figure 2

Note: The figure illustrates the evolution of the Theil index measuring overall wage inequality, within-group wage inequality for non-immigrants and within-group wage inequality for immigrants. Overall wage inequality is decomposed into within-group inequality for non-immigrants, within-group inequality for immigrants and inequality between these two groups. Between-group inequality is omitted since it is close to zero. Hourly wages are deflated at 2015 prices (conditional on employment) and we trim the bottom and top 1% of the sample to exclude outliers. Source: UK LFS 1994-2016

The figure shows that overall wage inequality is consistently decreasing from 2000 onwards. Average immigrant and non-immigrant wages are so close that between-group inequality is unimportant. However, wage inequality among British-born workers is consistently substantially lower than among the immigrant group, so the compositional effect of including immigrants in the population raises inequality. The total magnitude of the compositional effect is the difference between the solid blue and dotted red lines.

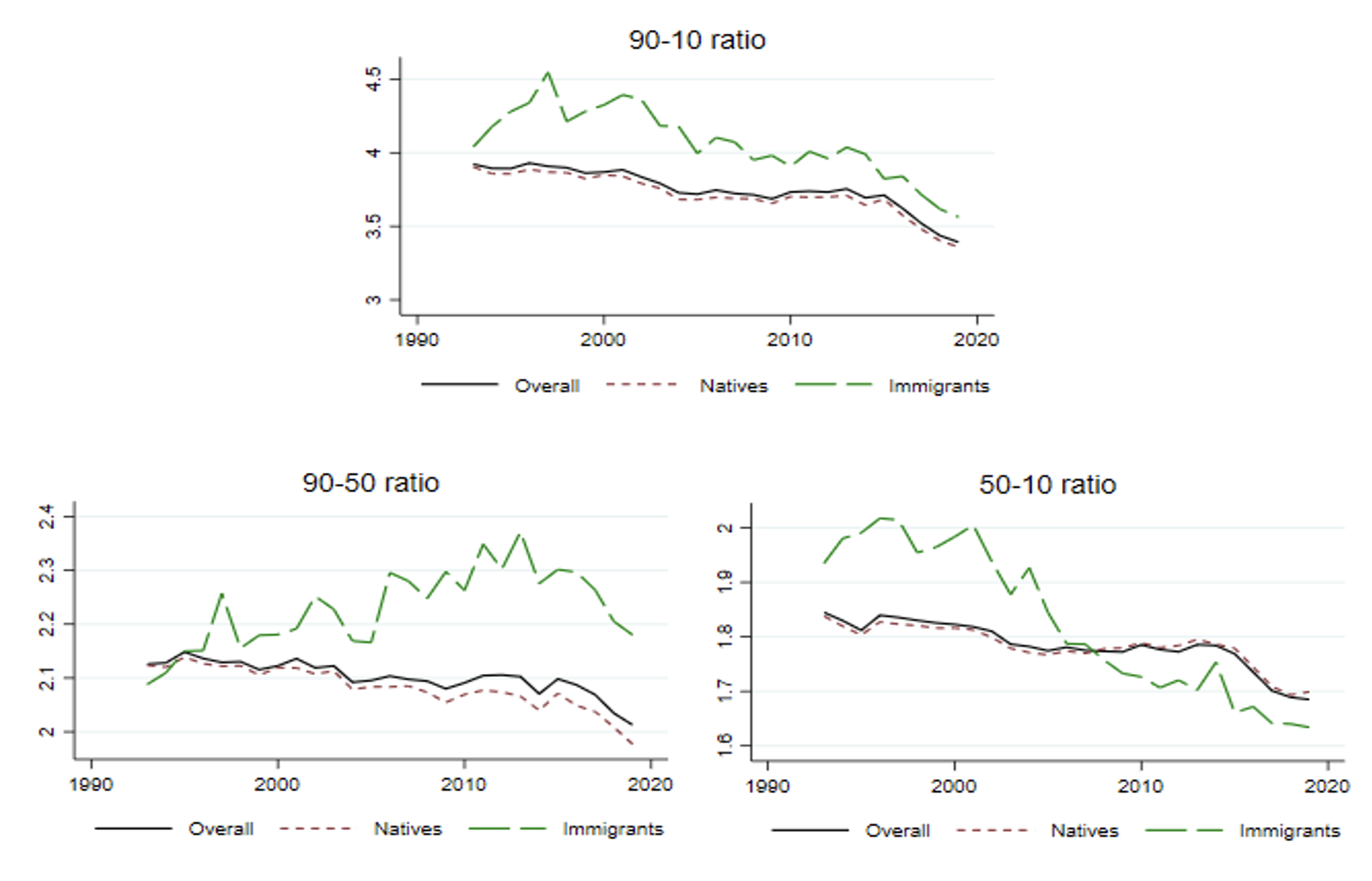

To help understand this, we consider wages within each group at specific points in their distributions. In particular, Figure 3 looks at ratios between wages at the 90th percentile, median and 10th percentile within the immigrant and non-immigrant populations. For British-born workers, inequality decreased both above and below the median. In contrast, for immigrants, the 90-50 ratio first increased (until about 2012) and then decreased, while the 50-10 ratio decreased since 2000. Thus, the overall decrease in wage inequality among immigrants was driven by a significant reduction of wage inequality at the bottom half of the wage distribution, which overcompensates for the increase in wage inequality in the top half.

The reduction in wage inequality at the bottom half of the immigrant distribution is driven by a persistent increase in the wage at the 10th percentile starting towards the end of the 1990s, a trend also observed for wages at the 10th percentile of the non-immigrant distribution. This is likely driven by rises in the minimum wage during this period (see Lindley and Machin 2013, who illustrate that the National Minimum Wage grew faster than average earnings in the UK from 1999-2010).

Figure 3

Note: The figure illustrates the evolution of percentile ratios of hourly wages for non-immigrant and immigrant groups in the UK. Hourly wages are deflated at 2015 prices (conditional on employment) and we trim the bottom and top 1% of the sample to exclude outliers. Source: UK LFS 1994-2016

Discussion

Our findings illustrate that the overall effect of immigration on wage inequality in the UK has been limited. Neither it’s effect on the distribution of wages through inducing changes in the price of labour nor its effect through affecting the composition of the wage-earning population has been at all sizeable. Even though immigration slightly stretches the wage distribution of British-born workers by decreasing wages at the bottom and increasing wages at the top, the magnitudes of these effects are small. Wage inequality among immigrants is higher than among non-immigrants, and including immigrants in the population raises overall wage inequality. Nevertheless, the low number of immigrants relative to the native population makes the compositional effect on the overall earnings distribution small.

References

Adda, J, C Dustmann and J-S Görlach (2022), “The Dynamics of Return Migration, Human Capital Accumulation, and Wage Assimilation”, The Review of Economic Studies 89(6): 2841-2871.

Dustmann, C and J-S Görlach (2016a), “The Economics of Temporary Migrations”, Journal of Economic Literature 54(1): 98–136.

Dustmann, C and J-S Görlach (2016b), “Estimating immigrant earnings profiles when migrations are temporary”, Labour Economics 41: 1–8.

Dustmann, C, T Frattini and I P Preston (2013), “The Effect of Immigration along the Distribution of Wages”, The Review of Economic Studies 80(1): 145–173.

Dustmann, C, Y Kastis and I Preston (2023), “Inequality and immigration”, CReAM Discussion Paper No. 0723.

Jones, M (2019), “Immigrants’ earnings growth and return migration from the US”, VoxEU.org, 25 April.

Lindley, J and S Machin (2013), “Wage inequality in the Labour years”, Oxford Review of Economic Policy 29(1): 165–177.

Monras, J (2019), “Immigration and wage dynamics: Evidence from the Mexican peso crisis”, VoxEU.org, 3 March.

Portes, J (2018), “The economic impacts of immigration to the UK”, VoxEU.org, 6 April.

Slacalek, J, J Perez, A Kolndrekaj, M Propst and M Dossche (2022), “Immigrants and the distribution of income and wealth in the euro area”, VoxEU.org, 15 October.