The EU economy has had to grapple with unprecedented shocks in the past four years…

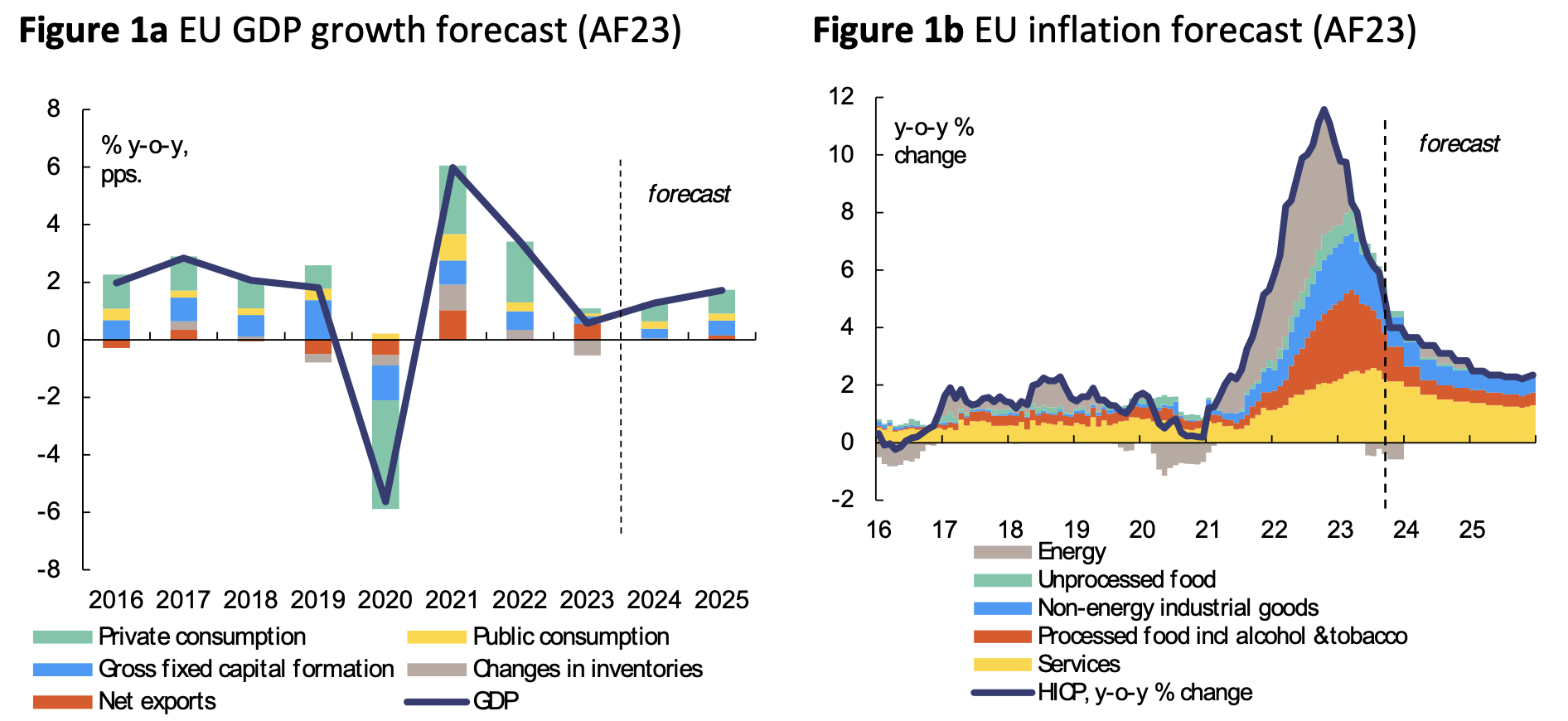

In close succession, the COVID-19 pandemic, global supply side shortages, the war in Ukraine and the related energy crisis, and surging inflation have battered the EU economy. Overall, the EU economy has stood up well to these formidable shocks, and, until last year, surprisingly well (Verwey et al. 2023). However, following a vigorous rebound in 2021 and 2022, the EU economy has lost momentum this year, and more than previously expected. The terms-of-trade improvement that started unfolding in late 2022, thanks to the steep decline in energy prices, was stronger than expected last spring, but failed to keep the EU economy in motion. Still high, though declining, inflation and tightening financing conditions took a heavy toll, depressing confidence and weighing on consumption and residential investment. The slump in global trade deprived our economies of the needed external support. As a result, the EU economy barely grew in the first three quarters of 2023. The European Commission Autumn Forecast (European Commission 2023a) projects GDP growth in 2023 at 0.6% in both the EU and the euro area.

…but remaining elements of resilience should help ensure a gradual resumption of growth, amid continued decline in inflation

Growth is expected to rebound mildly as consumption recovers with rising real wages, investment remains supportive and external demand picks up. EU GDP growth is forecast to improve to 1.3% in 2024 and gain further pace, to 1.7%, in 2025.

HICP inflation has reached a two-year low in the euro area in October and is projected to continue declining over the forecast horizon, though at a more moderate pace than in the past year, reflecting easing of inflationary pressures in food, manufactured goods and services. In the EU, it is set to decrease from 6.5% in 2023 to 3.5% in 2024 and 2.4% in 2025.

The strength of the EU labour market is the main force behind the outlook. The EU labour market continued to perform strongly in the first half of 2023, despite the slowdown in economic growth. Activity and employment rates reached their highest level on record, and in September the unemployment rate remained close to its record low. Data published after the cut-off date of the forecast show that job creation continued also in the third quarter. Despite some signs of weakening, it is set to be a key driving force of the rebound. Moreover, nominal wage growth is set to catch up with a lag and exceed inflation in 2024 and 2025, finally allowing workers to recoup purchasing power. This is compatible with inflation coming back to target as labour productivity increases and unit profits decline.

Strong corporate balance sheets are another element of resilience for the EU economy. Despite tight financing conditions, they provide room for addressing the business transformation and capacity adjustment needed for the transition to energy saving and low-emission production. Full implementation of the reforms and investments under the Recovery and Resilience Facility (RRF) is also set to support the green and digital transitions, as well as infrastructure investment.

Uncertainty and downside risks to the economic outlook have increased in recent months. They are primarily related to the evolution of Russia’s protracted war against Ukraine and the conflict in the Middle East. Energy markets appear most vulnerable, as renewed disruptions to energy supplies could have a significant impact on energy prices, output, and inflation. The transmission of monetary tightening may weigh on economic activity for longer and to a larger degree than projected in this forecast.

The persistent tightness of the labour market seems to be driven by strong labour demand rather than falling labour supply or mismatches

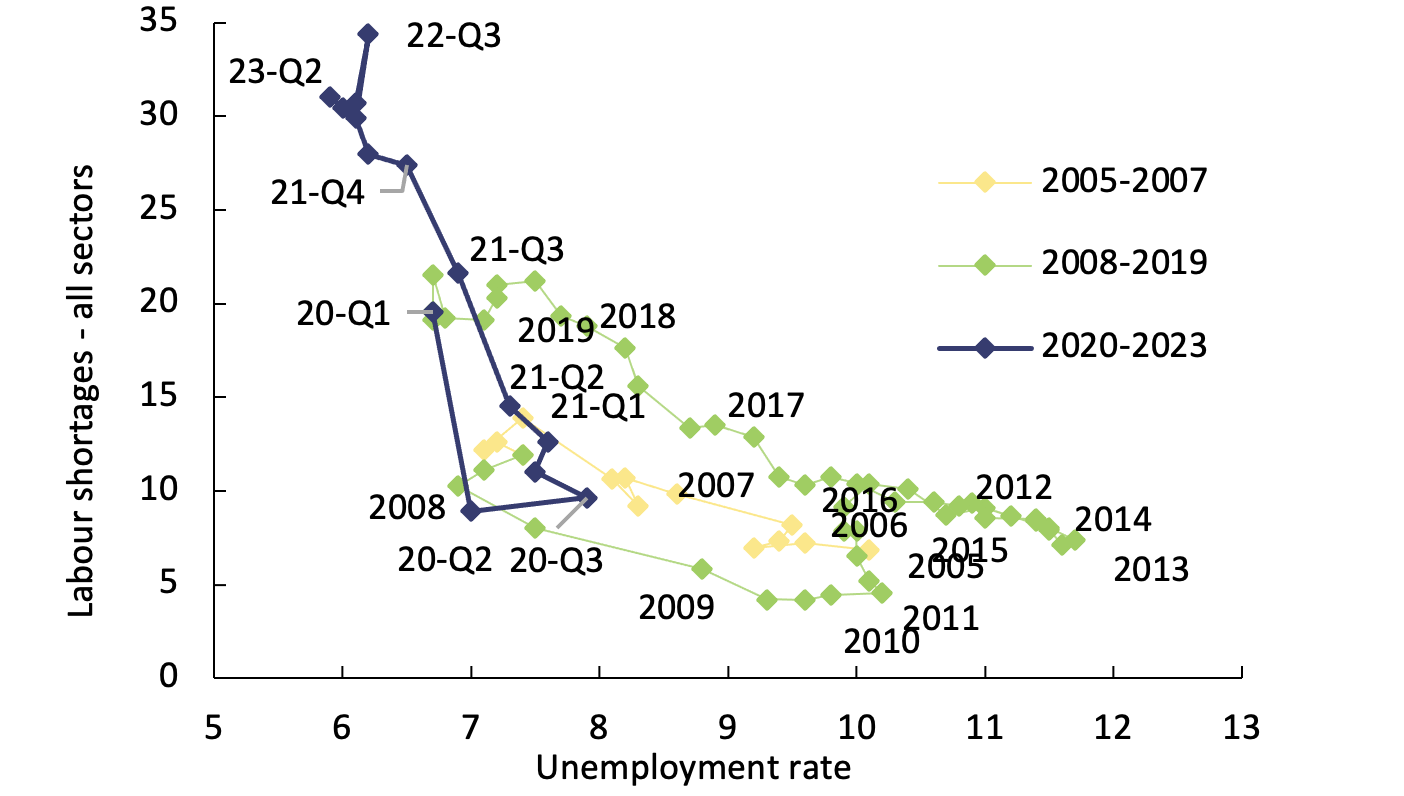

In the past year, EU labour markets remained tight despite the ongoing economic slowdown. While the surge in labour shortages observed in the aftermath of the pandemic is easily interpreted as the result of the sudden reopening of the economy (e.g. Turrini et al. 2022), the persistence of low unemployment and high rates of vacancies and labour shortages calls for a reappraisal of the drivers of labour market tightness in the EU. Potential explanations of the labour market tightness are an increase in labour market mismatches at the macroeconomic level, falling labour supply, growing labour demand, or a combination of factors.

Labour market mismatches have played only a marginal role in driving labour market tightness. Job vacancies and unemployment have largely returned to their long-term negatively sloped relationship (the ‘Beveridge curve’) after a counter-clockwise movement in the unemployment-vacancy space at the onset of the pandemic (Figure 2).

This suggests that matching efficiency has not deteriorated. Moreover, also other indicators of labour market mismatches are close to their record low levels.In particular, such indicators include that of sectoral mismatch measured as the dispersion of reported labour shortages across industry, services and construction, and the macroeconomic skills mismatch indicator measured as the relative dispersion of employment rates by educational levels.

Figure 2 EU Beveridge curve, 2005-2023

Notes: The vacancy rate has been proxied by the share of firms in industry, services and construction indicating that labour is a “factor limiting production” in the European Business and Consumer Survey.

Source: European Commission calculations based on Eurostat (EU Labour Force Survey) and European Business and Consumer Survey.

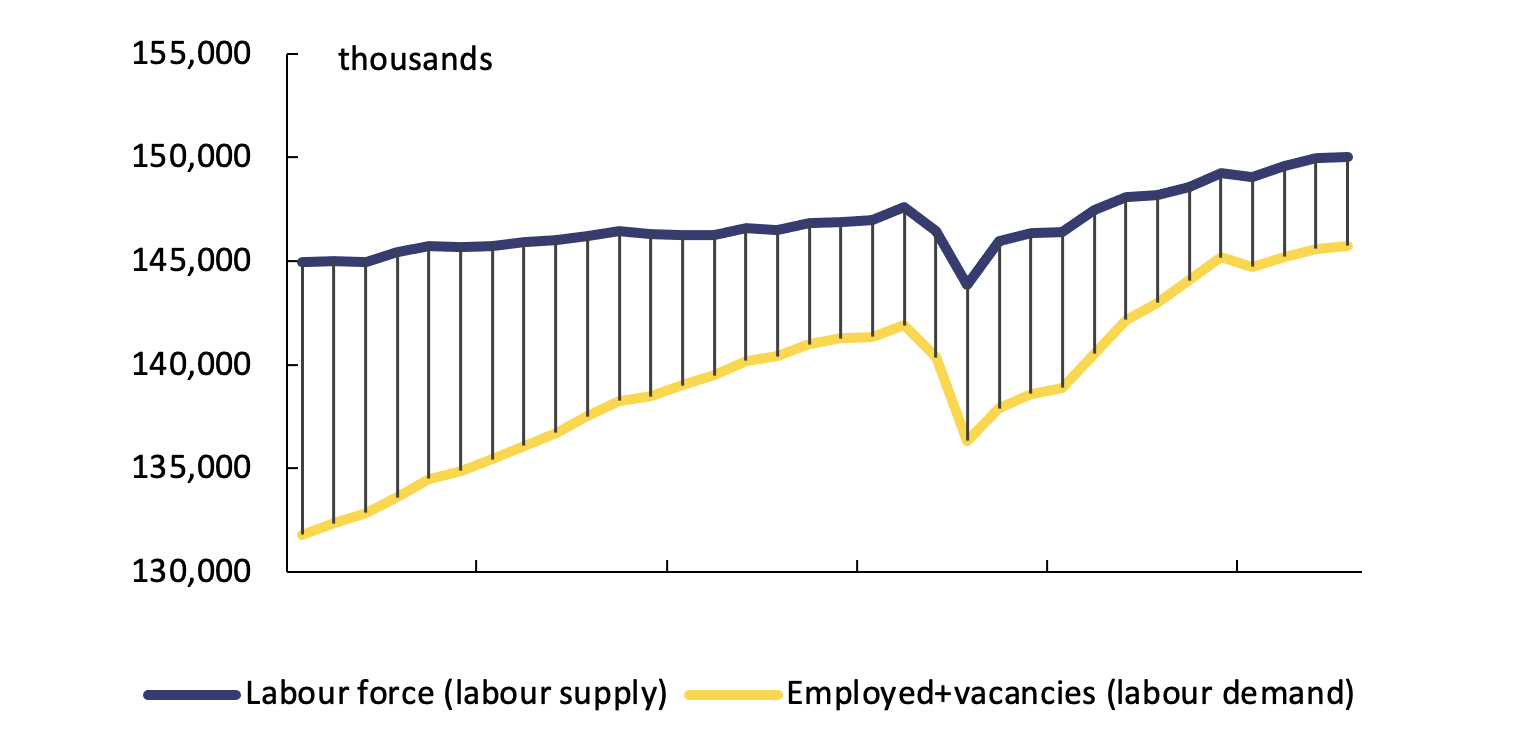

The post-pandemic tightening of the labour market seems associated with growing labour demand rather than falling labour supply. The drop in participation rates that contributed to labour market tightening in the US did not materialise in the EU. On the contrary, after the COVID crisis, the number of persons active on the labour market swiftly recovered and, in the second quarter of 2023, the EU labour force exceeded its pre-pandemic level by more than 1%. However, growth in labour demand was likely even stronger, as suggested by a proxy consisting of the sum of employed persons and vacancies (Figure 3).

Figure 3 Labour demand and supply in the EU, 2015Q1-2023Q2 (thousands of individuals)

Note: Labour supply is proxied by the active population, labour demand by the sum of employed and vacancies.

Source: European Commission based on Eurostat (EU Labour Force Survey and Job Vacancy Survey excluding DK, FR, IT and MT (due to data limitations)).

Falling real wages after COVID-19 may have contributed to sustained labour demand (Gourinchas 2023). Real wages fell in the aftermath of the inflationary shock which started in 2021, lagging behind productivity growth. Alongside the decline in real wages, profit shares surged in the post-pandemic period to high levels.

Additional factors may have played a role in keeping vacancies at historical high levels despite decelerating economic activity. First, firms may have become more reluctant to lay off workers as, in a context of high labour shortages, re-hiring workers may be difficult. This phenomenon of ‘labour hoarding’ may be reflected in the fall in separation rates. Second, part of the new vacancies could reflect the medium-term need to restructure the skill portfolio rather than the immediate need of hiring to be able to meet current demand. The prospect of facing larger replacement needs in the coming years may have triggered part of the increase in vacancies already in the present. Third, posting vacancies may have become cheaper (e.g. online posting and interviews). This may have led some firms to post vacancies in order to have the option to hire high-profile talents among a pool of potential applicants.

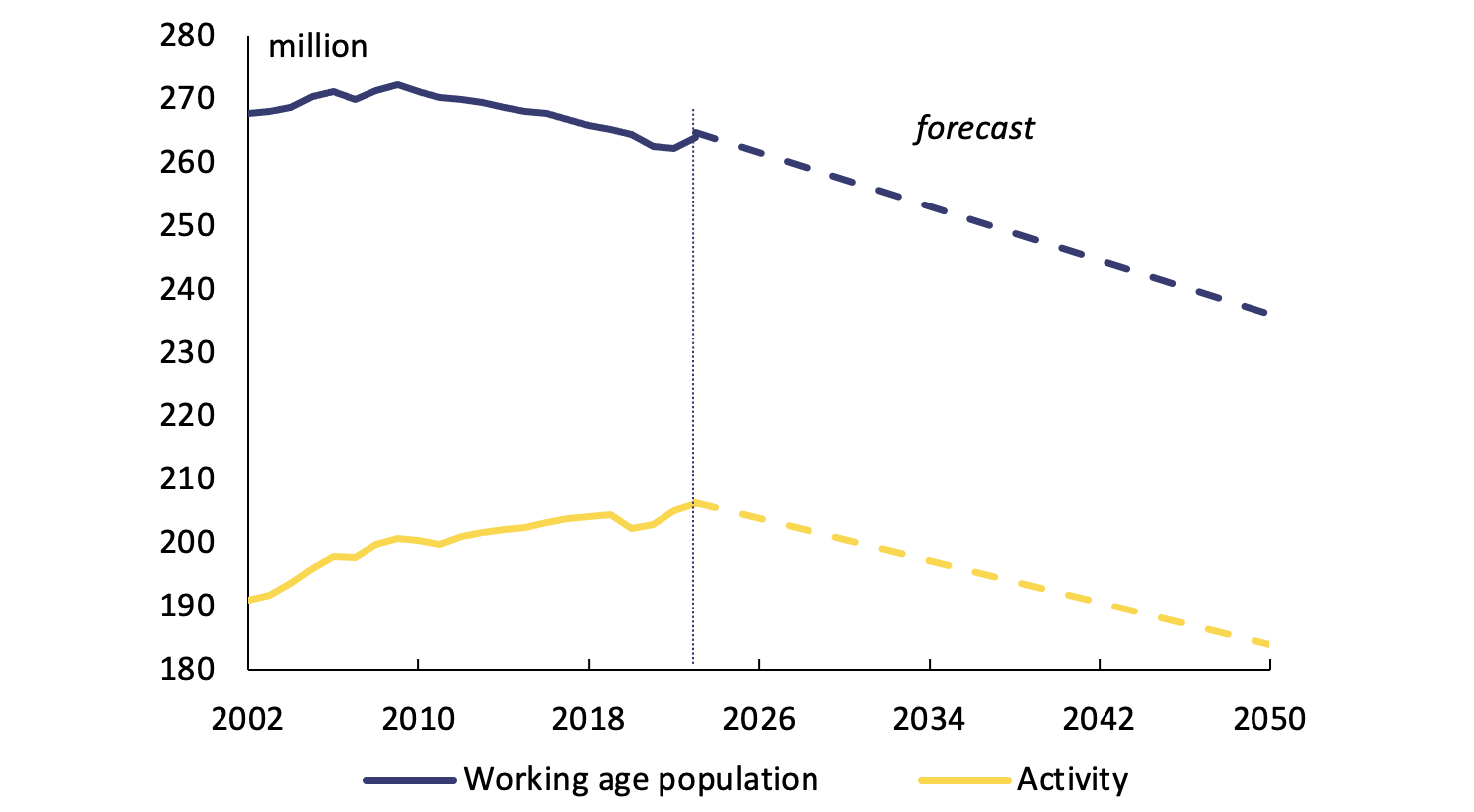

Going forward, the economic slowdown and reduced corporate profits are likely to contribute to reduce labour market shortages, while structural drivers of labour supply will continue to contribute to labour market tightness. The long-term declining trend in average hours worked is expected to continue to curb effective labour supply (Arce et al. 2023). At the same time, population ageing is expected to further reduce the size of the labour force, due to an overall decline in the working-age population and an increasing larger share of older workers, which have on average a lower labour market participation rate than prime-age workers (Figure 4) (European Commission 2023b).

Figure 4 Changes in EU working age population and active populations, 2002-2050 (in millions)

Source: European Commission (2023): “Employment and Social Developments in Europe”, Directorate-General for Employment, Social Affairs and Inclusion.

Social and economic aspects to be addressed by active policies

Despite the good performance of the labour market, some groups are still under-represented – for example, women, youth, low-skilled, and persons with disabilities. Active labour market policies play a key role in boosting participation, with positive economic effects in the long-term. Promoting upskilling and reskilling are also crucial to address shortages. As low-income households suffered most from the rise in the cost of living mainly related to the energy crisis and the associated worsening in the terms of trade, wage developments, in compliance with national practices and in respect of social partners, should aim at mitigating losses in purchasing power especially for these groups. They should also reflect competitiveness dynamics, avoiding lasting divergences within the Union.

References

Arce, O, A Consolo, A Dias Da Silva and M Mohr (2023), “More jobs but fewer hours”, ECB Blog, 7 June.

Arpaia, A and A Halasz (2023), “Short- and long-run determinants of labour shortages”, Quarterly Report on the Euro Area 22(1).

Duval, R, Y Ji, L Li, M Oikonomou, C Pizzinelli, I Shibata, A Sozzi and M M Tavares (2022), “Labor Market Tightness in Advanced Economies”, Staff Discussion Notes No. 2022/001.

European Commission (2022), “Labour market and wage developments in Europe: Annual Review 2022”, Directorate-General for Employment, Social Affairs and Inclusion.

European Commission (2023a), European Economic Autumn 2023 Forecast, European Economy Institutional Paper 258, DG ECFIN, November.

European Commission (2023b), “Employment and Social Developments in Europe. Annual Review 2023”, Directorate-General for Employment, Social Affairs and Inclusion.

Gourinchas, P-O (2023), “Global Economy on Track but Not Yet Out of the Woods”, IMF Blog, 25 July.

Kiss, A, M C Morandini, A Turrini, and A Vandeplas (2022), “Slack and Tightness: Making Sense of Post COVID-19 Labour Market Developments in the EU”, European Commission (DG ECFIN), Discussion Paper 178.

Soldani, E, O Causa, N Luu and M Abendschein (2022), “The post-COVID rise in labour shortages across OECD countries”, VoxEU.org, 28 November.

Turrini, A, A Vandeplas and A Kiss (2022), “Tight euro area labour markets after Covid-19: The role of labour market mismatch”, VoxEU.org, 19 August.

Verwey, M, A Monks and K Orsini (2023), “Winter resilience lifts outlook for EU growth amid persistent challenges”, VoxEU.org, 22 May.