The euro area economy is slated for a soft landing, but it is not out of the danger zone. Since its peak in autumn 2022, headline inflation has declined steadily on the back of falling energy inflation, the rapid rise of interest rates, and the orderly tightening of financial conditions (IMF 2023). At 2.2%, euro area inflation is projected to be back close to target by 2025, according to the European Commission’s Autumn Forecast

(European Commission 2023a). At the same time, employment remains strong, and financial markets absorbed the reversal of interest rates without much disruption. So far, so good!

Yet, the growth momentum weakened at the turn of the year, core inflation is still elevated, and inflation differentials remain across euro area Member States. It is therefore too early to claim victory. In particular, higher energy prices and rising unit labour costs continue to put export competitiveness under pressure and call for policy attention.

Furthermore, old and new structural forces weigh on competitiveness and productivity growth going forward. In addition to demographic change and a high level of legacy debt, weak investment and innovation, the imperative green transition, and a fragmenting geopolitical landscape are posing threats to productivity and potential growth. In line with the latest recommendations to the euro area (European Commission 2023b), we argue that, in the short term, careful policy coordination is needed to support the smooth disinflation under way and to keep in place the conditions for a gradual recovery of the euro area economy.

At the same time, more investment and innovation are essential to spur long-term growth and enhance productivity and competitiveness in the ongoing green transition. Substantial supply-side reforms and deeper euro area integration are critical in that respect. In particular, a deeper Single Market and progress towards a Capital Market Union hold huge potential for the euro area economy.

Careful policy coordination to ensure continued disinflation and recovery of competitiveness in the short term

Ensuring the return of inflation to the European Central Bank’s target remains an immediate priority. Continuing to ensure a consistent monetary and fiscal policy mix is critical. Consistent with the new set of fiscal rules agreed by EU economy and finance ministers on 20 December 2023, public debt should be kept at prudent levels or put on a downward trend. At the same time, fiscal policy should contribute to disinflation. In this vein, delivery on the overall restrictive fiscal stance as envisaged in the 2024 budget plans will be important. Phasing out energy support measures adopted in light of the energy price shock of 2022 will support fiscal consolidation efforts. To avoid lasting divergences across the euro area, these efforts should be more ambitious in countries that face higher risks of entrenched inflationary pressures.

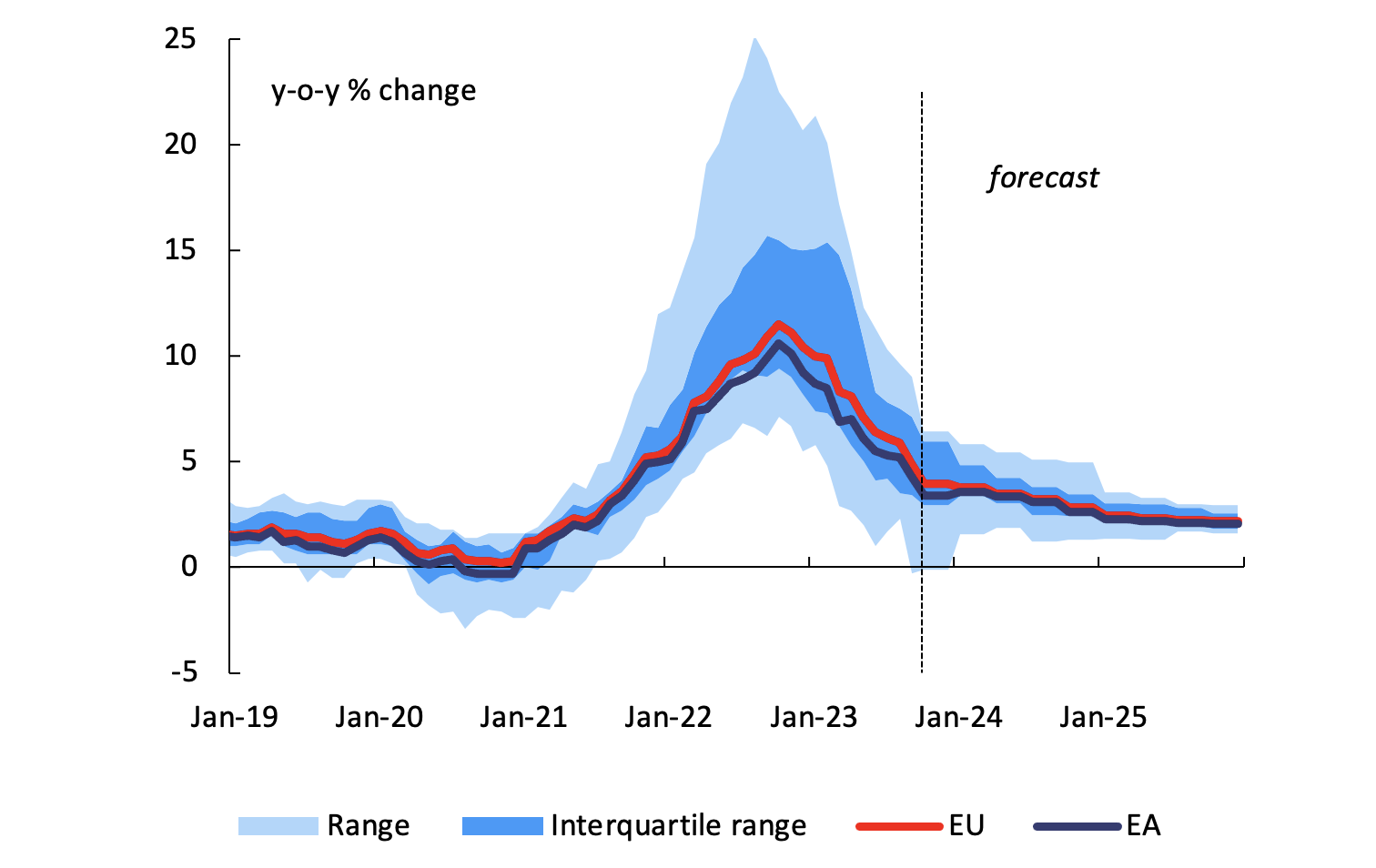

Differences in inflation across euro area countries declined but remain sizeable (Figure 1), contributing to concerns about cost competitiveness vis-à-vis intra- and extra-euro area trading partners. Differences in the energy intensity of the economies explain most of the country-specific impact of the 2022 common energy price shock on inflation (Coutinho and Licchetta 2023). Although energy prices receded, divergences in core inflation and unit labour costs remain a concern. Unit labour cost accelerated strongly in 2023, especially in the Baltics and Slovakia, on the back of significant nominal wage increases and stagnant or falling productivity growth. At the other end of the spectrum, unit labour cost growth was contained in Greece, Italy, and Spain, where it helped re-balance pre-existing weaknesses in cost competitiveness.

Going forward, the relative evolution of unit labour costs will become increasingly important to ensure that today’s relative cost disadvantages do not become entrenched. In accordance with national practices and respecting the role of social partners, it is therefore important that further wage increases continue to restore lost purchasing power, especially for low-income earners, taking account of the underlying competitiveness dynamics.

Figure 1 Range of annual harmonised index of consumer price inflation rates among EU Member States

Source: Eurostat.

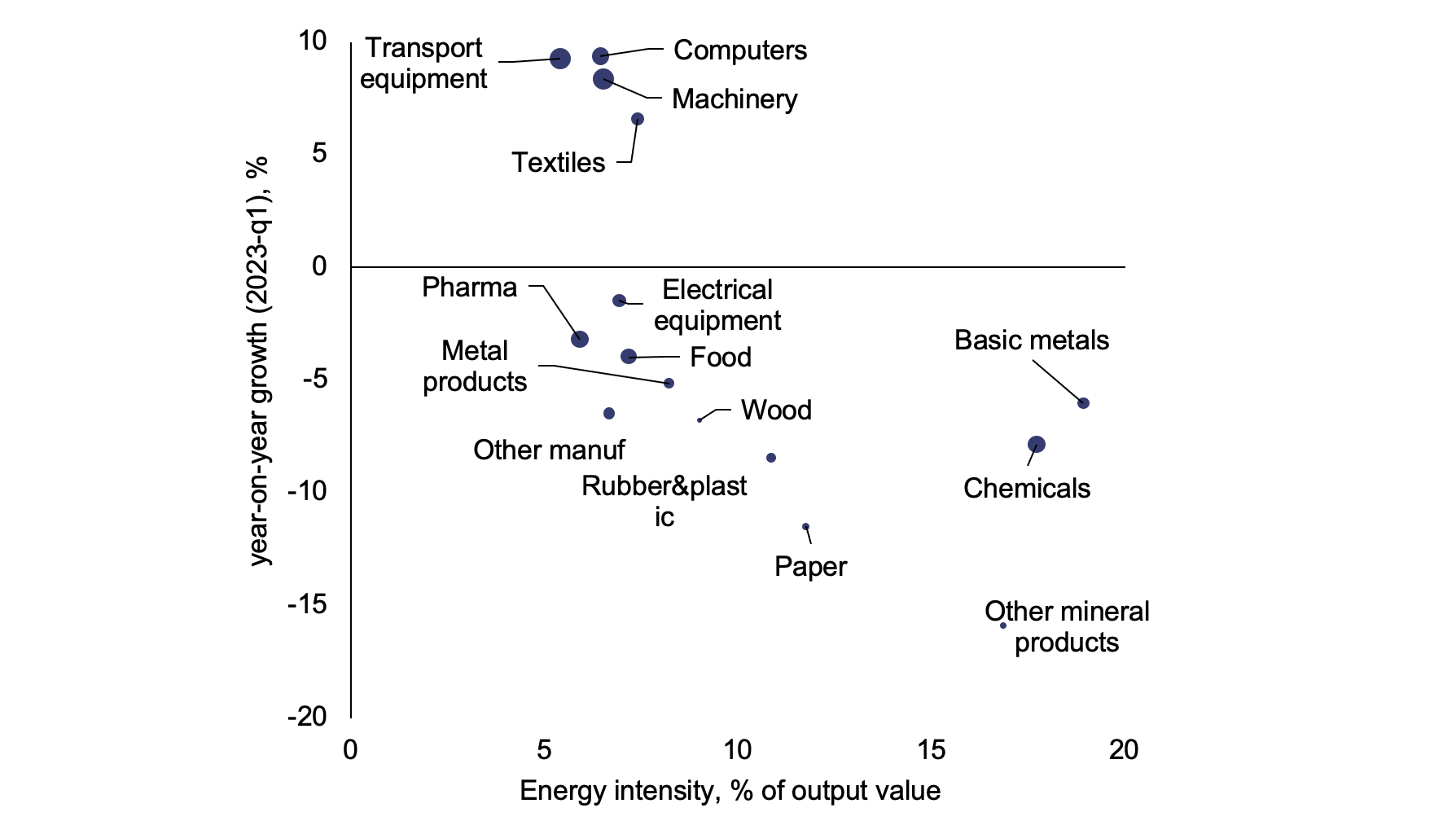

Figure 2 Energy intensity and euro area export growth by sector

Source: Eurostat.

More investment and innovation are needed to strengthen competitiveness

Addressing the structural impediments to competitiveness and growth in a durable way requires a broad set of supply-side policies. Let’s start with energy. Energy prices have come down considerably compared to their peak but are expected to stay structurally higher than before Russia invaded Ukraine. Until major progress is made in renewables, energy will remain considerably more expensive in the euro area than in the US and many other trading partners. The relative depreciation of the euro in 2021 and 2022 provided only a temporary respite. It is therefore not surprising that energy-intensive sectors, such as chemicals, have seen their trade performance deteriorate (Figure 2) and euro area companies more broadly rate their competitiveness at an all-time low (European Commission 2023c).

Beyond the recent increase in energy prices, the euro area suffers from a protracted weakening of productivity growth and lack of innovation. Total factor productivity in the euro area has been trailing that of the US economy for many years. More concerning, productivity has been floundering in sectors that are driving aggregate growth, including most notably in the ICT sector (manufacturing of computers and electronics, IT services). While the decline of the euro area’s active population makes labour-augmenting technological progress all the more important, innovation – measured both through the size of the research efforts or through its output in terms of patents – remains weak.

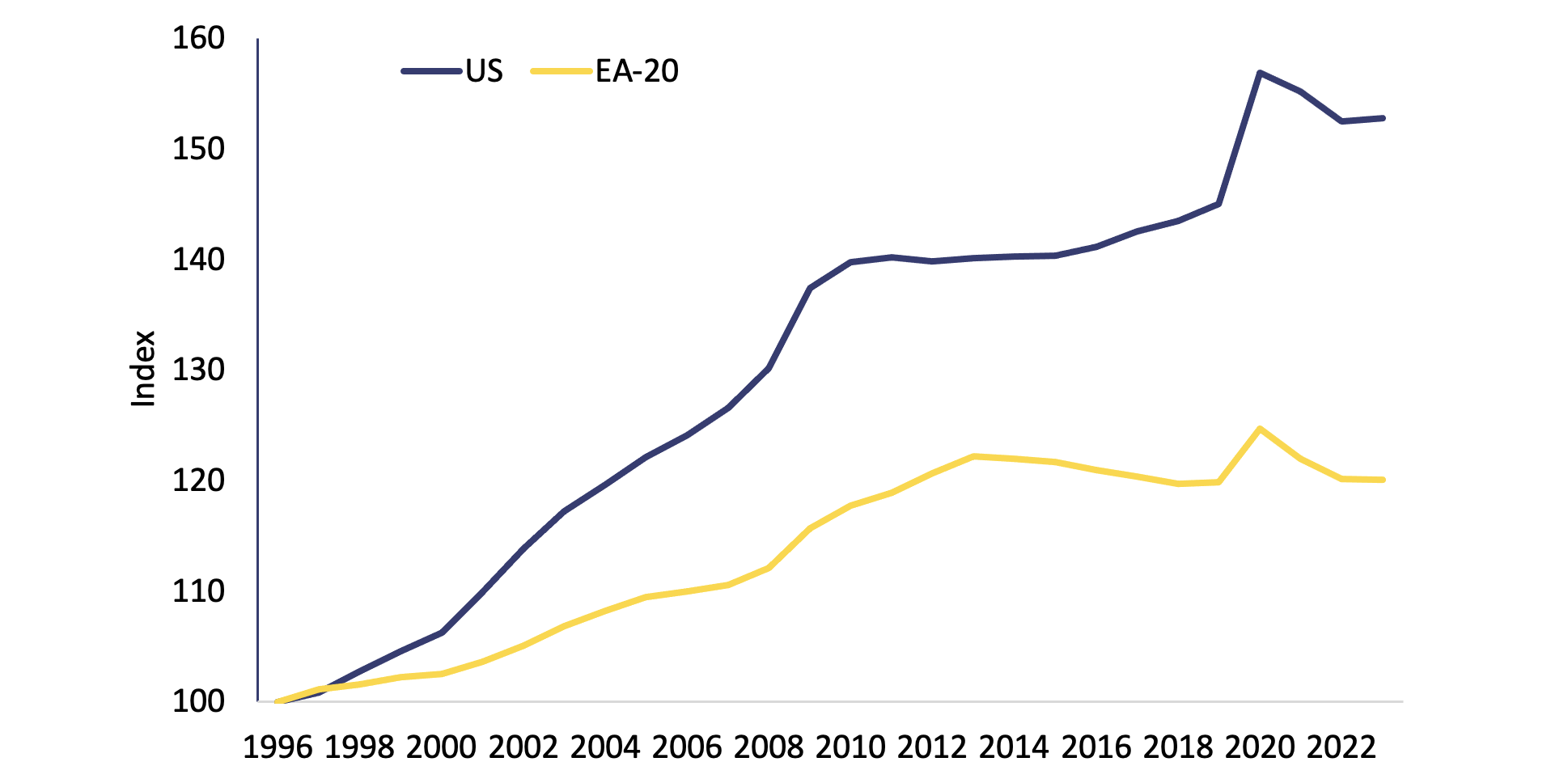

Amid deep economic transformation due to the green and digital transition, the euro area needs substantially more investment. Greater investment boosts labour productivity and drives innovation, enhancing overall productivity (McMorrow et al. 2010). Compared to the euro area, the US has seen a much faster increase in capital intensity per worker over the past 25 years (Figure 3) and contributed to strong potential growth in the US.

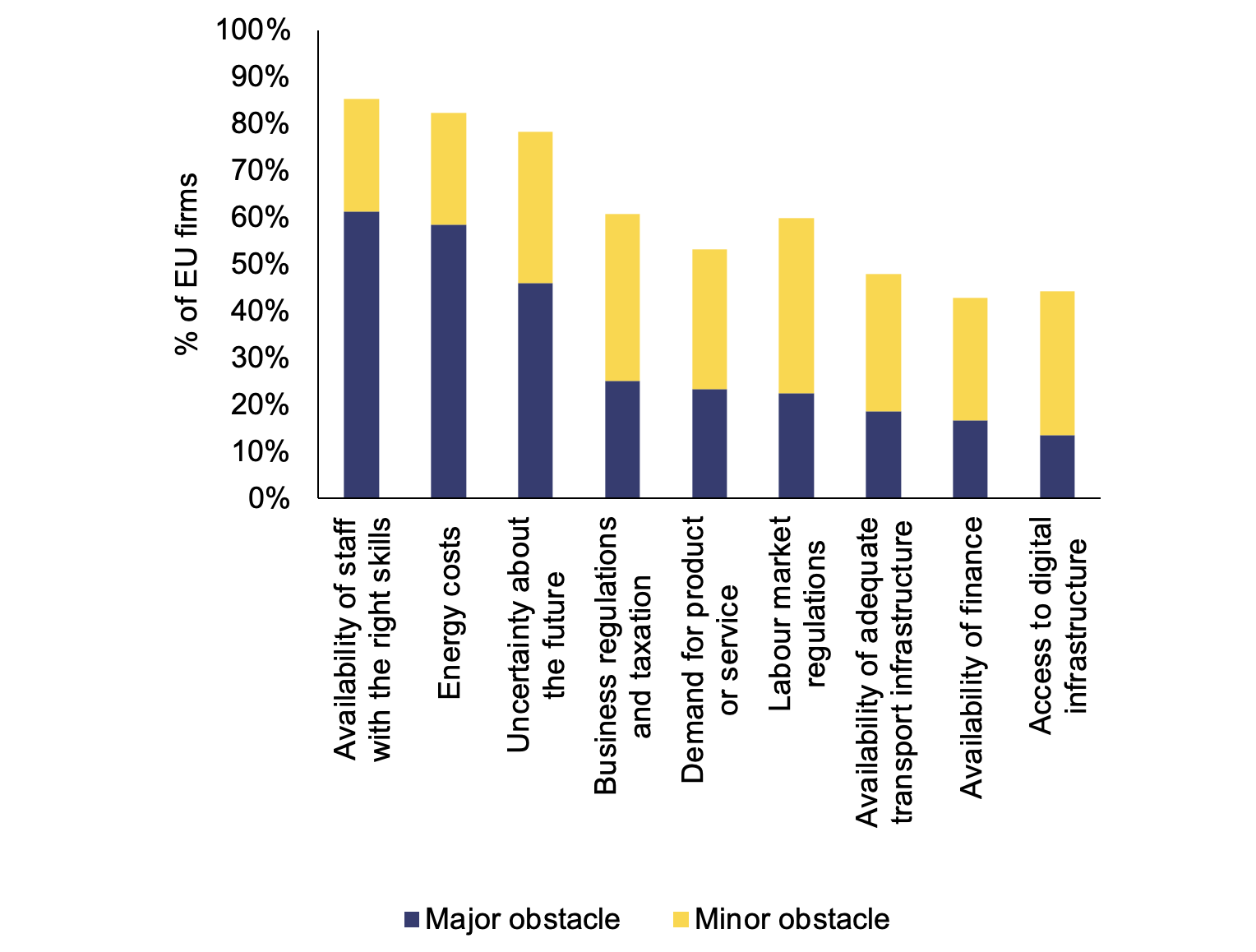

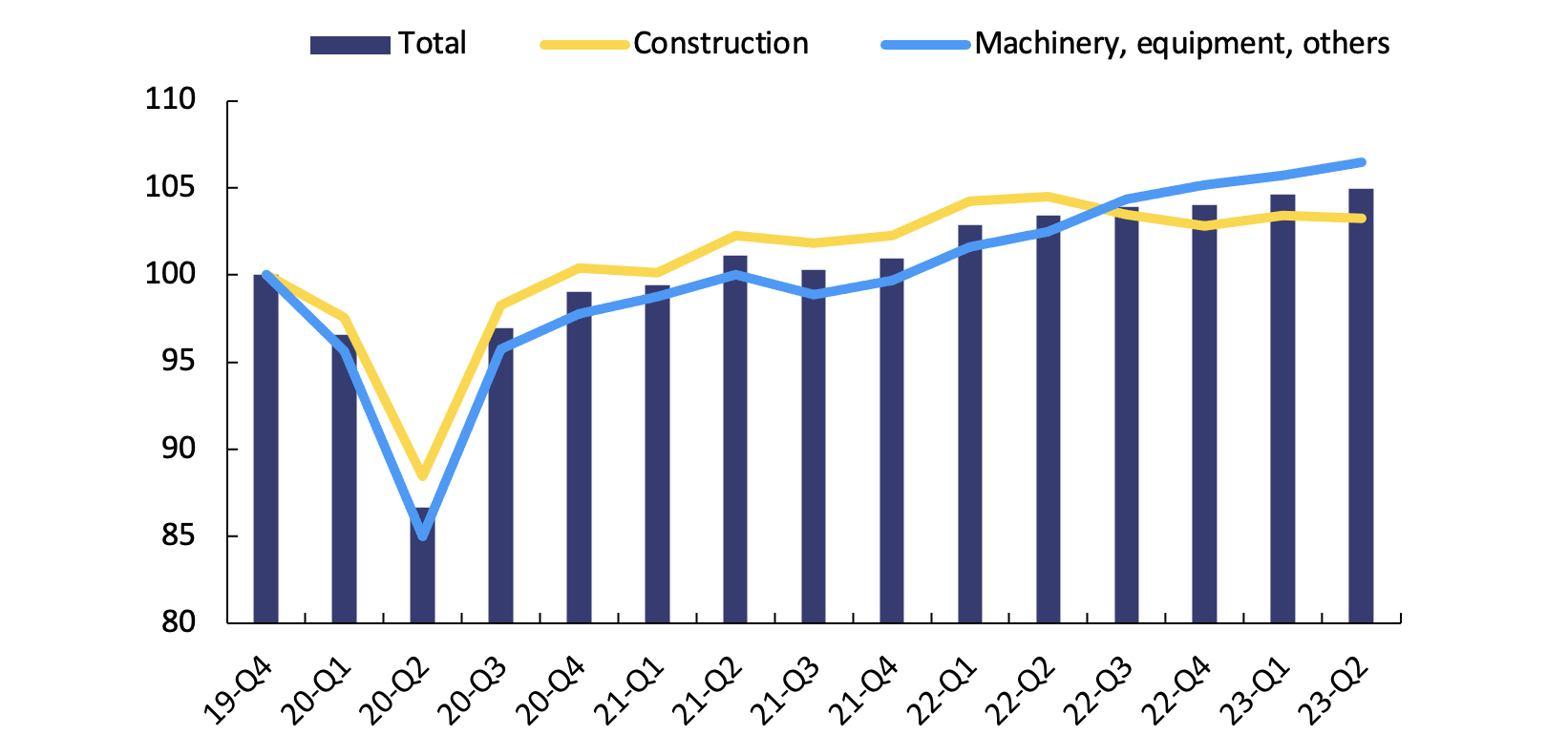

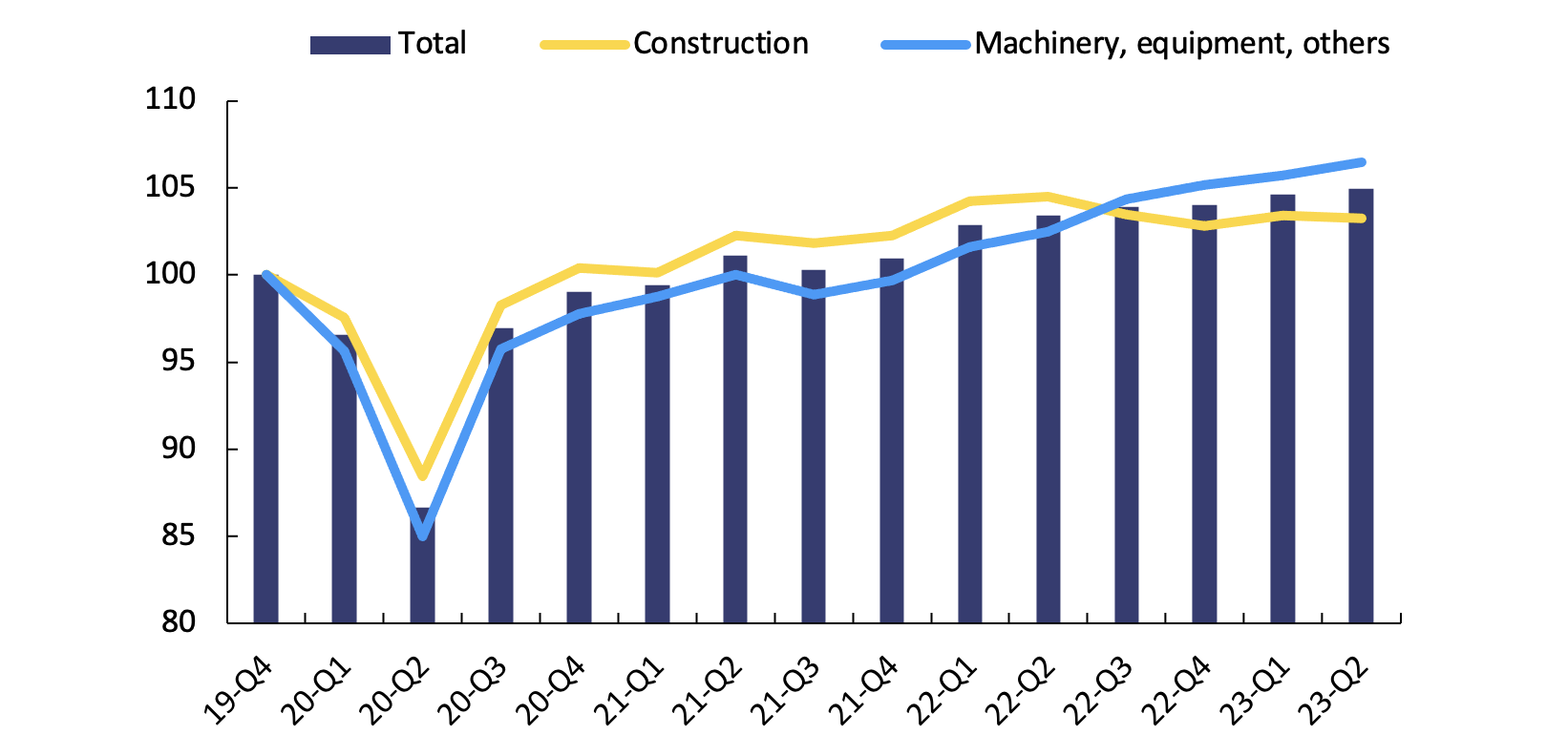

Since 2019, investment spending on equipment and infrastructure in the euro area has held up, supported by solid corporate balance sheets. Still, major challenges to investment persist, including a shortage of skilled labour and increasing energy costs (Figure 4). Administrative hurdles, linked in particular to permitting, also undermine investment in the green transition. Going forward, the higher interest rates are set to weigh on investment, particularly on projects with a long time horizon such as research and development. This calls for proactive policies to further support investment, both public and private, in the euro area.

Public investment received a significant boost from the EU through the Recovery and Resilience Facility (RRF), REPowerEU, and cohesion policy funds. The RRF, which is at the heart of the Next Generation EU recovery instrument, makes available €723 billion in grants and loans to Member States until 2026 to support investment and reforms. It helps reconcile fiscal consolidation and public investment needs across the euro area. Two years into implementation, the RRF has contributed to the recovery in public investment (Figure 5), including deployment of green technologies, modern digital infrastructures, and green and digital skills development. About €220 billion have been disbursed under the RRF to euro area Member States until now. The RRF is also expected to crowd in more private investment (Pfeiffer et al. 2023).

Cohesion policy funds are a more lasting form of EU support that provides Member States with an additional €392 billion to invest in the green and digital transitions over 2021–2027. Along with investment in physical capital, national recovery and resilience plans also support human capital accumulation. Some plans support up- and re-skilling workers that can boost productivity and support the green and digital transition while reducing skills shortages and mismatches.

Figure 3 Capital intensity in the euro area and the US

Note: Net capital stock at 2015 prices per person employed; total economy. Source: AMECO.

Figure 4 Perception of long-term barriers to investment (% of EU firms)

Notes: (1) Survey answers for question: ‘Thinking about your investment activities, to what extent is each of the following an obstacle? Is a major obstacle, a minor obstacle, or not an obstacle at all?’ (2) Data for all surveyed firms from all sectors; data for answers for ‘no obstacle’ and ‘don’t know/refused’ are not shown.

Source: European Investment Bank Investment Survey (2022).

Concrete progress towards a true Capital Markets Union would help boost private investment and finance innovation. The lingering fragmentation of European capital markets along national lines hinders access to finance and, in turn, innovation and competitiveness (European Commission 2023d). Fragmented capital markets imply lower competition among financial institutions, high liquidity premia, and eventually a higher cost of funding. There is a strong correlation between greater access to capital markets and lower cost of funding (Figure 6). Robust and liquid capital markets can provide alternatives to bank financing, in particular for innovative companies and start-ups. A deeper Capital Markets Union would thus support private investment while minimising the need for government support.

Figure 5 Investment sectoral breakdown, euro area (volumes, 2019 = 100)

Notes: (1) Public and private investment volumes are calculated based on total investment deflator. (2) Public investment includes aggregates of general government gross fixed capital formation (GFCF) and GFCF financed with RRF grants.

Source: European Commission.

Figure 6 Cost of borrowing for firms and the share of non-financial corporation (NFC) listed equities and debt security over total NFC liabilities

Source: European Central Bank and OECD.

More generally, deepening the Single Market would provide opportunities to unlock growth and strengthen competitiveness. More than 30 years after the creation of the Single Market, the EU still needs to take full advantage of its sheer size – 450 million citizens, larger than the US population of 330 million – and its potential to increase private investment and innovation (European Commission, 2023e). Intensifying EU integration and reducing remaining barriers within the internal market would lead to substantial welfare gains for the euro area and the EU (Baba et al. 2023). As risks of geopolitical fragmentation increase (Gaal et al. 2023), deepening the Single Market would also increase the euro area’s resilience. Given its greater trade openness, the euro area has much to lose from a reversal of the global integration of the past decades. In that context, the EU’s large and diverse membership, including advanced and emerging market economies, provides the scope and scale to build European-based supply chains.

Greater coordination of Member States’ industrial policies, building on EU instruments, would help companies reap the benefit of the Single Market. In response to the COVID-19 and energy crises, Member States have stepped up support to companies, including in the form of state aid. However, the proliferation of national schemes runs the risk of destabilising the level playing field within the Single Market. Absent some coordination in industrial strategy, larger Member States or those with greater fiscal space may have greater scope to support companies, to the partial detriment of other euro area countries and the integrity of the Single Market (Gopinath 2023). Not fully exploiting the economies of scale at the EU level is also a missed opportunity. Coordinating EU-wide financial support for business investment, as through the Commission’s proposed Strategic Technologies for Europe Platform (STEP), would allow a more consistent industrial policy across the euro area.

Conclusion

In the short term, careful policy coordination is crucial to continue supporting the smooth disinflation process and to keep in place the conditions for a gradual recovery of the euro area economy. At the same time, in a year of elections for the EU and as the euro celebrates its 25th anniversary, an ambitious economic agenda is called for to restore the euro area’s competitiveness and spur long-term growth. Boosting investment and fostering innovation are essential to support productivity and achieve the ongoing green transition. Greater use of the Single Market’s potential and more coordinated industrial strategies offer possibilities to accelerate economic growth and bolster competitiveness in the euro area.

References

Baba, C, T Lan, A Mineshima, F Misch, M Pinat, A Shahmoradi, J Yao, and R van Elkan (2023), “Geoeconomic fragmentation: What’s at stake for the EU”, IMF Working Paper 23/245.

Coutinho, L, and M Licchetta (2023), “Inflation differentials in the euro area at the time of high energy prices”, Economy Discussion Paper 197.

European Central Bank (2023), Macroeconomic projection (December 2023).

European Commission (2023a), European economic autumn 2023 forecast, European Economy Institutional Paper 258, DG ECFIN, November.

European Commission (2023b), Recommendation for a Council Recommendation on the economic policy of the euro area, COM(2023) 903 final.

European Commission (2023c), Business and consumer survey, October.

European Commission (2023d), Euro area report, European Economy Institutional Paper 259, DG ECFIN, December.

European Commission (2023e), Communication on the Single Market at 30, COM (2023) 162 final.

European Investment Bank (2022), EIB investment survey 2022: European Union overview.

Gaal, N, L Nilsson, J R Perea, A Tucci, and B Velazquez (2023), “Global trade fragmentation. An EU perspective”, Economic Brief 075, September 2023.

Gopinath, G (2023), “Europe in a fragmented world”, IMF First Deputy Managing Director Remarks for the Bernhard Harms Prize.

IMF (2023), Regional economic outlook Europe, November.

McMorrow, K, W Roeger, and A Turrini (2010), “Determinants of TFP growth: A close look at industries driving the EU-US TFP gap”, Structural Change and Economic Dynamics 21: 165–80.

Pfeiffer, P, J Varga and J in ‘t Veld (2023), “Quantifying spillovers of coordinated investment stimulus in the EU”, Macroeconomic Dynamics 27.