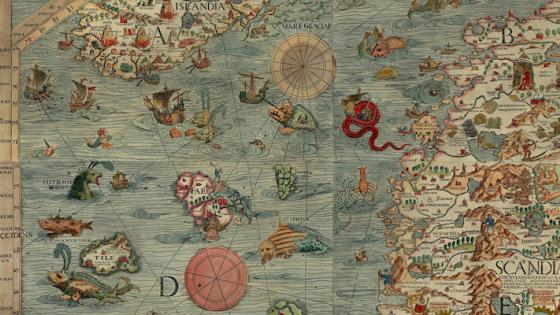

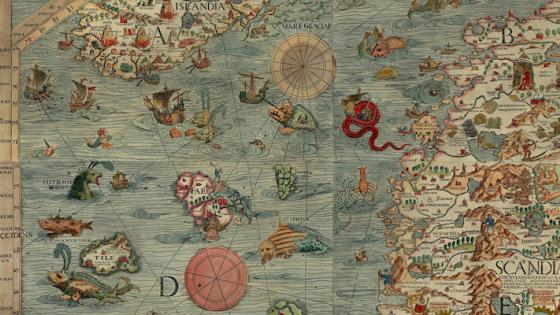

Here be dragons

Volatility is only a good measure of risk when shocks are distributed normally. This post argues that extreme value theory offers a better, if imperfect alternative. Even better would be to use more fundamental analysis.

Search the site

Volatility is only a good measure of risk when shocks are distributed normally. This post argues that extreme value theory offers a better, if imperfect alternative. Even better would be to use more fundamental analysis.

First posted on:

modelsandrisk.org, 7 October 2017.

Medieval mapmakers noted the risk of an unknown kind with ‘here be dragons’. Attempts at measuring extreme risk should come with a similar warning. Just like the sailors of yesteryear, financial institutions will go into unknown territories and, just like the mapmakers of the earlier era, modern risk modellers have little to say.

The most difficult problem in measuring the risk is how to deal with very large and infrequent negative outcomes. Because these big losses don’t happen very often, it is quite difficult to exploit historical observations to predict what sort of losses we might expect in the future. This is known as the fat-tail problem.

Take the Standard & Poor’s 500 index. I have daily observations on the S&P 500 dating back to 1928, finding its daily realised volatility to be 1.1%. Volatility only has a meaning under the normal distribution and it is straightforward to use a combination of the two to project any type of losses I want. If my portfolio is $1,000, the once-in-the-millennium loss is $45. Not so shabby.

Except, of course, it isn’t like that. If I take my 88-year history of daily returns on the S&P 500, I find that the worst average annual loss is $47, not $26 as predicted by the normal. Over time these differences become bigger. The worst day over the past 88 years would give me losses of $229 on 19 October 1987. Using volatility to measure risk would have lulled me into complacency.

I would have been eaten by a dragon.

This is summarised in the following figure which shows both the type of losses I would expect if using the normal distribution and what actually happened.

Volatility can only be an accurate measure of risk if and only if returns are normally distributed. And since they are not, volatility is an insufficient, and possibly a very misleading, measure of risk.

Oftentimes it doesn’t really matter all that much; the simplicity of volatility is all that we need in most cases. If, however, we do care about the dragons, then beware: they only bite us in times of stress. Volatility cannot tell us anything about when that will happen.

Next time you hear someone use volatilities or standard deviations as measures of risk, especially extreme risk, remember that it is not so.

There is nothing new about this analysis: researchers have known about the fat tail problems for over 50 years, ever since the 1963 work of future Nobel Prize winner Eugene Fama and his PhD advisor, Benoit B. Mandelbrot.

Still, even people and institutions that we would expect to know better can express surprising views on tail risk.

So if volatility and the normal distribution are not sufficient, what can we do? There are strategies, but none are easy. It requires better-trained staff, faster computers, more time to create models; it is more expensive to hedge against tail risk and is harder to explain. So, it is about resources and communication and expectations. It is hard enough to talk about volatility in an accurate way to non-specialists, and any discussion of fat tails tends to go over the heads of most decision-makers.

There are two different avenues one can take. The first is based on understanding the deep nature of where risk is, how the people who work in the financial system interact, and how they create risk. Use endogenous risk. Perhaps model the political risk.

If that is too complicated, we can just take a purely statistical approach, extreme value theory. EVT is based on using the most extreme outcomes in a sample of observations of some object of interest to project the tail of the distribution of those objectives all the way to infinity.

As the next figure shows, we get much closer to what has been observed in history and the once-in-a-millennium prediction is certainly much more realistic than the normal distribution predicts.

It isn’t perfect: EVT depends on strong distributional assumptions likely to be violated in practice and it is difficult to find the right tuning parameters for the procedure. Still, it is the only game in town when it comes to using a purely statistical procedure to forecast extreme losses.

Still, instead of just relying on statistics, it is much better to look at the fundamentals.