During the pandemic, around 26 million young adults in the US returned to live with their parents (Fry et al. 2020). A recent survey suggests that two-thirds of ‘Millennials’ and ‘Generation Z’ who moved back with their parents at the peak of the pandemic still live there, more than two years later (Ceizyk 2022). However, this is a trend that started well before COVID-19.

A 2012 survey found that 39% of 18–34 years olds were living with their parents or had moved back for some time, with young adults outpacing other groups in multigenerational living (Pew Research Center 2012). This trend is dominated by college graduates. Figure 1 shows that, on average, 31% of the 2013 college graduation cohort resided with their parents at age 23 to 27 years old, compared to only 25% for the 1996 graduation cohort.

Figure 1 The rise in co-residence for college graduates

Notes: Co-residence rate for college graduates aged 23–27 not enrolled in school. College graduates hold bachelor’s degrees. Co-residence rate is defined as the average share of college graduates that live with either of their parents in the survey month.

Source: Albanesi et al. (2022).

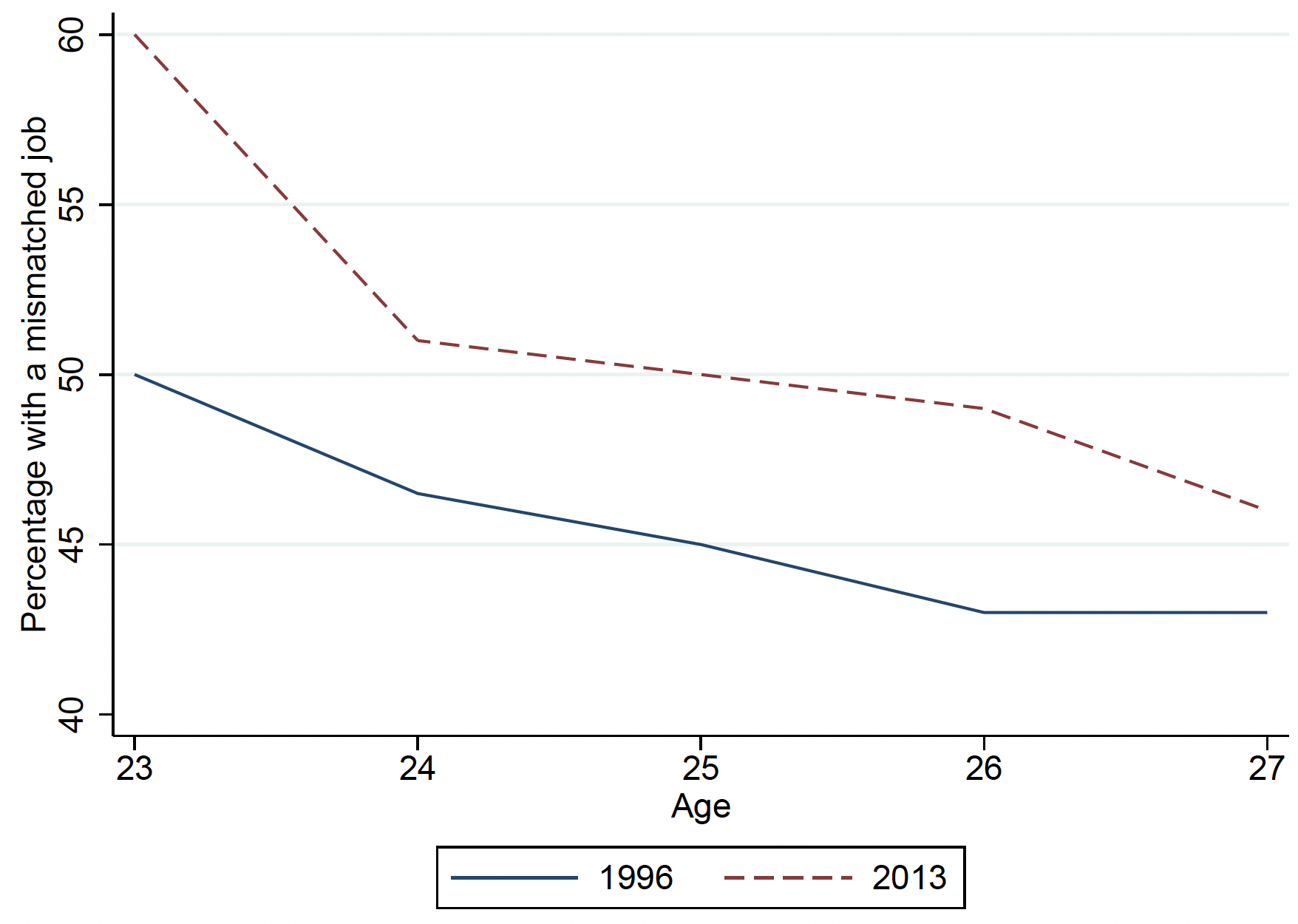

What is driving the rise in co-residence for young college graduates? The worsening of labour market conditions for college graduates in the last two decades likely contributed. In our recent study (Albanesi et al. 2022), we focus specifically on the rise in ‘job mismatch’, that is, the incidence of college graduates employed in jobs that do not require a college degree. Figure 2 shows that the job mismatch rate for the 2013 graduation cohort at age 23 to 27 years is around 52% on average, which is 7% higher than for the 1996 graduation cohort at the same age.

Figure 2 The rise in the job mismatch rate

Notes: Job mismatch rate for college graduates aged 23–27 not enrolled in school. College graduates hold bachelor’s degrees. Data from Survey of Income and Program Participation (1996 and 2014) and Department of Labor, O*NET Education, Experience, Training.

Source: Albanesi et al. (2022).

In addition to the lower availability of suitable jobs, young college graduates also experience a rise in unemployment, as shown in Figure 3. The unemployment rate at ages 23 to 27 years old is 30% higher for the 2013 college graduation cohort compared to the 1996 cohort, increasing from an average of 9% to 12%.

Figure 3 The rise in unemployment for college graduates

Notes: Unemployment rate for college graduates aged 23–27 not enrolled in school. College graduates hold bachelor’s degrees. Data from Survey of Income and Programme Participation (1996 and 2014) and Department of Labor, O*NET Education, Experience, Training.

Source: Albanesi et al. (2022).

We argue that, faced with an increase in job mismatch and unemployment, young college graduates choose co-residence. This enables them to weather spells of unemployment and low wages in mismatched jobs in the short run and to wait for a ‘matched’ job, eventually leading to higher future earnings. This notion is supported by empirical evidence.

We show that young college graduates who are employed are less likely to co-reside with their parents than those who are unemployed and that those who work at a matched job are less likely to co-reside than those working at a mismatched job. These findings suggest that labour market performance is inversely related to co-residence in the short run.

Additionally, college graduates who at age 23 are either unemployed or working at a mismatched job have monthly earnings that are 17% lower than those working at a matched job by age 27. For those who do not co-reside or move back with their parents at the time of unemployment or mismatched-job spell, earnings at age 27 are 26% lower; in contrast, there is no earning impact on those who co-reside or move back with their parents. Hence, co-residence is estimated to have a strong positive effect on future earnings for young college graduates experiencing adverse labour market conditions.

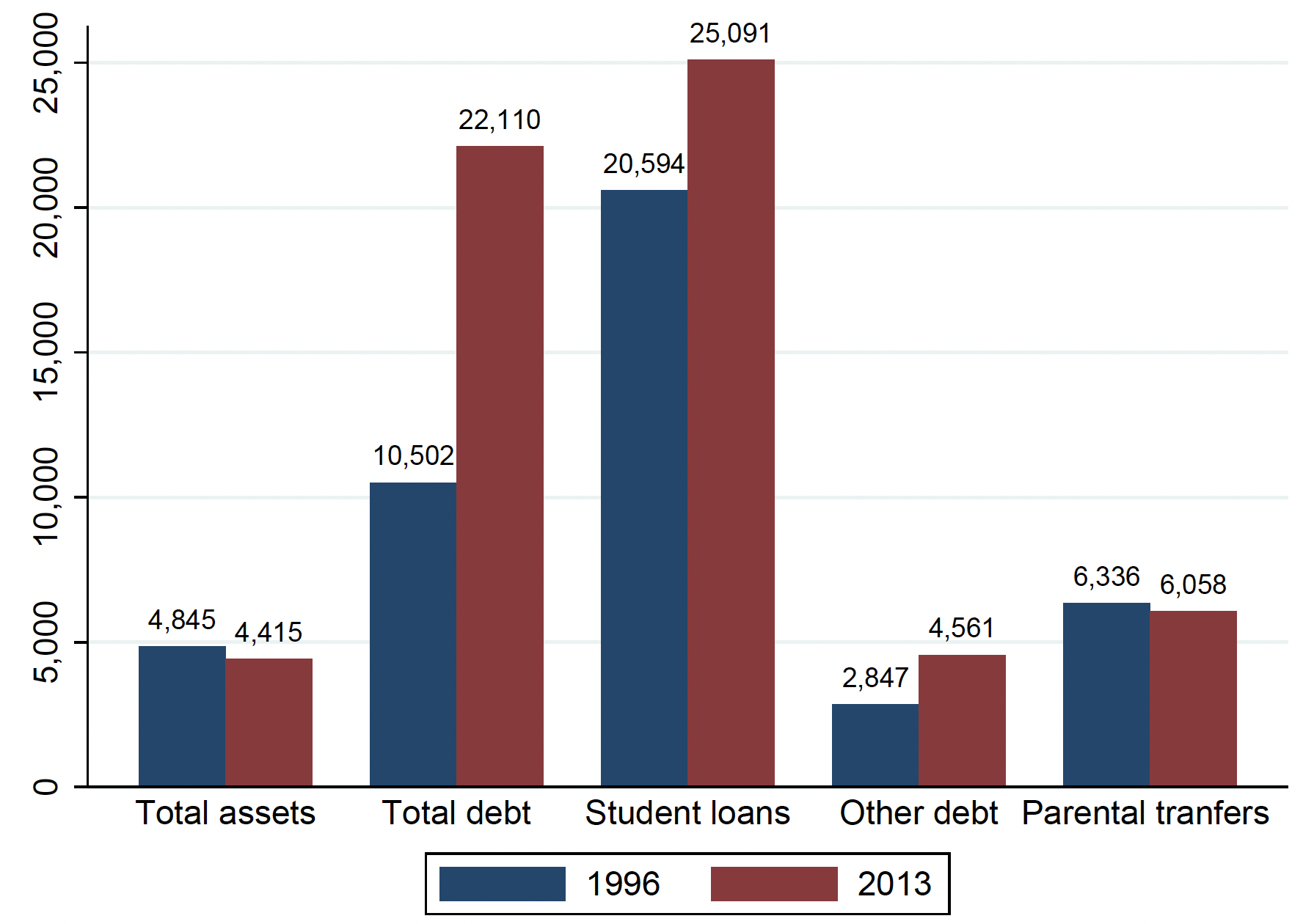

While this evidence suggests a link between worsening labour market conditions for young college graduates and co-residence, other factors may also have played a role. The fraction of college graduates with education loans increased from 18% for the 1996 graduation cohort to 41% for the 2013 cohort. Average balances among those with student debt went up by $5,000 to more than $25,000 because of increasing college tuition and fees (Narayan et al. 2016). Meanwhile, transfers from parents decreased because of the adverse impact of the 2007–2009 housing crisis and recession on net worth, as can be seen in Figure 4. Rental costs also rose, and wage dispersion increased throughout the labour market, raising the option value of unemployment.

Figure 4 Assets of college graduate cohorts, 1996 vs 2013

Notes: Values are for 23- to 27-year-old college graduates in the 1996 and 2013 graduation cohorts. Total assets include savings accounts, checking accounts, stocks, mutual funds, and bonds. Total debts include student loans and other debts, where other debts include credit card loans and debt on stocks or bonds. Net assets are defined as total assets minus total debts. Parental transfers are the amount of dollars transferred from parents during the survey year. All values reported are in real terms, CPI adjusted to 2014 dollars.

Source: Albanesi et al. (2022).

To jointly determine the quantitative impact of all these factors on co-residence, we develop a structural model of child-parent decisions, where co-residence status and labour market outcomes for the children are jointly determined as a function of earnings, assets, family characteristics, and preferences. In the model, by deciding to reside with their parents, college graduates can remain unemployed and wait for a matched job rather than accept a mismatched job. If the rate of arrival of matched jobs declines, more college graduates will choose to reside with their parents. We estimate the model using the 2014 Survey of Income and Programme Participation to account for the differences in living arrangements, unemployment, and earnings between the 1996 and 2013 college graduation cohorts.

The model allows us to break down the impact of changes in the matched-job arrival rate, earnings dispersion, student-debt burden, parental income, and rental costs. These factors can jointly explain all the difference in unemployment rates, 54% of the difference in matched job rates, and 68% of the difference in co-residence rates between the 1996 and 2013 college graduation cohorts.

We use the model to assess the relative strength of each of the channels. We find that the decline in the matched-job arrival rate and rise in earnings dispersion have the largest effect on changes in unemployment. The rise in earnings dispersion has a large impact on co-residence, jointly with the rise in student-debt burdens and rising rental costs. We also find that changes in preferences over marriage and household formation are important in shaping the evolution of co-residence behaviour between the two graduation cohorts.

Even with the rise in job mismatch and unemployment for college graduates, college graduates face higher employment rates and lifetime earnings and lower unemployment rates than individuals without a college degree (see, among many others, Card 1999, Mortenson 2001, Harmon et al. 2003). However, not all college graduates are able to reap the benefits of a college education. Given the changes in the landscape, high schools and universities should be more active in helping and preparing students to navigate the increasingly challenging labour market as young college graduates, especially given how knowledge of labour market opportunities can influence students’ choice of major (Marinescu et al. 2017).

References

Albanesi, S, R Gihleb, and N Zhang (2022), “Boomerang college kids: Unemployment, job mismatch and coresidence”, CEPR Discussion Paper No. 17627.

Card, D (1999), “The causal effect of education on earnings”, in O Ashenfelter and D Card (eds), Handbook of Labor Economics (Vol. 3A), Amsterdam: Elsevier.

Ceizyk, D (2022), “Two-thirds of Millennials and Gen Zers who moved back home during the pandemic still live there”, LendingTree, 30 August.

Fry, R, J S Passel, and D Cohn (2020), “A majority of young adults in the US live with their parents for the first time since the Great Depression”, Pew Research Center, 4 September.

Harmon, C, H Oosterbeek, and I Walker (2003), “The returns to education: Microeconomics”, Journal of Economic Surveys 17(2): 115–56.

Marinescu, I, E Bettinger, B Jacob, and R Baker (2017), “Major decisions: How labour market opportunities affect students’ choice of subjects”, VoxEU.org, 11 May.

Mortenson, T (2001), “Individual economic welfare in the human capital economy 1973 to 2000”, Postsecondary Education Opportunity 114: 1–16.

Narayan, A, L Giuliano, A Filipek, J Furman, and S Black (2016), “Student loans and college quality: Effects on borrowers and the economy”, VoxEU.org, 4 August.

Pew Research Center (2012), “The boomerang generation”, 15 March.