Central bank independence is understood to be a pillar of sound macroeconomic policy. However, it frequently comes under threat from politicians. Also in the United States, the political dimension of monetary policy has attracted renewed attention. President Donald Trump openly criticised the Federal Reserve, with recent research finding that his pressure impacted market expectations of monetary policy (Kind et al. 2020).

A large literature in economics has studied the benefits of politically independent central banks across countries (e.g. Alesina and Summers 1993). Other studies have focused on the interaction between fiscal and monetary policy within an economy through time (e.g. Bianchi and Ilut 2017). While the first literature relies on cross-country comparisons and the second one on fully specified structural models, there is little well-identified empirical evidence on how political pressure on the Fed affects the US economy quantitatively through time.

In a recent paper (Drechsel 2023), I construct new data and develop a narrative identification strategy to isolate exogenous ‘political pressure shocks’ on the Fed and quantify their effects on the US economy.

New data on interactions between the president and the Fed

I hand-collected new data on personal interactions between US presidents and Fed officials. The source of the data are the historical daily schedules of US presidents, made available by the Presidential Libraries from Franklin D. Roosevelt in 1933 until Barack Obama in 2016. The daily schedule of the US president is constructed as a detailed minute-by-minute log of meetings and events with time, place, duration, type, and who the president interacted with. The document quality ranges from searchable digital form to poor typewriter quality that requires manual reading on site.

I find over 800 personal interactions with Fed officials in these archival records. The average duration of an interaction is 53 minutes; 36% of the interactions are one-on-one; 11% are on weekends; 16% in social settings (e.g. over dinner); 92% of the interactions are with the Fed Chair, 8% with other Fed officials.

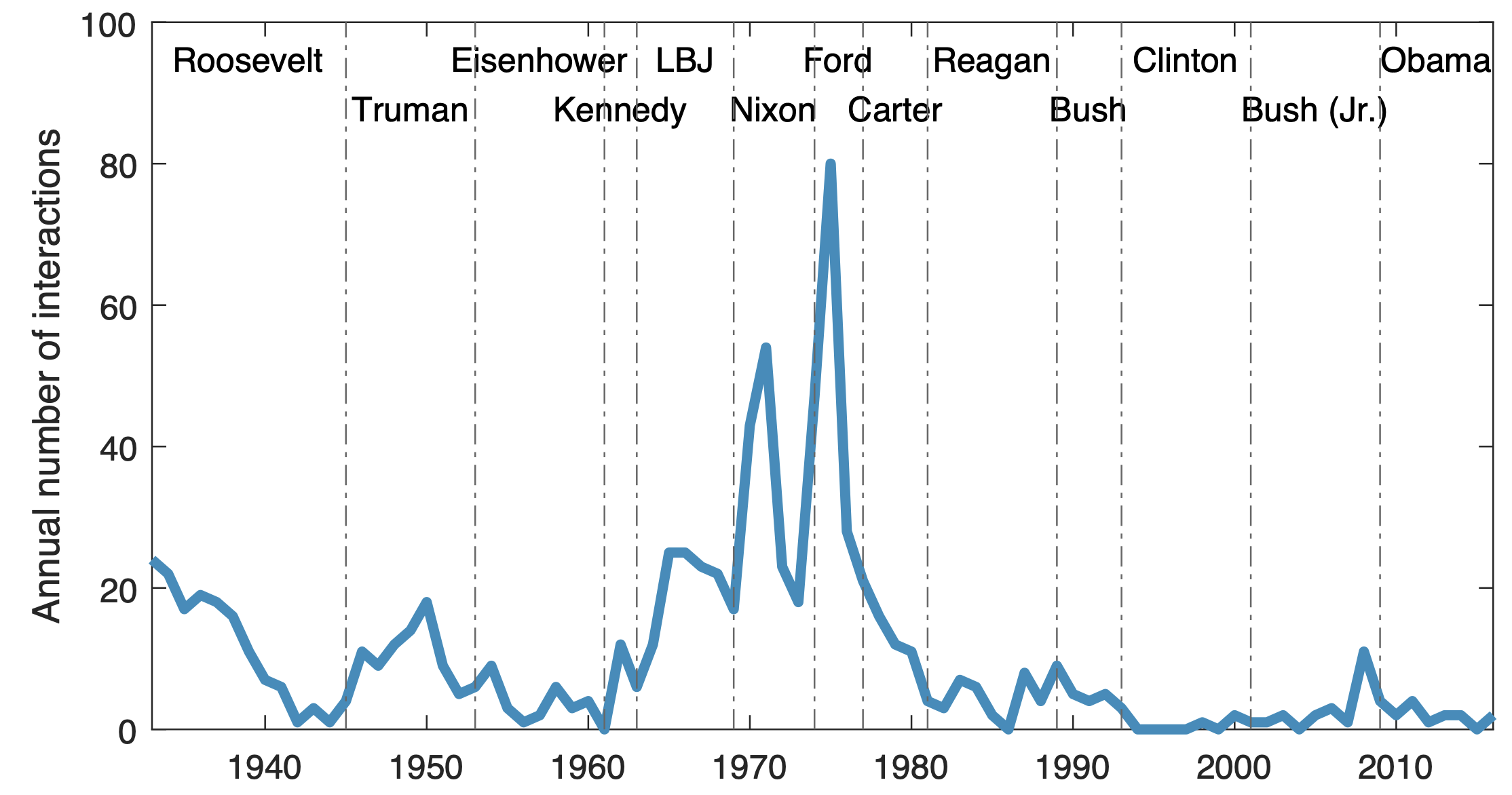

Using this data set, I construct new time series of ‘president–Fed interactions’. As shown by Figure 1, there is a large variation in these personal interactions over time. For example, President Nixon interacted with Fed officials 160 times, while only six interactions took place during the Clinton administration.

Figure 1 Annual number of president-fed interactions through time

Narrative approach exploiting Nixon’s pressure on the Fed

The data on personal interactions by themselves are at best a noisy measure of political interference with the Fed. For example, in a recession the president might be more likely to contact the Fed chair and ask them about their view on the economy. In this instance, personal interactions would increase, but not because they reflect political pressure.

To overcome this identification challenge, I exploit an increase in president–Fed interactions that plausibly took place purely for the purpose of influencing Fed policy and arguably had an impact on the stance of monetary policy. In his desire to be re-elected in 1972, Richard Nixon pressured Arthur Burns to ease monetary policy in 1971. Burns, a Republican and friend to Nixon, reportedly gave in to Nixon's pressure.

A variety of external evidence corroborates this interpretation of the Nixon–Burns clash, including recordings from the ‘Nixon tapes’ and entries in Arthur Burns’ personal diary. For example, Burns writes in his diary that Nixon urged him “start expanding the money supply and predicting disaster if this didn’t happen”. To support the interpretation that Burns eased policy in response to Nixon’s pressure, I show that Romer and Romer (2004) uncover easing shocks to monetary policy prior to Nixon's re-election. I also present supporting evidence from the voting behavior of the FOMC.

I exploit the narrative around Nixon's pressure in a structural vector autoregression (SVAR) that contains the president–Fed interactions as well as standard macro data. I identify a shock to political pressure on the Fed based on narrative sign restrictions (Antolin-Diaz and Rubio-Ramirez 2018). Specifically, I define a political pressure shock as an increase in president-Fed interactions that eases policy in an inflationary way and constitutes the main contributor to the spike in president–Fed interactions in late 1971.

The macroeconomic effects of political pressure shocks

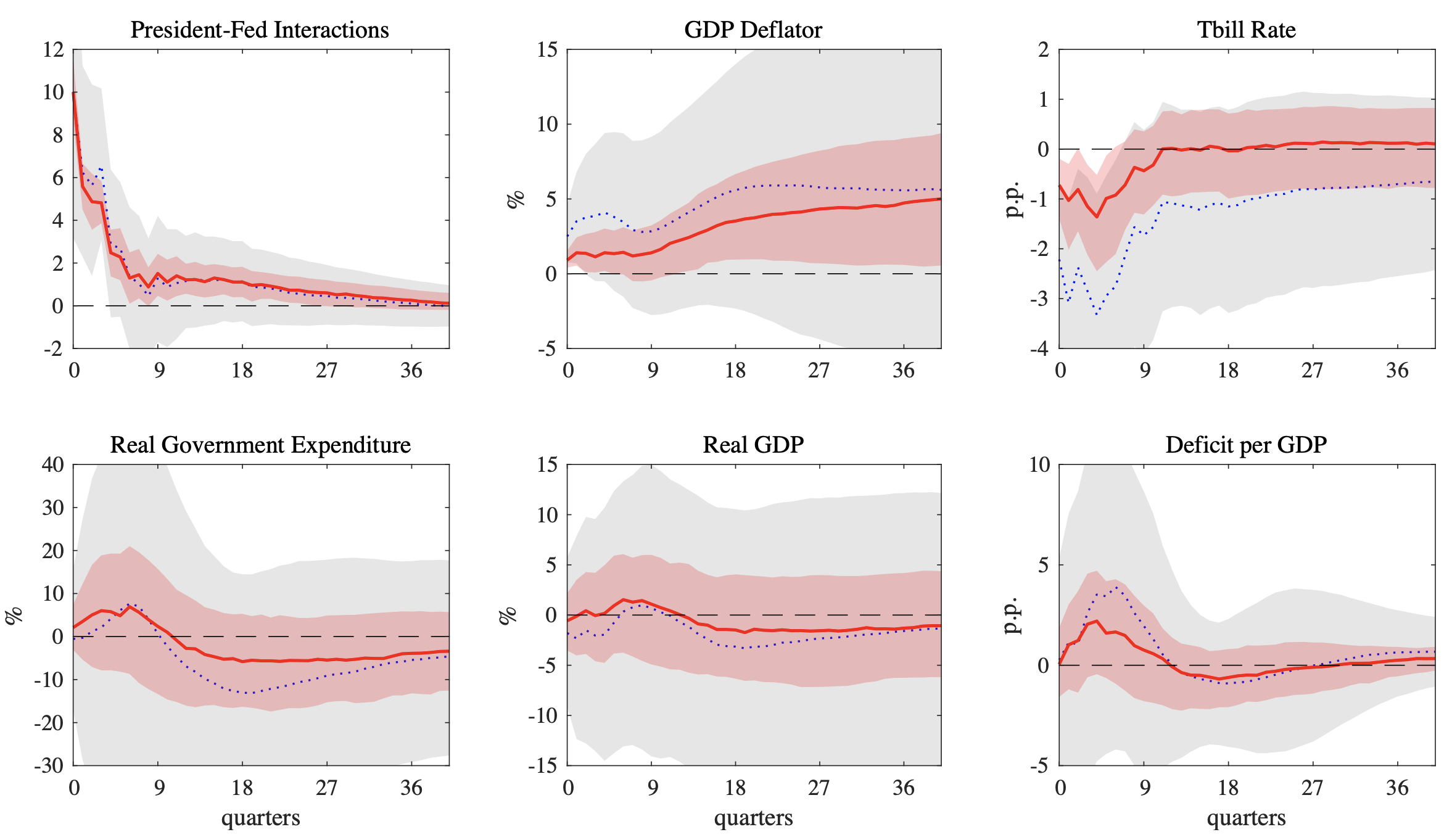

Figure 2 presents the impulse response function (IRFs) to a political pressure shock. The red shaded areas represent 68% posterior credible intervals. For comparison, I also show as dotted blue lines with grey shaded areas the IRFs to a shock identified from only imposing the standard sign restrictions that define the shock, but without imposing the narrative restriction that draws on Richard Nixon's behaviour. I normalise the shock to raise the number of personal president–Fed interactions by ten in one quarter. This is a large shock relative to what happens during a typical Presidency, but not compared to Nixon’s 17 meetings per quarter in late 1971.

Figure 2 IRFS to a political pressure shock over the full sample

The number of president–Fed interactions displays persistence after the political pressure shock hits, with the IRF reversing to closes 0 after around two years. The shock induces a monetary easing, with a roughly 100 basis points lower interest rate after a few quarters. The price level response to the shock builds up gradually and persistently and reaches a 5% higher price level after four years. These estimates imply that exerting political pressure 50% as much as Nixon did, over a period of six months, permanently increases the US price level by more than 8%.

The responses of real GDP and fiscal variables are not distinguishable from zero. This finding indicates that political pressure primarily induces a price level effect. It turns out that in some subsamples (not shown here), it is possible to detect a significant response of real GDP, but this response is actually negative.

Considering the superimposed IRFs that do not use the narrative (in grey), it is visible that these are much less precisely estimated. This underscores that my narrative identification approach is critical to uncover the economic consequences of political pressure on the economy.

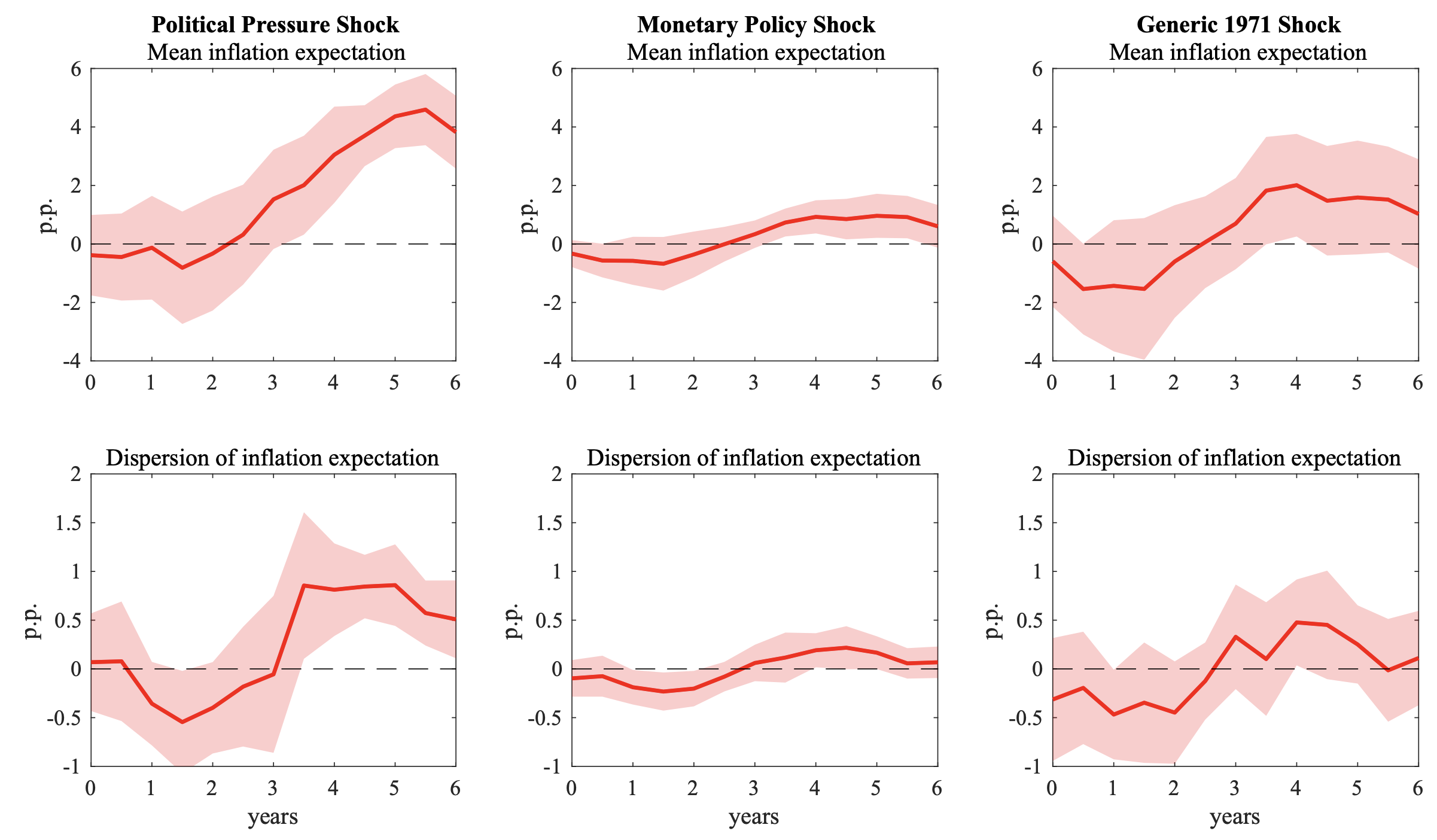

Figure 3 shows IRFs of the mean and dispersion of inflation expectations from the Livingston Survey to a political pressure shock. The figure compares these to the IRFs following a standard monetary policy easing shock and a generic ‘1971 inflationary shock’ (defined based on being important during the Nixon re-election campaign but not informed by the president–Fed interaction data). It is visible that political pressure shocks have a strong impact on inflation expectations and their dispersion.

Figure 3 The response of inflation expectations to different shocks

In my paper, I drill down on these results from numerous additional angles and provide several robustness checks. For example, I add a second narrative episode based on President Lyndon B. Johnson’s pressure on Fed Chair William McChesney Martin, which strengthens my result.

Taken together, these findings do not only underscore existing insights from cross-country studies on the benefits of central bank independence. They also constitute novel evidence that is quantitative in nature and from within the US economy over a long sample, which to the best of my knowledge has not previously been obtained. My analysis might help gauge the effects of potential future episodes of US presidents pressuring the Federal Reserve.

References

Antolin-Diaz, J and J Rubio-Ramirez (2018), “Narrative Sign Restrictions for SVARs”, American Economic Review 108: 2802–29.

Alesina, A and L Summers (1993), “Central bank independence and macroeconomic performance: some comparative evidence,” Journal of Money, Credit and Banking 25: 151–162.

Bianchi, F and C Ilut (2017), “Monetary/fiscal policy mix and agents’ beliefs”, Review of Economic Dynamics 26: 113–139.

Drechsel, T (2023), “Estimating the Effects of Political Pressure on the Fed: A Narrative Approach with New Data”, CEPR Discussion Paper No. 18612.

Kind, T, H Kung and F Bianchi (2020), “Threatening central bank independence one tweet at a time”, VoxEU.org, 25 January.

Romer, C and D Romer (2004), “A New Measure of Monetary Shocks: Derivation and Implications,” American Economic Review 94: 1055–1084.