The decade of 1985–1995 saw the greatest reduction in global trade barriers in world history. Developing countries from Latin America to South Asia slashed their import restrictions and adopted more market-oriented policies. The fall of the Berlin Wall and the collapse of communism led Eastern European countries to do the same as they rushed to integrate with Western Europe. China and Vietnam remained communist states but opened their economies to the world.

These unilateral actions were reinforced by trade liberalisation at the regional level, such as the expansion and single-market initiative of the European Economic Community in 1986 and the North American Free Trade Agreement in 1994. At the multilateral level, the Uruguay Round of trade negotiations reduced trade barriers, established new trade rules, and created the World Trade Organization (WTO) in 1995.

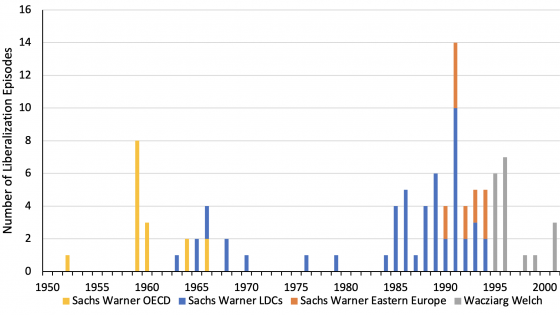

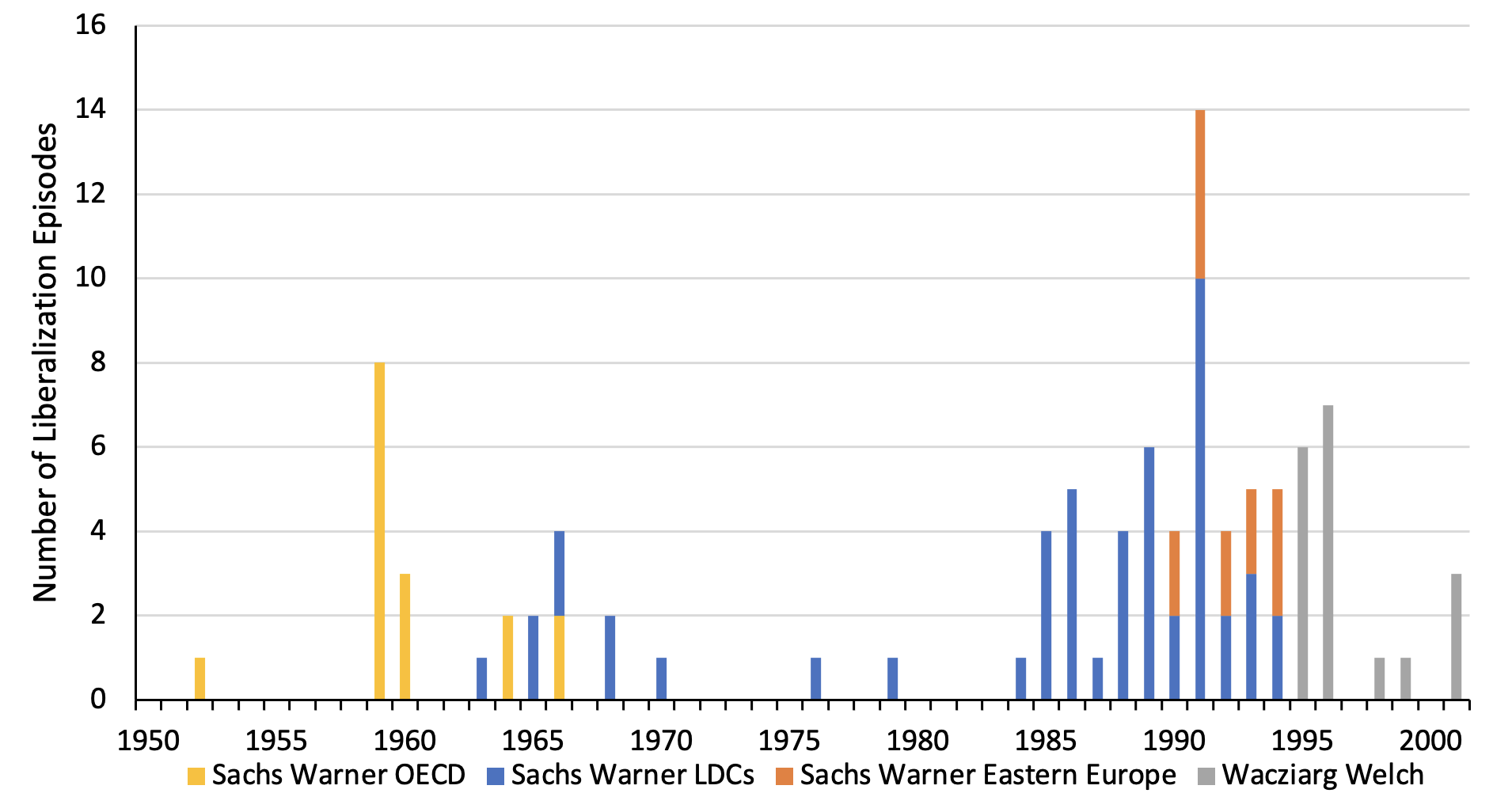

For many OECD countries, this liberalisation was the continuation of a process that began after WWII. For most developing countries, this liberalisation was new and unexpected. Figure 1 shows the number of countries that switched from being ‘closed’ to being ‘open’ after 1950.1 In contrast to the absence of reform in the 1970s, the trade reform wave undertaken by developing countries between 1985 and 1995 stands out.

Figure 1 Number of countries becoming open, 1950–2000

Note: Sachs and Warner (1995). Yellow represents OECD countries, blue represents developing countries, orange represents Eastern European countries, and grey represents other countries later added by Wacziarg and Welch (2008).

This trade reform wave helped create the globalised world of today. What explains the sudden burst of unilateral trade reforms adopted by many developing countries?

Standard explanations come up short. Domestic producer interests usually take centre stage in work on the political economy of trade policy, but changes in the political power of these interests cannot explain this shift.2 The beneficiaries of protection opposed open markets and were just as powerful as they had been in the past, while the beneficiaries of liberalisation, such as exporters, remained politically weak.3 Neither were countries forced to open their economies by the World Bank and IMF. While these institutions supported the policy changes, they were not the driving force behind them. Even the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade was not critical to the reform process.4

My evaluation of the trade reform process (Irwin 2022) focuses on economists’ changing ideas about the use of import restrictions for balance of payments purposes and the increasing number of economists in high-ranking policymaking positions.

In the 1950s and 1960s, most developing countries had fixed but adjustable exchange rates under the Bretton Woods system. They also ran high rates of inflation but resisted devaluation. The failure to adjust nominal exchange rates led them to have overvalued currencies and recurring balance of payments difficulties.5 To restrict spending on imports and avoid a devaluation, countries employed a battery of discretionary controls, including foreign exchange rationing, non-automatic import licensing, and advance import deposit requirements. These controls could be tightened or relaxed depending on the level of a country’s foreign exchange reserves. The rationale for these controls was the balance of payments, not domestic producer interests. Although these policies are sometimes called protectionist, their goal was more the protection of foreign exchange reserves from depletion than the protection of domestic industries from foreign competition.6

In the early postwar period, many economists were sceptical about devaluations and supported import controls and foreign exchange rationing to deal with balance of payments problems. During the 1960s and 1970s, economists accumulated a mounting array of evidence about the costs of these policies and their adverse effect on exports (Little et al. 1970). Discretionary trade intervention and quantitative restrictions were shown to be administratively complex and breeding grounds for special-interest lobbying and corruption. Experience demonstrated that import controls were a bad way of addressing an overvalued exchange rate and a poor substitute for a devaluation (Bhagwati 1978, Krueger 1978). A big shortcoming with trying to conserve foreign exchange reserves through import controls is that they did nothing to increase export earnings.

The changing ideas of economists – recognising the merits of exchange rate adjustment over import controls – helped set the stage for the trade reform wave (Krueger 1997). However, these ideas did not have an immediate influence on policy. They had little impact in the 1970s when developing countries enjoyed an abundance of foreign exchange. In the 1980s, terms-of-trade shocks, the debt crisis, and declining foreign aid forced countries to confront foreign exchange shortages. As a consequence of these difficulties, an increasing number of economists were appointed to senior policymaking positions around the world (Markoff and Montecinos 1993).

These high-ranking economists sought to shift policy from conserving foreign exchange to earning more foreign exchange. They helped tip decisions in favour of devaluation and the liberalisation of import controls when foreign exchange reserves were low and policy adjustments were required. In country after country, high-ranking economists in government – sometimes with past World Bank experience – have been tied to the spread of trade liberalisation (Weymouth and McPherson 2012). Reform teams with advanced degrees from Western universities, such as policy reformers in India who had degrees from Oxford, in Chile who had degrees from Chicago, and in Mexico with degrees from Yale and Harvard, helped bring about policy change.

The first step in the reform process was a devaluation to eliminate any exchange rate overvaluation (evidenced by a black-market premium) and thereby promote exports. This was often followed by the adoption of a more flexible exchange rate regime to prevent the currency from becoming overvalued again. These steps relieved pressure on the balance of payments and allowed import barriers to be relaxed, first by eliminating quantitative restrictions and then by gradually reducing tariffs. The main issue was the exchange rate regime, foreign exchange reserves, and the balance of payments rather than a head-on debate about free trade versus protection. As Collier (1993: 510) put it: “The heart of liberalisation is the conversion from using trade policy for payments balance to using the exchange rate.”

An underrated factor behind the trade reform wave was the ‘third wave’ of democratisation that swept the world in the 1980s and 1990s. To stay in power, autocratic regimes often had to buy the support of elites by granting privileges and sharing rents. Trade controls and the preferential allocation of foreign exchange were among the principal ways of doing this.7 Democracy changed politics in a way that fostered trade reform. As Milner and Kubota (2005) point out, new democracies opened a country’s political system to previously disenfranchised groups and broke up established coalitions of interest groups and political leaders where trade policy (and foreign exchange scarcity) had been used for political purposes.8

Although the open trading system is under pressure today, there is no doubt that the trade reform wave of 1985–1995 fundamentally reshaped the world in which we live.

References

Bates, R H, and A O Krueger (1993), “Generalizations arising from the country studies”, in R H Bates and A O Krueger (eds.), Political and Economic Interactions in Economic Policy Reform: Evidence from Eight Countries, Cambridge: Blackwell.

Bhagwati, J (1978), Anatomy and consequences of exchange control regimes, Cambridge: Ballinger.

Bienen, H (1990), “The politics of trade liberalization in Africa”, Economic Development and Cultural Change 38(4): 713–32.

Collier, P (1993), “Higgledy‐piggledy liberalisation”, World Economy 16(4): 503–11.

Dean, J, S Desai and J Riedel (1994), “Trade policy reform in developing countries since 1985: A review of the evidence”, World Bank Discussion Paper No. 267.

Fernandez, R, and D Rodrik (1991), “Resistance to reform: Status quo bias in the presence of individual-specific uncertainty”, American Economic Review 81(5): 1146–55.

Geddes, B (1994), “Challenging the conventional wisdom”, Journal of Democracy 5(4): 104–18.

Giuliano, P, P Mishra and A Spilimbergo (2013), “Democracy and reforms: Evidence from a new dataset”, American Economic Journal: Macroeconomics 5(4): 179–204.

Irwin, D A (2022), “The trade reform wave of 1985–95”, NBER Working Paper 29973.

Little, I M D, T Scitovsky and M Scott (1970), Industry and trade in some developing countries, London: Oxford University Press for the OECD.

Markoff, J, and V Montecinos (1993), “The ubiquitous rise of economists”, Journal of Public Policy 13(1): 37–68.

Krueger, A O (1978), Liberalization attempts and consequences, Cambridge: Ballinger.

Krueger, A O (1997), “Trade policy and economic development: How we learn”, American Economic Review 87(1): 1–22.

Milner, H V, and K Kubota (2005), “Why the move to free trade? Democracy and trade policy in the developing countries”, International Organization 59(1): 107–43.

Sachs, J D, and A Warner (1995), “Economic reform and the process of global integration”, Brookings Papers on Economic Activity 1: 1–118.

Wacziarg, R, and K H Welch (2008), “Trade liberalization and growth: New evidence”, World Bank Economic Review 22(2): 187–231.

Weymouth, S, and J M MacPherson (2012), “The social construction of policy reform: Economists and trade liberalization around the world”, International Interactions 38(5): 670–702.

Endnotes

1 Sachs and Warner (1995) defined a country as ‘closed’ if it had an average tariff of more than 40%, a nontariff barrier coverage rate of more than 40%, a black-market premium on its currency of more than 20%, a state monopoly on exports, or a socialist economic system. For a general review, see Dean et al. (1994).

2 As Bates and Krueger (1993: 455) conclude from a number of case studies: “One of the most surprising findings is the degree to which interest groups fail to account for the initiation” of economic policy reform.

3 Bienen (1990: 717) observes that “It is striking that African agricultural exporters generally have not been well organized into powerful political groups.” Fernandez and Rodrik (1991) note that potential exporters who will benefit from a reform ex post remain politically inactive because they do not know whether they will benefit ex ante. This explanation is consistent with experience. Many of the reforming countries had significant export potential because policies kept the ratio of exports to GDP artificially low. (To take extreme cases, South Korea’s exports were 1% of GDP in 1960. India’s exports were just 5% of GDP in 1985.) While many producers would become internationally competitive at more realistic exchange rates and access to inputs at world prices, it is almost impossible to know precisely which ones they might be. As a result, producers did not actively press for reforms.

4 In the Uruguay Round negotiations, developing countries reduced bound tariffs, but these were well above applied tariffs (Finger et al. 1996).

5 Countries were reluctant to devalue their currencies, fearing that it would fuel inflation, deteriorate the terms of trade, add to the burden of foreign debt, redistribute income in undesirable ways, and reduce the standard of living of urban workers.

6 Of course, these controls were reinforced by the idea that trade policies should promote industrialization via import substitution. In either case, these import restrictions led some domestic interests – namely, producers competing against imports and importers with preferential access to foreign exchange – to have a stake in ensuring that such policies remained in place, even though those interests were not necessarily the original impetus for them.

7 As Geddes (1994: 113) noted: “In many countries, the biggest, and certainly the most articulate and politically influential, losers from the transition to a more market-oriented economy are government officials, ruling-party cadres, cronies of rulers, and the close allies of all three… [These groups] explain… why many authoritarian governments have had difficulty liberalizing their economies.” In the case of Africa, Bienen (1990: 715) noted: “The most politically powerful pressures for import substitution and/or overvalued exchange rates have come from civil servants, politicians, and the military”, not private businesses.

8 In fact, Giuliano et al. (2013) find that democracies have been more likely to undertake economic reforms than other forms of government.