“The welfare of a nation can scarcely be inferred from a measurement of national income” declared the main inventor of GDP, Simon Kuznets, in 1934. He added in 1962 that “distinctions must be kept in mind between quantity and quality of growth, between its costs and return, and between the short and the long term. Goals for more growth should specify more growth of what and for what”. Decades later, governments and global institutions still rely on GDP as a measure of economic development. While GDP is closely connected to the notion of economic growth, serving as a proxy for the economic muscle of nations, it is only a rough estimate of the capacity of an economy to deliver on the wellbeing of society (Schmidt and Kassenboehmer 2011), ignoring critical aspects related to fairness and sustainability. In the aim of building a fair, sustainable, and prosperous Europe, complementary tools are needed to measure the progress and performance of countries, as well as the ability to transfer wellbeing to future generations (Chancel et al. 2014). The Transitions Performance Index (TPI) developed by the European Commission services contributes to the debate on monitoring sustainability beyond GDP (European Commission 2022).

The growing importance of ‘beyond GDP’ indicators in policymaking

For many years, the notion of economic welfare and wellbeing has been associated with sustained GDP growth. Given the challenges we face – ranging from climate change, growing inequality, accelerated automation and social polarisation to the role of the rule of law – this paradigm should evolve to include social, environmental, and governance aspects, together with the competitive sustainability of our economies. Effective evidence-based decisions require appropriate metrics that help inform policymaking in navigating choices for public investments, directing innovation that benefits all Europeans, creating strategic autonomy, and supporting shared values with global partners.

Although the need to measure economic prosperity ‘beyond GDP’ has long been acknowledged, GDP remains the primary reference metric used by politicians, media, and the public alike. GDP serves a useful purpose in monitoring economic activity. It measures taxable income crucial to provide public services and allows us to compare income levels between countries and their evolution over time through a harmonised, well-known, and publicly accepted indicator. But it does not reflect the full picture (Terzi 2021, Coyle 2016). Its shortfalls have been well-known from the very beginning, including the fact it does not inform policymakers about the distribution of income in a country. In particular, it does not capture natural or social capital, meaning for example that when a forest is cut down and the logs sold, GDP goes up even though the project will aggravate environmental degradation, loss of biodiversity, and climate change. Negative externalities and certain types of public goods, including ecosystem services, are often not priced properly, thus distorting the real image of an economy. More broadly, without complementary indicators, GDP gauges the quantity of economic activity but not its quality. It could therefore provide a distorted picture, failing to illustrate environmental and social sustainability.

In order to gain a greater understanding of policies that promote – or hamper – prosperity, it is essential to expand and improve the dashboard used by policymakers with additional metrics capable of capturing different societal dimensions. Not only can this enrich the public debate on what matters for a sustainable and fair society, it can also make that society more resilient in the face of adversity.

Since the seminal Sen-Stigliz-Fitoussi Report (2009), there have been many initiatives to monitor progress in well-being and sustainability in a more holistic way at both country and regional levels.

The Commission has been an ambitious first-mover on this front, with an initial conference ‘Beyond GDP’ held in 2007 together with the European Parliament, Club of Rome, OECD, and WWF to discuss indices that measure progress and how to integrate them into decision making. The so-called ‘Europe 2020’ strategy’s five measurable EU targets (employment, research and innovation, climate and energy, education, poverty), along with the European Pillar of Social Rights, the European Green Deal, and more recently the Recovery and Resilience Facility, all respond to a ‘beyond GDP’ logic by introducing a range of indicators and targets to assess key dimensions of well-being that include social and environmental aspects. The importance of the UN’s Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) can also be read through this prism, broadening the dashboard that policymakers target when designing new measures for a better society. Moreover, the Commission’s Resilience Dashboards,

published in 2021, provide further forward-looking assessments of vulnerabilities and capacities of the EU and its Member States in four interrelated dimensions: social and economic, green, digital, and geopolitical.

The von der Leyen Commission has recognised the importance of a broad policy agenda that goes well beyond a narrow focus on GDP growth. The Political Guidelines, and later the 2020 Annual Sustainable Growth Strategy (European Commission 2019), see economic growth not as an objective in itself but rather as a means to an end. The fundamental goal is a social, sustainable, and competitive market economy that works for people and for the planet while staying grounded in democratic principles and the rule of law.

A new tool with a more holistic view of progress

To help navigate this complex and multi-faceted policy agenda and to monitor progress along these priorities, the Commission services have developed the Transitions Performance Index (TPI) as a new dashboard (European Commission 2022).

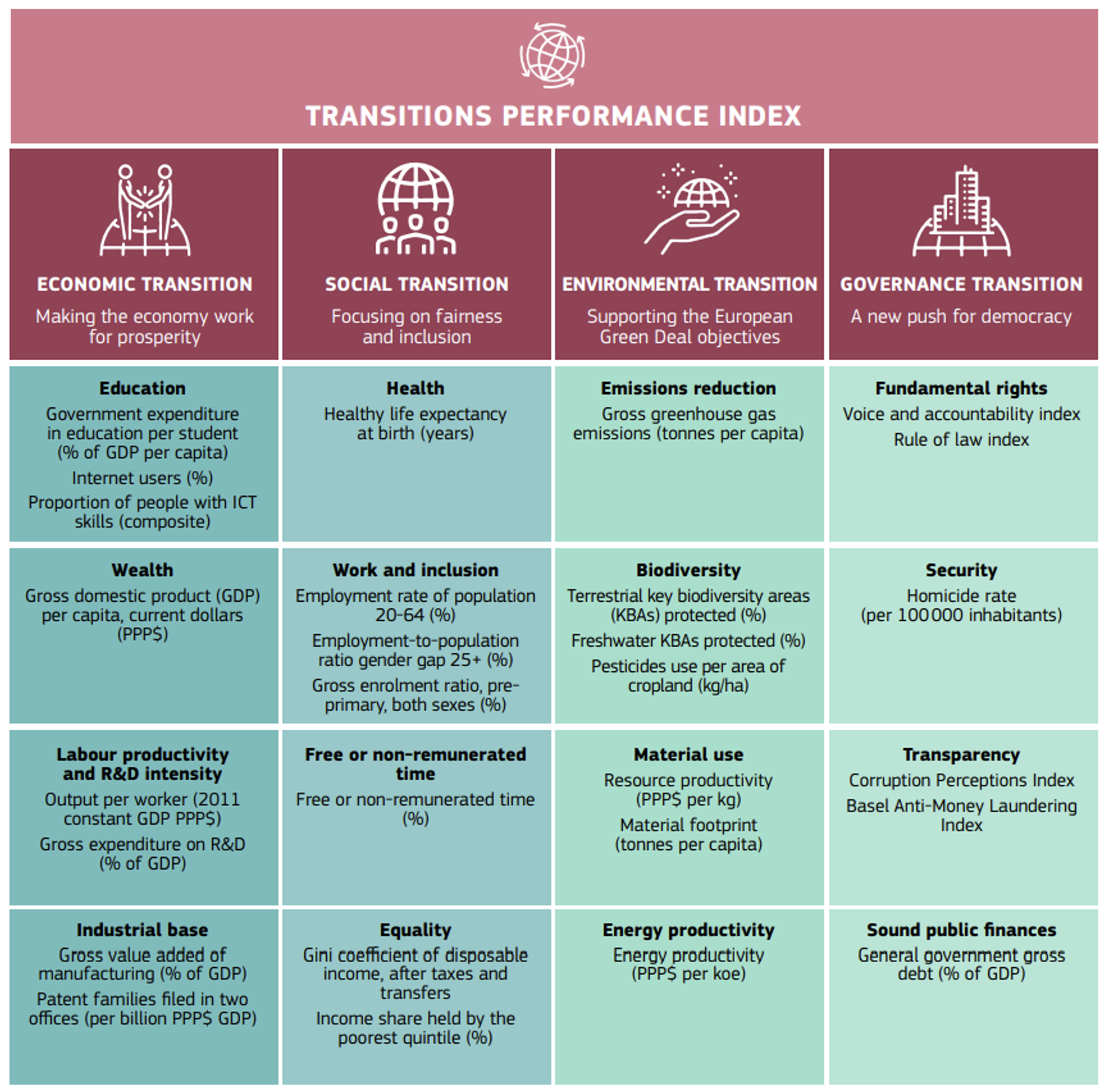

The TPI is both a scoreboard and a composite indicator that monitors and ranks countries based on their transitions towards fair and prosperous sustainability. It shows overall performance in four specific transitions – economic, social, environmental, and governance – as well as 16 sub-pillars (see Figure 1). Some sub-pillars focus on opportunity (education, work, inclusion), others on resilience (health, fundamental rights), still others on prosperity (wealth, non-remunerated time) or intergenerational fairness (emissions reduction, sound public finances, material footprint, biodiversity).

Figure 1 TPI conceptual framework and indicators

The TPI illustrates the contributions of each transition to the overall performance of a country over time, indicating strengths and weaknesses, room for progress, trade-offs, and synergies. It scores and ranks the EU27 Member States as well as 45 other countries, covering 76% of the world’s population.

In its second and most recent edition, published in March 2022, the index has evolved to better mirror green and digital transitions, with two additional indicators capturing the increasing role of digitalisation, and one indicator to track a country’s material footprint. This new edition points to strong performances from all Member States, most notably Denmark and Ireland, second and third in the global ranking behind Switzerland. Even among top achievers, there remains significant scope for improvement, as no country leads across all four dimensions. In addition, for half of the indicators, no country reaches the maximum normalised score.

Data analysis from the previous ten years is included in the latest TPI report. This allows us to assess long-term trends and to highlight the role of these trends in the concept of transitions. This is of great value, as many of these transition dynamics are slow moving. The index confirms that almost all EU countries have progressed well over the last decade, with an average rate of improvement in the index of 4.9% compared to the global average rate of 4.3%. However, there are great disparities between countries and between pillars and sub-pillars for a given country.

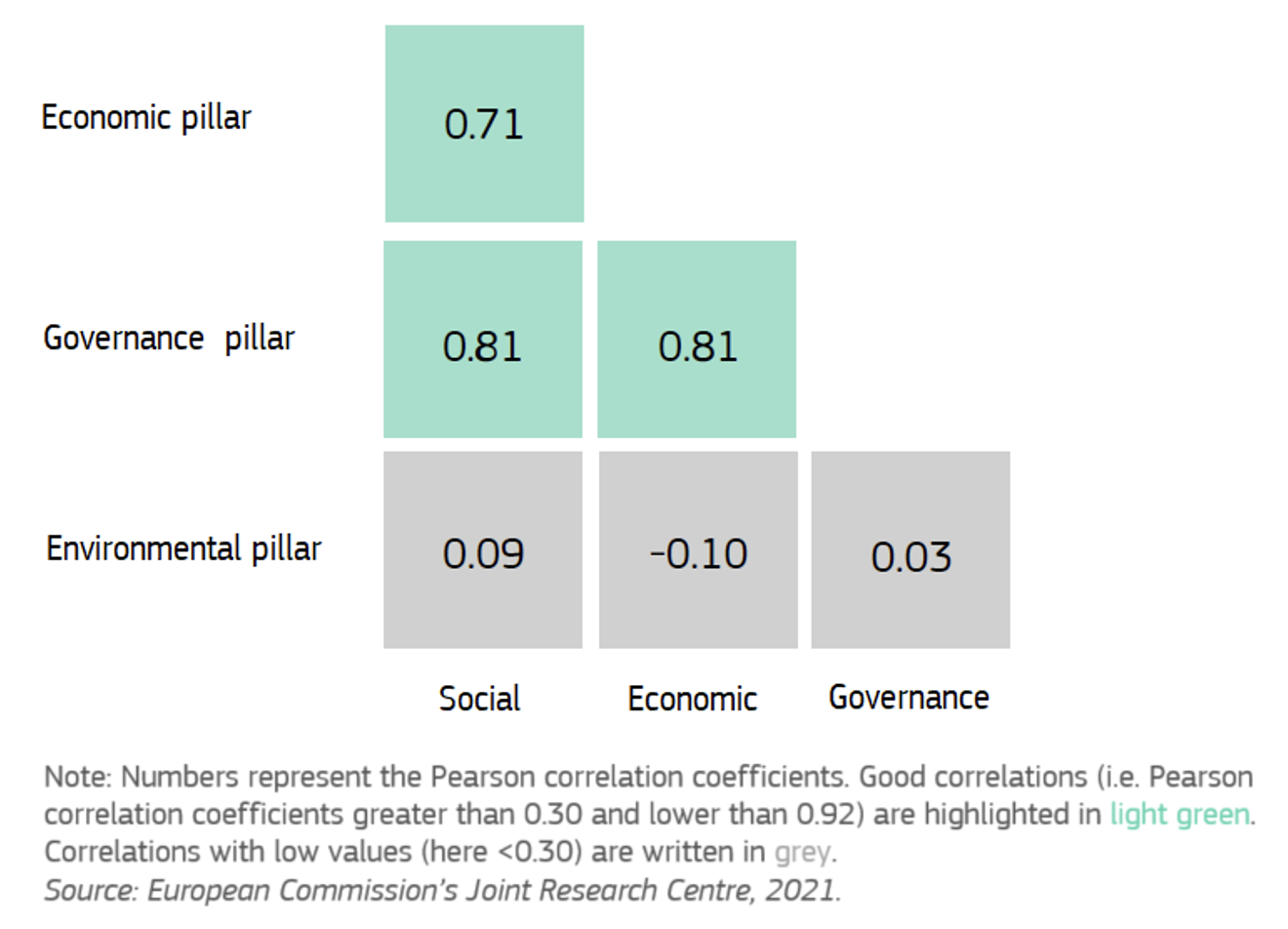

An important finding of the TPI is that most countries have not yet ‘bent their curves’ towards the green transition, meaning that they are not yet on a sustainable path of decreasing emissions and material use and restoring biodiversity. The weak correlations between the environmental pillar and the other pillars show the challenge of finding a path toward a prosperous and sustainable society (Figure 2).

Figure 2 Correlations between the pillars

These issues will come increasingly to the fore for developing and emerging economies, which currently perform well in the environmental dimension of the TPI but are naturally looking to further industrialise. Such economic development could hamper the progress under the environmental pillar unless it is guided by ‘green development’ principles (Hausmann 2021).

In addition to indicators for the green transition, the index points to the key role in transition performance of education, gender equality, and fairness (equality). By increasing the efficiency and adaptability of economic and social systems, Research and Innovation contribute to progress in the transitions measured by the TPI. The TPI report also highlights the crucial role of good governance as an important pillar to achieve resilient, inclusive, and sustainable growth. Worryingly, around 1.6 billion people live in countries where the governance score decreased.

The TPI shows the feasibility of measuring progress towards all dimensions of sustainability with a limited number of indicators. It complements other monitoring tools already available, including the Eurostat SDG indicator set, Recovery and Resilience Scoreboard, Resilience Dashboards, or the European Pillar of Social Rights. Looking ahead, it opens avenues for further research into the determinants of performance and the ability to progress towards fair and sustainable prosperity, going beyond the conventional measurement of GDP.

Authors’ note: The views expressed here are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of the European Commission.

References

Chancel, L, G Thiry and D Demailly (2014), “Beyond-GDP indicators: to what end?”, Study N°04/14, IDDRI, Paris.

Coyle, D (2016), GDP: A Brief Affectionate History, Princeton University Press.

European Commission (2019), Annual Sustainable Growth Strategy 2020, SWD(2019) 444.

European Commission (2020), “Strategic Foresight Report, Charting the course towards a more resilient Europe”.

European Commission (2022), “Transitions performance index 2021: towards fair and prosperous sustainability”, Directorate-General for Research and Innovation.

Hausmann, R (2021), “Is Green Development an Oxymoron?”, Project Syndicate, 1 June.

Manca, A, P Benczur and E Giovannini (2017), “Building a Scientific Narrative Towards a More Resilient EU Society Part 1: a Conceptual Framework”, EUR 28548 EN, Luxembourg: Publications Office of the European Union, JRC106265.

OECD (2020), How's Life? 2020: Measuring Well-being, OECD Publishing, Paris.

Schmidt, C and S Kassenboehmer (2011), “Beyond GDP and Back: What is the Value-added by Additional Components of Welfare Measurement?”, CEPR Discussion Paper No. 8225.

Stiglitz, J E, A Sen and J P Fitoussi (2009), Report by the Commission on the Measurement of Economic Performance and Social Progress.

Terzi, A (2021), “Economic Policy-Making Beyond GDP: An Introduction”, No. 142, Directorate General Economic and Financial Affairs (DG ECFIN), European Commission.