The US dollar is used extensively globally to finance international trade and financial transactions, as recently detailed by the ECB (2022) and Goldberg et al. (2022). This prevalence is reflected in the 2019 data on foreign exchange and derivatives transactions (BIS 2019) and the large volumes of dollar funding flows through varied intermediaries and market instruments detailed in the BIS CGFS (2020) report, US Dollar Funding: an International Perspective. Intermediaries that might provide US dollars through one instrument, for example a loan, also need to fund that asset by borrowing US dollars, for example through US dollar deposits. The global interconnectedness of markets can quickly transmit both favourable conditions and strains across financial markets and institutions as illustrated by the interactive mapping of US dollar funding flows in Afonso et al. (2019). Frictions and perhaps preferences mean that dollar transactions still occur at premium conditions, sometimes reflected in deviations from covered interest rate parity (Du et al. 2018).

Under normal conditions, the broad participation and high volume of activity in global US dollar funding markets means that borrowers incur relatively low funding costs. International capital flows and global dollar liquidity respond relatively smoothly to changes in risk and returns across markets, without an excessive price impact. When conditions are stressed, price dispersion occurs, as gaps widen between the cost of funds for some market participants and the price other market participants are willing to pay. Global liquidity flows, the more volatile part of international capital flows, can retrench and redirect, particularly as global banks and financial institutions realign and redeploy scarce funds via their internal capital markets. Against this backdrop, in recent crises the Federal Reserve (FOMC), along with other central banks, deployed international dollar liquidity backstops to alleviate those strains globally and prevent spillback to the US.

Global dollar funding and the backstop role of international dollar facilities

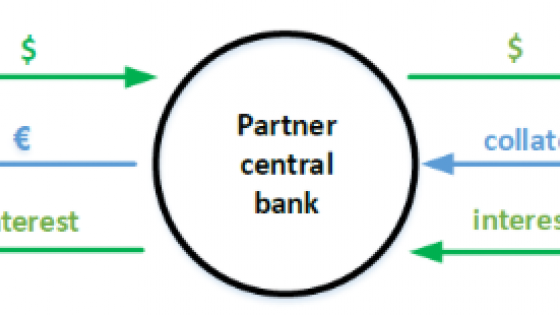

Currently, the Fed has two complementary international dollar liquidity facilities: the central bank swap lines (CB dollar swaps) and the Foreign and International Monetary Authorities (FIMA) repo facility. These facilities are priced as a ‘backstop’ to help ensure that the facility is used largely in times of acute and systemic stress, and not as a replacement for private markets in normal times. The current structure builds on lessons from historical constructs, as detailed in McCauley and Schenk (2020).

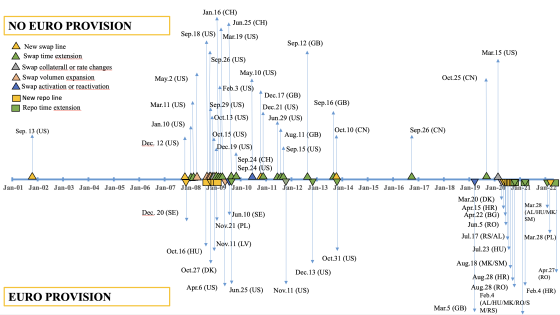

During the global crisis in 2007-2008, temporary central bank dollar swaps were deployed, providing US dollar liquidity to 14 different central banks to help smooth strains in global US dollar funding markets (Goldberg et al. 2011, Bahaj and Reis 2018).

Central bank dollar swaps were redeployed in 2010 at the onset of the euro area sovereign and banking crisis and given their effectiveness as an international dollar liquidity backstop were subsequently converted into ‘standing facilities’ in October 2013.

Following the outbreak of Covid-19, the swap lines were enhanced again to help alleviate stresses in global dollar funding markets (Cetorelli et al. 2020a, Liao and Zhang 2020, Albrizio et al. 2021, and Choi et al. 2022).

The FIMA repo facility was established at the outbreak of the Covid-19 pandemic on 31 March 2020, to support the smooth functioning of the US Treasury market by providing reassurance to FIMA account holders of their ability to secure dollar liquidity through repo transactions with the Fed in times of unusual market strains, rather than through selling their US Treasury securities or financing US Treasury securities in the private repo market.

The pandemic and the international dollar facilities’ effects on global markets and credit

After the pandemic onset in March 2020, central bank dollar swaps and the Foreign and International Monetary Authorities (FIMA) repo facility affected conditions in global dollar funding markets and supported the continuation of credit flows globally and in the US (Ferrara et al. 2022, Yun 2021, and Cetorelli et al. 2020b). In a recent research paper (Goldberg and Ravazzolo 2022) we find that the effects appears to be concentrated in the first half of 2020, also covering foreign country US Treasury holdings, official foreign reserve positions, bank-based credit and liabilities, and global portfolio.

The cost of dollar liquidity and its sensitivity to risk sentiment

During the very early period of the pandemic, the settlement of dollars demanded at the Fed’s standing swap lines operations calmed funding strains, even more than the announcement of facilities (Cetorelli et al. 2020a, Persi 2020). Country access to the Fed’s international dollar liquidity facilities is associated with reduced costs of borrowing dollars locally in the foreign exchange (FX) swap market, initially only for countries of central banks with access to standing or temporary swap lines (SSCBs or TSCBs) and later also for countries without swap lines but with access to the FIMA repo facility (Others) (Goldberg and Ravazzolo 2022).

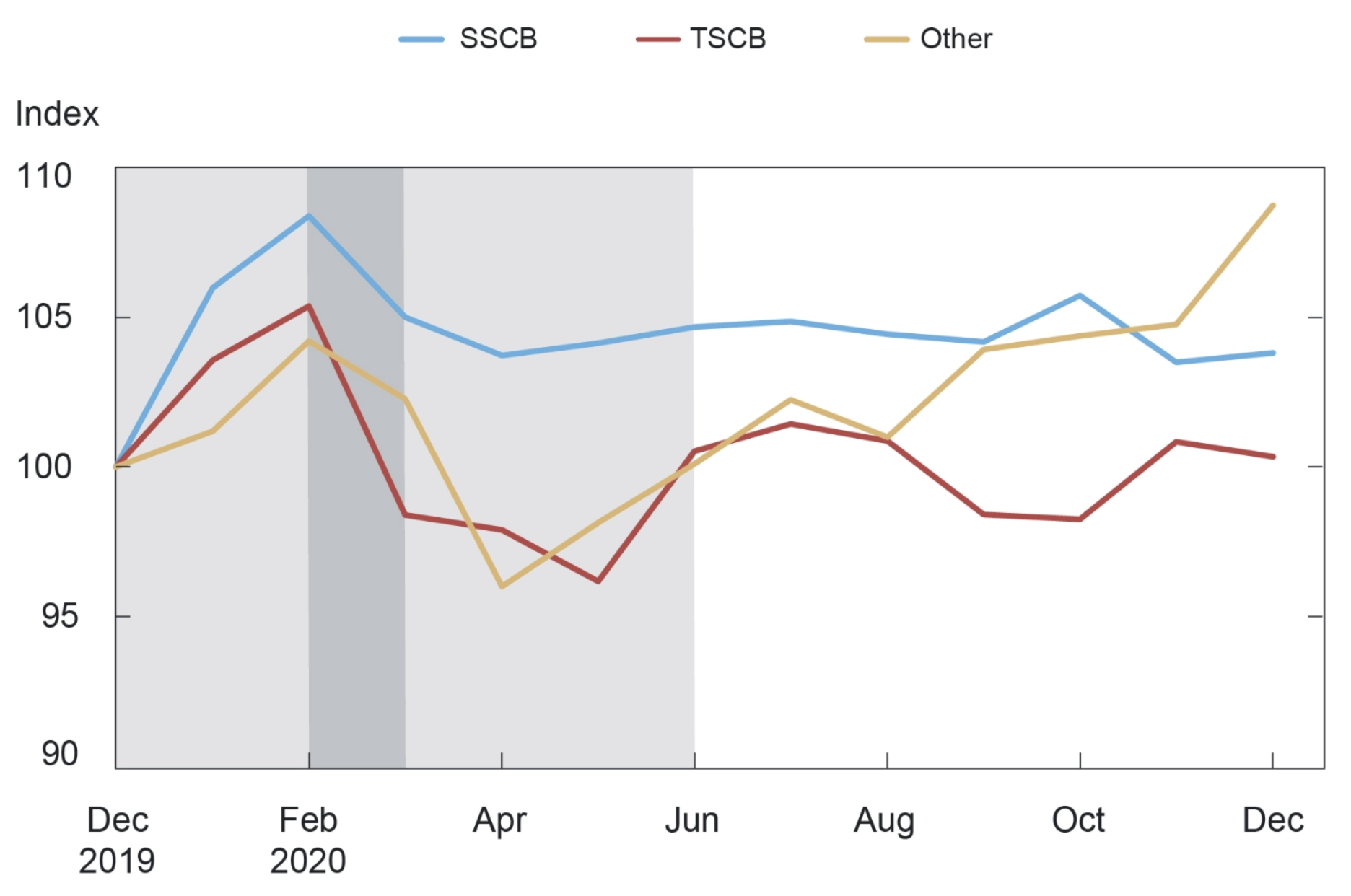

The average foreign exchange swap basis spreads of currencies, indicating the marginal cost of obtaining dollar funding offshore relative to borrowing in onshore funding markets, increased in the initial stress period (Figure 1, dark grey area) compared to the pre-pandemic period. The currencies of countries with access to swap lines (SSCBs and TSCBs) stabilised quicker than those without (that is, the ‘Other’ countries), although relatively less liquid trading conditions in ‘Other’ countries may have initially amplified strains in their local dollar funding markets. After the activation of the FIMA repo accounts, currencies of ‘Other’ countries had large declines in dollar funding strains, despite minimal aggregate usage of the FIMA repo facility in the spring of 2020 (right light grey area in the chart). While dollar funding conditions for SSCB countries returned to pre-pandemic levels, the experiences of TSCB and ‘Other’ countries remained more differentiated. For all countries with access to swap lines or the FIMA repo facility, analytics show there was also a reduced sensitivity of the dollar funding strains to changes in risk sentiment.

Figure 1 Foreign exchange swap basis spreads stabilise following Fed actions

Sources: Bloomberg; authors’ calculations.

Notes: Data are as of 11 a.m., London time, and are based on overnight unsecured funding rates (OIS) along with bilateral spot and forward exchange rates with three-month tenors. A positive number reflects a premium to borrow or hedge US dollars. SSCB and TSCB refer to countries of central banks with access to standing and temporary swap lines, respectively. ‘Other’ refers to countries without swap lines but with FIMA repo facility access. Lines represent group simple averages of the basis spreads over currencies in SSCB, TSCB, and Other countries, and shadow area periods are defined in Goldberg and Ravazzolo (2022).

The quantity of global dollar liquidity

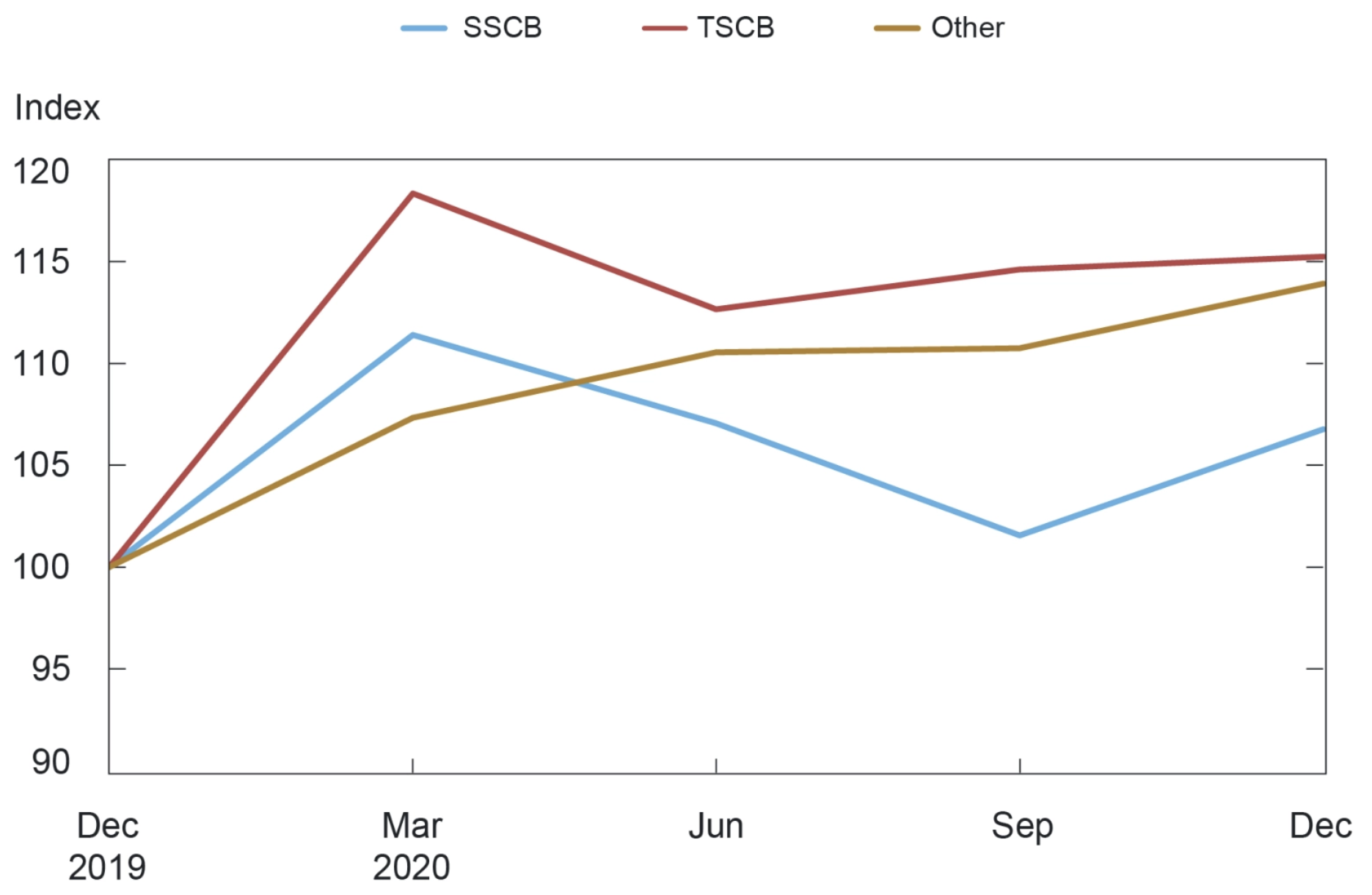

At the outbreak of the pandemic in March 2020, some countries liquidated stocks of foreign currency reserves and reduced US Treasury holdings to raise dollar liquidity to build precautionary buffers, to support the dollar funding needs of local institutions, and for central bank official interventions in foreign exchange markets. In Goldberg and Ravazzolo (2022), we find that official reserve balances of countries without swap lines declined on average in the spring of 2020 and reverted back only after the establishment of FIMA repo facility access. Foreign entities, including private investors, from countries with access only to temporary facilities (the TSCB or the FIMA repo) on average reduced US Treasury holdings early in the pandemic (Figure 2, dark grey band), with further reductions occurring in April and May 2020 for countries without swap lines.

Figure 2 US Treasury holdings of foreign countries

Sources: US Treasury Department; authors’ calculations.

Notes: SSCB and TSCB refer to countries of central banks with access to standing and temporary swap lines, respectively. ‘Other’ refers to countries without swap lines but with FIMA repo facility access. Monthly series are indexed to 100 using December 2019 values. Shaded areas are explained in the Goldberg and Ravazzolo (2022).

During the pandemic, the swap lines and the FIMA repo facility potentially supported credit provision in the US and abroad. Using Bank for International Settlements International Banking Statistics, we find that cross-border banking flows did not collapse in the aftermath of the pandemic shock, a sharp departure from patterns in the global crisis. Specifically, Figure 3 shows the cross-border banking liabilities of the specific countries in the respective groupings, with increases indicating greater credit provision by banks. The figure indicates that credit provision went mostly to bank and nonbank borrowers in countries with access to swap lines.

Interestingly, the gap between countries with SSCB or TSCB access and ‘Other’ countries closed in the later period, and after the FIMA repo accounts were established, as the surge of liabilities of banks in SSCB countries somewhat reverted and banks in ‘Other’ countries had further increases in inflows. Despite the minimal usage of this facility, it helped increase central banks’ confidence in their ability to raise dollar liquidity through the facility, and likely contributed to a strong and quick return to Treasury investment (Weiss 2022). We find that bond fund flows were stable across countries and quickly reverted back or expanded beyond pre-pandemic levels by June 2020. In contrast, global equity portfolio inflows for all countries sharply contracted in March 2020 and remained depressed through summer 2020.

Figure 3 Cross-border liabilities (non-US bank sector)

Sources: Bank for International Settlements, authors’ calculations.

Notes: SSCB and TSCB refer to countries of central banks with access to standing and temporary swap lines, respectively. ‘Other’ refers to countries without swap lines but with FIMA repo facility access. Quarterly series are indexed to 100 using 2019:Q4 values.

Summing up

After the outbreak of the pandemic, the Fed’s international dollar facilities helped stabilise market conditions and increased credit provision globally in a very short time, particularly in countries with access to the standing swap lines. Our research shows that when facilities were in place and accessible as backstops, they generally helped reduce the sensitivity to risk of offshore dollar funding costs. Access to the different types of Fed international dollar facilities also mattered for the speed and degree of normalisation of conditions in offshore dollar funding markets. Finally, continuation of cross-border lending through banks to countries appears to be associated with access to the Fed facilities.

Authors’ Note: The views are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of the Federal Reserve Bank of New York or Federal Reserve System.

References

Afonso, G, F Ravazzolo and A Zori (2019), “From Policy Rates to Market Rates—Untangling the U.S. Dollar Funding Market”, Federal Reserve Bank of New York Liberty Street Economics, 8 July.

Albrizio, S, I Kataryniuk, L Molina Sanchez and J Schaefer (2021), “The effectiveness of ECB euro liquidity lines”, VoxEU.org, 29 September.

Bahaj, S and R Reis (2018), “Central bank swap lines”, VoxEU.org, 25 September.

Bank of International Settlement (2019), “Triennial Central Bank Survey of Foreign Exchange and Over-the-counter (OTC) Derivatives Markets in 2019”, Triennial Central Bank Survey, 8 December.

Bank of International Settlement (2020), “US Dollar Funding: an International Perspective”, Committee of Global Financial System papers, No 65, 18 June.

Cetorelli, N, L S Goldberg and F Ravazzolo (2020a), “Have the Fed Swap Lines Reduced Dollar Funding Strains during the COVID-19 Outbreak?”, Federal Reserve Bank of New York Liberty Street Economics, 22 May.

Cetorelli, N, L S Goldberg and F Ravazzolo (2020b), “How Fed Swap Lines Supported the U.S. Corporate Credit Market amid COVID-19 Strains”, Federal Reserve Bank of New York Liberty Street Economics, 12 June.

Choi, M, L S Goldberg, R Lerman and F Ravazzolo (2022), “The Fed's Central Bank Swap Lines and FIMA Repo Facility”, Federal Reserve Bank of New York Economic Policy Review 28(1): 93-113.

Du, W, A Tepper and A Verdelhan (2018), “Deviations from Covered Interest Rate Parity”, Journal of Finance 73(3): 915-957.

European Central Bank (2022), “The international role of the euro”, 21st annual review of the international role of the euro, June.

Ferrara, G, P Mueller, G Viswanath-Natraj and J Wang (2022), “Central Bank Swap Lines: Micro-Level Evidence”, Bank of England Staff Working Paper No 977, 6 May.

Goldberg, L S, C Kennedy and J Miu (2011), “Central Bank Dollar Swap Lines and Overseas Dollar Funding Costs”, Federal Reserve Bank of New York Economic Policy Review, May.

Goldberg, L S, R Lerman and D Reichgott (2022), “The U.S. Dollar’s Global Roles: Revisiting Where Things Stand”, Federal Reserve Bank of New York Liberty Street Economics, 5 July.

Goldberg, L S and F Ravazzolo (2022), “The Fed's International Dollar Liquidity Facilities: New Evidence on Effects”, CEPR Discussion Paper no DP17233, May.

Liao, G and T Zhang (2020), “Currency hedging, exchange rate movement, and dollar swap line usage during Covid-19”, VoxEU.org, 01 October.

McCauley, R and C Schenk (2020), “Swap innovation, then and now”, VoxEU.org, 12 April.

Persi, G (2020), “US dollar funding tensions and central bank swap lines during the COVID-19 crisis”, European Central Bank, Economic Bulletin Issue No 5, 30 July.

Weiss, C R (2022), "Foreign Demand for U.S. Treasury Securities during the Pandemic," FEDS Notes, Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System, 28 January.

Yun, Y (2021), “International spillover of central bank swap lines - Evidence from the COVID-19 experience of Korea”, Finance Research Letters 43, November.