Isabel Schnabel (2022), Executive Board member of the European Central Bank (ECB), recently argued that: “Our currencies are stable because people trust that we will preserve their purchasing power. For politically independent central banks, establishing and maintaining that trust is an important policy objective in and of itself. Failing to honour this trust may carry large political costs.” Nonetheless, during 2022 inflation has increased strongly to levels as high as 10%. Even though the current inflation is driven largely by factors outside of central banks’ control, they risk losing trust and credibility due to this strong uptick in inflation. Already at the start of the uprise of inflation, 41% of respondents in the Eurobarometer survey mentioned prices, inflation, cost of living (an increase of 18 percentage points compared to the previous survey) as one of the most important issues facing their country, before health (32%) and the economic situation (19%).

Losing trust will make it harder for central banks to bring inflation back to target. Several studies report that inflation expectations of individuals who trust central banks tend to be closer to the central bank’s inflation target (Christelis et al. 2020, Rumler and Valderama 2020, van der Cruijsen and Samarina 2021, Brouwer and de Haan 2022). Furthermore, Stanisławska and Paloviita (2021) find that individuals who trust the central bank adjust their inflation expectations less in response to transitory economic developments than individuals who distrust the central bank.

Despite the importance of trust in central banks, little is known about the impact of the recent high inflation levels on public trust in the ECB. Using a new survey among more than 2,000 individuals in the Netherlands, we have examined to what extent the recent surge in inflation has affected trust in the ECB (van der Cruijsen et al. 2023). It is well-known that knowledge about actual inflation of survey respondents is often wrong (Christelis et al. 2020). We hypothesise that the higher respondents’ inflation perceptions are, the lower their trust in the ECB. We also analyse the relationship between the extent to which respondents have been personally hit by the recent inflation and their trust in the ECB. We hypothesise that respondents who have more difficulties to make ends meet or are otherwise affected by increased inflation have lower trust in the ECB. Finally, we explore the relationship between respondents’ trust in the ECB and their views on who is responsible for bringing inflation down. Academics consider the central bank as being responsible for maintaining price stability, but as we will show, many respondents in our survey think this is a responsibility of national politics. We hypothesise that trust in the ECB is negatively related to whether respondents consider the ECB responsible for bringing inflation down.

We use the DNB Trust Survey (DTS) and an additional survey among the Centerpanel to collect data on public trust of Dutch households. This database can be linked to data from the DNB Household Survey (DHS), which provides detailed information on respondents’ characteristics, such as their education level, gender, financial literacy, and employment situation for which we can control.

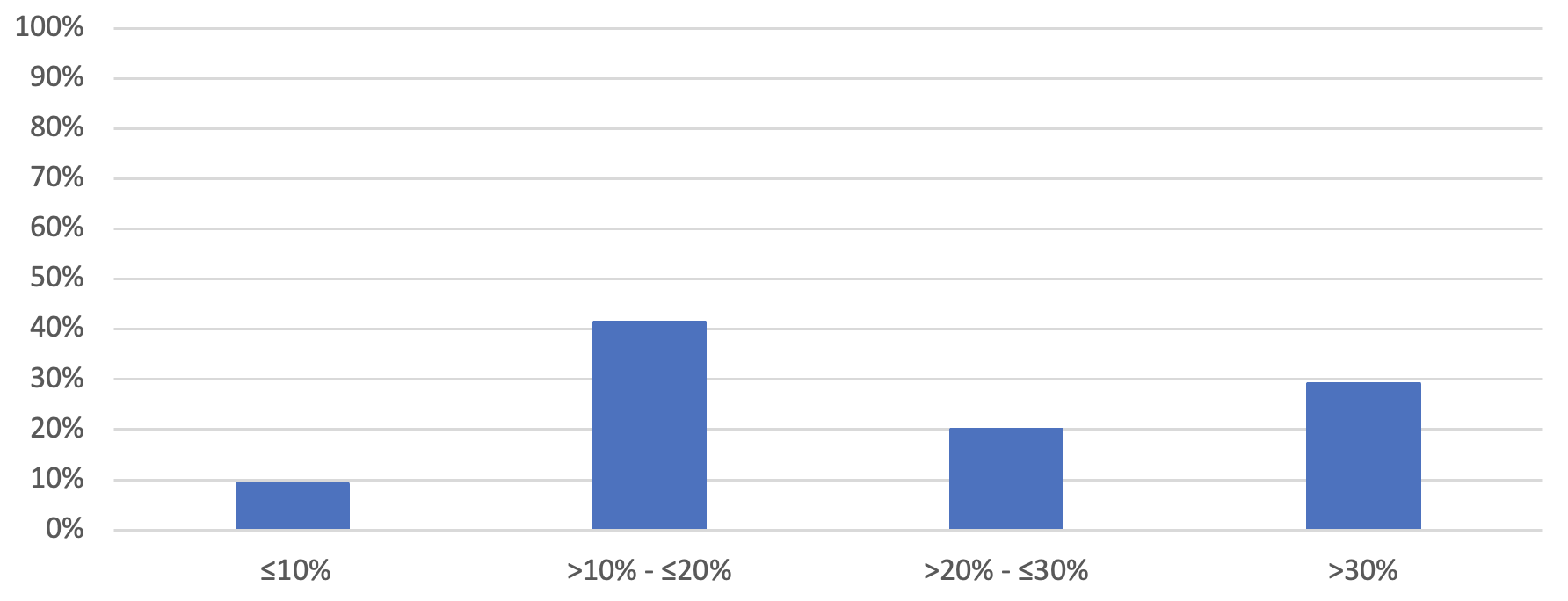

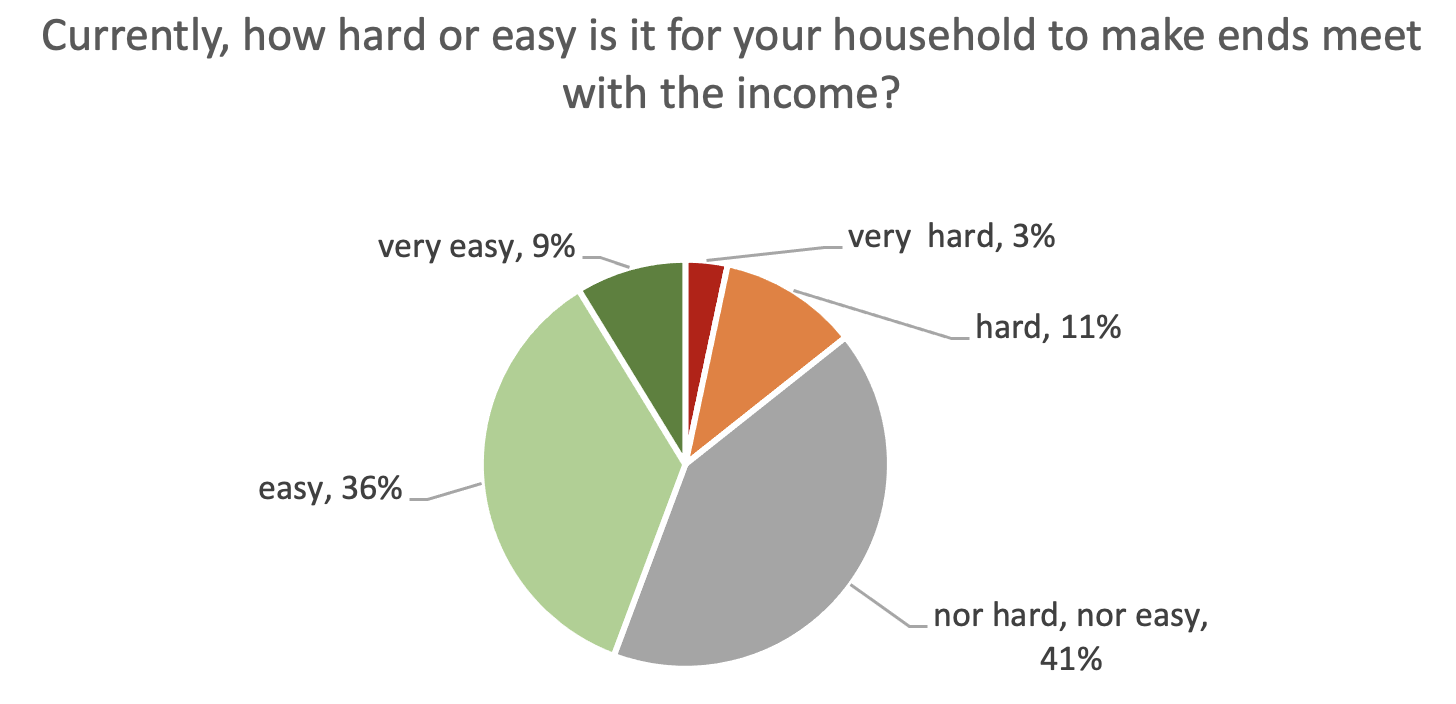

The perceived level of inflation differs quite substantially among respondents as shown in Figure 1. In fact, 49% of the people think that inflation is above 20%. The level of inflation shown in this figure is distilled from respondents’ answers to the question: “Suppose that 12 months ago you had to pay 100 euro for your groceries at the supermarket. How much do you think you need to pay now for the same groceries in the same supermarket?” Price increases may lead to a loss in purchasing power and cause financial difficulties. As Figure 2 shows, many individuals indeed find it hard to make ends meet. An additional question probing how increased prices affect respondents personally shows that the effect of the rise in inflation goes beyond the financial impact of price increases. For instance, 20% of the individuals experience more stress as a result of inflation.

Figure 1 Respondents’ perceived level of inflation

Source: Centerpanel September/October 2022.

Note: The answers of 2,464 respondents have been weighted to correct for differences between the sample and the population with respect to gender, age, net household income, and the level of education.

Figure 2 Respondents’ views on how hard it is to make ends meet

Source: Centerpanel September/October 2022.

Note: The answers of 2,464 respondents have been weighted to correct for differences between the sample and the population with respect to gender, age, net household income, and the level of education.

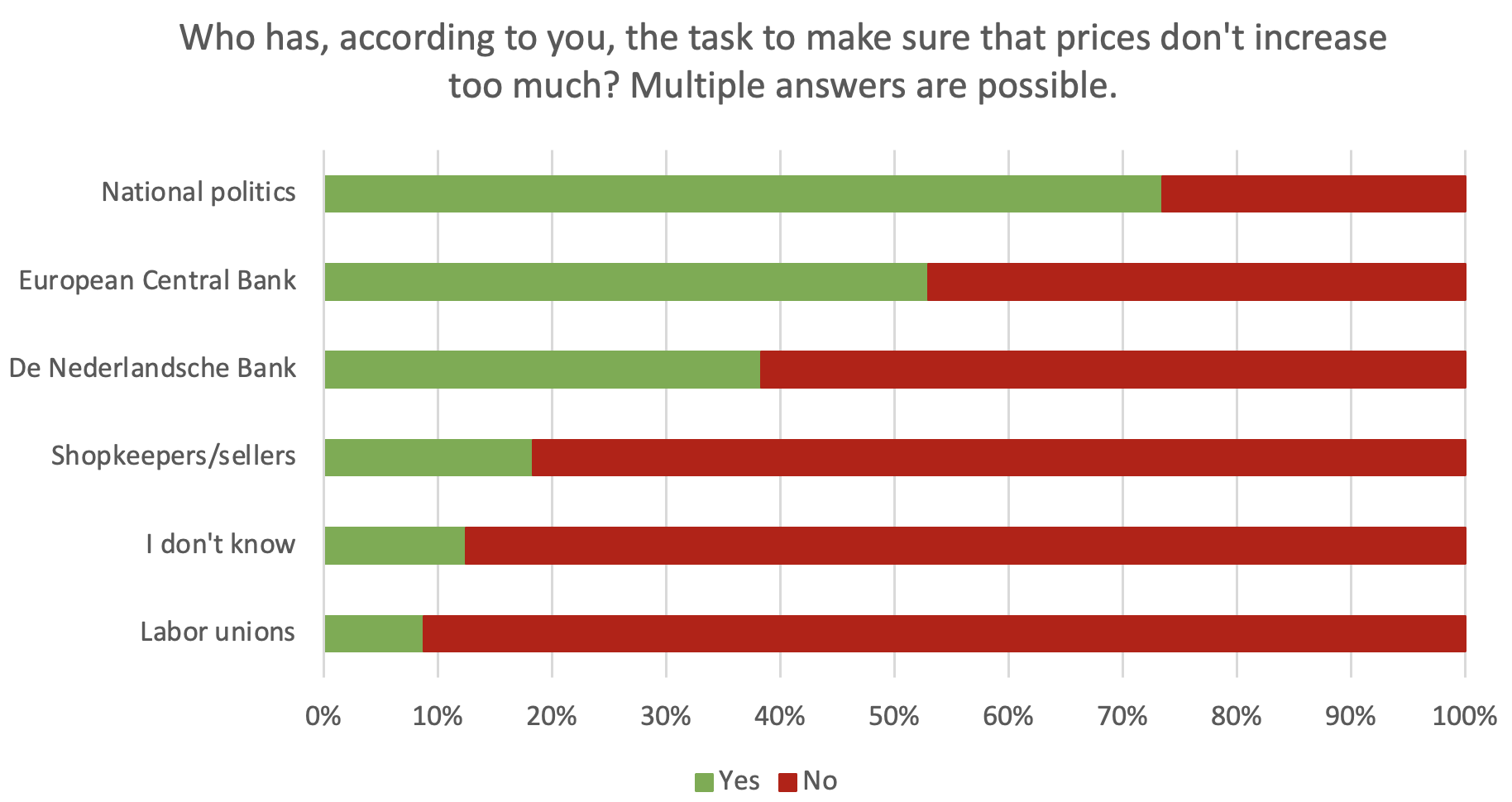

Finally, as shown in Figure 3, it is quite remarkable that more than seven out of ten people think that national politics has the task to prevent high inflation, while slightly more than half of them (also) tick the ECB in answering this question.

Figure 3 Respondents’ views on who has the task to prevent high inflation

Source: Centerpanel September/October 2022.

Note: The answers of 2,464 respondents have been weighted to correct for differences between the sample and the population with respect to gender, age, net household income, and the level of education.

We have estimated ordered logit models to examine whether there is a positive association between perceived inflation and public trust in the ECB. The dependent variable is an ordered variable capturing trust in the ECB on a scale between 1 and 4 (1 = absolutely no trust, 2 = not so much trust, 3 = pretty much trust, 4 = a lot of trust). We control for several characteristics of respondents that previous studies found to be related to trust (see van der Cruijsen et al. 2023 for details). Our results suggest that there is a negative relationship between perceived inflation and public trust in the ECB. The higher individuals’ perceived inflation, the lower their trust in the central bank. To be more precise, individuals with inflation perceptions higher than 30% are 24 percentage points less likely to have a fair amount or a lot of trust in the ECB.

Ordered logit models have also been used to test the hypothesis that respondents who are most affected by price increases have lower trust in the ECB. We test this hypothesis in two ways. First, we include information on whether households can make ends meet. Our estimates show that individuals who find it harder to make ends meet have lower trust in the ECB. To be more precise: members of households who find it very hard to make ends meet are 45 percentage points less likely to have a fair amount or a lot of trust in the ECB than members of households who find it very easy to make ends meet.

Second, we include information on households’ financial positions. The results show a strong association between trust in the ECB and national politics and households’ current financial situation. Individuals belonging to households that incur debt or have to use their savings report significantly lower trust levels than individuals belonging to households that still have money left over. For instance, individuals of households that incur debt are 34 percentage points less likely to have a fair amount or a lot of trust in the ECB than individuals of households that have a lot of money left over.

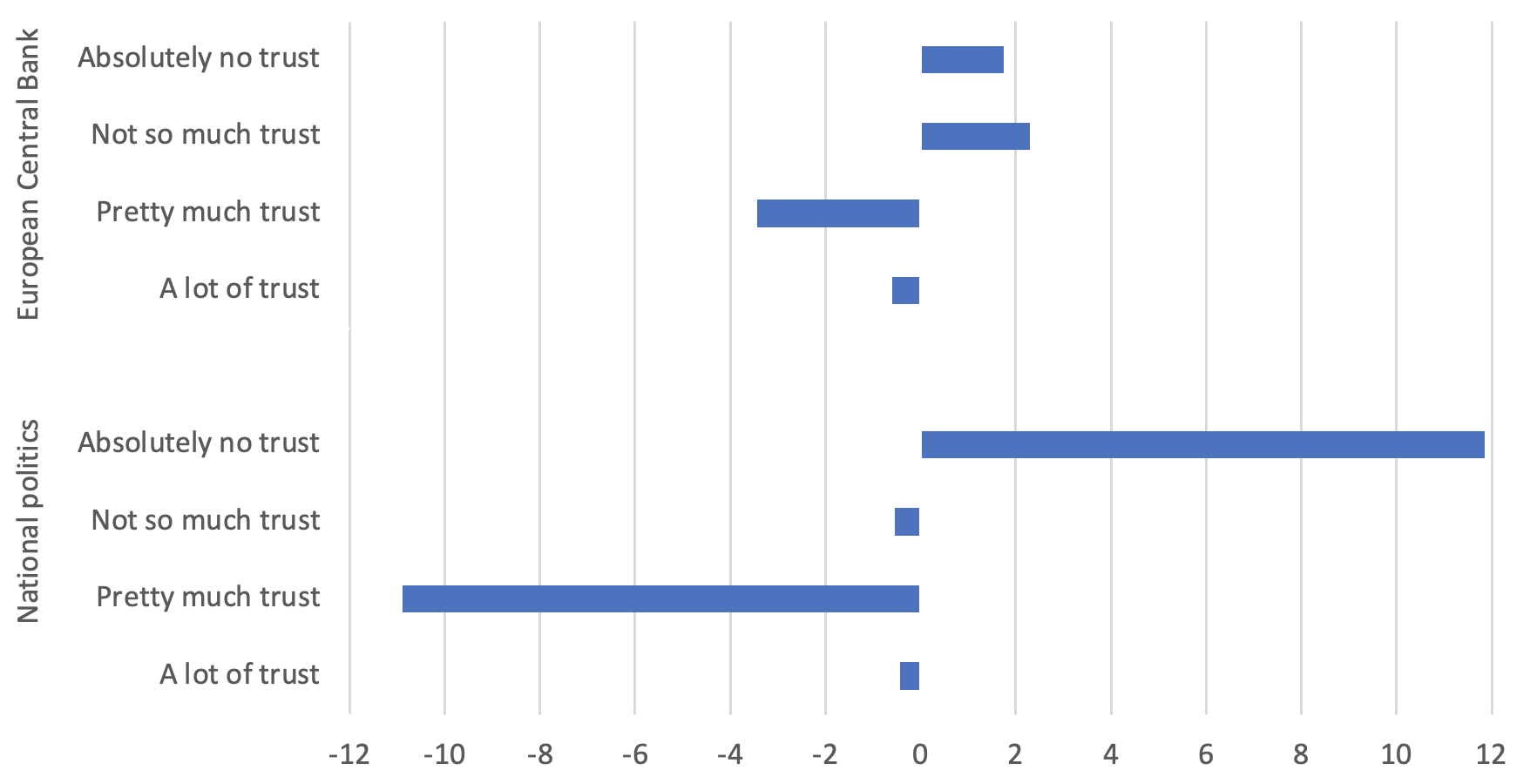

Finally, we have tested the hypothesis that trust is related to whether individuals consider the ECB responsible for bringing inflation down. To investigate this hypothesis, we include a dummy variable measuring whether respondents consider the ECB responsible for preventing high inflation in an ordered logit regression that simultaneously includes the information on perceived inflation and on whether households can make ends meet. Similar regressions investigate whether respondents who consider the government responsible for bringing inflation down report lower trust in national politics. We find a negative relationship between public trust and individuals’ views on which authority they hold responsible for price stability. For example, individuals who hold the ECB responsible for price stability are four percentage points less likely to have a fair amount or a lot of trust in the ECB than individuals who do not think the ECB has the task to prevent high inflation (see Figure 4). For national politics the impact is even stronger and equals 11 percentage points.

Figure 4 Average marginal effects of holding an authority responsible for price stability (in percentage points)

In conclusion, our results suggest that the higher people’s perceived inflation and the harder they find it to make ends meet, the lower their trust in the ECB. Trust in the ECB is relatively low for those individuals who believe the ECB has the task to keep inflation low. It is quite remarkable that more than seven out of ten people think it is the task of the government to keep inflation low. This suggests that the conclusion of Blinder et al. (2022) that in their outreach to the general public central banks should focus on their mandate also holds for the ECB.

Authors’ note: The views expressed here are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the views of De Nederlandsche Bank or the Eurosystem.

References

Blinder, A S, M Ehrmann, J de Haan and D Jansen (2022), “Central bank communication with the general public: Promise or false hope?”, NBER Working Paper 30277.

Brouwer, N and J de Haan (2022), “Trust in the ECB: Drivers and Consequences”, European Journal of Political Economy 74, 102262.

Christelis, D, D Georgarakos, T Jappelli and M van Rooij (2020), “Trust in the central bank and inflation expectations”, International Journal of Central Banking 16(6): 1-37.

Rumler, F and M T Valderrama (2020), “Inflation literacy and inflation expectations: Evidence from Austrian household survey data”, Economic Modelling 87: 8–23.

Schnabel, I (2022), “Monetary policy and the Great Volatility”, speech at the Jackson Hole Economic Policy Symposium organized by the Federal Reserve Bank of Kansas City, Jackson Hole, Wyoming.

Stanisławska, E and M Paloviita (2021), “Medium- vs. short-term consumer inflation expectations: Evidence from a new Euro Area survey”, Narodowy Bank Polski Working Paper 338.

van der Cruijsen, C, J de Haan and M van Rooij (2023), “The impact of high inflation on trust in national politics and central banks”, DNB Working Paper, forthcoming.

van der Cruijsen, C and A Samarina (2021), “Trust in the ECB during the pandemic”, VoxEU.org, 3 October.