There are multiple channels through which conflict and institutional instability can affect relevant economic variables. The most direct economic effects of armed conflict and protests occur when these result in the physical destruction of private property (Johnson et al. 2002, Besley and Mueller 2018) or human capital, and in distortions of trade and financial flows. The mere risk of conflict escalation can indirectly generate similar results by influencing market expectations and changing asset prices, investment and hiring strategies, and other otherwise standard strategies of households and firms (Zussman and Zussman 2006, Besley and Mueller 2012). Expectations are also precisely what is affected by uncertainty regarding the future course of economic and general government policy (Bloom 2009, Baker et al. 2016), and can in some cases even lead to firms modifying their behaviour in an attempt to influence that policy (Hassan et al. 2019). Institutional quality is a significant factor affecting the behaviour of both foreign and domestic investors: countries with better governance and public sector credibility tend to attract more capital flows (Alonso Alvarez 2015). Finally, not only the conflicts but also their consequences have, in the form of external sanctions, a very negative effect on activity (Simola 2022, Borin et al. 2022, Mahlstein et al. 2022, Pestova et al. 2022)

In a recent paper (Diakonova et al. 2022b), we focus on the case of one country, Russia, and analyse the impact of policy uncertainty, conflict-related, and other shocks on economic activity. We choose Russia as it is a country with a long history of conflicts and shocks of any kind, from economic crises (e.g. sovereign defaults like the one in the summer of 1998) to armed conflicts, and as it is a systemic economy due to its role in energy and commodity markets and to its geopolitical relevance, as it has nuclear weapons and it is a permanent member of the UN Security Council. To proxy uncertainty we use the Economic Policy Uncertainty (EPU) indicator built up by Baker et al. (2016); we also include a set of indicators that refer to specific aspects of the concept of ‘conflict’: the geopolitical risk index (Caldara and Iacoviello 2022), the reported social unrest index (RSUI) from Barrett et al. (2020), and the conflict models of Mueller and Rauh (2022).

These indicators have been demonstrated to affect unemployment and stock prices, manufacturing and services production, economic growth and financial variables, and capital flows (Hadzi-Vaskov et al. 2021, Diakonova et al. 2022a, Ghirelli et al. 2019).

Russia and its long history of conflicts and shocks

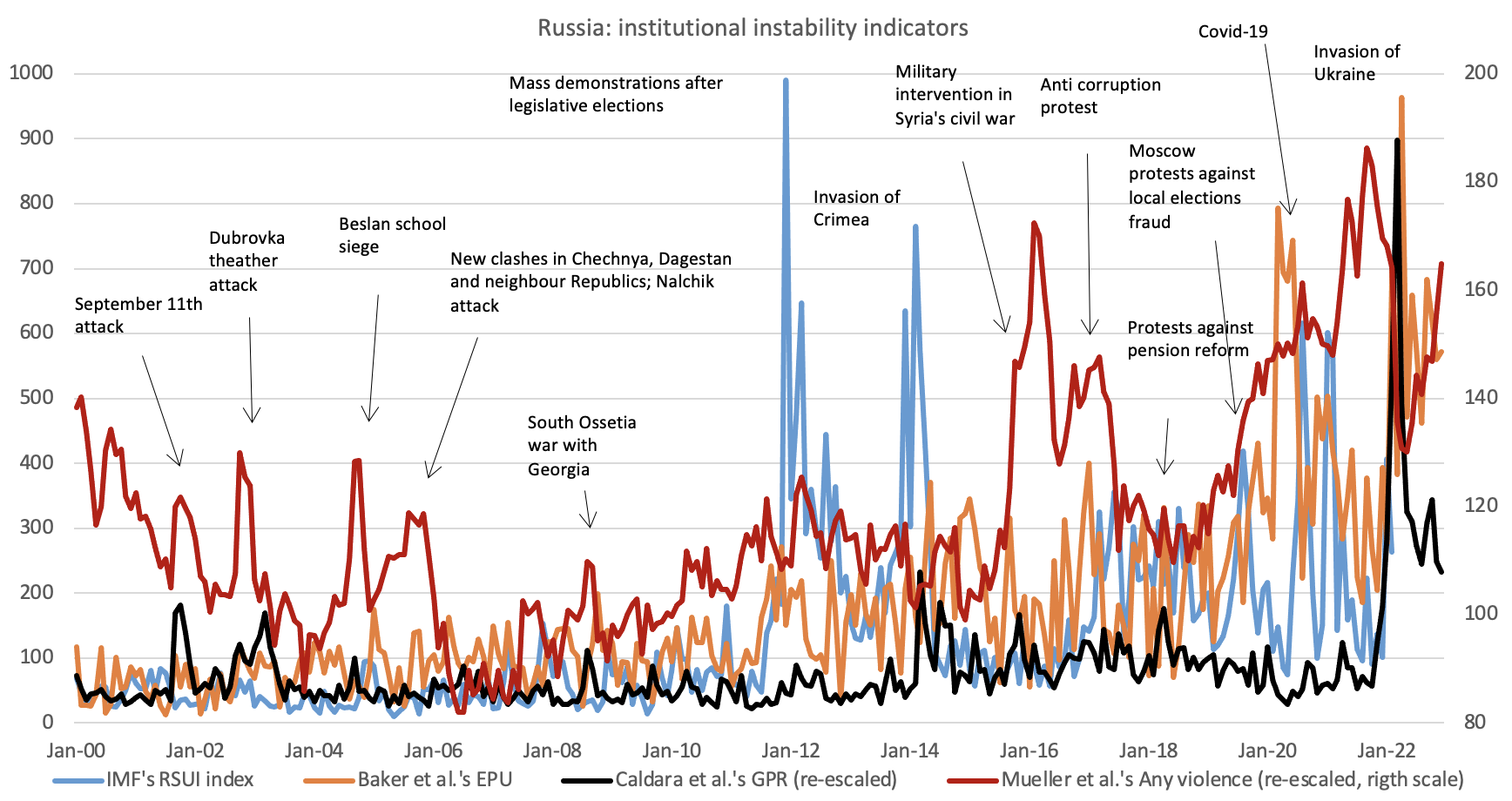

Russia has a long history of conflicts and diverse shocks. As seen in Figure 1, these conflicts and shocks had been very frequent and related to economic issues, internal protests, or open armed conflicts within Russian borders or with its neighbours. Note also that conflicts and uncertainty indicators (what we refer to in the figure as institutional instability indicators) have an increasing trend over time. This confirms the fact that institutional instability in this country has gained importance in the last years.

Figure 1 Indicators of policy uncertainty, geopolitical risk, social unrest, and armed conflict for Russia, 2000-2022

Source: Own calculations from Diakonova et al. (2022b).

At a bird’s eye view, the frequent blown up of conflicts and the sustained increase in instability indicators has affected Russian economic activity, as shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2 Selected institutional instability events versus GDP growth

Source: Diakonova et al. (2022b).

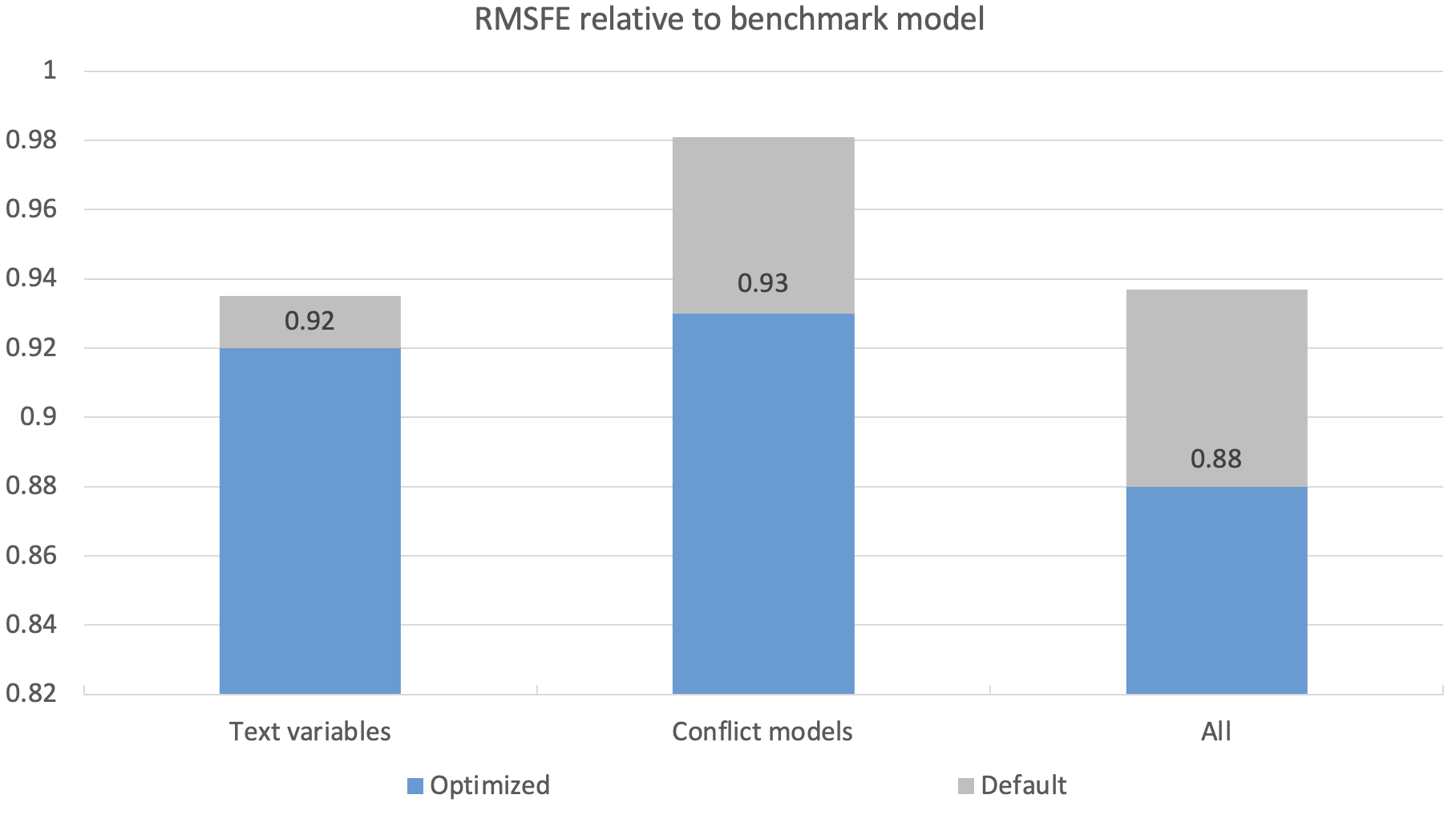

Conflict and uncertainty indicators improve the accuracy of Russian GDP forecasting

To test the influence of conflict and other kind of shocks on Russian economic activity we first quantify the gains made in forecasting Russian quarterly GDP by adding the Economic Policy Uncertainty index and conflict-type indicators to a broad standard set of monthly macroeconomic indicators usually introduced in standard nowcasting models. This includes variables like the industrial production, consumer confidence, sovereign rating, and sovereign spreads, oil production, and so on. Using a mixed-data sampling (MIDAS) framework in pseudo real time – so that different regressors become available with different time lags depending on when in the quarter the forecast is being made – we obtain that the optimal model for predicting Russian GDP is the one that includes both indicators of conflict risk and text-based variables of institutional instability: adding these variables to the traditional macroeconomic set lowers the root mean square forecasting error (RMSFE) by 12%, on average (Figure 3). This result is statistically significant.

Figure 3 Improvement in Russian GDP forecasting when introducing institutional instability indicators

Source: Diakonova et al. (2022b).

Conflict and economic policy uncertainty reduces Russian growth and increases the country risk premia

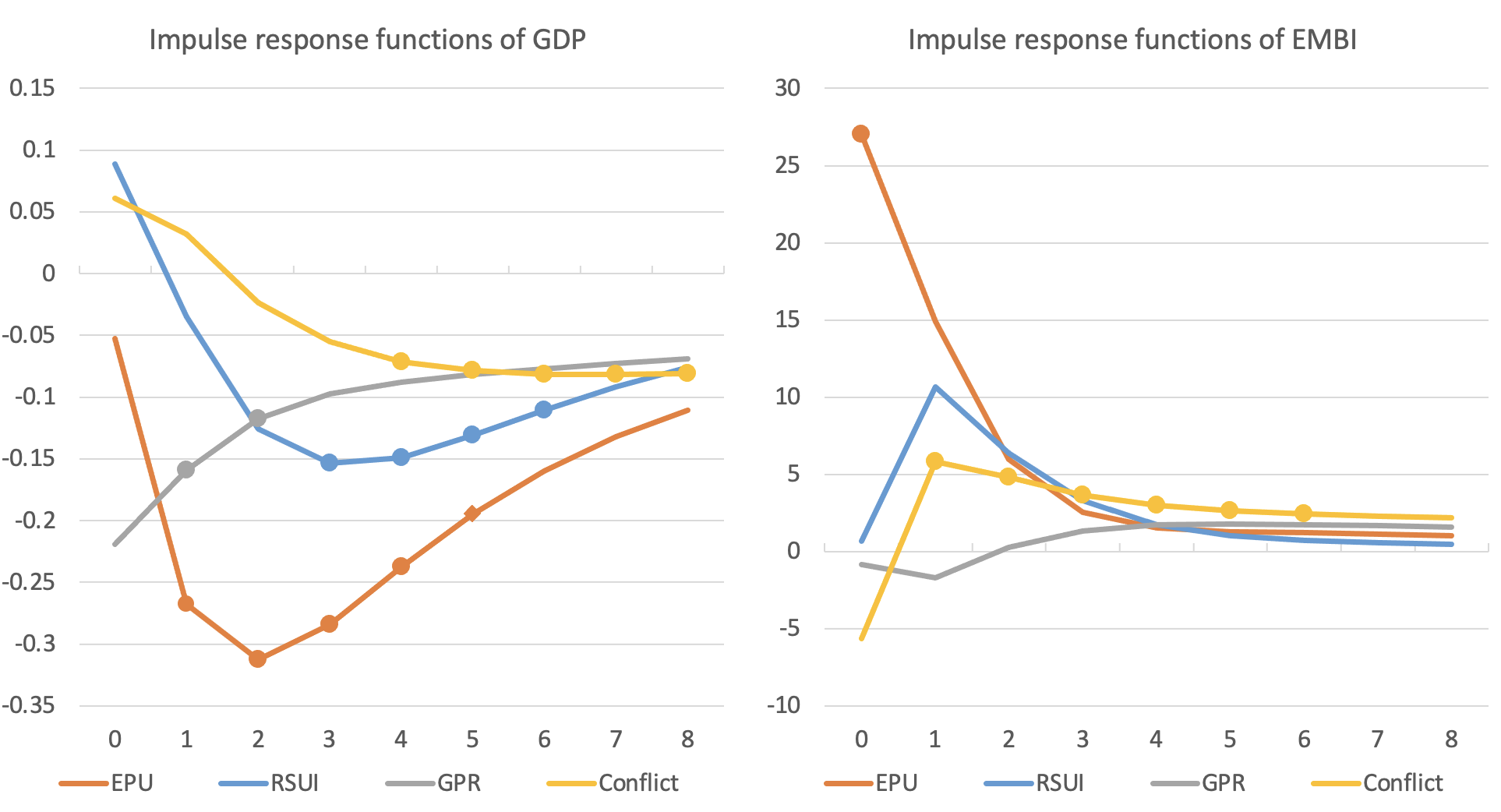

Do the conflicts and related shocks affect the main Russian economic variables? Our answer is yes, they do, and in a strong and persistent way. To come up with this answer we estimate a structural vector autoregressive (SVAR) model for the period 2000Q3-2019Q4 representing the Russian economy and compute impulse responses to structural shocks to institutional instability indicators (see Figure 4). The model includes (in this order) (i) an institutional instability variable (in turn, the economic policy uncertainty index, the geopolitical risk index, the social unrest index RSUI, and the conflict index), (ii) the sovereign spread (Emerging Market Bonds Index (EMBI+), in changes), (iii) the GDP (seasonally adjusted quarter-on-quarter growth rates), (iv) the headline consumer price index (seasonally adjusted quarter-on-quarter growth rates) and the VIX, which is included as an exogenous variable to control for global uncertainty shocks. The identification of structural shocks is obtained by means of Cholesky identification scheme.

The shocks to the institutional instability indicators that we consider to compute the impulse responses are similar to some observed in the past: (i) for the economic policy uncertainty, an increase similar to that registered during the Global Crisis in 2008, (ii) for the Russian geopolitical risk index, a shock similar to the observed during the second Chechen war and Putin’s declaration of foreign affairs and security policy top priorities, after the Dubrovka Theatre hostage crisis (October 2002), (iii) in the case of the Russian social unrest index, the shock is equivalent to the 2014 Russo-Ukrainian war, e.g. the armed conflicts that occurred in April between the Armed Forces of Ukraine and Russian-backed separatists from the self-declared Donetsk and Luhansk Republics, and (iv) the shock to the conflict variable is equivalent to the Russo-Georgian war that took place in August 2008.

The results are intuitive: a rise in institutional instability of any kind induces a decline in GDP growth of around 0.3 percentage points, whereas the EMBI spread increases by 25 basis points. Moreover, the effects seem to be quite persistent, as GDP growth takes more than two years to revert to trend after the shock in institutional instability, whereas the EMBI reverts approximately within a year. All these results are robust to a change in the VAR order or lags, and to the estimation of them through local projections. Overall, our models based on alternative measures of institutional instability confirm the same story: high institutional instability in Russia yields economic slowdown, with a persistent drop in GDP growth and a short-lived but high magnitude increase in country risk.

Figure 4 Impulse response functions of GDP and sovereign spread to shocks to institutional instability

Source: Diakonova et al. (2022b). Filled markers indicates that the estimated value is significant at 5% level.

Conclusion: The economic costs of the recent armed conflict

Russia´s long history of conflicts, economic policy uncertainty, and other related shocks could lead, according to standard macroeconomic models, to a persistent decrease in GDP growth rates and an increase in the country risk premium, both of which dwarf the raising of funds for Russian government or firms in international markets. Therefore, the best model to predict Russian GDP should include some variable that reflects the institutional instability of the country. In this sense, the estimated cost of the recent war with Ukraine could amount, even not taking into account the Western sanctions, to a fall of 4.4 percentage points of GDP, a shock very similar to the one generated by the Covid-19 pandemic.

References

Alonso Alvarez, I (2015), “Institutional Drivers of Capital Flows”, Banco de España Working Paper No. 1531, 16 November.

Baker, S, N Bloom and S Davis (2016), “Measuring Economic Policy Uncertainty”, The Quarterly Journal of Economics 131(4): 1593–1636.

Barrett, P, M Appendino, K Nguyen and J de Leon Miranda (2020), “Measuring Social Unrest Using Media Reports”, Journal of Development Economics 158.

Besley, T and H Mueller (2012), “Estimating the Peace Dividend: The Impact of Violence on House Prices in Northern Ireland”, American Economic Review 102(2): 810–33.

Besley, T and H Mueller (2018), “Predation, Protection, and Productivity: A Firm-Level Perspective”, American Economic Journal: Macroeconomics 10(2): 184–221.

Bloom, N (2009), “The impact of uncertainty shocks”, Econometrica 77(3): 623–685.

Borin, A, F Conteduca and M Mancini (2022), “The impact of the war on Russian imports: A counterfactual analysis”, VoxEU.org, 9 November.

Caldara, D and M Iacoviello (2022), “Measuring Geopolitical Risk”, American Economic Review 112: 1194–225.

Diakonova, M, L Molina, H F Mueller, J J Perez and C Rauh (2022a), “The Information Content of Conflict, Social Unrest and Policy Uncertainty Measures for Macroeconomic Forecasting”, Banco de Espana Working Paper No. 2232, 6 October.

Diakonova, M, C Ghirelli, L Molina and J J Perez (2022b), “The economic impact of conflict-related and policy uncertainty shocks: the case of Russia”, International Economics 174: 69-90.

Ghirelli, C, J J Pérez and A Urtasun (2019), “A new economic policy uncertainty index for Spain”, Economics Letters 182: 64-67.

Hassan, T A, S Hollander, L van Lent and A Tahoun (2019), “Firm-Level Political Risk: Measurement and Effects”, The Quarterly Journal of Economics 134(4): 2135–2202.

Hadzi-Vaskov, M, S Pienknagura and L A Ricci (2021), “The Macroeconomic Impact of Social Unrest”, Working Paper 2021/135; IMF.

Johnson, S, J McMillan and C Woodruff (2002), “Property Rights and Finance”, American Economic Review 92(5): 1335–56.

Mahlstein, K, C McDaniel, S Schropp and M Tsigas (2022), “Potential economic effects of sanctions on Russia: An Allied trade embargo”, VoxEU.org, 6 May.

Mueller, H and C Rauh (2018), “Reading between the lines: Prediction of political violence using newspaper text”, American Political Science Review 112(2): 358–75.

Mueller, H and C Rauh (2022), “The Hard Problem of Prediction for Conflict Prevention”, Journal of the European Economic Association 20(6): 2440-2467.

Pestova, A, M Mamonov and S Ongena (2022), “The price of war: Macroeconomic effects of the 2022 sanctions on Russia”, VoxEU.org, 15 April.

Simola, H (2022), “War and sanctions: Effects on the Russian economy”, VoxEU.org, 15 December.

Zussman, A and N Zussman (2006), “Assassinations: Evaluating the Effectiveness of an Israeli Counterterrorism Policy Using Stock Market Data”, Journal of Economic Perspectives 20(2): 193–206.