Judgements of the contributions of economists to the scientific literature, and their professional reputations, are influenced by both the number of times they publish and the perceived quality of the journals in which their publications appear. These judgements usually play an important role in hiring, promotion, and tenure decisions in research universities and many other institutions (Grimes and Register 1997, Combes et al. 2008, Conley et al. 2011).

The presence of well-recognised and prestigious journals on an author’s publication list clearly has a favourable impact on that author’s reputation, but much less is known about – and very little attention has been given to – the impact of publications in lower-ranked journals. Although these publications may have a positive social value in disseminating useful innovations and empirical findings, we do not know if this contribution is commensurately recognised in the judgements of other economists, and of those making decisions that affect the authors. It is not even clear if publications in lower-ranked journals, when added to publications in higher-ranked journals, have a positive or negative impact on other people’s assessments of the author.

The evidence that additional publications may not contribute much to reputation, and might even detract from it, comes from experiments that demonstrate the ‘less is better effect’, which is a focal illusion by which people in some contexts compare the value of two related goods, and assess the one with higher objective value as being worth less. For example, Hsee (1998) found that one group were willing to pay more for a 24-piece set of dinnerware in good condition than a similar group were willing to pay for a set that contained 28 (that is, four more) pieces in good condition, but included another 11 that were broken. The second set had more usable pieces, so objectively is was worth more, but was valued less. A third group were shown both sets, and they gave a higher value to the second set.

Average quality versus total productivity

In a new study, we attempt to understand if this effect was also true for academic output (Powdthavee et al. 2017). We ask if the inclusion of publications in well-known, respected, but lower-ranked journals alongside those in higher-ranked ones might not add positive impact to the assessments of other economists – or might even have a negative impact.

We sent out 1,827 email invitations to faculty members of 44 universities around the world (14 universities in the UK, 12 in the US, two in Canada, five in Continental Europe, one in Hong Kong, three in Singapore, six in Australia, and one in New Zealand) to take part in a survey. We also sent out email invitations to PhD students from seven universities in the US, the UK, Australia, and Singapore. We also invited 502 PhD students. We did not incentivise our colleagues to complete the survey, and we did not send reminders when questionnaires were not completed. We relied completely on their willingness to volunteer a few minutes of their time to participate in the survey, with only the promise that we would send them the results later if they were interested in having them. In total, we received 378 anonymous positive responses to our surveys, of which 52 were PhD students. This was a 16% response rate.

For every university in our list, we randomly allocated one of five different hypothetical publication lists for faculty members to rate. To find respondent valuations of the publication lists, we asked the following question:

“Without any other information, rate individual A’s publications as contributions to the literature and individual A’s professional reputation on the following 10-point scale, where 1 = worst possible CV, ... 10 = best possible CV”.

For the publication lists we provided, the first four were the primary tests of the influence of lower-ranked journals on economists’ judgements of publication lists. Two of them had two publications in ‘top five’ journals (Quarterly Journal of Economics and Journal of Political Economy), but each one added publications in lower-ranked journals, called ‘Long top 5’ and ‘Short top 5’, respectively (Table 1). The other two provided a similar comparison test, with and without lower-rated journals. In this case, both lists had no top five journals (‘Long no top 5’ and ‘Short no top 5’).

Table 1 Short versus long top 5 publication lists

Two further treatments asked for ratings of the same lists when each pair was viewed together by respondents – joint valuation of ‘Short top 5’ and ‘Long top 5’, and joint valuation of ‘Short no top 5’ and ‘Long no top 5’. The seventh treatment contained only lower-ranked journals (‘Long lower ranked’) and provided a confirmation test of the sensitivity of people’s judgements of the quality of publication lists to the rankings of the journals that are included.

Evidence from survey experiments

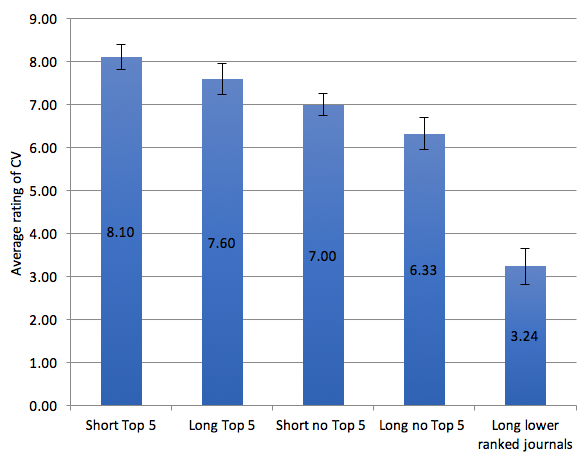

Figure 1, which reports the means of the single valuation ratings of the five lists, shows that the inclusion of low-ranked journals has a statistically significant negative impact on how other economists judge the value of the author’s contribution.

Figure 1 Ratings of different hypothetical CVs: Separate-evaluation treatments

Note: 95% confidence intervals (four-standard-error bars, two above and two below).

More specifically, respondents given the ‘Short top 5’ list gave it an average rating of 8.1, while those given the ‘Long top 5’ list provided ratings with a 7.6 mean. The mean rating given by respondents seeing only the ‘Short No Top 5’ list of journals – in which The QJE and JPE were replaced by two middle-tier general journals, Economica and Economic Inquiry – was 7.0. The mean rating given by economists shown only the ‘Long no top 5’ list was 6.3. Not surprisingly, the lowest single-valuation ratings were given to the list included as a consistency check, comprised entirely of publications in unambiguously lower-ranked journals (the ‘Long lower ranked’ list).1

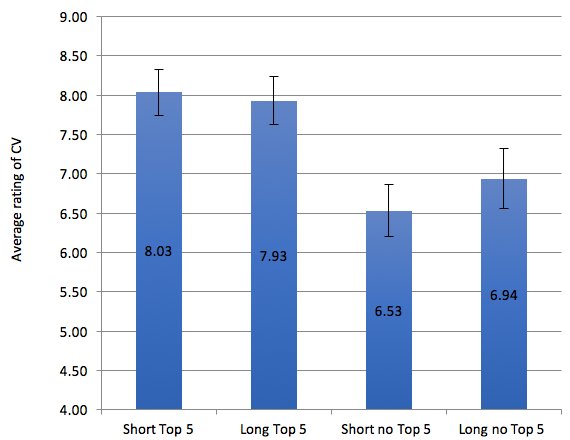

When judgements were based on examinations on isolated publication lists, adding publications in lower-ranked journals had a clear negative impact. The results were very different when respondents could do a simultaneous examination of both lists. Figure 2 reports the means of the joint valuation ratings of two pairs of publication lists. In this case, respondents could directly compare both lists, and could immediately see that the long list contained all of the journals in the short list, plus others. There was no negative impact from adding low-ranked journals in either test.

Figure 2 Ratings of different hypothetical CVs: Joint-evaluation treatments

Note: 95% confidence intervals (four-standard-error bars, two above and two below).

A less-is-better effect for publications

Our survey of judgements of the contributions of individual economists suggests this effect may compromise social efficiency and community welfare. These judgements could motivate individuals to withhold socially valuable research findings from publication rather than risk having it detract from their professional reputations. People would then be denied the benefits yielded by resources that have been expended to obtain them.

A further consequence induced by the way reputational and contribution judgements are made is that hiring and promotion committees and research granting bodies will receive somewhat distorted views of the social productivity of individuals. That this may well often occur receives some considerable credence from our finding that when people viewed both publication lists together, they valued the one with lower-ranked publications included as high or higher, so that the pattern that our findings suggest is likely to occur in the world – of giving negative value to lesser journal publications – will give a distorted view of the social value of the contributions of individuals. This can lead to distorted signals to committees and granting bodies, which, of course, can only undermine efficient allocations.

References

Combes, P-P, L Linnemer, and M Visser (2008), “Publish or Peer-Rich? The Role of Skills and Networks in Hiring Economics Professors”, Labour Economics 15(3): 423-441.

Conley, J P, M J Crucini, R A Driskill, and A Sina Önder (2013), “The Effects of Publication Lags on Life‐Cycle Research Productivity in Economics”, Economic Inquiry 51(2): 1251-1276.

Grimes, P W, and C A Register (1997), “Career Publications and Academic Job Rank: Evidence from the Class of 1968”, Journal of Economic Education 28(1): 82-92.

Hsee, C K (1998), “The Evaluability Hypothesis: An Explanation of Preference Reversals Between Joint and Separate Evaluation of Alternatives”, Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes (46): 247-257.

Powdthavee, N, Y E Riyanto and J L Knetsch (2017), “Impact of Lower Rated Journals on Economists’ Judgements of Publication Lists: Evidence from a Survey Experiment”, IZA Discussion Paper No. 10752.

Endnotes

[1] The Mann-Whitney test indicated a comfortable level of statistical significance between each pair of means. The differences in the mean values continue to be statistically significant when we held constant other potential confounding influences