The Cassandras who warned of a looming manufacturing collapse and an energy crisis in the wake of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine mostly got it wrong. The energy shock did materialise and was unprecedented in terms of both prices and quantities. In France, for example, where energy subsidies were concentrated on households and very small firms, the price shock was massive for manufacturing firms. INSEE, the French national statistical institute, reports that in 2022 electricity and gas prices for manufacturing firms increased by 45% and 107%, respectively. Recent data released by Eurostat also show a substantial redirection of gas flows: before the war, EU natural gas imports from Russia made up almost 50% of the total; this fell significantly to around 14% today.

However, the massive shock on gas and electricity did not cause the sharp drop in industrial production that was feared in Europe. In France, manufacturing production actually increased by 2.6% in 2022. At the same time, energy-intensive manufacturing firms reduced their electricity demand by 22%.

This suggests that firms found ways to adjust not primarily through reductions in output, but through other channels which one can refer to as substitutions. This was the message of Bachmann et al. (2022) in an early and ex-ante analysis, controversial at the time, of the channels through which the German economy could adjust and adapt to an embargo on Russian energy. The analysis was extended to Europe by Baqaee et al. (2022). An ex-post analysis by Moll et al. (2023) also concludes that the manufacturing sectors in Europe managed the shock.

How did they do it? We do not yet have firm- and plant-level data to precisely document the microeconomic mechanisms of adjustment during the crisis. But we can learn from past episodes of energy price hikes. This is what we do in a recent paper (Fontagné et al. 2023), where we mobilise plant- and firm-level data over a long period (1996–2019). Our granular approach sheds a precise light on the many channels of adjustments that manufacturing firms make in the face of energy price hikes.

Combining the annual survey on energy consumption conducted at the plant level in France with balance sheets and custom data, we are able to estimate the effect of gas and electricity price shocks on firm-level energy demand, efficiency, prices, exports, employment, production, and profits of French firms for the period 1996–2019.

One limitation of our analysis in understanding the present crisis is that idiosyncratic firm-level shocks before 2022 may not be similar to the aggregate shock experienced in Europe in 2022. Indeed, past channels of adjustment may not be identical, qualitatively and quantitatively, to those of 2022. However, our firm-level elasticities produce estimates that are broadly consistent with the aggregate impact of energy price shocks observed in 2022. This suggests that the firm-level channels of adjustments we quantify for past energy shocks may also be at work in the 2022 crisis.

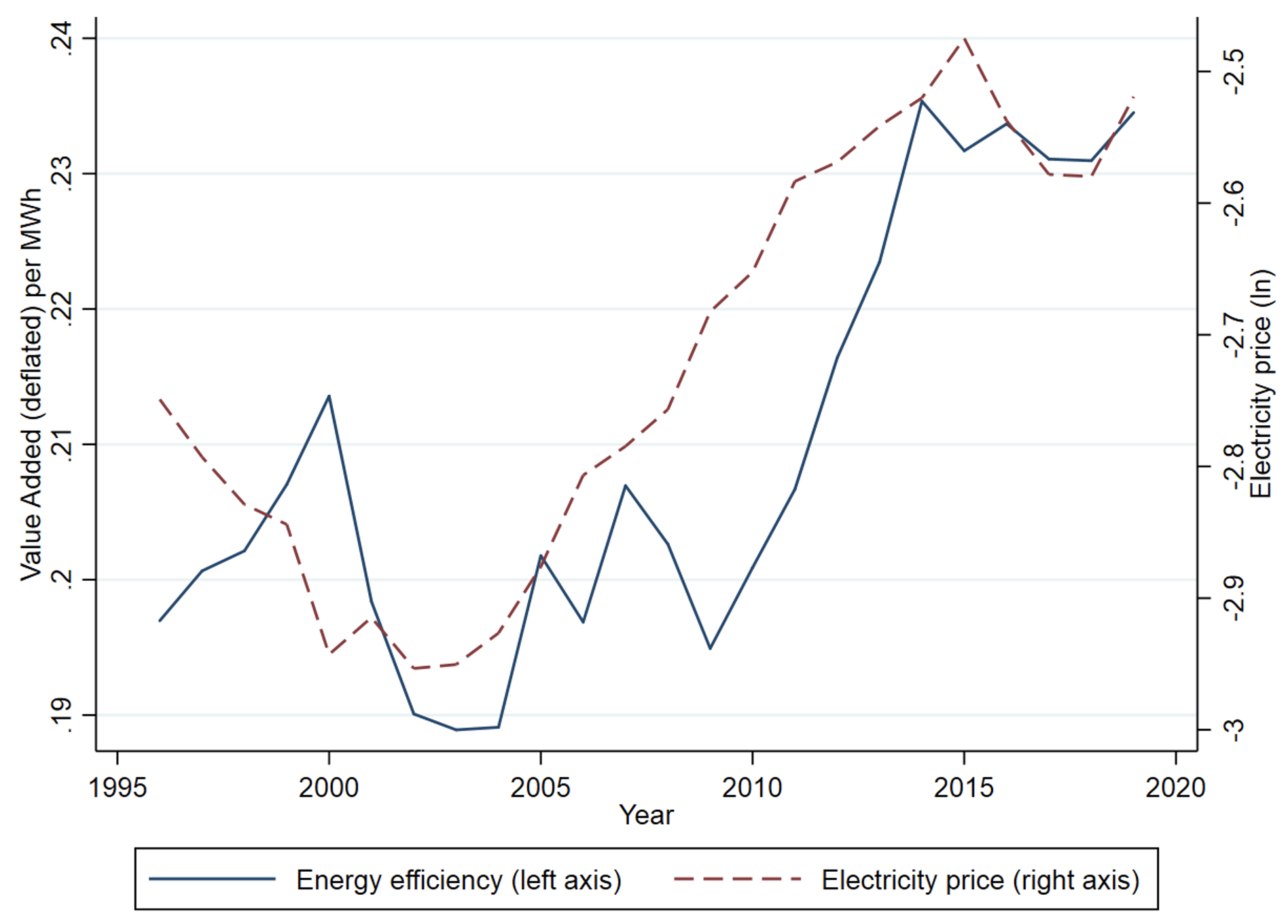

The mechanisms of adjustment that we identify based on data before the 2022 crisis are also consistent with anecdotal evidence reported in the media and survey data after the crisis. For instance, INSEE documents that French manufacturing firms, faced with the energy shock, adapted their production methods (38%) and invested to reduce or optimised their consumption (29%). This channel of adjustment – energy efficiency – is visible in Figure 1, where we plot the average electricity price and energy efficiency of French firms, calculated as the ratio between the export-price-deflated value-added of the firms and the energy consumption.

During 1996–2019, electricity prices paid by French firms and energy efficiency appear to be strongly correlated. Our analysis confirms that the positive impact of energy shocks on energy efficiency is also at work at the firm level.

Figure 1 Energy efficiency and electricity price

Source: EACEI and FICUS/FARE data

We first show that firms adjust to an energy price shock by reducing energy demand. Our preferred (and conservative) estimates of the average demand elasticity at the firm level are around -0.4 for electricity and -0.9 for gas. Only a small share of the fall in energy demand comes from a fall in production, consistently with the observed resilience of the manufacturing sector. For the largest price shocks (a yearly increase of more than 36% for electricity and 53% for gas), we observe that demand elasticities are – similar to those experienced in 2022 – smaller (but still significant) and equal to -0.2 for electricity and -0.7 for gas. Interestingly also, the price elasticity of energy demand has fallen over time as a result of increasing energy efficiency.

A second result is that manufacturing firms pass through fully, or even more, the impact of energy-cost shocks into their (export) prices, as also observed by Joussier-Lafrogne et al. (2023). This in turn reduces their competitiveness and entails a fall in demand for their products. The fall in exports is consistent with an international price elasticity of around 5, which we reported in previous work (Fontagné et al. 2018).

When one controls for the bilateral (France to destination country) real exchange rate, the impact of an energy shock is large: a 10% increase in electricity prices reduces export quantities by around 2%; a 10% increase in gas prices reduces exports by around 1%. It suggests that to compensate for the competitiveness loss due to the electricity price shock, a 7% (or 3% for gas) bilateral depreciation of the euro would be necessary. In the present crisis, although the euro has depreciated in real effective terms (around 3% relative to the 2019–2021 period, according to the ECB in 2022), this has not compensated for the loss in competitiveness due to the energy price shock.

The energy price shock also generates a fall in production and employment: a 10% increase in electricity price translates into a 1.6% fall in production and a 1.5% fall in employment. Energy efficiency increases at the firm level. Profits fall but modestly or only for the most-gas-intensive firms. However, these negative impacts wane over time. Our interpretation is that during 1995–2019, firms adapted their technology and production processes to higher energy prices and a selection process eliminated those not able to adjust.

All in all, these results suggest that firms are able to adjust and adapt strongly to energy shocks but that the competitiveness impact is significant and must be taken into account in the European energy policy.

Another channel that we uncover (and that was discussed anecdotally in the press in the present crisis) is that, on top of the channels already mentioned, multi-plant firms relocate energy demand (and presumably production) towards plants with lower prices and increase imports of intermediate inputs (presumably those inputs that are more energy intensive).

Finally, we uncover another channel of adjustment to an energy price shock. Firms can alter their production process to substitute imported inputs (presumably those most intensive in energy) with locally produced inputs. We observe that for electricity price shocks, firms do increase the imports of intermediate inputs, which may be a better measure of the substitution towards sources of production with lower energy prices.

What implications can we draw from these findings in terms of economic policy? Some governments in Europe have adopted policies aiming to reduce the energy price shock for manufacturing firms and are considering potential energy subsidies for future shocks. This is a costly option that would contradict our climate objectives. Given the observed ability of firms to adapt to energy price shocks through increased energy efficiency – and also the importance of cheap energy for manufacturing competitiveness, which we document – our results suggest that public money would be better used to help firms transition to cleaner and cheaper energy and to technologies that are less dependent on imports.

References

Bachmann, R, D Baqaee, C Bayer, M Kuhn, A Löschel, B Moll, A Peichl, K Pittel, and M Schularick (2022), “What if? The economic effects for Germany of a stop of energy imports from Russia”, ECONtribute Policy Brief 28.

Baqaee, D, B Moll, C Landais, and P Martin (2022), “The economic consequences of a stop of energy imports from Russia”, Focus 84.

Fontagné, L, P Martin, and G Orefice (2018), “The international elasticity puzzle is worse than you think”, Journal of International Economics 115: 115–29.

Fontagné, L, P Martin, and G Orefice (2023), “The many channels of firm’s adjustment to energy shocks: Evidence from France”, CEPR Discussion Paper 18262.

Joussier-Lafrogne, R L, J Martin, and I Méjean (2023), “Cost pass-through and the rise of inflation”, mimeo, Sciences Po.

Moll, B, M Schularick, and G Zachmann (2023), “Not even a recession: The great German gas debate in retrospect”, ECONtribute Policy Brief 48.